Sertraline in the Treatment of Panic Disorder: A Double-Blind Multicenter Trial

Abstract

Objective: This study determined the efficacy and safety of sertraline in the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Method: The study was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, flexible-dose comparison of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. After a 2-week single-blind placebo lead-in, 168 patients entered a 10-week double-blind phase in which they were randomly assigned to treatment with either sertraline or placebo.Results: Sertraline was significantly more effective than placebo in decreasing the number of full and limited-symptom panic attacks. Among patients who completed the study, the mean number of panic attacks per week dropped by 88% in the sertraline-treated patients and 53% in the placebo-treated patients. Sertraline-treated patients also had significantly more improvement than placebo-treated patients in scores on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, patient global evaluation, and Clinical Global Impression severity of illness and global improvement scales. Overall, patients tolerated sertraline well, and only 9% terminated treatment because of side effects.Conclusions: Sertraline is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1189-1195

Tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, and benzodiazepines have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder (1). The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a pharmacologic profile that offers potential advantages in treating patients with panic disorder. Tricyclic antidepressants are frequently not tolerated in panic patients because of anticholinergic side effects, “jitteriness syndrome” in the first few weeks of treatment (2), and weight gain with long-term administration (3). MAO inhibitors marketed in the United States require dietary restrictions and have a high rate of nighttime insomnia and daytime lethargy (1). Benzodiazepines have sedative and psychomotor side effects and substantial dependence and withdrawal liability, and significant rebound is observed even after 8 weeks of acute treatment (4). SSRIs have few of these potential adverse effects.

A consensus panel of experts (5) has recommended an SSRI as the first-line pharmacologic treatment for panic disorder, despite the fact that few placebo-controlled studies demonstrating efficacy for SSRIs have been reported to date. Four small trials of fluvoxamine (6-9) demonstrated that fluvoxamine is superior to placebo. Two larger placebo-controlled trials of paroxetine demonstrated efficacy (10, 11), but in one of these (10), patients received both paroxetine and cognitive therapy. To our knowledge, there have been no positive reports of placebo-controlled trials of other SSRIs for the treatment of panic disorder to date.

The SSRI sertraline has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of depression (12) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (13), but so far published information on treating panic disorder with sertraline has been limited to case reports (14, 15). We report here the results from a large, multicenter, placebo-controlled study designed to assess the efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder.

METHOD

The study was a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, flexible-dose comparison of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with DSM-III-R panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. After a 2-week single-blind placebo lead-in, patients entered a 10-week double-blind phase in which they were randomly assigned to treatment with either sertraline (25 mg/day for 1 week then flexible titration to between 50 and 200 mg/day) or placebo. As the study was designed to assess pharmacologic treatment of panic disorder, concurrent psychotherapy, including behavioral therapy, was not allowed during the study.

Patients

The study was conducted at 10 sites. Patient recruitment at each site was performed in accordance with the procedures of each site’s institutional review board. After a thorough description of the study to potential subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The study group consisted of male and female outpatients who were 18 years of age or older and met the DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder, as assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version, part I (16).

Subjects were required to have a minimum of four panic attacks, at least one of which was unanticipated, during the 4 weeks before day 1 of the placebo lead-in and at least three, but no more than 100, DSM-III-R-defined panic attacks during the 2-week single-blind lead-in phase. In addition, subjects had to have total scores of 18 or higher on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (17) and 17 or lower on the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (18) at the baseline randomization visit. Patients with current DSM-III-R major depression, organic mental disorders, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder were excluded from the trial, as were those with a principal diagnosis of DSM-III-R dysthymic disorder, any anxiety disorder other than panic disorder, or a personality disorder. Psychoactive substance use disorder within the past 6 months and a lifetime history of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder were other reasons for exclusion.

Subjects were required to stop taking all psychotropic medication, with the exception of chloral hydrate for sleep, before study entry. They were excluded if they had received regular daily therapy with any benzodiazepine within 1 month before the first medication dose in the double-blind phase or had a positive urine screen for benzodiazepines or a positive serum screen for alprazolam on either day 1 or 8 of the placebo lead-in period. Patients with any medical conditions deemed to be clinically significant were excluded; women of childbearing potential were required to use an effective means of birth control.

Dose and Administration

All patients received a single placebo tablet daily, identical in appearance to the 25-mg sertraline tablet, during the 2-week single-blind placebo lead-in. During the double-blind phase, the patients randomly assigned to sertraline took 25 mg of sertraline daily for the first week and 50 mg for the second week. After this, the daily dose was increased by 50 mg each week for patients who had not yet achieved a satisfactory clinical response. Any dose increase depended on the absence of dose-limiting side effects. The maximal daily dose was 200 mg; patients who responded well to less than the maximal dose continued with this dose for the remainder of the study. The patients took their medication once daily with the evening meal. The dose could be decreased at any time because of adverse events. The patients randomly assigned to placebo during the double-blind phase took a corresponding number of matching placebo tablets.

Study Procedures

During the double-blind phase, the patients were evaluated weekly for 4 weeks, then every 2 weeks for three more visits. Each patient maintained a daily diary of symptoms; this information was converted into weekly ratings on the Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale (19) of D.V. Sheehan. In the patient diary, “panic attacks” were defined by four or more and “limited-symptom attacks” by one to three of the criterion C panic disorder symptoms in DSM-III-R. Daily each patient recorded 1) the number of panic and limited-symptom attacks and 2) the duration of the anticipatory anxiety regarding having an attack. Panic attacks and limited-symptom attacks were categorized as unexpected (no cause) or situational (with cause). At each study visit during the double-blind phase the patients also completed a self-evaluation of their improvement, using the anchors of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (20) improvement scale. At the beginning and end of the double-blind phase they also completed the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (21), a validated quality of life scale. At each visit, clinicians assessed the patients with the following instruments: the Multicenter Panic Anxiety Scale (22), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, and the CGI severity of illness and global improvement scales (the global improvement scale was not completed at baseline). The Multicenter Panic Anxiety Scale assesses five aspects of panic disorder (frequency of attacks, degree of distress during attacks, anticipatory anxiety, phobic avoidance of situations, and impairment/interference with work functioning); each aspect is rated by using a 5-point scale (0 represents “none” or “not present”; 4 indicates “extreme frequency,” “distress,” “worry,” “avoidance,” or “impairment”). The CGI improvement scales were used to rate global improvement and also improvement in five discrete panic disorder symptom domains: panic attacks, anticipatory anxiety, phobic avoidance, social/family functioning, and occupational functioning.

Physical examinations were done at the beginning and end of the study; blood pressure, heart rate, and body weight were assessed at each visit. The following tests were performed at the beginning of the placebo lead-in and at the end of weeks 2 and 10 of the double-blind period: ECG, complete blood cell count with differential and platelet counts, chemistry screen, urinalysis, and testing of serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin for pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.

In addition, T3 uptake ratio and T4 were measured at day 1 of the placebo washout. A serum alprazolam screen and a urine drug screen (for benzodiazepines or drugs of abuse) were done on day 1 and day 8 of the placebo lead-in and at the end of weeks 2 and 10 of the double-blind period. Adverse events during treatment were documented by observation and open interview.

Statistical Procedures

The safety analyses included all patients who took at least one dose of medication during the double-blind phase and provided any follow-up data; patients included in the safety analysis who had baseline and postrandomization efficacy data were included in the efficacy analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Baseline characteristics

The two treatment groups’ ages, weights, Hamilton depression scores, and durations of illness at the end of the placebo washout period were compared by using analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with terms for center and treatment group. Chi-square tests were used to compare sex and race.

Efficacy

The primary efficacy variable was the total number of panic attacks per week as rated with the Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale; two other measures from this scale were the total number of limited-symptom attacks per week and the duration of anticipatory anxiety per week. The measures from the Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale were analyzed weekly and at endpoint (the last observation carried forward) with ANOVAs. For the analyses of these endpoint measures, the averages for the last 2 weeks were used; if week 1 data only were collected, those data were used. The model for the analyses of the number of panic attacks and limited-symptom attacks and the percentage of time with anticipatory anxiety included terms for treatment group, center, and treatment-by-center interaction, with baseline values used as covariates. Because these variables were not normally distributed, they were logarithmically transformed for the purposes of statistical analysis. These tests were done at the 0.05 level of significance.

A number of secondary efficacy measures were analyzed. For these variables, statistical significance was declared if the p value was 0.01 or less to adjust for multiple comparisons. For these secondary measures, the two treatment groups’ changes from baseline in scores on the Multicenter Panic Anxiety Scale, Hamilton anxiety scale, CGI severity rating, and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire were compared by using ANOVAs with treatment, center, treatment-by-center interaction, and baseline effects. The CGI improvement ratings (both patient- and clinician-rated versions) were analyzed with the same model but with the baseline values excluded.

Adverse events

If a patient reported multiple episodes of the same adverse event, the event was counted only once in the computation of incidence rates of adverse events; the severity assigned to the event was the highest level of severity recorded for the episodes. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the sertraline- and placebo-treated groups on 1) the rates of patients with any adverse experience and of individual adverse experiences, 2) the number of patients who discontinued treatment because of adverse experiences, and 3) the incidence of clinically significant laboratory abnormalities. Mean changes in vital sign measures and body weight from the end of the placebo lead-in to the end of week 10 (or patient discontinuation) in the sertraline- and placebo-treated groups were compared by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

During the double-blind phase, 168 patients were administered medication; 88 received placebo, and 80 received sertraline. For one patient taking placebo and one patient taking sertraline, follow-up efficacy data were not available. Thus, the efficacy analyses included 166 patients, 87 of whom were treated with placebo and 79 with sertraline.

The patients randomly assigned to sertraline and placebo did not differ on baseline demographic features (sex, racial background, and age), clinical characteristics (duration of illness, weekly numbers of panic and limited-symptom attacks, extent of anticipatory anxiety, and scores on the Multicenter Panic Anxiety Scale, Hamilton anxiety scale, CGI severity rating, and Hamilton depression scale), or social functioning as measured by the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire. Overall, 57% of the patients were female (96 of 168), 88% were white (147 of 168), and they had a mean age of 37.5 years (SD=11.5). The mean lengths of illness were 9.5 years (SD=10.1) and 8.6 years (SD=8.2), respectively, for those receiving sertraline and placebo. At baseline, their overall symptoms were of moderate to marked severity; the mean CGI severity score was 4.3 (SD=0.7) for the patients taking sertraline and 4.3 (SD=0.6) for those taking placebo. They were experiencing frequent panic attacks: a mean of 6.4 (SD=7.1) and 5.2 (SD=5.7) panic attacks per week for the sertraline and placebo groups, respectively; the corresponding numbers of limited-symptom attacks were 9.2 (SD=9.7) and 7.2 (SD=7.3), respectively. In addition to their symptoms during attacks, at baseline the patients spent a mean of 31% of their time (SD=26%) worrying about having another attack. At baseline, 48 of the sertraline-treated and 51 of the placebo-treated patients met the DSM-III-R criteria for agoraphobia in addition to panic disorder. In contrast to their substantial anxiety symptoms, the patients had little depression: their mean scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were 10.9 (SD=4.2) for the sertraline group and 11.4 (SD=3.8) for the placebo group.

Patient Disposition

Thirty-six patients withdrew from treatment during the study; 74% of the sertraline-treated patients (N=59) and 83% of the placebo-treated patients (N=73) completed the full 12 weeks of double-blind treatment. The most frequent reason for discontinuation of sertraline treatment was adverse experiences; 9% of the sertraline-treated patients (N=7) stopped taking the medication because of adverse experiences, in comparison to 1% of the placebo-treated patients (N=1). In the placebo group, insufficient clinical response was the most common reason for discontinuation; 7% of the placebo-treated patients (N=6) and 1% of the sertraline-treated patients (N=1) stopped treatment because of lack of efficacy.

Dose

The mean duration of therapy was 58.2 days (SD=23.2) for the sertraline group and 64.2 days (SD=18.3) for the placebo-treated group. At endpoint, the mean dose received by the sertraline-treated patients was 126 mg/day (SD=62). By week 4, all of the sertraline-treated patients were taking at least 50 mg/day.

Efficacy

Number of attacks

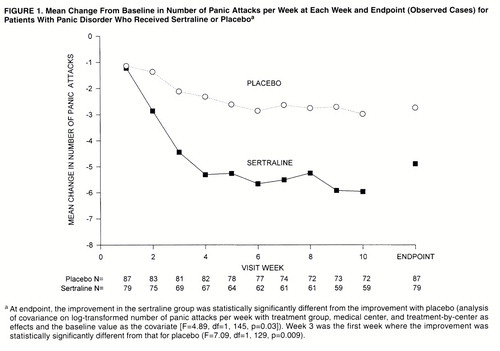

The study’s primary efficacy measure was the number of panic attacks per week, derived from the Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale. The mean change from baseline in the number of panic attacks per week is presented in Figure 1. At endpoint, the average percentage decrease from baseline in number of panic attacks was 77% for the sertraline-treated patients and 51% for the placebo-treated patients. Among the study completers, the corresponding decreases in panic attacks were 88% in the sertraline group and 53% in the placebo group. The reduction in panic attack frequency at endpoint was significantly greater in the sertraline group than the placebo group (F=4.89, df=1, 145, p=0.03), and significantly more sertraline-treated patients (62%, N=49) than placebo-treated patients (46%, N=40) were free of panic attacks at endpoint (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.04).

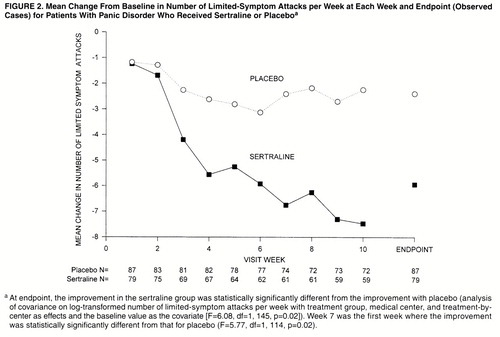

The mean change from baseline in the number of limited-symptom attacks per week is presented in Figure 2. The mean number of limited-symptom attacks per week decreased by 5.9 (SD=8.8) in the sertraline group and 2.4 (SD=7.0) in the placebo group; the reduction in limited-symptom attacks at endpoint was significantly greater in the sertraline group than in the placebo group (F=6.08, df=1, 145, p=0.02).

Anxiety

The level of anticipatory anxiety decreased in both the sertraline- and placebo-treated patients as the study progressed. Although the percentage of time spent worrying about having a panic attack was lower at endpoint in the sertraline group (median=4.4%, interquartile range=0.0%–20.3%) than in the placebo group (median=10.3%, interquartile range=1.3%–26.8%), the reductions in anticipatory anxiety from baseline were not statistically different in the two groups (F=2.16, df=1, 145, p=0.14).

From baseline to endpoint, the scores on the Multicenter Panic Anxiety Scale decreased more in the sertraline group (mean decrease=6.6, SD=5.5) than in the placebo group (mean=4.9, SD=5.2), but the reductions in the two groups were not statistically different (F=4.30, df=1, 145, p=0.04).

At endpoint the sertraline-treated patients showed more improvement than the placebo-treated patients on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, but the reductions of the two groups were not statistically different (F=4.71, df=1, 145, p=0.03).

Clinical Global Impression

Investigator assessments of the patients with the CGI were consistent with the improvement found on other measures. Both the CGI severity and global improvement scores revealed significantly greater improvement at endpoint in the patients treated with sertraline than in the placebo-treated patients (severity: F=13.35, df=1, 145, p<0.001; improvement: F=15.83, df=1, 146, p<0.001). On the CGI improvement subscale for panic attacks, the sertraline-treated patients showed significantly more improvement than did the patients taking placebo (F=14.27, df=1, 146, p<0.001). The sertraline-treated patients also showed more improvement than the placebo-treated patients on the other four CGI subscales, but the differences between treatment groups did not reach statistical significance (anticipatory anxiety: F=4.81, df=1, 146, p=0.03; phobic avoidance: F=4.50, df=1, 146, p=0.04; social/family functioning: F=5.75, df=1, 146, p=0.02; occupational functioning: F=4.12, df=1, 146, p=0.04).

In the patient ratings of improvement, the patients taking sertraline showed significantly more improvement than the patients taking placebo at endpoint (F=22.35, df=1, 146, p<0.001) and at all study visits from week 3 onward.

Quality of life

Patients in both the sertraline and placebo groups rated the quality of their lives as better after treatment; the patients taking sertraline had significantly higher ratings than did the placebo-treated patients on the total Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (F=7.94, df=1, 125, p=0.006). The sertraline-treated patients also had significantly greater improvement, between baseline and endpoint, in their satisfaction with their drug therapy than did the placebo-treated patients (F=15.54, df=1, 123, p<0.001).

Safety

Vital signs, ECG, laboratory tests

There were no significant differences between the sertraline- and placebo-treated patients in change from baseline to final visit in pulse or blood pressure; the patients taking sertraline lost a mean of 2.41 lb (SD=5.54) during this interval, while the patients taking placebo gained 0.04 lb (SD=3.69) (difference between groups: Wilcoxon z= –2.99, N=167, p=0.003). No clinically significant ECG abnormalities occurred during the study. The sertraline- and placebo-treated patients did not differ in the incidence of clinically significant laboratory test abnormalities. No patients were eliminated from the study because of abnormalities in laboratory test results or vital signs.

Adverse experiences

Although adverse events were infrequent overall, a higher percentage of sertraline-treated patients (9%, N=7) than placebo-treated patients (1%, N=1) discontinued treatment because of adverse experiences (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.03). Only two sertraline patients discontinued treatment because of adverse experiences during the first week of double-blind treatment, while receiving the 25-mg/day titration dose.

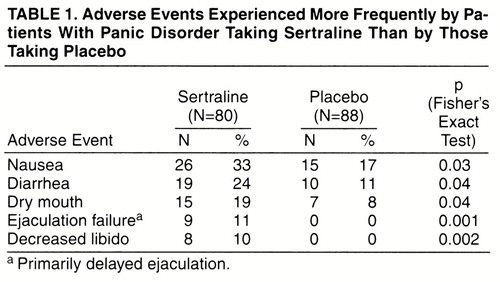

Adverse experiences were reported by 93% of the sertraline-treated patients (N=74) and 94% of the placebo-treated patients (N=83). Five adverse experiences occurred more frequently in the sertraline-treated patients than in the placebo-treated patients. The incidence rates for these adverse experiences in the sertraline and placebo groups are shown in table 1. These adverse experiences are similar to those previously reported in patients with depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder who were treated with sertraline. The vast majority of adverse experiences in each treatment group were mild or moderate in severity. The only adverse event (exacerbation of asthma secondary to inhalation of paint fumes) during the study that was deemed to be serious (e.g., life threatening or resulting in hospitalization) occurred in a patient taking placebo.

DISCUSSION

The NIMH consensus conference on the treatment of panic disorder (23) stressed that adequate determination of the efficacy of any treatment for panic requires that outcome be assessed in the following key clinical dimensions of the disorder: major and limited-symptom panic attacks, phobic avoidance, nonpanic anxiety, functional impairment, and quality of life. The results of the current study provide strong evidence that sertraline is a well-tolerated and highly effective treatment that achieves improvement in most measures of these key clinical aspects of panic disorder. In addition, the reduction from baseline in mean panic attack frequency at endpoint with sertraline in the current study (approximately 80%) was similar to that for alprazolam in the phase I cross-national alprazolam panic studies (70%) (24).

Time Course of Improvement

Benzodiazepines demonstrate significantly greater efficacy on most measures than placebo after 1–2 weeks (24-26); tricyclics do so after 3–4 weeks (4). In the current study sertraline demonstrated significant efficacy somewhat sooner than has been reported for the tricyclics—by week 3 for the primary outcome measure of major panic attacks. By week 2, 61% of the patients had achieved a 50% reduction in the weekly number of panic attacks. In the sertraline treatment group there was no attrition in the first 3 weeks because of lack of efficacy, suggesting that, despite the initial severity of the disorder in this patient group and the high level of medical help seeking among panic patients in general, the improvement was sufficiently rapid.

High rates of response to placebo are frequently found in panic treatment studies, around 50% according to a recent review (27). This makes it especially difficult to demonstrate efficacy in short-term treatment studies of panic disorder. The 46% placebo response observed at endpoint in the current study is consistent with this finding. At least one naturalistic follow-up of placebo responders in a panic disorder treatment trial (28) demonstrated that most of these patients eventually begin medication treatment. This is consistent with the recurrent course of panic disorder (29).

Tolerability of Sertraline

Overall, the patients tolerated sertraline well; only 9% dropped out of treatment because of side effects. The side effects of sertraline in this study were similar to those reported in studies of sertraline for depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. A clinically relevant complication frequently reported during treatment of panic disorder with antidepressants is a jitteriness syndrome, consisting of adrenergic symptoms such as nervousness, sweating, and tremor (2). The jitteriness syndrome has been observed to occur in the first 2–3 weeks of treatment with both tricyclics (2, 3) and fluoxetine (30), and it may lead to medication discontinuation.

In the current study, the patients taking sertraline did not report the presence of a jitteriness syndrome during the initial 3 weeks of treatment, and only two sertraline-treated patients discontinued treatment because of any adverse experiences during the first week of treatment, neither of which was compatible with jitteriness. The absence of a jitteriness syndrome in our patients may have been due to the use of a low starting dose (25 mg/day) in our study during the initial week of treatment.

In conclusion, sertraline appears to be a safe, well-tolerated, and highly effective treatment for panic disorder. Therapeutic response occurs relatively rapidly and without notable risk of jitteriness with a 25-mg starting dose. The effective dose appears to be in the range of 50–200 mg/day. Sertraline treatment resulted in significant reductions in symptom severity in many clinically relevant dimensions of panic, including quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Principal investigators in the study were as follows: Barry S. Baumel, M.D., Baumel-Eisner Neuromedical Institute, Miami Beach, Fla.; Robert J. Bielski, M.D., Institute for Health Studies, Okemos, Mich.; John S. Carman, M.D., Psychiatry and Research, P.C., Atlanta; Wayne K. Goodman, M.D., University of Florida, Gainesville; Mark T. Hegel, Ph.D., Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.; Carl A. Houck, M.D., UAB Clinical Research, Birmingham, Ala.; Robert D. Linden, M.D., Pharmacology Research Institute, Long Beach, Calif.; Bharat Nakra, M.D., St. Louis Children’s Hospital Health Center, Chesterfield, Mo.; Kay Y. Ota, Ph.D., Friends Health Services Research Unit, Owings Mills, Md.; and Robert B. Pohl, M.D., Wayne State University, Detroit.

Received April 14, 1997; revisions received Dec. 9, 1997, and March 3, 1998; accepted April 15, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University, Detroit; and Pfizer, Inc.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wolkow, Central Research Division, Pfizer, Inc., 235 East 42nd St., New York, NY 10017-5755; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Pfizer, Inc.

|

1. Roy-Byrne P, Wingerson D, Cowley D, Dager S: Psychopharmacologic treatment of panic, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1993; 16:719–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Pohl R, Yeragani VK, Balon R, Lycaki H: The jitteriness syndrome in panic disorder patients treated with antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:100–104Medline, Google Scholar

3. Noyes R Jr, Garvey MJ, Cook BL, Samuelson L: Problems with tricyclic antidepressant use in patients with panic disorder or agoraphobia: results of a naturalistic follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50:163–169Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schweizer E, Rickels K, Weiss S, Zavodnick S: Maintenance drug treatment of panic disorder, I: results of a prospective, placebo-controlled comparison of alprazolam and imipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:51–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Jobson KO, Davidson JR, Lydiard RB, McCann UD, Pollack MH, Rosenbaum JF: Algorithm for the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:483–485Medline, Google Scholar

6. den Boer JA, Westenberg HG, De Leeuw AS, van Vliet IM: Biological dissection of anxiety disorders: the clinical role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with particular reference to fluvoxamine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 9(suppl 4):47–52Google Scholar

7. Hoehn-Saric R, McLeod DR, Hipsley PA: Effect of fluvoxamine on panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:321–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W, Gabel J: A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:44–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bakish D, Hooper CL, Filteau MJ, Charbonneau Y, Fraser G, West DL, Thibaudeau C, Raine D: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial comparing fluvoxamine and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:135–141Medline, Google Scholar

10. Oehrberg S, Christiansen PE, Behnke K, Borup AL, Severin B, Soegaard J, Calberg H, Judge R, Ohrstrom JK, Manniche PM: Paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:374–379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lecrubier Y, Bakker A, Dunbar G, Judge R: A comparison of paroxetine, clomipramine and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder: Collaborative Paroxetine Panic Study Investigators. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:145–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Reimherr FW, Chouinard G, Cohn CK, Cole JO, Itil TM, LaPierre YD, Masco HL, Mendels J: Antidepressant efficacy of sertraline: a double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl B):18–27Google Scholar

13. Greist J, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, Liebowitz M, Lydiard RB, Rasmussen S, White K: Double-blind parallel comparison of three dosages of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:289–295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gupta MA, Gupta AK: Chronic idiopathic urticaria associated with panic disorder: a syndrome responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants? Cutis 1995; 56:53–54Google Scholar

15. Papp LA, Weiss JR, Greenberg HE, Rifkin A, Scharf SM, Gorman JM, Klein DF: Sertraline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety and mood disorders (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1531Medline, Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1989Google Scholar

17. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Grebb JA: Psychiatric rating scales, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 5th ed, vol 1. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, pp 544–545Google Scholar

20. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 217–222Google Scholar

21. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Medline, Google Scholar

22. Shear K, Sholomskas D, Cloitre M: MC-PAS: The Multicenter-Panic Anxiety Scale. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, 1992Google Scholar

23. Shear MK, Maser JD: Standardized assessment for panic disorder research: a conference report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:346–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Ballenger JC, Burrows GD, DuPont RL Jr, Lesser IM, Noyes R Jr, Pecknold JC, Rifkin A, Swinson RP: Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: results from a multicenter trial, I: efficacy in short-term treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:413–422Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lydiard RB, Lesser IM, Ballenger JC, Rubin RT, Laraia M, DuPont R: A fixed-dose study of alprazolam 2 mg, alprazolam 6 mg, and placebo in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12:96–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Schweizer E, Patterson W, Rickels K, Rosenthal M: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a once-a-day, sustained-release preparation of alprazolam for the treatment of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1210–1215Link, Google Scholar

26. Hirschfeld RMA: Placebo response in the treatment of panic disorder. Bull Menninger Clin 1996; 60(suppl A):A76–A86Google Scholar

27. Pollack MH, Otto MW, Tesar GE, Cohen LS, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF: Long-term outcome after acute treatment with alprazolam or clonazepam for panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:257–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Keller MB, Hanks DL: Course and outcome in panic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1993; 17:551–570Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gorman JM, Liebowitz MR, Fyer AJ, Goetz D, Campeas RB, Fyer MR, Davies SO, Klein DF: An open trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of panic attacks. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:329–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar