Affective Responsiveness in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Psychophysiological Approach

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of the study was to investigate affective responses to emotional stimuli in subjects with borderline personality disorder. METHOD: Twenty-four female patients with borderline personality disorder and 27 normal female comparison subjects were examined. The test stimuli were a set of standardized photographic slides with pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant emotional valence. In addition to self-reports, emotional reactions to the slides were measured by heart rate, skin conductance, and startle response. Psychometric tests for various aspects of impulsiveness were also completed. RESULTS: Neither self-report nor physiological data gave any evidence that the borderline patients showed more intense affective responses than did the normal subjects. The borderline subjects did not produce higher levels of startle amplitude, and while viewing unpleasant slides, they showed a startle potentiation effect that was largely similar to that of the comparison group. In fact, the borderline patients showed low electrodermal responses to all three stimulus categories, which points to physiological underarousal. CONCLUSIONS: The results do not agree with the hypothesis that there is a fundamental, biologically based affective hyperresponsiveness in borderline personality disorder, as is suggested by current theories of affect dysregulation in the disorder. Autonomic underarousal may seriously interfere with a flexible adaptation to environmental stimuli.

Affect dysregulation is considered a hallmark of borderline personality disorder. According to Linehan’s concept of the disorder (1), affective vulnerability stems from affective hyperarousal, including a high sensitivity to emotional stimuli and high emotional intensity. (The words “affect” and “emotion” are used synonymously.) Affective hyperarousal is thought to be of high clinical significance because it leads to marked, rapidly changing mood states and predisposes patients to various kinds of impulsive self-destructive behaviors, which are used as maladaptive mechanisms for relieving intense, unbearable negative affect (1). The theory of affect dysregulation, derived from clinical observation, was recently confirmed in an experiment using emotional stimuli related to borderline personality disorder subjects’ pathognomonic fear of being abandoned (2). So far, there has been hardly any systematic study of emotional responsiveness in subjects with borderline personality disorder, and the few studies there are were based almost exclusively on the patients’ own subjective reports of intense affect experiences.

To our knowledge, objective physiological correlates of emotion have not yet been investigated in borderline personality disorder. However, psychophysiological research has been essential for a pathogenetic understanding of psychopathy—in particular, findings of deficient autonomic responses to punishing or threatening situations, but also to nonsignal stimuli (3, 4). The low level of autonomic arousal shown by the electrodermal and cardiovascular response system has been interpreted essentially in two ways: either it can lead to stimulus seeking, since low arousal represents an aversive physiological state (5–7), or it can be seen as a marker of low fear levels, which would seriously interfere with the anticipation of danger (8). However, underarousal is regarded not only as a risk factor for developing aggressive behavior but also as predisposing toward a generally disinhibited temperament (8), a characteristic of antisocial as well as borderline subjects. Therefore, impulsive behavior may occur not only in hyperarousal but also in underarousal.

More recently, correlates of physiological affect other than visceral responses have been used. In particular, the blink response to a startling probe and its modulation by affective processes have increasingly met with interest (9). Studies on normal subjects have repeatedly shown that the magnitude of the blink response to a startling acoustic probe is greater when the subjects view slides presenting an unpleasant theme than when they view slides with a pleasant theme (10). This can be explained within a motivation priming paradigm by synergistic response matching: the amplitude of the blink reflex to the aversive startle probe is augmented in the context of an ongoing aversive affect and is inhibited in the context of stimuli imparting a positive affect (10). Some groups have studied the influence of personality on the intensity of the startle reflex. Cook et al. (11) reported greater emotional startle modulation among highly fearful personalities in comparison with personalities with low fear while they were viewing unpleasant slides, suggesting that an enhanced startle modulation is associated with an increased tendency to experience negative affective states. On the other hand, Patrick et al. (12) found that potentiated startle was absent in psychopathic individuals during exposure to unpleasant slides. This finding was more closely associated with emotional detachment than with disinhibited behavior.

Thus, some of the more important questions arising from theories about affective responsiveness in borderline personality disorder are as follows. 1) Do physiological indicators of emotional processing support the hypothesis of emotional hyperarousal in borderline personality disorder? 2) Do subjects with the disorder show intense emotional reactions only to specific stressors related to a personal context, or are they hyperresponsive to emotionally relevant stimuli in general? 3) In a clinical setting, negative affective shifts attract more attention than positive ones; however, do individuals with borderline personality disorder also show intense positive affect when reacting to pleasant stimuli? 4) Finally, the relationship between emotional responsiveness and impulsive behavioral problems needs to be further clarified.

It was the aim of this study, therefore, to assess the responses of subjects with borderline personality disorder to standardized stimuli on various affective response channels. In addition to filling out self-rating forms, the subjects underwent various psychophysiological tests related to the two basic emotional dimensions of valence (pleasure versus aversion) and arousal (activation versus calmness) (13). Skin conductance was included as a physiological arousal measure, and the eye-blink startle reflex elicited by the acoustic probe was used as a measure of valence (14). Startle response amplitude and latency, in particular, also reflect arousal, since affective modulation occurs only with highly arousing stimuli (9). Finally, changes in heart rate were recorded as an ancillary measure. Since heart rate is sensitive to changes in affective state as well as to task demands, unpleasant stimuli are often accompanied by a higher sensitivity to the environment and heart rate deceleration, unless (e.g., in the case of fear) they evoke a defensive reaction reflected by acceleration (15, 16).

Our hypothesis was that in comparison with normal subjects, subjects with borderline personality disorder would show more intense affective reactions to standardized slides with pleasant and unpleasant valence, as indicated by verbal-cognitive and physiological response measures. Furthermore, we hypothesized that intense emotional responses would correspond to an impulsive style of personality functioning, as assessed by personality questionnaires.

METHOD

The study subjects were 24 female patients with borderline personality disorder and a comparison group of 27 normal women. The clinical group was recruited from consecutively admitted patients who had attended an inpatient treatment program for severe personality disorders in a fixed time interval of 6–18 months before the investigation. This selection ensured that definite trait features of borderline personality disorder would be investigated rather than state conditions of serious affective disturbance. Only female subjects were chosen because gender may influence affective responses to specific stimuli. Borderline personality disorder was assessed according to the DSM-III-R criteria by two independent raters using the International Personality Disorder Examination (17). Interrater reliability for the borderline personality disorder diagnosis was 1.00, with corrected kappas ranging from 0.82 to 0.96 for individual items. In order to secure a homogeneous group of affectively unstable and impulsive borderline patients, we included only women with borderline personality disorder who met the criteria of affective instability (item 6) and impulsive behavior (item 4 and/or item 5). Individuals diagnosed with additional organic mental disorder, schizophrenia, paranoid disorder, or current drug or alcohol abuse were excluded from the study. Those with comorbid antisocial or histrionic personality disorder were also excluded because these disorders show overlapping features with borderline personality disorder. All potential subjects were screened for drugs that might confound physiological responses, such as antidepressants, anticholinergics, β blockers, and neuroleptics.

The comparison group was recruited through a bulletin board announcement; one-third were university students, one-third were nonacademic hospital staff members, and one-third were vocational school students. They had no lifetime history of psychiatric treatment, and, as assessed by the International Personality Disorder Examination, did not show any axis II disorder or dysfunctional impulsive behavior.

All subjects were tested psychometrically for impulsiveness, sensation seeking, and enduring aggressive behavior. Three self-rating tests were used: the tenth version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (18), the Sensation-Seeking Scale (6), and the questionnaire for the Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness (19). This last instrument is a German test modeled closely after the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (20).

The two groups were highly comparable in age and education. The ages of the subjects with borderline personality disorder ranged from 20 to 41 years (mean=28.0, SD=6.1), and the ages of the comparison subjects ranged from 19 to 41 years (mean=26.3, SD=6.4). Years of education ranged from 10 to 13, with a mean of 11.2 (SD=1.5) for the subjects with borderline personality disorder and a mean of 11.3 (SD=1.5) for the comparison subjects. All subjects were paid for participating in the study and gave written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Procedure

Each subject viewed a series of 18 color slides that were taken from a pool of standardized slides, the International Affective Picture System (21), which was developed to provide a set of normative emotional stimuli for experimental investigations (15). The subjects were seated comfortably in a separate laboratory room where the temperature and level of humidity were kept constant. Six pleasant slides (sport scenes, pets, and romantic couples), six unpleasant slides (wild animals attacking, aimed guns, and mutilated bodies), and six neutral slides (household objects) were shown for 6 seconds each. To avoid effects due to the order of presentation, the slides were presented in blocks of three—one pleasant, one neutral, one unpleasant—ordered randomly within each block. Matched subject pairs from the patient and comparison groups were shown slides in identical order. After each slide, subjective ratings of valence and arousal were made with the Self-Assessment Manikin (22).

Physiological measures of heart rate and skin conductance response were recorded by means of a modular system (ZAK Medical Technics, Marktheidenfeld, Germany), and the startle reflex by means of a commercial startle system (San Diego Instruments). Both were connected to a personal computer for processing data (software DIAdem, GfS, Inc., Aachen, Germany). All physiological signals were assessed according to general practice in psychophysiology (23). They were recorded with the use of Ag-AgCl electrodes of different sizes, filled with electrolyte paste. Impedances were kept below 5 kW. Autonomic base values (skin conductance level, heart rate) were taken over a 6-second time interval before the experiment was started.

Heart rate signals were recorded from the left forefinger by an infrared sensor. The signals were sampled at 50 Hz, rectified and integrated with a time constant of 0.3 second within a measuring range of 1 mV. Heart rate activity was defined as the mean change, during the first 3 seconds after slide onset, from the 3-second baseline mean immediately preceding slide onset. Skin conductance activity was measured from the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the nondominant hand, sampled at 50 Hz, rectified and integrated with a time constant of 0.3 second within a measuring range of 0–30 µS. Magnitude of the skin conductance response was defined as the largest increase standardized to the intraindividual maximum within 0.9 and 4 seconds after slide onset; values were logarithmically transformed. The acoustic startle probe we used was a 50-msec burst of white noise at 100 dB delivered binaurally over continuous 60-dB background noise. Three initial startle signals were given to counteract the habituation effect during the actual experiment. Afterward, startle probes were delivered randomly within 3–5 seconds after the beginning of 15 of the 18 slide presentations. A further three probes were delivered between trials to reduce predictability and to control for baseline startle responses (i.e., responses without preceding emotional stimuli). The eye-blink reflex was measured with electrodes positioned at the orbicularis oculi muscle underneath the left eye. Electromyogram activity was amplified by a factor of 10,000 with a 100- to 1000-Hz band-pass filter, digitized at 1 kHz, recorded in a 10- to 150-msec time window from the onset of the acoustic stimuli, rectified and stored for offline analysis.

Data Analyses

All variables were tested for normal distribution. One-third of them were not distributed normally. Therefore, all main effects of analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were controlled by using nonparametric statistical procedures. One-way ANOVAs were used to test group-specific effects of personality variables and psychophysiological base rates. To examine changes in physiological measures as a function of the affective valence of the stimuli in addition to group effects, repeated measures ANOVAs were used for the experimental data, with diagnostic group (borderline personality disorder, comparison) as a between-subjects factor and slide valence category (pleasant, neutral, unpleasant) as a within-subject factor. All analyses were two-tailed. In addition to tests for overall slide valence effects, post hoc pairwise comparisons of slide valence categories (pleasant-neutral, pleasant-unpleasant, neutral-unpleasant) were done; they included Bonferroni-Holm alpha error adjustment. If significant interactions between group and slide valence were found, group effects were additionally analyzed by post hoc pairwise comparisons, as well as by post hoc one-way ANOVAs for group differences in relation to each of the three slide valence categories. The level of significance was always set at p=0.05. If a main effect was observed for diagnosis with regard to scores on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, the Sensation-Seeking Scale, or the Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness, their influence on overall group differences in physiological data were analyzed by means of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

To correct for intraindividual outliers and to adjust for interindividual differences in startle response, a standardization procedure, similar to z score transformation, was performed. The raw scores of each subject were subtracted from her individual mean and divided by her standard deviation, converting raw scores to a distribution of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. This standardization procedure does not change response patterns for individual subjects (i.e., relative magnitudes of response to the three slide valence categories) but establishes a common metric between the subjects (16). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 6.12 (24).

RESULTS

One-way ANOVA results for the psychometric variables revealed significant group-specific effects for the personality traits of impulsiveness (for Barratt Impulsiveness Scale total score, F=12.94, df=1, 49, p=0.0008) and aggressiveness (for Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness sum score over the first three factors, F=38.25, df=1, 49, p=0.0001). However, ANOVAs did not reveal significant differences in sensation seeking (for Sensation-Seeking Scale total score, F=0.21, df=1, 49, p=0.65).

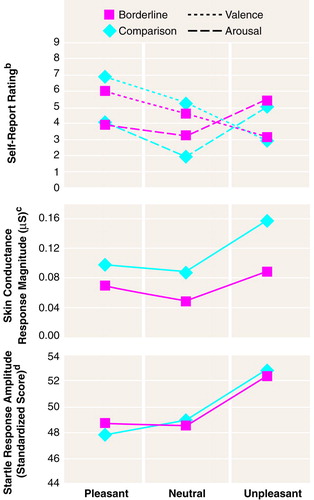

Table 1 shows all self-report and physiological data for the two groups of subjects. The slides selected from the International Affective Picture System were suitable for inducing different valence ratings. This was reflected in the repeated measures ANOVA by the overall effect for slide valence category, which was significant for valence and arousal (Figure 1). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences among all three affective qualities in valence ratings (for pleasant-neutral, F=62.99, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0003; for pleasant-unpleasant, F=202.53, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0002; for neutral-unpleasant, F=91.12, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0001) and in arousal ratings (for pleasant-neutral, F=25.00, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0003; for pleasant-unpleasant, F=34.50, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0002; for neutral-unpleasant, F=97.23, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0001). Furthermore, there was a significant overall group effect for valence but not for arousal ratings (Figure 1). The effects for interactions of group by slide valence were significant for valence ratings (F=3.49, df=2, 98, p=0.03) as well as for arousal ratings (F=3.48, df=2, 98, p=0.02). Regarding the interaction effects in valence self-rating, post hoc analyses revealed a trend toward a significant group effect for the unpleasant-pleasant contrast only (F=5.03, df=1, 49, p=0.02, adjusted p=0.06). Post hoc one-way ANOVAs showed that the subjects with borderline personality disorder evaluated pleasant slides as significantly less pleasant than did the normal subjects (F=9.73, df=1, 49, p=0.003), and the same was true for the neutral slides (F=6.10, df=1, 49, p=0.01). With regard to arousal ratings, the only significant group effect was found for the pleasant-neutral contrast (F=7.13, df=1, 49, p=0.01, adjusted p=0.03), and according to one-way ANOVA, the subjects with borderline personality disorder reported significantly greater arousal while viewing neutral slides (F=7.97, df=1, 49, p=0.006). The groups did not differ in either valence or arousal ratings in their emotional responses to unpleasant stimuli (Figure 1). At the start of the experiment, affective state did not differ between the groups, as measured by valence and arousal ratings.

As the results of one-way ANOVAs show, base rates of skin conductance level and heart activity did not differ between the groups during a rest period before the start of the experiment (F=0.03, df=1, 49, p=0.85, and F=0.04, df=1, 49, p=0.83, respectively), nor did startle responses show group effects for raw amplitude (F=0.20, df=1, 49, p=0.65) or raw onset (F=0.08, df=1, 49, p=0.77).

In the repeated measures ANOVA model, a main effect of diagnostic group was found for skin conductance response; there was also a significant slide valence effect but no interaction between group and slide valence (Figure 1). Post hoc comparisons indicated significant differences among all three affective qualities (for neutral-unpleasant, F=28.20, df=1, 49, p=0.0001, adjusted p=0.0003; for pleasant-unpleasant, F=11.60, df=1, 49, p=0.001, adjusted p=0.002; for pleasant-neutral, F=4.14, df=1, 49, p=0.04, adjusted p=0.04).

The groups did not differ in heart rate change. However, significant effects appeared in the testing for slide valence effects (F=3.24, df=2, 98, p=0.04) and for the interaction between group and slide valence (F=3.23, df=2, 98, p=0.04). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that during the presentation of unpleasant slides, heart rate changes were different from those during the presentation of pleasant slides (F=6.88, df=1, 49, p=0.01, adjusted p=0.03) and neutral slides (F=4.44, df=1, 49, p=0.04, adjusted p=0.08). The interaction effect was further determined by post hoc comparisons, revealing a trend for a group difference with regard to the pleasant-neutral contrast (F=4.93, df=1, 49, p=0.03, adjusted p=0.09). One-way ANOVAs did not show significant differences in heart rate change during viewing of pleasant and neutral slides.

As shown by ANCOVAs, the personality traits of impulsiveness and aggressiveness (total scores and subscores on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and the Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness) could not explain group effects in skin conductance response (for Barratt Impulsiveness Scale total score, F=0.03, df=1, 49, p=0.86; for Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness sum score of the first three subscales, F=0.13, df=1, 49, p=0.72).

Exclusion of data from three borderline personality disorder subjects and four normal comparison subjects who failed to respond to the startle probe did not change the results of the repeated measures ANOVAs (e.g., for skin conductance response, for overall group effect, F=6.22, df=1, 42, p=0.01; for slide valence effect, F=12.46, df=2, 84, p=0.0001).

Repeated measures ANOVA indicated no main effects for group with regard to raw onset and raw amplitude of the startle response elicited by the acoustic probe (F=1.69, df=1, 42, p=0.20, and F=0.02, df=1, 42, p=0.88, respectively). However, there was a main slide valence effect for raw amplitude (F=8.10, df=2, 84, p=0.0006; the interaction between group and slide valence was not significant), with post hoc analyses indicating a difference between unpleasant and neutral or pleasant slides (for unpleasant-neutral, F=14.36, df=1, 42, p=0.0005, adjusted p=0.001; for unpleasant-pleasant, F=11.13, df=1, 42, p=0.001, adjusted p=0.002). A significant slide valence effect was not found for blink latency raw scores.

Repeated measures ANOVA of the standardized blink amplitude scores produced results identical to those for raw scores (Figure 1). Using standardized blink latency scores, we found a significant slide valence effect (F=4.21, df=2, 84, p=0.01) and a significant interaction between group and slide valence (F=4.32, df=2, 84, p=0.01). Post hoc comparisons revealed that within the overall study group, latencies to unpleasant slides were significantly different from those to neutral slides (for unpleasant-neutral, F=10.35, df=1, 42, p=0.002, adjusted p=0.006). Post hoc analyses also indicated a group effect for the pleasant-unpleasant contrast (F=7.20, df=1, 42, p=0.01, adjusted p=0.03). According to one-way ANOVAs, startle latencies differed between the groups with regard not only to pleasant slides (F=6.12, df=1, 42, p=0.01) but also to unpleasant slides (F=5.58, df=1, 42, p=0.02).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study of patients with borderline personality disorder to assess self-report and physiological parameters of affective processing in response to experimental stimuli. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, neither self-report nor physiological data gave evidence of affective hyperarousal in borderline personality disorder. When borderline subjects were viewing standardized emotional stimuli, they did not show increased skin conductance responses or produce startle amplitudes significantly higher than those of normal comparison subjects. The pattern of physiological responses to stimuli of varying valence was quite similar in the borderline subjects and the normal comparison subjects. Consistent with previous findings in normal populations, both groups showed a significant potentiation of startle amplitude when viewing unpleasant slides (15, 16). Skin conductance response differed as a function of slide valence in both the clinical group and the comparison group, with unpleasant slides producing the highest and neutral slides the lowest skin conductance responses (16). Finally, heart rate changes corresponding to alterations in slide valence were also found, reflecting deceleration in response to aversive stimuli in either group (16).

While responses to negative stimuli were largely comparable, some data suggest that the subjects with borderline personality disorder showed a less pleasant reaction to positive pictures in comparison with the normal subjects. This was indicated by less positive self-ratings and further supported by heart rate acceleration and longer startle response latency (reflecting lower arousal) while viewing pleasant slides. This deviation may be explained by the pervasive dysphoric emotions in borderline personality disorder, which may dampen pleasant responses. This finding has to be replicated, since the analyses did not provide strong statistical support.

It was particularly interesting that the data revealed a decreased level of electrodermal responsiveness to affective stimuli in the subjects with borderline personality disorder. It is theorized that this responsiveness reflects stimulus-bound activation, which subsumes attentional and emotional processing in our design. Since skin conductance responses were found to be diminished in response not only to emotional but also to neutral stimuli, a decreased electrodermal responsiveness may indicate problems in attentional processing irrespective of the emotional nature of the stimuli. Low autonomic reactions were not reflected in the borderline personality disorder subjects’ self-ratings of their arousal experiences, which were quite similar to those of the normal comparison subjects. The subjects with borderline personality disorder even reported higher arousal ratings after viewing neutral slides. Several mechanisms to account for this dissociation between self-report and physiological data are possible. On the one hand, one may question whether self-ratings accurately reflect the emotional experience. Verbal communication of affective reactions is vulnerable to intentional distortion. Moreover, one should not forget that patients with borderline personality disorder possess intact associative-processing faculties, which allow “text-appropriate self-report ratings” that may not be identical to the real emotions (25). On the other hand, it has not yet been clarified how the different response systems interact. According to current knowledge, these systems are controlled by brain mechanisms that work partly independently of each other (13).

The finding of low autonomic responses in borderline personality disorder raises questions about common characteristics of personality functioning in psychopathic and borderline individuals, all the more since family studies suggest a genetic link between antisocial and borderline personality disorders (26). Psychophysiological studies on psychopathic persons have suggested that somatic hyporesponsiveness may be related to an impulsive, disinhibited temperament (8). In contrast to these findings, low electrodermal reactivity in our study of subjects with borderline personality disorder could not be explained by impulsiveness or aggressiveness. However, an absence of differential psychophysiological responses may impair flexible adaptation to the environment, not only in psychopathic but also in borderline individuals. Unlike psychopathic persons, clinical populations of female borderline patients are not at high risk for engaging in criminal behavior but, rather, for experiencing stressful interpersonal events, where they exhibit various externalizing behavioral problems, the consequences of which they probably cannot anticipate. In our study, borderline subjects were not characterized by high sensation seeking; however, it is questioned whether the Sensation-Seeking Scale adequately records this trait in females (27). Their relative physiological unresponsiveness may contribute to their high openness to emotional stimuli, which could have the function of compensating for feelings of underarousal and emptiness. Other findings also suggest essential differences between borderline and psychopathic subjects: the potentiation of startle response shown by borderline patients when viewing aversive slides is not compatible with emotional detachment, a main feature of the classical concept of psychopathy (28).

Because of certain methodological limitations, one should generalize from these results with caution. The study group was rather small, though comparable to those in other psychophysiological studies, and it was homogeneous and representative, thanks to careful recruitment (11, 12). Further studies should include an orienting paradigm consisting of the presentation of pure tones to differentiate between attentional and emotional processing. Another limitation that needs to be considered in interpreting the findings is that pleasant slides were rated as less arousing than unpleasant slides by clinical and nonclinical subjects alike. This may explain the absence of an inhibition of startle amplitude during the presentation of positive stimuli, as was reported in a number of earlier studies (14, 16). Rather low arousal ratings of the pleasant stimuli may have resulted from problems in the selection of suitably pleasant slide stimuli from the International Affective Picture System. Erotic images (which usually elicit the highest level of positive arousal) were excluded from the experiment because they might have evoked negative reactions in the female borderline patients, a majority of whom had sexual problems. Finally, the specificity of the psychophysiological findings we present should be verified by investigating clinical populations other than borderline patients or psychopathic individuals.

In conclusion, our data do not support the current theory of affect dysregulation in the sense of affective hyperarousal, which claims that intense emotional responses are the central feature of borderline personality disorder. Contrary to the hypothesized affective hyperarousal, the low electrodermal reactions found in this group of female borderline subjects suggest hyporesponsiveness. Data from studies on antisocial personalities suggest that somatic underarousal may be a heritable risk factor for developing nonadaptive, excitement-seeking modes of behavior (8). However, low autonomic reactivity may also be mediated by learning experiences. Carrey et al. (29) reported lower electrodermal responses in abused children when they were viewing slides with everyday emotional or cognitive content. Chronic stress in persons with borderline personality disorder may initiate a process of down-regulating autonomic responses. In this study, emotional stimuli that did not relate to the individual personal context of the participants were used. Physiological responses to stimuli that the individual identifies as specific stressors may be different. Further research is needed to understand the processing of emotional content in borderline personality disorder.

Received May 18, 1998; revision received Feb. 17, 1999; accepted March 3, 1999. From the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technical University of Aachen. Address reprint requests to Dr. Herpertz, Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technical University of Aachen, Pauwelsstr. 30, D-52057 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank J. Silny for technical advice; G. Lukas, U. Gretzer, and J. Nutzmann for technical assistance; A. Schuerkens for statistical support; and A. Rodón for language and general editing.

|

FIGURE 1. Self-Reports of Affective Valence and Arousala, Skin Conductance Response, and Standardized Startle Response Amplitude in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder (N=24) and Normal Comparison Subjects (N=27) During Presentation of Pleasant, Neutral, and Unpleasant Photographic Slides

aAccording to the Self-Assessment Manikin, for valence ratings, 1=extremely unpleasant and 9=extremely pleasant; for arousal ratings, 1=very low arousal and 9=very high arousal.

bFor valence, significant effect of group (F=7.11, df=1, 49, p=0.01) and valence (F=132.05, df=2, 98, p=0.0001). For arousal, significant effect of valence (F=54.68, df=2, 98, p=0.0001); no group effect (F=1.43, df=1, 49, p=0.23).

cSignificant effect of group (F=8.29, df=1, 49, p=0.005) and slide valence (F=15.14, df=2, 98, p=0.0001).

dSignificant effect of slide valence (F=8.82, df=2, 84, p=0.0003); no group effect. Three borderline subjects and four comparison subjects were startle nonresponders.

1. Linehan MM: Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

2. Herpertz S, Gretzer A, Steinmeyer EM, Muehlbauer V, Schuerkens A, Sass H: Affective instability and impulsivity in personality disorder: results of an experimental study. J Affect Disord 1997; 44:31–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hare RD: Electrodermal and cardiovascular correlates of psychopathy, in Psychopathic Behavior: Approaches to Research. Edited by Hare RD, Schalling D. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1978, pp 107–143Google Scholar

4. Hare RD: Psychopathy and electrodermal responses to nonsignal stimulation. Biol Psychiatry 1978; 6:237–246Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Quay HC: Psychopathic personality as pathological stimulation-seeking. Am J Psychiatry 1965; 122:180–183Link, Google Scholar

6. Zuckerman M: Sensation-Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1979Google Scholar

7. Sass H: Psychopathy—Sociopathy—Dissociality: The Differential Typology of Personality Disorders. Berlin, Springer, 1987Google Scholar

8. Raine A: Autonomic nervous system factors underlying disinhibited, antisocial, and violent behavior. Ann NY Acad Sci 1996; 794:46–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Filion DL, Dawson ME, Schell AM: The psychological significance of human startle eyeblink modification: a review. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 47:1–43Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN: Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychol Rev 1990; 97:377–395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cook EW III, Hawk LW, Davis TL, Stevenson VE: Affective individual differences and startle reflex modulation. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:5–13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ: Emotion in the criminal psychopath: startle reflex modulation. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:82–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Öhman A, Birbaumer N: Psychophysiological and cognitive-clinical perspectives on emotion: introduction and interview, in The Structure of Emotion. Edited by Birbaumer N, Öhman A. Seattle, Hogrefe & Huber, 1993, pp 3–17Google Scholar

14. Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN, Lang PJ: Startle reflex modification: emotion or attention? Psychophysiology 1990; 27:513–522Google Scholar

15. Bradley MM, Greenwald MK, Hamm AO: Affective picture processing, in The Structure of Emotion. Edited by Birbaumer N, Öhman A. Seattle, Hogrefe & Huber, 1993, pp 48–68Google Scholar

16. Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Lang PJ: Probing picture perception: activation and emotion. Psychophysiology 1996; 33:103–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham HM, Russakoff LM: International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE). White Plains, NY, New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, Westchester Division, 1993Google Scholar

18. Barratt ES: Impulsiveness subtraits: arousal and information processing, in Motivation, Emotion, and Personality. Edited by Spence JT, Izard CE. New York, Elsevier-North Holland, 1985, pp 137–146Google Scholar

19. Hampel R, Selg H: FAF—Questionnaire for the Assessment of Factors of Aggressiveness. Göttingen, Germany, Hogrefe, 1975Google Scholar

20. Buss AH, Durkee A: An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Clin Psychol 1957; 21:343–348Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention (CSEA): The International Affective Picture System: Photographic Slides. Gainesville, Fla, Center for Research in Psychophysiology, 1995Google Scholar

22. Lang PJ: Behavioral treatment and biobehavioral assessment: computer applications, in Technology in Mental Health Care Delivery. Edited by Sidowski JB, Johnson JH, Williams TA. Norwood, NJ, Albex, 1980, pp 109–137Google Scholar

23. Schandry R: Textbook of Psychophysiology. Weinheim, Germany, Beltz, 1994Google Scholar

24. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1997Google Scholar

25. Patrick CJ, Cuthbert BN, Lang PJ: Emotion in the criminal psychopath: fear image processing. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:523–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Soloff PH, Millward JW: Psychiatric disorders in the families of borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ball IL, Farnili D, Wangeman JF: Sex and age differences in sensation seeking: some national comparisons. Br J Psychol 1984; 75:257–265Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Cleckley H: The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues About the So-Called Psychopathic Personality, 5th ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1976Google Scholar

29. Carrey NJ, Butter HJ, Persinger MA, Bialik RJ: Physiological and cognitive correlates of child abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1067–1075Google Scholar