Limitations of Axis II in Diagnosing Personality Pathology in Clinical Practice

Abstract

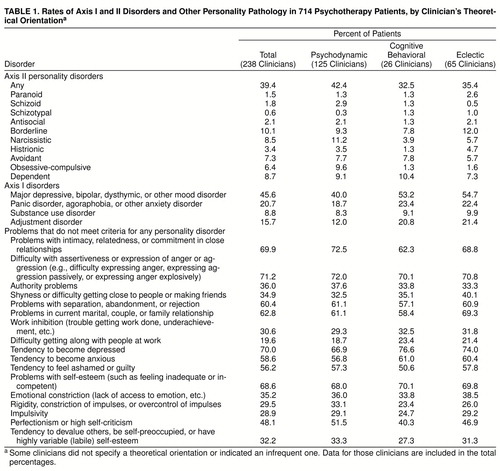

Objective:DSM-IV’s axis II is limited to severe personality disturbances, posing difficulty for diagnosing less severe but nonetheless clinically significant personality pathology. The authors examined the percentage of patients treated in clinical practice for personality pathology who are diagnosable with DSM-IV. Method:Psychiatrists and psychologists from a random national sample provided diagnostic data on 714 patients treated for enduring, maladaptive personality patterns.Results:Only 39.4% of the patients had diagnosable axis II disorders. This percentage was relatively stable across clinicians’ theoretical orientations and did not vary substantially when axis I diagnosis was controlled for.Conclusions:DSM-IV cannot be used to diagnose most patients being treated for personality problems. The range of axis II should be broadened to encompass the range of personality pathology seen in clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1767-1771

Clinical observation suggests that much of the personality pathology clinicians see and treat in practice may not be captured by axis II of DSM-IV (1, 2). Personality refers to enduring patterns of cognition, emotion, motivation, and behavior that are activated in particular circumstances (see references 3–5). A persistent but nondebilitating maladaptive pattern of thought, feeling, motivation, or behavior may command substantial, and appropriate, clinical attention, but because it does not cross a high threshold, it is often undiagnosable. Nothing guarantees that problems such as difficulties with authority figures or intimate attachment relationships can always be understood as subclinical manifestations of one of the current 10 axis II disorders or subsumed by axis I categories.

For example, a person with clinically significant rejection sensitivity or abandonment fears may or may not be accurately described as having “borderline features,” although this is the only way such a problem can be diagnosed by using DSM-IV. The literature on adult attachment (see, for instance, references 6 and 7) suggests that abandonment fears are prominent in many individuals without other borderline symptoms, for whom a description of “borderline features” would be misleading. Other clinically significant personality problems, such as difficulty in committing oneself to relationships, repeatedly choosing relationships that are unsatisfying, or chronically feeling guilty or being perfectionistic, do not bear an obvious relation to any axis II (or axis I) disorder.

As part of a larger study, one of us (D.W.) recently surveyed a group of experienced clinicians at Harvard Medical School, asking whether they were currently treating patients for “neurotic” personality patterns that could not be diagnosed on axis II (2). Of this group, 86.5% reported that they did, and in free-response format they described an array of patterns, such as difficulty with self-esteem, authority problems, difficulties with peers, and difficulties in intimate relationships. The data from this pilot study are suggestive, but they reflect a small study group that may not be representative and they leave many questions unanswered. The present study was designed to extend these findings by 1) using a large, representative national sample of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists; 2) ascertaining the percentage of patients these clinicians treat for personality pathology who can or cannot be diagnosed by using axis II; 3) examining the nature and prevalence of the personality patterns not on axis II that clinicians report observing and treating; 4) controlling for theoretical orientation, since adherents of some theoretical perspectives may be more likely to look for or address personality pathology that proponents of other perspectives might not find compelling or meaningful; and 5) controlling for axis I diagnosis, since personality pathology not diagnosable on axis II might be diagnosable on axis I.

METHOD

As part of a broader program of research in which clinicians are providing data to help refine axis II categories, criteria, and diagnostic procedures (8,9), we contacted 7,000 clinicians from the registers of the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association. Of the contacted clinicians, 2,400 indicated a willingness to participate in future studies. These respondents were a highly experienced group: the mean time since residency or postdoctoral training was 18.18 years (SD=9.56, range=1–50). Several had multiple institutional affiliations: 32.7% worked in hospitals at least part-time, 20.5% worked in outpatient clinics, 83.9% had private practices, and 11.4% worked in forensic settings. When asked about primary theoretical orientation, responses were as follows: psychodynamic or psychoanalytic, 44.8%; cognitive behavioral, 16.1%; biological or systemic, 4.9%; and eclectic, 34.2%.

For the present study, we surveyed 800 randomly selected clinicians from this sample of 2,400. Each participant was asked to describe the last three nonpsychotic adult patients he or she had seen before completing the form who were being treated with psychotherapy “for enduring patterns of thought, feeling, motivation, or behavior that are dysfunctional or lead to distress. Their personality problems may or may not be serious enough to qualify for a personality disorder diagnosis.” The clinicians were then instructed to mark an “X” on a grid next to any of the problems or diagnoses they considered “present and clinically significant.”

The grid consisted of a checklist including 1) all of the personality disorders from DSM-IV; 2) four prevalent axis I categories potentially related to personality pathology (mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and adjustment disorders); and 3) a list of problems that do not necessarily meet the criteria for any personality disorder—including problems with intimacy, emotional constriction, impulsivity, and problems with self-esteem—derived from prior free-response survey responses. The complete list of diagnoses and problems is shown in table 1. We asked the participants to describe the last three patients each of them had seen, to avoid biases in patient selection, and we chose a relatively theory-neutral definition of personality pathology (enduring, maladaptive patterns of thought, feeling, motivation, and behavior). We specified patients treated with psychotherapy for these problems to avoid the possibility that the respondents would describe state rather than trait disorders, which could have produced an artifactual underdiagnosis of axis II conditions (for example, if they considered any patient treated with antidepressants to have personality pathology). We specified that the problem must be present and clinically significant (requiring clinical attention), in an effort to guarantee that the clinicians’ thresholds for reporting non-axis-II personality pathology would not be too low.

RESULTS

The 238 responding clinicians (29.8% response rate) described a total of 714 patients. Of the 236 who indicated their professional status, 36.4% were psychiatrists and 63.6% were psychologists. Table 1 presents the major findings for the entire sample, indicating the percentage of patients diagnosed with any personality disorder, with each of the current axis II personality disorders, with the axis I disorders that could present potential confounds, and with specific personality problems not currently represented on axis II. We also analyzed the data by stratifying according to the clinicians’ theoretical orientations.

As can be seen from the table, only 39.4% of the overall sample were diagnosed with personality disorders. (This percentage did not vary by clinician’s degree: M.D., 35.2%; Ph.D., 38.3%.) As can be seen from the table, this figure was relatively consistent across therapists’ theoretical orientations as well. To minimize the potential influence of rater variance on the findings (that is, to ensure that a small number of clinicians did not bias the findings in either direction by over- or underreporting personality disorders), we performed three secondary analyses, independently assessing the frequency of personality disorders for the first, second, and third patients described by each clinician. Rater variance had minimal effect: for psychodynamic clinicians, the percentage of patients with personality disorders ranged from 38.4% to 45.6%; for cognitive behavioral clinicians, 30.8% to 34.6%; and for eclectic clinicians, 33.3% to 37.5%.

The same consistency across theoretical orientations is apparent for non-axis-II personality problems, the most common of which were difficulties with intimacy and commitment; assertiveness, anger, or aggression; separation, abandonment, or rejection; current couple, family, or marital relationships; persistent patterns of depressive and anxious symptoms that do not necessarily meet axis I criteria; and problems with self-esteem. Over one-half of the items on the list of personality problems not in axis II were individually more prevalent than all axis II disorders combined.

Next, we compared patients with and without comorbid axis I conditions, to see whether the presence of axis I disorders accounted for the large percentage of patients without axis II diagnoses. Axis I diagnosis had only a limited impact. Among patients with comorbid mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and adjustment disorders, the percentages of patients with personality disorder diagnoses were 40.6%, 50.7%, 57.1%, and 25.0%, respectively. For patients without these comorbid axis I conditions, the percentages were 38.4%, 36.5%, 37.7%, and 42.1%, respectively. These data suggest that axis I cannot account for the roughly one-half of patients with personality pathology who cannot be diagnosed on axis II. Of particular interest are the data on mood disorders, which were highly prevalent in the sample (45.6%) and could potentially have accounted for some of the pathological personality patterns the clinicians endorsed. This was not, however, the case. Except for the tendency to experience sadness, anxiety, shyness, and low self-esteem, the frequency of both axis II disorders and personality problems not represented on axis II differed little between patients with and without mood disorders.

Finally, we compared the data for patients with and without axis II diagnoses. Not surprisingly, patients without personality disorders were described as having fewer of the problems listed than those with axis II diagnoses. The patients with axis II diagnoses had more problems with intimacy, authority problems, difficulty in peer relationships, work inhibition, conflict with co-workers, impulsivity, and narcissistic trends than those without personality disorders.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the multiaxial system in DSM-IV is to provide a “comprehensive and systematic evaluation” of the patient’s pathology that includes information “that might be overlooked if the focus were on assessing a single presenting problem” (p. 25). This is an important and clinically useful goal. Our data suggest, however, that attainment of this goal has been hindered by the inadequacy of axis II in assessing the broad range of personality problems for which patients seek treatment and that clinicians report addressing. Although the methods used in this study were simple and straightforward, the findings document a substantial gulf between clinical practice and the diagnostic manual designed to inform it: The majority of patients with personality pathology significant enough to warrant clinical psychotherapeutic attention (60.6%) are currently undiagnosable on axis II. Neither the clinician’s theoretical orientation nor the presence of any axis I condition (conservatively including even dysthymia, which is arguably a trait rather than state disturbance) influenced the findings.

One could raise several potential objections to this study, the most important of which is that clinicians’ diagnoses may be unreliable. Several considerations, however, limit this concern. First, findings across theoretical orientations were almost identical. It would be hard to imagine that if clinicians are making gross diagnostic errors (in particular, if they are dramatically underdiagnosing axis II disorders), that they are doing so in equal numbers in every theoretical orientation, when some theories (such as psychoanalysis) focus more heavily on personality patterns not reflected in axis II. The descriptions of patients from clinicians with the three most prevalent theoretical orientations in the sample can be considered three separate groups that converge on the same findings; so, too, can the findings for the first, second, and third patient described by each clinician. Second, the findings were nearly identical for psychologists and psychiatrists. Given the substantial differences in their training, it is again difficult to imagine that each group independently is making the same errors of underdiagnosis. Third, the relative prevalence rates for the individual axis II diagnoses provided by the clinicians in this sample for patients diagnosed with axis II disorders were similar to the results of epidemiological studies of personality disorders (e.g., 1.4% schizotypal versus 21.6% borderline). Fourth, the participants in this study were experienced clinicians, with an average of over 18 years of clinical experience. If even seasoned clinicians cannot use DSM-IV with some degree of accuracy in diagnosing severe personality pathology, then the diagnostic manual is even more problematic than we are suggesting. Finally, there is no reason to assume that the respondents to this study would systematically under- rather than overdiagnose personality pathology. The more likely possibility is the opposite—that given their familiarity with DSM-IV, they would fail to recognize personality pathology that cannot be readily categorized by using the current diagnostic system.

A second objection is that perhaps most personality pathology would be diagnosed by clinicians as personality disorder not otherwise specified. Two factors, however, limit this objection. First, patients without personality disorders in this sample were clearly healthier than patients with personality disorders on most dimensions. Thus, the absence of a personality disorder diagnosis was not likely to reflect simply the clinician’s inability to find a personality disorder category that fit the data. Second, even if the patients not currently covered by existing axis II categories could be diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified, that would mean that the majority of patients with personality disorders have to be placed into a nondescript residual category that conveys no information about their personality characteristics. Either way, new categories or dimensions need to be defined in order to classify the 60.6% of patients who do not fit into any of the current categories.

Finally, one could argue that a 29.8% response rate might have led to an unrepresentative sample. Because the participants were unpaid, however, the response rate seems reasonable, given the many constraints on the time of experienced professionals. Further, any systematic bias in the sample would likely have led to a conservative bias for the present taxonomy since clinicians interested enough in personality pathology to complete the survey would be more likely to over- rather than underdiagnose axis II disorders.

Axis II could potentially be amended in one of three ways to increase its comprehensiveness. The first is simply to include additional categories to reflect less severe personality disturbances (e.g., depressive personality style, obsessional style, hysterical style, impulsive style, emotionally constricted style), selected empirically through procedures such as cluster analysis (9). A second is to replace the current categorical system with a dimensional system, either derived from factor analysis, as several researchers have advocated (10–13), or by using Likert ratings (e.g., on a 1–7 scale) of the existing personality disorders plus additional dimensions of personality pathology not currently represented on axis II (for instance, a patient might be rated as 7 on borderline, 4 on histrionic, and so forth).

A third possibility is to replace or supplement axis II with a functional assessment of personality. A functional assessment is essentially a case formulation, which addresses the relevant domains of personality functioning. The categorical approach in DSM-IV and the dimensional approaches currently being proposed pose diagnostic questions of the form “Does the patient cross the threshold for narcissistic personality disorder?” or “How low is the patient on the trait of agreeableness?” A functional assessment, in contrast, asks, “Under what circumstances are which dysfunctional cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral patterns likely to occur?” Thus, instead of primarily asking whether a person can be categorized as extremely narcissistic or disagreeable, this approach asks a series of questions such as, “Is the patient vulnerable to feeling ashamed and humiliated? Does this happen primarily with peers, authority figures, or romantic relationships? Does the patient respond to shame or humiliation by defensively devaluing others, by devaluing the self, or both?” This approach is clinically useful, is compatible with either categorical or dimensional diagnoses, and can be assessed reliably by using diagnostic methods that mirror the way clinicians diagnose personality in practice (8, 14).

Received Nov. 19, 1997; revisions received March 5 and June 5, 1998; accepted June 26, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and the Cambridge Hospital/Cambridge Health Alliance. Address reprint requests to Dr. Drew Westen, Department of Psychiatry, The Cambridge Hospital, 1493 Cambridge St., Cambridge, MA 02139; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

1. Gabbard GO: Finding the “person” in personality disorders (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:891–893Link, Google Scholar

2. Westen D: Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:895–903Link, Google Scholar

3. Mischel W, Shoda Y: A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol Rev 1995; 102:246–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Westen D: Self and Society: Narcissism, Collectivism, and the Development of Morals. New York, Cambridge University Press,1985Google Scholar

5. Westen D: A clinical-empirical model of personality: life after the Mischelian ice age and the NEO-lithic era. J Pers 1995; 63:495–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J: Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: a move to the level of representation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 1985; 50:67–104Crossref, Google Scholar

7. von IJzendoorn M: Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: a meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychol Bull 1995; 117:387–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, I: developing a clinically and empirically valid assessment method. Am J Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

9. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, II: toward an empirically based and clinically useful classification of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

10. Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Schroeder ML, Irish S: Convergence of two systems for assessing specific traits of personality disorder. Psychol Assessment 1996; 8:294–303Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Costa P, Widiger T (eds): Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994Google Scholar

12. Widiger T, Frances A: Towards a dimensional model for the personality disorders, in Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Edited by Costa P, Widiger T. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994, pp 19–39Google Scholar

13. Widiger T, Sanderson C: Toward a dimensional model of personality disorders, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 433–458Google Scholar

14. Westen D: Case formulation and personality diagnosis: two processes or one? in Making Diagnoses Meaningful. Edited by Barron J. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association Press, 1998Google Scholar