Panic Attacks and Suicide Attempts in Mid-Adolescence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to investigate the association of panic attacks and suicide attempts in a community-based sample of 13–14-year-old adolescents. METHOD: The data are from a survey of 1,580 students in an urban public school system located in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Logistic regression methods were used to estimate associations between panic attacks and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. RESULTS: Controlling for demographic factors, major depression, the use of alcohol, and the use of illicit drugs, the authors found that adolescents with panic attacks were three times more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and approximately two times more likely to have made suicide attempts than were adolescents without panic attacks. CONCLUSIONS: This new epidemiologic research adds to the evidence of an association between panic attacks and suicide attempts during the middle years of adolescence.

Some epidemiologic research suggests that adults with a lifetime history of panic disorder might be at greater risk for suicide attempts (1). The present investigation looks for evidence of this association earlier in the life span, seeking to estimate the strength of association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicide attempts in a community sample of adolescents.

Weissman et al. (1), analyzing lifetime history data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study, reported that “both panic attacks and panic disorder, as compared with other psychiatric disorders, are associated with increase in the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts” (p. 1212). Compared with subjects who had no psychiatric disorders, subjects with panic disorder were 17–18 times more likely to report having made one or more suicide attempts. Compared with subjects who had any psychiatric disorder, the odds ratio—1.67—was much lower.

Hornig and McNally (2) reanalyzed the same ECA lifetime history data, using different methods, and reached the opposite conclusion, i.e., that panic disorder was not associated with a greater risk of suicide attempts. Their analysis differed from that of Weissman et al. (1) in two ways. First, Weissman et al. controlled for psychiatric disorders one at a time, but Hornig and McNally (2) controlled for them in aggregate. Second, Hornig and McNally controlled for schizophrenia, a disorder associated with a greater suicide risk (3).

Newer, prospectively gathered ECA data and other epidemiologic evidence suggest that major depression, alcohol dependence, and cocaine use are associated with a greater risk of suicide attempts and panic attacks during follow-up observation intervals (4, 5). The co-occurrence of panic disorder and major depression has been reported in both adult (6) and adolescent (7) samples. Estimates of comorbidity between panic disorder and depression vary from 20% to 75% (8). Thus, in research on panic and suicide it is essential to adjust for the presence of major depression and drug use.

Most clinical studies do not find an association between panic disorder and suicide attempts in the absence of comorbid disorders such as affective disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders (9–12). Warshaw et al. (12) reported on a naturalistic prospective study of 527 patients recruited in clinics and mental hospitals. In their study, almost all of the suicide attempts among patients with panic disorder were reported by individuals who had a co-occurring depression, although not necessarily major depression.

This disparity of results, with some studies supporting and others refuting the association of panic attacks (or panic disorder) and greater suicide risk, may reflect differences in the type of subjects investigated (population-based and clinical samples), the severity of comorbidity, and the amount of information available. Detailed information regarding psychosocial factors, mild disorders (e.g., dysthymia), and personality disorders is less likely to be gathered in epidemiologic studies (12).

The lifetime prevalence of panic disorder in adult populations is estimated to be 1.6%–2.0% (13). Data on panic disorder and panic attacks among adolescents stem from small epidemiologic studies and clinical reports, reviewed by Moreau and Weissman (14) and Ollendick et al. (15). Although panic disorder is infrequent in mid-adolescence (16), panic attacks are not. For example, in a study of 95 students whose mean age was 14.5 years, the lifetime prevalence of at least one panic attack approached 12% (17). Other population-based studies have reported a higher prevalence of panic attacks among adolescents (7, 18, 19). Prevalence figures are hard to compare because the age range of the adolescents sampled and the ascertainment of panic attacks have differed from one study to another.

With some notable exceptions (20–26), studies of suicide attempts among adolescents have relied on clinical samples (e.g., references 27–29). It is unclear to what extent findings from clinical samples generalize to community samples. The lifetime prevalence of attempts reported in community studies has ranged from 3.5% to 9% and tends to be higher for self-report by high school students on anonymous surveys than for structured interviews (26, 30). Little is known about the possible association between panic attacks and suicide attempts among adolescents in community settings. With few exceptions (26, 31), this association has received little attention. The present investigation explored this hypothesized association in a population-based study of adolescents.

METHOD

This investigation represents a cross-sectional study of the association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a community sample of adolescents, most of whom were 13–14 years old at the time of assessment.

Sample

This study population consists of students in an urban public school system located in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Two successive cohorts of first graders were recruited beginning in 1985 (N=2,311). The sample was drawn from 43 classrooms located in 19 public elementary schools in five city areas, each chosen to reflect different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Yearly assessments of all students remaining in the public school system were conducted between 1989 and 1994. At baseline, the 2,311 students were evenly divided between boys and girls. Seventy-five percent were African American, and the mean age was 6 years. Over time, as a disproportionate number of white families transferred their children to other school systems, a preponderance of African American students emerged (32). Detailed descriptions of the study have been published elsewhere (32, 33).

For the purpose of this investigation, our sample consisted of 1,580 students interviewed in 1993–1994, when their panic attacks and suicide-related behaviors were first assessed. Of the 1,580 students, 767 were boys and 813 girls. Two hundred ninety-three were Caucasian and 1,287 non-Caucasian (mostly African American). Written informed consent was obtained from parents of participating students. Verbal assent was obtained from all participating adolescents.

Study Assessments

Lifetime history of at least one panic attack was considered present when students answered affirmatively to the question, “Have you ever in your life had a spell or attack when all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or very uneasy in situations when most people would not be afraid or anxious?” This question is from the National Comorbidity Survey (34).

An adaptation of the depression section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used to assess major depression. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a standardized, comprehensive diagnostic interview designed according to the definitions of the diagnostic criteria for research of ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. In adult samples, both test-retest and interrater reliability studies of this instrument have confirmed good to excellent kappa coefficients for most diagnostic sections (35).

Lifetime history of suicide attempts and/or suicidal ideation was ascertained through an amended version of the relevant Composite International Diagnostic Interview questions. The following two questions were used to ascertain the presence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: “Have you ever felt so low you thought about hurting yourself very very badly, on purpose?” and, “Have you ever tried to hurt yourself very very badly, on purpose?”

Information regarding alcohol and drug use was obtained through the same structured interview.

Data Analysis

Chi-square analysis was used as an aid to interpretation of the observed variation in occurrence of suicidal ideation across subgroups of subjects who had no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, subjects with a history of suicidal ideation but no suicide attempts, and subjects with a history of suicide attempts.

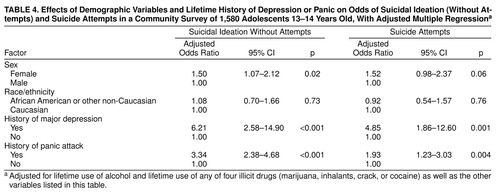

We used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratio of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among subjects with and without a lifetime history of major depression and panic attacks. All estimates of odds ratio were adjusted for demographic variables (sex and race/ethnicity), a lifetime major depression diagnosis, and a lifetime history of alcohol or use of any of four illicit drugs (marijuana, inhalants, crack, or cocaine).

RESULTS

Estimated lifetime prevalence proportions for major depression, panic attacks, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts are shown in Table 1. Being female and race/ethnicity were not found to be significantly associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in the bivariate analysis (Table 2). Higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were associated with a lifetime history of panic attacks and major depression (Table 2).

The highest prevalence of suicidal ideation was evident among the 12 adolescents with both major depression and panic attacks (Table 3). The highest prevalence of suicide attempts was evident among the 13 adolescents with major depression and no panic attacks. These figures should be viewed cautiously because the number of adolescents in each category was small (Table 3).

As shown in Table 4, the logistic regression models revealed that adolescents with history of panic attacks were approximately three times more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and about two times more likely to have made suicide attempts than adolescents without panic attacks. Adolescents with a history of major depression were approximately six times more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and almost five times more likely to have made suicide attempts than adolescents with no history of major depression. These odds were adjusted for demographic variables (sex and race-ethnicity), lifetime history of major depression, history of alcohol use, and the use of any of four illicit drugs (Table 4).

As a check on the validity of our logistic regression adjustment procedures, we conducted an exploratory search for possible interactions between variables. We did not find that interaction terms improved the fit of the model (alpha=0.10).

DISCUSSION

This study adds new population-based estimates of the association between a lifetime history of panic attacks and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the middle years of adolescence. The logistic regression models indicated that adolescents with a lifetime history of panic attacks were more likely to have expressed suicidal ideation and to have made suicide attempts than those without a lifetime history of panic attacks. These findings were obtained with statistical control for demographic variables and other characteristics suspected to affect the occurrence of suicide attempts (e.g., major depression, alcohol use, and illicit drug use).

Although this study has a number of important strengths, including the use of a structured interview and standard diagnostic criteria to ascertain psychiatric disturbances, several limitations are especially noteworthy and deserve comment. A principal limitation of this study is the reliance on cross-sectional lifetime prevalence data, which cannot disentangle the temporal sequences that underlie observed associations between a lifetime history of panic attacks and a history of suicide attempts. Of course, this limitation also applies to the work of Weissman et al. (1), which remains the most cited published article on this association. Another noteworthy limitation is the lack of control or adjustment for other specific psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders and schizophrenia, which were not assessed in this investigation. However, it should be noted that the prevalence of schizophrenia in early- to mid-adolescence is very low (36). Last, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview has been validated only in adult populations. Since, according to DSM-IV, adolescent and adult depression present with similar affective, cognitive, motivational, and vegetative symptoms, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview might well be valid among adolescents. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that our adapted question on suicide attempts, designed to be responsive to parental concerns about a sensitive topic, might be broad enough to encompass self-mutilation and self-harming behaviors in general, rather than suicide attempts specifically. This is an issue we are probing in a new follow-up assessment of this sample of adolescents.

Notwithstanding limitations such as these, the association between panic attacks and suicide attempts found in this study parallels the ECA findings reported by Weissman et al. (1). Anthony and Petronis (37) expressed concern that reliance on cross-sectional lifetime prevalence ECA data might have created a spurious association between a history of panic attacks and a history of suicide attempts (1, 38). For this reason, they completed a prospective nested case-control study of 40 ECA respondents who had recently attempted suicide and 160 matched control subjects. Controlling for demographic factors, psychiatric disorders, and drug use, they also found that adults with a lifetime history of panic attacks were at greater risk of suicide attempts (37). A recent study based on a community sample of children and adolescents aged 9 to 17 years (31) revealed that panic attacks were significant predictors of suicide risk, after adjustments for relevant psychiatric disorders.

The present study adds to the accumulating evidence of an association between panic attacks and suicide attempts and observes this association in a community sample of adolescents. Two types of studies might confirm that these findings are not the result of a spurious association: 1) conventional epidemiologic case-control studies of adolescents with panic attacks and 2) experimental studies aimed at ascertaining whether preventive treatment of panic attacks might reduce the risk of ensuing suicide attempts.

Panic attacks were ascertained in this investigation in essentially the same manner as in the ECA survey. In all likelihood, some students who reported panic attacks in this study, as well as some adults who reported them in the ECA study, would have met only one DSM-IV criterion for panic attacks. DSM-IV criteria require at least four from a list of 11 symptoms of panic attacks. The list includes symptoms such as palpitations, sweating, and trembling, among others. Had we ascertained the presence of panic attacks using DSM-IV criteria, a group with more severe panic attacks would have been selected. In such a group, the odds of reporting suicide attempts might well have been higher than is conveyed by the estimates reported here.

Andrews and Lewinsohn (26), analyzing data from their community study of suicide attempts among high school students, found no association between panic disorder and suicide attempts. However, their sample included only 14 adolescents with a lifetime history of panic disorder, which constrained the statistical power of their analysis and the information value of their study. Given the low prevalence of panic disorder among adolescents (16), it is not surprising that only a relatively small number of students met the criteria for a diagnosis of panic disorder. Focusing on students who reported panic attacks, a more frequent occurrence, has enabled us to base our estimates on more than 300 students with a lifetime history of panic attacks.

This new epidemiologic research extends to adolescents an important finding from adult investigations, i.e., that individuals with panic attacks seem to be more likely to experience suicidal ideation and make suicide attempts than those without panic attacks. Given the current concern about adolescent suicide, research findings that suggest potential risk factors for suicide attempts in this population may contribute to better-informed screening and prevention efforts. Clinicians are well advised to inquire routinely about past suicidal ideation and suicide attempts during the initial interview with adolescents who present with a history of panic attacks and to monitor for emergence of these symptoms during treatment.

Readers also may be interested to know that recent epidemiologic data suggest an increased occurrence of suicidal deaths among African American youths in the United States (39). Our epidemiologic sample consisted primarily of African American adolescents. Hence, these empirical findings may have some value to clinicians and public health practitioners who seek to curb this trend.

Received June 30, 1998; revision received Jan. 14, 1999; accepted March 4, 1999. From the Kennedy Krieger Institute; the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health, Baltimore, Md. Address reprint requests to Dr. Anthony, Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, Hampton House 893, 624 N. Broadway, Baltimore, MD 21205; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported primarily by NIMH grants MH-47447 and MH-01456 and training grant award MH-14592 and by National Institute of Drug Abuse grant DA-09592.

|

|

|

|

1. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Markowitz JS, Ouellette R: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1209–1214Google Scholar

2. Hornig CD, McNally RJ: Panic disorder and suicide attempt: a reanalysis of data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:76–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Appleby L: Suicide in psychiatric patients: risk and prevention. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:749–758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Anthony JC, Tien AY, Petronis KR: Epidemiologic evidence on cocaine use and panic attacks. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129:543–549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Petronis KR, Samuels JF, Moscicki EK, Anthony JC: An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for suicide attempts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990; 25:193–199Medline, Google Scholar

6. Andrade L, Eaton WE, Chilcoat H: Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study: symptom profiles. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:363–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Macaulay JL, Kleinknecht RA: Panic and panic attacks in adolescents. J Anxiety Disorders 1989; 3:221–241Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Andrade L, Eaton WE, Chilcoat H: Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study: age of onset. Psychol Med 1996; 26:991–996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Cox BJ, Direnfeld DM, Swinson RP, Norton GR: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:882–887Link, Google Scholar

10. Friedman S, Jones JC, Chernen L, Barlow DH: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among patients with panic disorder: a survey of two outpatient clinics. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:680–685Link, Google Scholar

11. Beck AT, Steer RA, Sanderson WC, Skeie TM: Panic disorder and suicidal ideation and behavior: discrepant findings in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1195–1199Google Scholar

12. Warshaw MG, Massion AO, Peterson LG, Pratt LA, Keller MB: Suicidal behavior in patients with panic disorder: retrospective and prospective data. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:235–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Gruenberg E, Burke JD Jr, Regier DA: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:949–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Moreau D, Weissman MM: Panic disorder in children and adolescents: a review. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1306–1314Google Scholar

15. Ollendick TH, Mattis SG, King NJ: Panic in children and adolescents: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:113–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Whitaker A, Johnson J, Shaffer D, Rapaport JL, Kalikow K, Walsh BT, Davies M, Braiman S, Dolinshy A: Uncommon troubles in young people: prevalence estimates of selected psychiatric disorders in a non-referred adolescent population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:487–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hayward C, Killen JD, Taylor CB: Panic attacks in young adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1061–1062Google Scholar

18. Zgourides GD, Warren R: Prevalence of panic in adolescents: a brief report. Psychol Rep 1988; 62:935–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. King NJ, Gullone E, Tonge BJ, Ollendick TH: Self-reports of panic attacks and manifest anxiety in adolescents. Behav Res Ther 1993; 31:111–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Harkavy Friedman JMH, Asnis GM, Boeck M, DiFiore J: Prevalence of specific suicidal behaviors in a high school sample. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1203–1206Google Scholar

21. Joffe RT, Offord DR, Boyle MH: Ontario child health study: suicidal behavior in youth age 12–16 years. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1420–1423Google Scholar

22. Velez CN, Cohen P: Suicidal behavior and ideation in a community sample of children: maternal and youth reports. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:349–356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL: A longitudinal study of suicidal ideation in young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:597–603Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Garrison CZ, Jackson KL, Addy CL, McKeown RE, Waller J: Suicidal behaviors in young adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 133:1005–1014Google Scholar

25. Garrison CZ, McKeown RE, Valois RE, Vincent ML: Aggression, substance abuse, and suicidal behaviors in high school students. Am J Public Health 1993; 83:179–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM: Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:655–662Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Brent DA: Correlates of medical lethality of suicidal attempts in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:87–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Allan MJ, Brown RV: Suicidality in affectively disordered adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:586–593Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kosky R, Silburn S, Zubrick SR: Are children and adolescents who have suicidal thoughts different from those who attempt suicide? J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:38–43Google Scholar

30. Shaffer D, Vieland V, Garland A, Rojas M, Underwood M, Busner C: Adolescent suicide attempters: response to suicide prevention programs. JAMA 1990; 264:3151–3155Google Scholar

31. Gould MS, King R, Geenwald S, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Kramer R, Flisher AJ, Goodman S, Canino G, Shaffer D: Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:915–923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Chilcoat HD, Dishion TJ, Anthony JC: Parent monitoring and the incidence of drug sampling in urban elementary school children. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141:25–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kellam SG, Rebok GW, Ialongo N, Mayer LS: The course and malleability of aggressive behavior from early first grade into middle school: results of a developmental epidemiologic-based preventive trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:259–281Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Keyl PM, Eaton WW: Risk factors for the onset of panic disorder and other panic attacks in a prospective population based study. Am J Epidemiol 1990; 131:301–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Wittchen H-U: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Florenzano RU: Chronic mental illness in adolescence: a global overview. Pediatrician 1991; 18:142–149Medline, Google Scholar

37. Anthony JC, Petronis KR: Panic attacks and suicide attempts (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Panic disorder, comorbidity and suicide attempts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:805–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Gibbs JT: African-American suicide: a cultural paradox. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1997; 27:68–79Medline, Google Scholar