Are Psychiatrists Cost-Effective? An Analysis of Integrated Versus Split Treatment

Abstract

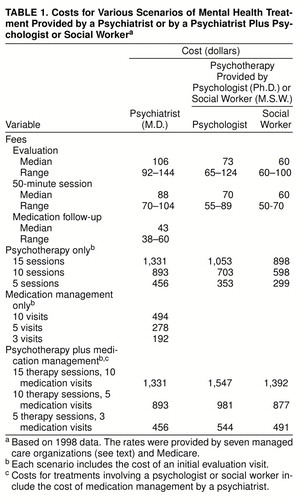

OBJECTIVE: Managed care organizations prefer putatively less expensive split treatment, i.e., a psychopharmacologist plus a non-M.D. psychotherapist. In this study the cost of integrated care by a psychiatrist was compared with split care. METHOD: Using 1998 fee schedules of seven large managed care organizations (with 54.3% market share and 67.8 million lives) plus Medicare (37 million people), the author modeled clinical scenarios of psychotherapy alone, medication alone, and combined treatment provided by a psychiatrist or split with a psychologist or social worker. RESULTS: Brief psychotherapy by a social worker was the least expensive treatment. When treatment required both psychotherapy and medication, combined treatment by a psychiatrist cost about the same or less than split treatment with a social worker psychotherapist; it was usually less expensive than split treatment with a psychologist psychotherapist. CONCLUSIONS: The integrated biopsychosocial model practiced by psychiatry is both theoretically and economically the preferred model when combined treatment is needed.

Recently, medicine and managed care organizations have embraced the primary care model, with its increased emphasis on psychological factors, behavioral health, and lifestyle issues and its belief that this biopsychosocial treatment should be provided by a single physician as opposed to the fragmented care received in the past from several specialists. In contrast, the only mental health practitioner who can provide comprehensive biopsychosocial care, i.e., the psychiatrist, is being replaced by fragmented care (psychotherapist-psychopharmacologist split).

It has been reiterated that the driving force behind managed care and health care reform is cost, cost, and cost. To reduce costs, patients who require psychotherapy and medication combined are preferentially assigned to split treatment. Also, psychiatrists are often replaced with family doctors, who are less expensive but miss diagnoses, undertreat with low doses and short time periods, and do not offer psychotherapy (1, 2). Poor treatment has its economic and human misery costs (3), and therefore, this option will not be considered further in this analysis.

The theory and practice of optimal psychiatric care militate against the split treatment model, but is it less expensive than integrated care? This question was tested by using data from current managed care schedules.

METHOD

I collected 1998 payment schedules (received unsolicited or by direct request) from seven large managed care organizations with a combined 1996 market share of 54.3% and 67.8 million lives. These organizations, and their respective 1996 ranks, market shares, and numbers of lives covered, are as follows (4): Value Behavioral Health (1, 19.4%, 24.2 million), Merit Behavioral Care (3, 12.2%, 15.3 million), Green Spring Health Services (4, 10.0%, 12.4 million), U.S. Behavioral Health (6, 5.0%, 6.2 million), MCC Managed Behavioral Care (8, 4.1%, 5.2 million), Options Health Care (11, 2.2%, 2.7 million), and CMG Health (15, 1.4%, 1.8 million). Medicare, which covered another 36.9 million lives in 1996, was also included. Based on median rates, the costs for the following treatment scenarios were calculated.

| 1. | Five, 10, and 15 psychotherapy sessions (initial evaluation plus 50-minute sessions) with a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | Three, five, and 10 medication visits (initial evaluation plus 20-minute visits) with a psychiatrist. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Psychotherapy and medication provided by a psychiatrist (integrated) or split between a psychiatrist and psychologist or social worker, as follows

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

RESULTS

The results are presented in table 1.

DISCUSSION

When both medication and psychotherapy are indicated, a patient is best and most cost-effectively served by a psychiatrist providing both treatment modalities. For instance, compared to $981 for split treatment by a psychiatrist plus psychologist (five medication visits and 10 psychotherapy sessions), it costs $893 (or $88 less) for a psychiatrist integrating the two modalities. In addition, with the psychiatrist the patient makes only 10 “doctor visits” (versus 15 in split treatment), has to deal with only one person (versus two), has medication monitored at each of the 10 visits (versus five), and pays $88 less. All of these advantages hold true in the comparison with split treatment involving a social worker therapist, for which the additional cost over integrated treatment is $16. When time away from work or child care plus the expense and time of traveling are factored in, the cost-benefit analysis favors integrated care from a psychiatrist even more.

For patients who require more intensive treatment, integrated care by a psychiatrist remains economically advantageous. Fifteen psychiatrist visits for integrated care cost $1,331, compared to $1,547 for split treatment with a psychologist or $1,392 for a social worker, both of which are higher, by $216 and $61, respectively.

A recent study (5) of one managed care organization supports these findings. Of 1,517 depressed patients followed over 18 months, those “receiving integrated treatment used significantly fewer outpatient sessions and had significantly lower treatment costs” than patients in split treatment ($1,336 versus $1,854).

Sparsely monitored medication management (three or five visits) was the least expensive modality ($192 and $278, respectively) and is increasingly favored by managed care organizations (6) . However, when medication costs (for example, approximately $720 per year for the newer antidepressants) are added in, treatment with medication alone becomes more expensive than short-term psychotherapy alone by a social worker ($299 for five sessions, $598 for 10 sessions).

Further research is required to differentiate a priori the patients who will respond to brief psychotherapy alone versus combined treatment. For instance, Thase et al. (7) suggested that depressed patients with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores over 20 did better with medication than either cognitive or interpersonal therapy. Such patients should be referred to a psychiatrist for antidepressant therapy with optional adjunctive psychotherapy. However, managed care organizations preferentially refer all patients to nonpsychiatrist therapists first, with the option of a medication evaluation later (5). This may delay effective treatment. In clinical practice, although guidelines suggest that depressed patients not responding adequately to psychotherapy within 3 months should be referred for medication evaluation (8), one study (9) showed that this referral actually took place after 6–14 months.

The data in this study suggest that the split model currently promoted by managed care organizations and health maintenance organizations and projected as the future of psychiatry is theoretically and economically unsound. However, this narrow definition of a psychiatrist, i.e., one who prescribes psychotropic medication in 15-minute blocks and does no psychotherapy, has been widely accepted and used to estimate future manpower needs (10, 11). Estimates should be revised with the assumption that psychiatrists provide psychotherapy as a part of integrated treatment to large numbers of seriously ill patients, which is precisely what is occurring today (6).

Acceptance of the integrated model as the future of psychiatric practice would also require residency training programs to continue teaching psychotherapy, with a new focus on the time-effective, cost-effective specific forms (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy).

Payment schedules vary by year, region, managed care organization, and even plans within a managed care organization. The small group of 1998 rates in central New York used in this study is therefore merely illustrative. Further, the treatment scenarios used were arbitrary in their mix of number and type of sessions, but I attempted to reflect reasonable current treatment patterns. Studies of randomized assignment to integrated or split treatment with quantitative data on treatment effectiveness and cost-efficiency are needed. If findings of such studies supported the cost-effectiveness of integrated treatment, psychiatry could vigorously advocate the integrated biopsychosocial model on both theoretical and economic grounds.

Presented at the 150th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Diego, May 17–21, 1997; Received Nov. 19, 1997; revision received July 17, 1998; accepted Aug. 25, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York Health Sciences Center at Syracuse. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dewan, Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York Health Sciences Center, 750 East Adams St., Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

1. Schulberg H, Block M, Madonia M, Scott C, Rodriquez E, Imber S, Perel J, Lave J, Houck P, Coulehan J: Treating major depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:913–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care 1992; 30:67–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells K, Stewart A, Hays R, Burnam M, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Managed behavioral health market share rankings: Value Behavioral Health has largest enrollment among managed behavioral health organizations in 1996. Open Minds 1996; 10(6):9Google Scholar

5. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Cuffel B, Zarin D, Suarez A, Burns B: Outpatient utilization patterns of integrated and split psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49:477–482Link, Google Scholar

6. West J, Zarin D, Pincus H: Clinical and psychopharmacologic practice patterns of psychiatrists in routine practice. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:79–85Medline, Google Scholar

7. Thase M, Greenhouse J, Frank E: Correlates of remission of major depression during standardized trials of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or their combination. Psychopharmacol Bull (in press)Google Scholar

8. Depression Guideline Panel, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Depression in Primary Care. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

9. Kendall P, Kipnis D, Otto-Salaj L: When clients don’t progress: influences on and explanations for lack of therapeutic progress. Cognitive Therapy and Res 1992; 16:269–281Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Weiner J: Forecasting the effects of health reform on US physician workforce requirement: evidence from HMO staffing patterns. JAMA 1994; 272:222–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weissman S: Recruitment and workforce issues in late 20th century American psychiatry. Psychiatr Q 1996; 67:125–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar