Anxiety Disorders Among African-American and White Primary Medical Care Patients

Abstract

The prevalence of current anxiety disorders and associated clinical patterns was examined in a sample of 125 African American and 120 white primary medical care patients between ages 18 and 64. Patients who indicated they had at least one mood or anxiety symptom in response to a screening questionnaire were interviewed to determine the presence of a DSM-IV anxiety, mood, or possible alcohol abuse disorder. Demographic data and data on mental- and physical-health-related functioning and health service utilization were also collected. The authors found no racial differences in the proportions of patients who met DSM-IV criteria for the disorders, nor in their symptom patterns, level of functional disability, or rates of health and mental health service utilization.

Research addressing the etiology, assessment, and treatment of anxiety disorders has proliferated in the past two decades. However, little information is available on the prevalence and characteristics of anxiety disorders among African Americans. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study of the National Institute of Mental Health determined that the lifetime prevalence of simple phobia was significantly higher among African Americans than among any other group (1) and that African Americans had a higher lifetime prevalence of agoraphobia than whites (2). However, no racial differences were evident in the prevalence of panic disorder in the ECA study (3). More recently, the National Comorbidity Survey (4) found no racial differences in the prevalence of any anxiety disorder.

Although these studies obtained similar rates of anxiety disorders among African Americans and whites for some anxiety disorders, investigators have suggested that racial differences in help-seeking patterns and symptom presentation may produce underrecognition and misdiagnosis of anxiety disorders among African Americans presenting in psychiatric outpatient settings (5). Furthermore, compared with whites, depressed African-American primary medical care patients report more severe somatic symptoms and a different pattern of psychiatric comorbidity, including more panic disorder (6).

In reviewing anxiety disorders research with African Americans, Neal and Turner (7) found higher rates of panic disorder to be associated with isolated sleep paralysis or hypertension. Neither has been associated with panic disorder in whites. Although these studies address the prevalence and nature of anxiety among African Americans, they do not analyze possible racial differences in rates of specific anxiety disorders.

Racial differences in psychiatric help-seeking patterns have been documented (8), with African Americans more likely than whites to seek treatment in general medical rather than mental health specialty settings. This pattern suggests the need to examine possible racial differences in the rates or clinical presentation of anxiety disorders in the primary care sector. To address this issue, we investigated the prevalence of current anxiety disorders, symptom patterns, functional impairment, and health service utilization of African Americans and whites in this sector.

Methods

Participants

Subjects between ages 18 and 64 were recruited in primary medical care settings in Pittsburgh. They were informed that the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine was studying the nature of anxiety among general medical outpatients. Written informed consent was sought for a two-phase assessment protocol that had been approved by the university's institutional review board.

This study used a modified Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Patient Questionnaire (PRIME-MD PQ) and Clinician Evaluation Guide (PRIME-MD CEG). The original PRIME-MD (9) assessed panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, eating disorders, mood disorders, and somatoform disorders and screened for possible alcohol abuse and possible bipolar disorder. We expanded the PRIME-MD PQ and CEG to screen for and assess additional DSM-IV anxiety disorders such as agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Patients who indicated that they had experienced at least one anxiety or mood symptom on the PRIME-MD PQ were asked to continue with a second assessment. During the second assessment, trained research assistants evaluated patients using the PRIME-MD CEG. The patients also completed the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) (10), which evaluates functioning related to mental and physical health, and they answered questions about demographic characteristics and health service utilization.

Statistical analyses

Chi square tests were used to analyze categorical variables, and t tests were used with continuous data. Racial differences in symptom patterns for mood and anxiety disorders were examined through tests comparing whites and African Americans on the total number of symptoms identified. Chi square tests were used to compare the proportions of African-American patients and white patients who met specific diagnostic criteria. Given the numerous analyses, an alpha of .003 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 552 patients completed the PRIME-MD PQ, and 480, or 87 percent, reported experiencing at least one symptom of depression or anxiety. Of these 480 symptomatic patients, 271 patients, or 56 percent, consented to the PRIME-MD CEG interview. This report focuses on 120 consenting patients who identified their racial identity as white (49 percent) and 125 consenting patients who identified themselves as black or African American (51 percent).

Participants of both races were predominantly female (74 percent), unmarried (76 percent), and unemployed (64 percent), Most had at least a high school education (81 percent). The mean±SD age of participants was 36.7±11 years.

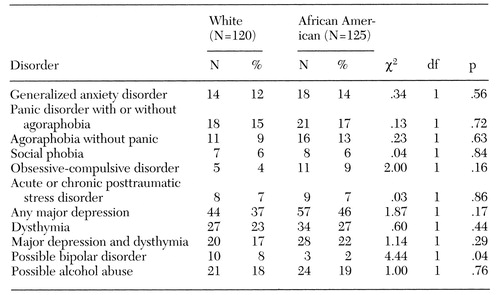

No racial differences were found in the distribution of specific anxiety, mood, or possible alcohol abuse disorders (see Table 1). African Americans and whites also did not differ in the number of symptoms of panic, mood, generalized anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder they reported having experienced, nor were race-specific differences found in the proportion of patients who met specific criteria for each of the anxiety disorders assessed.

Analysis of data from the eight SF-36 subscales similarly indicated no racial differences in functioning related to mental health or physical health. However, compared with national norms, participants with anxiety disorders reported diminished vitality, poorer mental health, and greater functional limitations due to mental health problems.

Similar proportions of African Americans and whites sought help for a health problem (99 percent and 98 percent, respectively) or made mental health visits (19 percent and 29 percent, respectively) in the six months before the assessment. No racial differences were found in the number of health or mental health visits in that time period.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of anxiety disorders and associated clinical factors in a sample of African-American and white primary medical care patients. Several methodological limitations warrant attention. Although the PRIME-MD has demonstrated reliability and validity (9), our modified version with additional DSM-IV anxiety disorders has not been validated. The interviewers were trained by experienced clinicians (MKS and MJM) and were supervised weekly, but diagnostic interrater reliability was not established.

Our analyses also lack data on psychiatric symptom severity or medical comorbidity, which may differ by race or diagnostic status. Finally, our results may be biased by patient self-selection, because 44 percent of the patients who reported having experienced at least one mood or anxiety symptom did not complete the PRIME-MD CEG. However, prior research in the same health centers using similar recruitment strategies found no racial differences in the proportion of patients consenting to a diagnostic assessment (6).1

Despite these methodological constraints, our results are consistent with recent epidemiological data indicating no racial differences in the prevalence of anxiety disorders (5). The two racial groups in our study also exhibited similar rates of comorbid major depression (approximately 45 percent). Although no racial differences were found in the number of mood, panic, generalized anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms indicated by the study participants, the absence of data limits our ability to fully address patterns of symptom severity. Both African-American and white individuals with anxiety disorders reported similar patterns of functional impairment, with vitality and mental-health-related functioning most adversely affected.

Our findings of no race-specific differences in utilization of specialty mental health services are consistent with those of the Baltimore ECA follow-up study (unpublished data, Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al, 1998). The follow-up study found initial underutilization of such services by African Americans compared with whites, but African Americans' use of mental health services increased over time and eliminated racial differences. Nevertheless, African Americans were more likely to discuss mental health problems in general medical settings without having seen a mental health specialist.

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders are equally prevalent among African-American and white primary medical care patients who also display similar patterns of functional disability. Few studies have examined rates of anxiety disorders among African Americans in the primary care sector. Despite our study's methodological limitations, it provides evidence that African Americans and whites are similarly affected by anxiety disorders and that similar proportions of each racial group seek mental health specialty treatment. Future studies of more diverse geographic areas and types of primary care practices should examine racial differences in symptom severity, associated medical comorbidity, and treatment attitudes to determine their impact on illness behavior and treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants MH-01328 to Dr. Brown and MH-45851 to Dr. Schulberg. The authors thank Deena R. Palenchar, M.S., for technical assistance.

Dr. Brown is assistant professor of psychiatry, Dr. Shear is professor of psychiatry, and Dr. Schulberg is professor of psychiatry, psychology, and medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O'Hara Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Madonia is behavioral science coordinator in the department of family medicine at Western Pennsylvania Hospital in Pittsburgh.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and substance abuse among 245 primary care patients, by race

1. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:949-958, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Blazer D, George LK, Landerman R, et al: Psychiatric disorders: a rural/urban comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:651-656, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Horwath E, Johnson J, Hornig CD: Epidemiology of panic disorder in African Americans. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:465-469, 1993Link, Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Paradis CM, Friedman S, Lazar RM, et al: Use of a structured interview to diagnose anxiety disorders in a minority population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:61-64, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ: Clinical presentations of major depression by African Americans and whites in primary medical care practice. Journal of Affective Disorders 41:181-191, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Neal AM, Turner SM: Anxiety disorders research with African Americans: current status. Psychological Bulletin 109:400-410, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford, DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Medical Care 32:15-24, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Spitzer R, Williams J, Kroenke K, et al: Utility of new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1,000 study. JAMA 272:1749-1756, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36):1. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473-483, 1992Google Scholar