Intensity and Continuity of Services and Functional Outcomes in the Rehabilitation of Persons With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The intensity and continuity of services delivered to individual clients in a community-based psychosocial rehabilitation program were examined in relationship to functional changes in the clients that occurred during the first 12 months of the program. METHODS: Subjects were 41 clients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were admitted to an intensive psychosocial rehabilitation program. Measures of clinical and psychosocial functioning were derived from client interviews administered at baseline and six and 12 months later. Measures of service intensity and continuity came from data gathered daily by staff over 12 months. RESULTS: The results supported the hypotheses that greater intensity and longitudinal continuity of services are related to more client improvement as indicated by reduced rates of hospitalization and improved psychosocial functioning after both six and 12 months. Although clients' symptom levels increased over time, a significant relationship was noted between service intensity and continuity and better symptom outcomes after 12 months. Multiple regression analyses indicated that an average of 22 percent, and as much as 28 percent, of the change in clinical and functional outcomes after 12 months of rehabilitation was explained by the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services. CONCLUSIONS: Clients who received more contact hours with staff and who had fewer gaps in service delivery achieved greater rehabilitative improvement in social, work, and independent-living domains and had fewer days of hospitalization. Based on these findings, clinicians, administrators, and researchers can assume that the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services are important to achieving rehabilitative outcomes in some community-based psychosocial rehabilitation models.

Community support programs vary in the types, form, and organization of the services they offer. They range from family-based psychoeducation or comprehensive psychosocial rehabilitation centers to assertive community treatment teams (1). Controlled studies on community-based care have consistently found that community support programs reduce hospitalization rates compared with usual community care (2,3,4,5,6,7,8).

On other psychosocial outcomes, community support programs have not been as consistent; they have been found to be either superior to or no better than usual care in promoting independent living and improving social or occupational functioning. In this regard, Olfson (4) has stated that the challenge for future research is to understand the conditions under which community support programs help clients achieve superior functional outcomes. A critical aspect of this effort concerns delineating the service delivery or program process variables that are related to client outcomes (6,9,10,11).

Continuity of care and intensity of service delivery are potentially critical ingredients in achieving positive client outcomes in community support programs. Although continuity of care has been widely discussed in the literature (10,12,13,14,15,16,17), Tessler and associates (18) have argued that the concept lacks a clear definition. Longitudinal continuity may be operationalized as the extent to which clients are involved in treatment continuously over time without gaps in service (10,17-19). Service intensity has been most commonly defined as the number of service contacts or the total duration of service contacts over a specified period (10,20,22).

Three studies relevant to longitudinal continuity have found that once the services of community support programs were terminated or attenuated, most of the functional gains made by clients during the intervention were lost (21,23,24). However, we are not aware of any studies that have investigated the impact of longitudinal continuity on client functional outcomes when they remain engaged in the intervention.

The relationship between service intensity and client outcomes has also received some attention. Snowden and Clancy (22) found that service intensity, defined as the number of service units consumed, was associated with better client outcomes at a community mental health center. Dietzen and Bond (20) evaluated the total frequency of case manager contact and outcome of subjects who had received a minimum of 12 months of assertive case management services at seven case management locations. The authors concluded that these programs must provide a minimum intensity of services to prevent hospital use.

In an investigation of two assertive case management models, Sands and Cnaan (25) found that subjects who received more contact and a greater number of services also achieved higher overall levels of functioning and were more compliant with medications. In a recent study comparing outcomes of clients in three community support programs that varied in critical service delivery characteristics, Brekke and colleagues (21) found that the intensity, specificity, and longitudinality of services were associated with superior functional outcomes in hospitalization and social, vocational, or independent-living domains.

Two important conclusions can be drawn from this literature. First, studies are needed on the relationship between longitudinal continuity and client outcomes when clients remain engaged in an ongoing intervention. Second, although the studies on service intensity generally suggest that more is better in terms of services, in all but one of these studies the program was the unit of analysis. Therefore, an important question that has not been addressed is whether program-level findings on service characteristics are reflected at the client level. Addressing this question, it cannot be assumed that because more intensive service programs are more effective than less intensive ones, individual clients who receive more intensive services will show greater functional change than those who receive less intensive services.

For example, even in an effective and intensive program, it is possible that lower-functioning clients will receive more services and achieve less rehabilitative gain than higher-functioning clients. Therefore, a complete understanding of the relationship between any service ingredients and client functional outcomes must include studies that use the client as the unit of analysis.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between the intensity and longitudinal continuity of community-based services received by individual clients and their prospective functional outcomes during 12 months in an intensive psychosocial rehabilitation program. It was hypothesized that the clients who experienced greater intensity and continuity of services would show higher levels of rehabilitative improvement on measures of clinical and functional outcomes.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects in this study were participants in a project that compared services and outcomes from three distinct models of community-based psychosocial intervention (21). In the parent study, which was conducted from 1989 to 1994, consecutive admissions were interviewed at program admission (baseline) and then every six months over a three-year period. The 41 subjects in this study were consecutive admissions to one of the treatment programs, called Portals, in the parent study.

To be included in this study, subjects had to remain at Portals for at least six months. Eleven of the 41 subjects left treatment after six months, and 30 remained in treatment for 12 months. We do not know whether these treatment terminations were planned or unplanned.

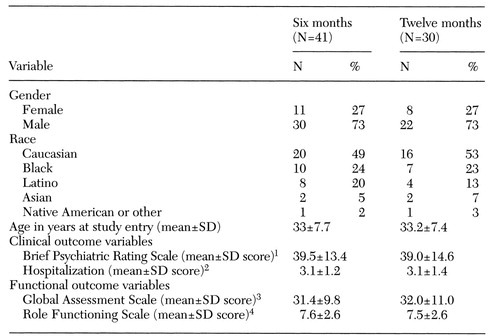

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and baseline functional levels of the study subjects. As can be seen, the subjects were predominantly males in their early 30s. The numbers of white and ethnic minority subjects were about equal. In regard to baseline levels of functioning, subjects were moderately symptomatic and had low levels of psychosocial functioning. No statistically significant differences between the six- and 12-months samples were found in demographic characteristics and baseline levels of functioning.

Diagnoses were established using chart data and a structured diagnostic interview, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (26), which is based on research diagnostic criteria (27). A more detailed description of the diagnostic procedures is available elsewhere (21). All subjects were diagnosed as having either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Program site

Portals provides a psychosocial rehabilitation clubhouse. It targets rehabilitative change in social, vocational, and independent-living functioning and has service continuums in each of these areas. Portals offers on-site psychiatric monitoring of medication for clients in the residential continuum and crisis management to prevent hospitalization for all clients. Services are ongoing in each of the continuums. Vocational services are available five days a week, and socialization services are available seven days a week and some evenings. In previous comparative analyses on the character of services, Brekke and Test (10) found that Portals was high in service intensity and comprehensiveness. They also found that the majority of the services were delivered in vocational, independent-living, and social domains.

Recent analyses of functional outcomes over a three-year period found that Portals was superior to low-intensity case management in achieving change in hospitalization, vocational, social, and independent-living outcomes (21). Given these findings on the character and effectiveness of services at Portals, it provided a creditable service condition for testing the relationships between critical service ingredients and prospective functional outcomes.

Measures

The data for the study came from two sources. First, all study subjects participated in face-to-face semistructured interviews at baseline and at six and 12 months after baseline, and these data constituted the outcome measures. Second, staff recorded their daily service contacts with study subjects, and these data yielded the measures of intensity and continuity.

Functional outcomes.

Three functional outcome measures were used in this study: the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (28), the Role Functioning Scale (RFS) (29,30), and the Strauss and Carpenter Outcome Scale (SCOS) (31). The SCOS is a four-item scale that has been widely used in schizophrenia outcome research.

Green and Gracely (32) selected the RFS and GAS as outcome scales of choice for a population of patients with chronic mental illness. From the RFS we used three items that measured work, social, and independent-living outcomes. Possible total scores on the three items ranged from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating better functioning. The GAS is a measure of psychosocial adjustment that yields a single score ranging from 0 to 100. For this study the two variables measuring functional outcome were the total score from the three RFS items and the GAS rating.

All of the scale ratings were derived from a face-to-face interview instrument, the Community Adjustment Form (33). The ratings were derived according to procedures outlined by Brekke (34). Interrater reliability using the intraclass correlation was established during intensive rater training and during booster rating assessments throughout the study period. The intraclass correlation on the outcome items ranged from .75 to .98 (mean=.89).

Clinical outcomes.

Two measures of clinical outcome were used. The measure of symptomatology was the overall score from a 22-item version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (35). The interrater reliability (intraclass correlation) on the BPRS items ranged from .74 to .98 (mean=.92). The second measure was the hospitalization item from the SCOS, which measures the amount of hospitalization in the previous six months. Possible scores on the hospitalization item range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating less hospitalization.

In all analyses of functional or clinical outcomes, change scores were used. The change scores were calculated by subtracting baseline scores from six- and 12-month outcome scores. This approach allowed us to examine the relationships between service characteristics and the actual amount of rehabilitative change that occurred. The reliability of change scores has been criticized, but recent arguments for the validity of their use have been presented by Rogosa (36).

At each interview, we also gathered data from the subjects on medication type, dosage, and number of days on antipsychotic medication.

Service characteristics.

Measures of service characteristics were derived from the Daily Contact Log (DCL) (21,23,2410,37,38). Program staff filled out the DCL on a daily basis for each contact they had with individual clients. Although the DCL measures face-to-face, telephone, and indirect contact that staff have with clients, it does not capture time that clients spend in the program milieu when they are not directly engaged with staff. The reliability and validity of the DCL have been discussed by the first author (38), and the psychometric procedures outlined in that paper were followed in this study.

The DCL yields measures of several important service delivery characteristics; among them are the intensity of services and gaps in services. In this study, intensity was measured as the minutes of staff-client contact summed over six or 12 months. Longitudinal continuity was measured as the number of gaps in treatment. A gap in treatment was defined as a 30-day period during which no staff-client contact occurred. This definition was based on the consensus judgment of the clinicians at Portals. Intensity and longitudinal continuity scores were derived for each subject at six and 12 months.

Results

Before the study hypotheses were tested, several issues needed to be addressed. Of the 11 subjects who left treatment after six months, eight were men (73 percent), and seven were white (64 percent). Their mean±SD age was 33±7 years, and their mean±SD GAS score was 29±8. No statistically significant differences were noted between subjects who completed treatment and those who left. In addition, no statistically significant relationships (or trends) were found between the amount of functional change after six months of treatment and whether subjects left or remained in treatment.

During the first six months of treatment, subjects received a mean±SD of 93±74 contacts, with a mean±SD duration of 31±9 minutes per contact. The mean frequency of contacts for the entire 12-month period was 125±101 contacts, and the mean duration of all contacts was 30±9 minutes per contact. Subjects received nearly three times as much service over the first six months of the study as during the second six-month period, which is consistent with data presented by Brekke and Test (10).

The gaps in service also increased over time, from a mean±SD of .7±.8 gaps in the first six months to 2.3±1.6 gaps over 12 months. The correlation between service intensity and continuity was quite high at six months (r=-.59, p<.001) and at 12 months (r=-.74, p<.001).

We also examined the correlations between baseline levels of functioning (using the four outcome measures) and both the intensity and continuity of services at six months and 12 months. The one significant relationship was that higher ratings on the GAS at baseline, which reflect higher functional levels, were associated with receiving a lower intensity of services over 12 months (r=-.39, p<.05). The range in the correlation coefficient for the nonsignificant relationships was -.34 to .33. In general, these findings indicated that the intensity and continuity of services were not related to a subject's level of functioning at baseline.

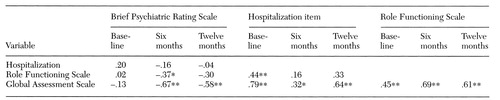

The correlations between the dependent variables are presented in Table 2. Based on our previous work (34), we expected the GAS to be significantly related to both clinical and functional outcomes, which was borne out in these analyses.

Another issue concerns medication use. In chlorpromazine equivalents, the mean±SD dosage at baseline was 514±494 mg, at six months it was 426±353 mg, and at 12 months it was 396±338 mg. None of the differences were statistically significant. Except for one subject taking clozapine, the subjects received typical antipsychotics.

The number of days on medication in the previous six months was determined. At baseline the mean±SD number of days was 160±41, at six months it was 170±35 days, and at 12 months it was 153±57 days. The only statistically significant difference was between the number of days at six and 12 months (t=-2.3, df=28, p<.03); however, the difference was not significant after a Bonferroni correction due to multiple comparisons.

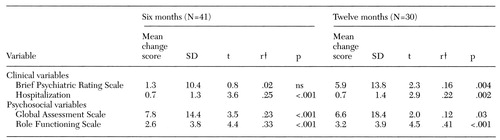

A previous comparative outcome study found Portals to be an effective rehabilitation environment in terms of change in work, independent-living and social outcomes, and hospitalization (21). This study used paired t tests to assess the degree of change on all outcome indicators for this sample (see Table 3). After six months of treatment, a statistically significant improvement was noted on all measures of functional outcome and one measure of clinical outcome—lower hospitalization rate. The change in symptom levels from baseline to six months was not statistically significant. The 12-month outcome data showed statistically significant improvement in the same functional and clinical domains; however, BPRS scores indicated that participants experienced a statistically significant increase in symptoms from baseline to 12 months.

The clinical significance of findings similar to these using this sample was established in a previous study (21). In the analyses reported here, nearly all of the average change scores at six and 12 months represent change that is near to or greater than one standard deviation of the range in raw scores at baseline. This was not the case with the BPRS scores; the average change score at six and 12 months ranged from .1 to .5 of a standard deviation of the score range at baseline. This finding suggests that the study hypotheses were tested on indexes of statistically and clinically significant rehabilitative change, except in the case of symptom levels.

Multiple hypothesis testingand type I error rate

The analyses in this study posed a dilemma. A number of hypotheses had to be tested with a relatively small sample size. In the social sciences we have traditionally stressed the control of type I error rate in this situation by the use of an alpha-limiting method such as the Bonferroni correction (39). However, alpha-limiting methods decrease power and emphasize p values rather than effect sizes (40). Because power is generally low in the social sciences and effect sizes are much more informative than p values, some researchers have been critical of using alpha-limiting methods (41,42). Our approach was to focus on effect sizes (r and R2) while cautioning that the reliability of the estimates may be questionable in some cases because of the small sample size.

For the reader who requires an alpha correction, we propose controlling the type I error rate for each group of analyses by using a familywise correction as advocated by Dar and associates (43). They propose defining families of variables based on conceptual criteria and then using a Bonferroni correction within the families. In this study we have two conceptual families of dependent variables, the clinical and the psychosocial. Although we still report significance levels at .05 and below, we also indicate which findings are statistically significant after the Bonferroni correction.

We also sometimes used omnibus multivariate procedures, which have been a traditional protection against inflation of the type I error rate. However, we must stress that some of the effect sizes we report may have clinical significance despite the lack of statistical significance after the alpha-correcting methods are used.

Concerning the strength of the findings presented here, Cohen (44) suggests that in social and psychological research, an R2 value of .01 is a small effect size, .09 is a medium effect size, and .25 is a large effect size. The corresponding values of r are .1 for a small effect size, .3 for a medium effect size, and .5 for a large effect size.

Study hypotheses

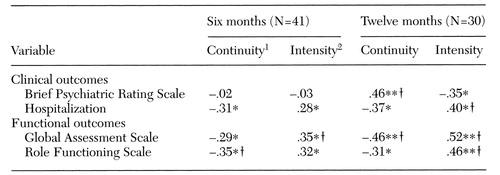

We tested the study hypotheses by first examining the bivariate correlations between the service characteristics (intensity and longitudinal continuity) and prospective change in outcomes at six and 12 months. As shown in Table 4, at six months significant relationships were found between greater intensity and continuity of services and improvement in the GAS score, the RFS score, and hospitalization rates. At 12 months significant relationships were found between greater intensity and continuity of services and improvements in the GAS score, the RFS score, and hospitalization rates.

In regard to symptom change as measured by the BPRS, significant relationships were found between greater intensity and continuity of services and lower symptom change scores (less symptom elevation) at 12 months. Although half of the bivariate relationships that were significant at .05 were not statistically significant after the Bonferroni correction, we would emphasize that the majority of the effect sizes are in the medium and large ranges.

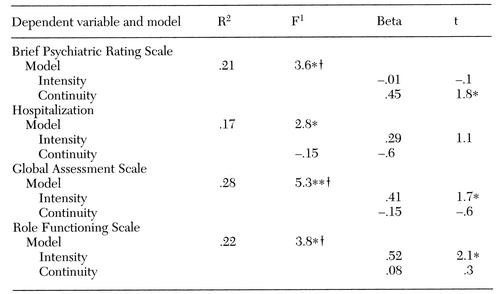

In a second set of analyses, we regressed the change scores at six and 12 months onto the service characteristics at each time. Given the small sample size and the multicollinearity among the predictors, some of the results of the regression analyses should be interpreted with caution, especially with regard to the statistical significance of the individual betas. Table 5 presents the regression results from the 12-month analyses.

Given the directionality of the hypothesized effects, one-tailed tests of statistical significance were used. To provide some protection against inflation of the type I error rate in the multiple regression analyses, we did omnibus canonical correlation analyses that examined the multivariate relationships at 12 months between the service characteristics and the two clinical outcome variables, and then between the service characteristics and the two functional outcome variables. In both cases the omnibus F was statistically significant (for the service characteristics and the two clinical variables, Wilk's lambda=.66; F=2.96, df=4,52, p<.02; for the service characteristics and the two functional variables, Wilk's lambda=.68; F=2.8, df=4,52, p<.02).

Turning to the multiple regression results, from Table 5 it can be seen that all of the equations using the 12-month data were significant at .05, and three of the four were statistically significant after the Bonferroni correction. The R2 values indicated that 28 percent of the variance in GAS change scores, 22 percent of the variance in RFS change scores, 17 percent of the variance in hospitalization change scores, and 21 percent of the variance in BPRS change scores were accounted for by the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services.

With regard to symptom change scores, the sign of the beta indicated that greater continuity and intensity of services were related to less symptom change and, hence, less elevation in symptom scores. It should also be noted from the t values of the individual betas that service continuity had more relative influence on symptoms than service intensity. Conversely, intensity had more relative influence than continuity on the three functional outcomes.

The results at six months indicated that the multiple regression equations for change in hospitalization, RFS, and GAS scores were significant at .05, with the R2 values ranging from .11 to .14. None of the equations was statistically significant after the Bonferroni correction, and the Wilk's lambda of .76 (F=1.8, df=4,72) was significant at .06. However, these effect sizes were in the medium range, and after six months of psychosocial rehabilitation, between 11 and 14 percent of the variance in GAS, RFS, and hospitalization change scores was accounted for by the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services. On the other hand, the combination of service intensity and longitudinal continuity did not account for a significant amount of variance in symptom change scores at six months.

In summary, these bivariate and multivariate results generally supported the hypotheses that greater intensity and longitudinal continuity of services are related to improvement on indicators of hospitalization and psychosocial functioning after both six and 12 months of psychosocial rehabilitation. Given that symptoms increased from baseline to 12 months, these results indicated that greater intensity and longitudinal continuity of services were related to less of an increase in symptoms. It should also be noted that the effect sizes in these analyses were generally in the medium and large ranges, which is notable given the lack of previous findings in this area.

A final issue concerns the increase in symptoms from baseline to 12 months during the intervention. The data reported above on medication use could provide a possible explanation. However, those data suggested that although medication dosage and days on medication tended to decline over time, the changes were not statistically significant. In another analysis of these data, the correlations between symptom change scores and both change in dosage and change in medication days at six and 12 months were not statistically significant (p>.4 in all cases). This finding suggests that medication use as it was measured in this study does not adequately explain the increase in symptom levels over time.

Discussion

This study was the first to examine the relationships between the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services received by individual clients and their prospective functional outcomes during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation. The setting for the study was the first 12 months of treatment in a rehabilitation program that had been shown to be effective in a previous study. The hypotheses that greater intensity and continuity of services would be associated with higher levels of rehabilitative improvement on measures of clinical and functional outcomes after six and 12 months of rehabilitation were supported. These findings mean that clients who received more contact hours with staff and had fewer gaps in service delivery achieved greater rehabilitative change in social, work, and independent-living domains, as well as in the rate of hospitalization.

The magnitude of the impact of the service characteristics was also notable. On average, more than 20 percent, and as much as 28 percent, of the change in outcomes after 12 months of rehabilitation was explained by the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services. Concurrent with these rehabilitative improvements, a significant increase in symptom levels was also noted after 12 months. However, greater continuity and intensity of services was associated with less increase in symptoms over time.

These findings have several implications. First, it appears that service intensity and longitudinal continuity during rehabilitation are potentially critical service constructs around which to organize service delivery. Previous studies on the impact of service ingredients that used the program as the unit of analysis are particularly relevant for issues of program planning, development, and design; however, as noted previously (21), their findings are not generalizable to individual clients.

This study used the client as the unit of analysis. Therefore, we can conclude that the service ingredients of intensity and longitudinal continuity can be used to guide practice for individual clients during psychosocial rehabilitation. Specifically, if the goal is improved functional outcomes, reduced hospitalization, and better symptom outcomes for individual clients, then the services they receive should be intensive and provided with longitudinal continuity during the first 12 months of the intervention. Evidence was also found to suggest that the continuity of the intervention was related more strongly to symptom outcomes and that intensity was more strongly related to functional outcomes. This finding suggests that symptom change is more dependent on consistency of service than on service intensity, while functional change is more dependent on service intensity.

Another important implication concerns how much intensity and continuity of services are needed to achieve significant rehabilitative improvement. During the first six months of services, clients in this study received an average of four staff contacts a week, lasting about 30 minutes each. Also, clients generally had less than one 30-day gap in contact during this time. During the second six months, clients averaged 1.5 staff contacts a week, lasting about 30 minutes each, with less than two gaps during the six-month period. It can be concluded that these average levels of service intensity and continuity were associated with significant rehabilitative improvement, and, further, that within these service parameters, clients who received more services and had fewer gaps achieved significantly better clinical and functional outcomes. We do not know, however, whether these levels of intensity and continuity represent minimum or maximum amounts that are necessary for rehabilitative change to occur.

A third implication concerns the impact of changes in service delivery characteristics over time. In this study most of the rehabilitative improvement that we found over 12 months in treatment occurred during the first six months, when the services were most intense and continuous. Nonetheless, these rehabilitative gains were maintained during the second six months of rehabilitation even though service intensity decreased by more than 200 percent and the number of service gaps doubled. This finding suggests that treatment intensity and continuity can be faded over time without losing the rehabilitative gains made during the early phase of the intervention.

On the other hand, it is not known whether maintaining the initial levels of service intensity and continuity during the second six months of rehabilitation would have yielded greater functional improvement during that period. Snowden and Clancy (22) found evidence of diminishing returns when high levels of service intensity were maintained over time, although the service setting they investigated was quite different than the one in this study. The hypotheses about how much intensity or continuity is needed to create and maintain change, or whether different levels of these service ingredients are needed at different phases of treatment, should be investigated.

Concurrent with significant rehabilitative improvements, a statistically significant increase was noted in symptom levels from baseline to 12 months. The change from baseline to six months was not significant. Variations in self-reported medication use were not related to the symptom increase; however, this finding does not rule out a medication effect because the accuracy of self-reported data on medication use could be questioned. Another possible explanation for the increase in symptoms is that the demands of participating in a change-oriented psychosocial treatment led to an increase in stress, which in turn led to an increase in symptoms. Support for this explanation comes from studies on psychosocial rehabilitation that found increases in relapse related to increased demands for functional improvement (7,45).

Studies of the relationship between neurobiological variables and psychosocial functioning have also found that certain cognitive and psychophysiological deficits co-occur with increases in both functional status and symptoms (46,47). However, it is important to remember that in this study the elevations in symptoms did not preclude functional improvement, nor did they result in more frequent hospitalization. This finding suggests that clinicians might want to inform clients and family members that some increase in symptoms might accompany intensive rehabilitation. It also argues for instituting symptom, stress, and medication management strategies when rehabilitation begins. It is also clear that further understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms involved in this interplay between functional improvement and symptom exacerbation is necessary. Finally, it should be noted that we did not find evidence to support the clinical significance of the symptom elevations that occurred in this study.

Another aspect of these findings deserves comment. Little relationship was found between the level of client functioning at baseline and the subsequent intensity or continuity of services delivered to clients. This finding suggests that effective services can be delivered without adjusting the intensity or longitudinal continuity of the services to the clients' initial level of psychosocial performance. It is possible that making such adjustments could further increase rehabilitative change, but future studies will have to address that issue. This finding also suggests that program staff were not selecting (or creaming) the highest-functioning clients to receive the most intensive contact with staff.

Several limitations and caveats must be considered with regard to these findings. First, even though this study used a prospective design, the sample was relatively small. While we tried to balance the concern over inflation of the type I error rate with a focus on effect sizes, these results must be replicated on larger samples. However, it should be noted that several replications on smaller samples would increase confidence in these results, and those results would also be generalizable to programs with fewer consumers. Second, it is also unclear whether the relationships between intensity and continuity of services and functional improvement found during the first year of psychosocial rehabilitation would be found in subsequent years. It is possible that the strength of the relationships could increase or decrease over time, or that there might be other service characteristics, such as individualization of treatment, that could become more salient after the first year of the intervention.

Third, there are many different models of community-based care. The degree to which the findings from this study would generalize to other models, such as assertive community treatment or intensive case management, is unknown. Fourth, the measure of service characteristics used here captures staff-client contact time but not the total time that clients spend in the program milieu. Therefore, we do not know whether these relationships would exist if total program time were used as the measure of service characteristics.

Fifth, we studied only two process variables out of a potentially large number previously described by Brekke and Test (10). Future studies must examine the impact of other important service characteristics on functional outcomes and examine the relationships among the process variables themselves. For example, it is possible that the quality of the client-staff working alliance has an impact on the intensity and continuity of services that clients receive.

Finally, although the intensity of services and longitudinal continuity of care are conceptually distinct, they were highly correlated in this study. It is possible for continuity of care and service intensity to be more independent than they were in this intervention, in which clients are seen on the average of about four times a week in the first six months and more than once a week after that. For example, a client seen once a week over the 12-month period would have no gaps in treatment but would have a relatively low intensity score. Conversely, a client could be seen for five days a week during certain periods but then retreat from treatment for weeks at a time and thus have treatment gaps. On this basis, the nature of the intervention might influence the correlation between these variables as much as the nature of the variables themselves.

Nevertheless, because both these service processes reflect a quantitative service domain, it is likely that they will sometimes be correlated at high levels. This correlation makes assessing the statistical significance of their unique contribution to service outcomes harder to establish in a multivariate statistical model. For example, in the regression analyses reported here, evidence was found that service intensity accounted for more unique variance in functional outcomes than continuity did, and, conversely, that continuity was more strongly related to symptom outcomes than was intensity. However, due to the impact of the collinearity among the service characteristics, these findings must be replicated on larger samples. It is also possible that the unique contributions of intensity and longitudinal continuity will be easier to assess in studies with longer follow-along periods or in differing models of care. Clearly, the relationship between these two variables needs to be examined in a variety of service contexts.

Based on the findings of this study, clinicians, administrators, and researchers can assume that the intensity and longitudinal continuity of services are important to achieving rehabilitative outcomes in some community-based psychosocial rehabilitation models. Further study is needed to refine how much of each service ingredient is needed, how its relative importance might vary with the phase of treatment or with the type of outcome measured, and how these variables interact with other intervention processes. It is also clear that the search for critical service ingredients in psychosocial rehabilitation must attend to programmatic and clinical concerns by using both the program and the client as the units of analysis in future studies.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant MH-43640 awarded to Dr. Brekke by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Brekke is associate professor and Ms. Slade is a doctoral candidate at the School of Social Work of the University of Southern California, MC-0411, Los Angeles, California 90089-0411 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Ansel is in private practice in Kamuela, Hawaii. Dr. Long is assistant professor in the department of psychology at St. John's University in New York City. Mr. Weinstein is chief executive officer of Portals Mental Health Rehabilitation Agency in Los Angeles.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and measures of baseline functioning of patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program at six and 12 months

1Possible scores range from 22 to 54, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms

2Measured using the hospitalization item from the Strauss and Carpenter Outcome Scale. Possible scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating less hospitalization.

3Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

4Measured using three items from the scale. Possible total scores on the three items range from 3 to 21, which higher scores indicating better functioning

|

Table 2. Pearson correlations between outcomes variables at baseline, six, and 12 months measured among patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program

*p<.05

**p<.01

|

Table 3. Change scores on outcome variables at six and 12 months among patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program1

1Comparisons were made using paired t tests.

†r=t2(t2 + df)

|

Table 4. Correlations between service characteristics and six- and 12-month change scores among patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program

1Measured as the number of 30-day gaps in service

2Measured as the number of minutes of contact with direct-service staff

*p<.05(one tailed)

**p<.01(one tailed)

†Significant at the Bonferroni-corrected value of p<.0125

|

Table 5. Regression of 12-month change scores onto service characteristics at 12 months among patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program

1df=2,27

*p<.05

**p<.01

†Significant at the Bonferroni-corrected value of p<.025

1. Stroul B: Community support systems for persons with long-term mental illness: a conceptual framework. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 12:9-26, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Bond GR, McGrew JH, Fekete D: Assertive outreach for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:4-16, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Olfson M: Assertive community treatment: an evaluation of the experimental evidence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:634-641, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Scott JE, Dixon LB: Assertive community treatment and case management for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:657-668, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Solomon P: The efficacy of case management services for severely mentally disabled clients. Community Mental Health Journal 28:163-180, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Test MA: Community support programs, in Schizophrenia: Treatment, Management, Rehabilitation. Edited by Bellack AS. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1984Google Scholar

8. Test MA: Training in community living, in Rehabilitation of the Seriously Mentally Ill. Edited by Liberman RP. New York, Plenum, 1992Google Scholar

9. Brekke JS: What do we really know about community support programs? Strategies for better monitoring. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:946-952, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Brekke JS, Test MA: A model for measuring the implementation of community support programs. Community Mental Health Journal 28:227-247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Taube CA, Morlock L, Burns BJ, et al: New directions in research on assertive community treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:642-647, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Bachrach LL: Continuity of care and approaches to case management for long-term mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:465-468, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Bachrach LL: The biopsychosocial legacy of deinstitutionalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:523-524, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Talbott JA: The chronically mentally ill: what do we now know, and why aren't we implementing what we know? New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 37:43-58, 1988Google Scholar

15. Tessler RC: Continuity of care and client outcome. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:39-53, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Tessler RC, Mason JH: Continuity of care in the delivery of mental health services. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:1297-1301, 1979Link, Google Scholar

17. Test MA: Continuity of care in community treatment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 2:15-23, 1979Google Scholar

18. Tessler RC, Willis G, Gubman GD: Defining and measuring continuity of care. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 10:27-38, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Test MA, Scott R: Theoretical and research bases of community care programs, in Mental Health Care Delivery: Innovations, Impediments, and Implementation. Edited by Marks I, Scott R. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1990Google Scholar

20. Dietzen LL, Bond GR: Relationship between case manager contact and outcome for frequently hospitalized psychiatric clients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:839-843, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Brekke JS, Long J, Sobel E, et al: The impact of service characteristics on functional outcomes from community support programs for persons with schizophrenia: a growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:464-475, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Snowden LR, Clancy T: Service intensity and client improvement at a predominantly black community mental health center. Evaluation and Program Planning 13:205-210, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Audini B, Marks IM, Lawrence RE, et al: Home-based versus outpatient/inpatient care for people with serious mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:204-210, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sands RG, Cnaan RA: Two modes of case management: assessing their impact. Community Mental Health Journal 30:441-457, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed. New York, Biometrics Research, 1977Google Scholar

28. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 137:48-51, 1979Google Scholar

29. McPheeters HL: Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two Southern states. Community Mental Health Journal 20:44-55, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, et al: Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal 29:119-131, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I. characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:739-746, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Green RS, Gracely EJ: Selecting a scale for evaluating services to the chronically mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 23:91-102, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Test MA, Knoedler WH, Allness DJ, et al: Long-term community care through an assertive continuous treatment team, in Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology, Vol I: Schizophrenia Research. Edited by Tamminga C, Schultz S. New York, Raven Press, 1991Google Scholar

34. Brekke JS: An examination of the relationships among three outcome scales in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:162-167, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:578-602, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Rogosa D: Myths about longitudinal research, in Methodological Issues in Aging Research. Edited by Meredith W, Rawlings SC. New York, Springer, 1988Google Scholar

37. Brekke JS, Test MA: An empirical analysis of services delivered in a model community support program. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 10:51-61, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Brekke JS: The model-guided method of monitoring program implementation. Evaluation Review 11:281-299, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Toothaker L: Multiple Comparison Procedures. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

40. Cohen J: The earth is round (p<.05). American Psychologist 49:997-1003, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Schmidt F, Hunter J: Eight common but false objections to the discontinuation of significant testing in the analysis of research data, in What If There Were No Significance Tests? Edited by Harlow L, Mulaik S, Steiger J. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 1997Google Scholar

42. Sedlmeier P, Gigerenzer G: Do studies of statistical power have an effect on the power of studies? Psychological Bulletin 105:309-316, 1989Google Scholar

43. Dar R, Serlin RC, Omer H: Misuse of statistical tests in three decades of psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:75-82, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

45. Lamb RH, Goertzel V: High expectations of long-term ex-state hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 129:471-475, 1972Link, Google Scholar

46. Brekke JS, Raine A, Ansel M, et al: Neuropsychological and psychophysiological correlates of psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:19-28, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Tarrier N, Turpin G: Psychosocial factors, arousal, and schizophrenia relapse: the psychophysiological data. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:3-11, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar