Private Psychotherapy Patients of Psychiatrist Psychoanalysts

Abstract

Objective:The characteristics of private psychotherapy patients of medical psychoanalysts are described. Method:A structured interview was administered to 51 medical psychoanalysts. Patients’ demographic characteristics, historical features, and other clinically relevant aspects of behavior were assessed.Results:Of 575 patients, 88% had at least one axis I disorder and 46% had at least one axis I and one axis II disorder. Treatment duration varied from less than 6 months to more than 6 years. Forty-three percent of the patients were also treated with psychotropic drugs.Conclusions:The patients in this cohort met the criteria for DSM-IV psychiatric disorders, had lifetime histories of major psychiatric disturbances, and were not the “worried well.” Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1772-1774

Numerous studies indicate that psychotherapy is efficacious (1). It is difficult to validly generalize from these to the treatment of actual patients in the community, however. One reason for this is that patients with multiple psychiatric disorders or both psychiatric and physical disorders, common in actual practice, are often excluded from research protocols (2,3).

Generalizations based on efficacy research have nonetheless influenced the insurance industry, particularly in its practices regarding treatment dose. They have also influenced the way many contemporary clinicians conceptualize psychopathology (4, 5). There has been increasing emphasis on managing psychiatric symptoms rather than treating psychiatric patients.

Two investigations (2,6) suggest that it is useful to study psychotherapy naturalistically. A questionnaire administered to psychotherapy consumers revealed that most had received substantial assistance (2). The longer the treatment lasted, the better the results were likely to be. Since the data were self-report only, many clinically relevant behavioral dimensions were not assessed.

Psychoanalytic patients in Canada, the subjects of another study (6), were found to suffer from multiple psychiatric disorders, and many had histories of trauma. Relatively few patients were treated with formal psychoanalysis, however.

Psychodynamically oriented psychotherapies have been little studied as they are actually practiced. Even the most basic information about private psychotherapy patients remains to be systematically reported.

The present investigation was carried out to determine the feasibility of collecting information from therapists about their private patients. If feasible, we also planned to describe the clinical characteristics of their patients.

METHOD

The protocol for this study was approved by the governing body (Council) of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, and therapists were recruited from the membership of the academy. It was explained at scientific meetings of the academy that a descriptive study of clinical practice was being carried out. Volunteers were requested, and participants were chosen to provide a convenience sample. Only one subject who was solicited refused to participate.

Therapists were asked to provide information on all of their patients who were at least 18 years of age, seen to date for a minimum of four sessions, and presently being treated with (continuous) psychotherapy at least once per week. A total of 575 patients were covered between 1993 and 1995, an average of 11.5 patients (SD=7.4) per therapist. All therapists reported on their entire practice as specified, with the exception of two for whom data collection was suspended for personal reasons; these therapists contributed a total of only five patients to the total group.

A structured interview was administered to each therapist by graduate students under the supervision of two of us (R.C.F., W.B.). Patients’ demographic characteristics, historical features, and other clinically relevant aspects of behavior were assessed.

Use of psychotropic drugs was documented for patients who had received such medication daily for a minimum of 2 weeks during the present treatment. Drug use was considered absent if psychotropic drugs were administered exclusively on an as-needed basis. The categories of drugs that were specified were neuroleptics, antidepressants, antimanic agents, minor tranquilizers, sedatives, and hypnotics. A “miscellaneous” category was also included for other agents.

The interviews were carried out by graduate students under supervision. Approximately 50% of the interviews were conducted in the therapists’ offices, a few were performed at national meetings, and the rest were done by telephone. Written informed consent was obtained from the therapists after the procedure was fully explained. The patient data were entirely anonymous and are reported for aggregates only. The study was presented as being descriptive. No hypotheses were advanced.

RESULTS

The therapist study group included 35 men, who had an average age of 65 years (SD=12) and had been in practice for an average of 27 years (SD=11), and 16 women, who had an average age of 58 years (SD=9) and had been in practice for an average of 20 years (SD=9). They were Caucasian, except for two Asian American men.

Of the 51 therapists, 43 practiced in the New York metropolitan area; the others practiced in Hartford, Conn.; Tucson, Ariz.; Seattle; Washington, D.C.; Baltimore; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Dallas; and Los Angeles.

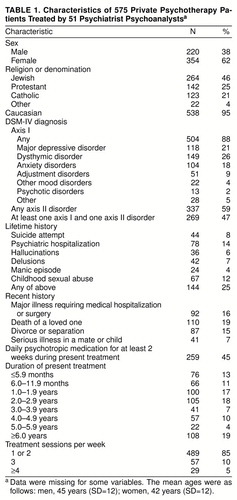

Approximately 60% of the patients were women. Religion and other characteristics are shown in table 1. The patients tended to be highly educated and of the upper middle class.

Most of the patients had at least one axis I disorder. Their DSM-IV axis I diagnoses are shown in table 1. More than one-half had at least one axis II disorder, and just under one-half had at least one axis I and one axis II disorder simultaneously.

Lifetime rates of attempted suicide, psychiatric hospitalization, hallucinations, delusions, manic episodes, and childhood sexual abuse were each less than 15%, but 25% of all patients had had at least one of the preceding experiences (table 1).

Major illness requiring medical hospitalization or surgery, the death of a loved one, and divorce or separation had each been experienced by about 15% of the patients during the present treatment, and 7% had a mate or child with serious illness (table 1).

Just under one-half of the patients received psychotropic medication for at least 2 weeks during the present episode of treatment. Factors associated with the use of medication included ever having been psychiatrically hospitalized, ever having attempted suicide, ever experiencing a manic episode, hallucinations, or delusions, and a present diagnosis of major depressive disorder, single episode or recurrent.

Most of the patients were seen once or twice per week. Neither stressful life events during the present treatment nor duration of treatment was associated with psychotropic drug use.

DISCUSSION

Psychiatrist psychoanalysts willingly provided data about their private psychotherapy patients, indicating that this type of naturalistic investigation is feasible. The patients studied in this investigation appear similar to the psychoanalytic patients described by Doidge et al. (6) and are clearly not the “worried well.” Psychotherapy patients treated for more than 2 years have not previously been described, to the best of our knowledge. They constituted 58% of our study group, and we are preparing another report on them.

We found, as others have, that although many psychotherapy patients receive psychotropic medication, many do not (7). Patients often receive medication on an as-needed basis. We did not rate these patients “positive” for pharmacotherapy. On the other hand, we intentionally selected a brief period of daily medication use as indicating use of medication, far less than is required for adequate treatment as a general rule. We selected the 2-week criterion in order to be conservative—i.e., the patients did not receive medication even for the relatively brief period of 2 weeks.

Serious medical illnesses were experienced by 14% of the patients during the current episode of psychotherapy, and most of these patients were treated with many more psychotherapy sessions than would be approved by most managed care providers. For example, of patients in treatment for 2.0 years or longer, 26% experienced serious medical illnesses. Of patients with serious medical illnesses, 64% were in treatment for 2.0 years or longer. Although we did not study cost-effectiveness, others have observed that psychiatric patients with medical illnesses who receive psychotherapy spend less for medical treatment than patients with psychiatric and medical illnesses who do not receive psychotherapy (8).

The patients in this study were not part of managed care plans. More and more people are purchasing psychotherapy through such plans, however. Patients with similar clinical histories are often subject today to limits on funding for psychotherapy that extends beyond 15–20 sessions. Insurance companies have been able to equate absence of demonstrated effectiveness of long-term psychotherapy with proof of absence of positive effects.

In demonstrating the feasibility of collecting such a study group, we hope to have taken an important first step toward subsequent naturalistic studies that include outcome.

The generalizability of our findings is limited by the atypically high socioeconomic status of our patients, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity, and the fact that all of the therapists were experienced psychiatrist psychoanalysts who were not selected randomly. We did not study patients who dropped out of treatment before our collection of data, but we plan to do so.

Received July 7, 1997; revision received June 29, 1998; accepted July 16, 1998. From the American Academy of Psychoanalysis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Friedman, Apt. 103, 225 Central Park West, New York, NY 10024; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, the Glass Institute for Basic Psychoanalytic Research, and the American Association of Private Practice Psychiatrists.The authors thank Vida S. Grayson, C.S.W., for assistance with all phases of this study.

|

1. Doidge N: Empirical evidence for the efficacy of psychoanalytic psychotherapies and psychoanalysis: an overview. Psychoanalytic Inquiry 1997; 17:102–150Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Seligman MEP: The effectiveness of psychotherapy: the Consumer Reports study. Am Psychol 1995; 50:965–974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Miller NE, Luborsky L, Barber JP, Docherty JP (eds): Psychodynamic Treatment Research: A Handbook for Clinical Practice. New York, Basic Books, 1993Google Scholar

4. Hall RCW: Social and legal implications of managed care in psychiatry. Psychosomatics 1994; 35:150–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gabbard GO: The big chill. Acad Psychiatry 1992; 16:119–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Doidge N, Simon B, Gillies LA, Ruskin R: Characteristics of psychoanalytic patients under a nationalized health plan: DSM-III-R diagnoses, previous treatment, and childhood trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:586–590Link, Google Scholar

7. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States, I: volume, costs, and user characteristics. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1281–1288Link, Google Scholar

8. Lazar SG: Epidemiology of mental illness in the United States: an overview of the cost effectiveness of psychotherapy for certain patient populations. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 1997; 17:4–16Crossref, Google Scholar