Assessment of Suicide Risk 24 Hours After Psychiatric Hospital Admission

Abstract

Of 69 patients admitted to a hospital because of suicide risk, 30 (44 percent) were completely free of suicidal ideation 24 hours after admission. Scores on the Scale for Suicide Ideation at the time of admission distinguished patients who continued to have suicidal ideation 24 hours later (the sustained-ideation group) from those who did not (the transient-ideation group). Patients in the transient group were more likely than those in the sustained group to have made a suicide attempt during the week before admission. At admission patients in the sustained group were more likely to have psychotic symptoms and to report a family history of psychiatric illness.

Clinical judgment informed by an assessment of risk factors is the mainstay of decision making when clinicians are faced with the prospect of hospitalizing a potentially suicidal patient. Risk factors associated with suicidal behavior tend to have a high degree of sensitivity—that is, they are able to identify individuals who later commit suicide (1). However, they have low specificity, or little ability to exclude individuals who do not later commit suicide (1). Thus their predictive power is seriously compromised. Given the uncertainty of predicting suicidal behavior, clinicians tend to favor hospitalizing the patient, despite the lack of empirical data suggesting that acute hospitalization is effective in reducing suicide risk (2).

It has been our clinical impression that a substantial portion of patients admitted to our hospital because they are deemed to be at significant risk for suicide are no longer judged to be acutely suicidal the next day. The purpose of this study was to systematically investigate this clinical impression. If it was confirmed, we sought to determine whether selected demographic and clinical variables could distinguish the transiently suicidal group (called the transient group) from the remaining patients who continued to be acutely suicidal 24 hours after admission (called the sustained group).

Methods

Subjects consisted of 26 men and 43 women patients admitted to the Hillside Hospital-Long Island Jewish Medical Center with suicide risk sufficient to warrant hospitalization, as judged by the admitting physician. All but four patients were admitted on a voluntary basis. Patients were excluded if they lacked capacity to give written informed consent for participation. No patients were excluded based on diagnosis.

All 69 patients were assessed approximately 24 hours after admission to the inpatient service. Nineteen of these patients were also interviewed at the time of admission because research staff were available. The interview protocol was the same for the subsample of 19 patients assessed at the time of admission; the study instruments were administered twice to these patients.

Data gathered during the interview included demographic information and history related to psychiatric illness and treatment. Several instruments were administered, including the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI) (3), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (4), the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (5), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (6), and the Life Events Inventory (7). Additional data collected consisted of DSM-IV axis I and axis II diagnoses obtained from the admission medical record; serum cholesterol, because of the observed association between low serum cholesterol and suicidal behavior (8); and length of stay on the inpatient service.

Patients were classified as being transiently suicidal if at the 24-hour follow-up a score of zero was obtained for the first five items on the SSI, indicating a total absence of suicidal ideation. Patients who reported any suicidal ideation at the 24-hour follow-up as measured by the SSI were classified as being in the sustained group.

Comparisons between the transient group and the sustained group were conducted using chi square analyses for noncontinuous variables and independent t tests and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Results

Of the 69 patients admitted because of suicide risk, 30 (44 percent) were found to be completely free of suicidal ideation 24 hours after admission. The mean±SD age of the patients in this group was 38±18 years. The other 39 patients were classified as being in the sustained group at 24 hours. Their mean±SD age was 38±12 years.

No significant differences between the transient and sustained groups were found in gender, race, religion, marital status, children under 18 years old at home, living alone, employment status, managed care status, level of education, age, and number of life stressors and their perceived severity. The transient and sustained groups did not differ in the proportion of patients with axis I affective disorders (83 percent and 87 percent, respectively), axis II disorders (30 percent and 36 percent), substance abuse history (10 percent and 28 percent), and family history of suicide (37 percent and 36 percent).

In addition, no differences were found between the transient and sustained groups in the mean±SD number of lifetime suicide attempts (1.7± 1.9 and 3.1±5.1 attempts, respectively), number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations (3±5.8 and 5.1±7.4), serum cholesterol (195±40 and 201± 51 mg/dL), and length of stay (16± 14.2 and 15.5±11.5 days).

Patients in the transient group were significantly more likely than those in the sustained group to have made a suicide attempt in the week before admission (50 percent versus 23 percent; χ2=5.42, df=1, p=.02). Patients in the sustained group were significantly more likely to have a family history of psychiatric illness than patients in the sustained group (47 percent versus 68 percent; χ2=6.26, df=2, p=.04) and to have psychotic symptoms on admission (43 percent versus 66 percent; χ2=3.76, df=1, p=.05).

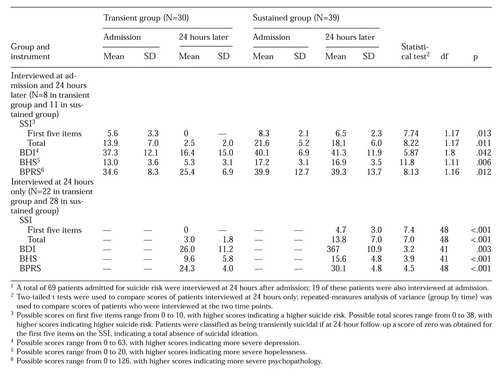

Psychological measures were analyzed separately for patients evaluated 24 hours after admission only and for those evaluated both at admission and 24 hours later. Not surprisingly, as shown in Table 1, patients in the transient group had lower scores on all scales, indicating significantly less severe symptoms and less impairment at admission and at 24-hour follow-up than patients in the sustained group. As Table 1 shows, a significant group-by-time interaction was evident in scores on the SSI, BDI, BHS, and BPRS for the 19 patients assessed on two occasions; all scores improved 24 hours after admission for the patients in the transient group.

Moreover, patients' scores at admission on the total SSI and on its first five items predicted whether they would be classified at 24 hours as being transiently suicidal or in the sustained group. At admission, the SSI scores of patients in the transient group were significantly lower than those of patients in the sustained group, both the total SSI score (t=2.62, df=12.4, p= .022) and the score on the first five SSI items (t=2.14, df=17, p=.047).

Discussion and conclusions

Using the criterion for "suicide non-ideators" proposed by Beck and associates (3), we confirmed our clinical impression that many patients admitted because of suicide risk no longer presented an imminent suicide risk 24 hours after admission. Many possible explanations can be offered for this observation, ranging from the possibility that patients initially presented an exaggerated suicide risk and were inappropriately admitted to the view that patients genuinely benefited from the safety, respite, and support of hospitalization.

These preliminary findings suggest directions for future investigation. SSI scores at the time of admission were associated with membership in the transient and sustained groups 24 hours after admission—lower scores were associated with transient suicidal ideation, while higher scores were associated with sustained ideation. We unexpectedly found that patients who recently made a suicide attempt were less likely to have suicidal ideation 24 hours after admission. A suicide attempt may discharge dysphoric affect and ameliorate suicidal ideation. A similar idea has been proposed with respect to self-injurious behavior of patients with borderline personality disorder (9).

We are not suggesting any changes in the current clinical practice of careful individualized assessment of suicide risk and need for hospitalization. This exploratory study is limited by its small sample size, large number of variables, absence of structured diagnostic assessment, and high percentage of voluntary patients. In addition, the study did not examine the decision-making characteristics of physicians. These limitations affect the validity and generalizability of our findings.

Nonetheless, these preliminary results are encouraging in that they point to the utility of a post hoc approach to refining tools for assessing suicide risk without risking lives. For example, further testing of the SSI as an indicator of suicide risk may lead to the identification at the time of hospital admission of patients who are likely to exhibit significant improvement in the short run. These patients may benefit from rapid reassessment and referral to treatment in the community.

Dr. Russ is director of acute care psychiatry and Dr. Bajmakovic-Kacila is staff psychiatrist at Hillside Hospital-North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System, Glen Oaks, New York 11004 (e-mail, [email protected]), where Mr. Kashdan was a research assistant when this work was done. Mr. Kashdan is now a graduate student in the department of psychology at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Dr. Pollack is professor of statistics in the computer information systems and decision sciences department at St. John's University in Jamaica, New York.

|

Table 1. Scores on the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) of patients interviewed at hospital admission and 24 hours later, by whether they were free of suicidal ideation 24 hours (transient group) or not free (sustained group) 1

1. Mann JJ: Psychobiologic predictors of suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 48(suppl 12):39-43, 1987Google Scholar

2. Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

3. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consultation and Clinical Psychology 47:343-352, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for Revised Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1987Google Scholar

5. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for Beck Hopelessness Scale. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1988Google Scholar

6. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Cochrane R, Robertson A: The Life Events Inventory: a measure of the relative severity of psychosocial stressors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 17:135-139, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Golier JA, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, et al: Low serum cholesterol level and attempted suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:419-423, 1995Link, Google Scholar

9. Kemperman I, Russ MJ, Shearin E: Self-injurious behavior and mood regulation in borderline patients. Journal of Personality Disorders 11:146-157, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar