Reliability and Acceptability of Psychiatric Diagnosis Via Telecommunication and Audiovisual Technology

Abstract

The reliability of psychiatric diagnoses made remotely by telecommunication was examined. Two trained interviewers each interviewed the same 30 psychiatric inpatients using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Fifteen subjects had two in-person interviews, and 15 subjects had one in-person and one remote interview via telecommunication. Interrater reliability was calculated for the four most common diagnoses: major depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and alcohol dependence. For each diagnosis, interrater reliability (kappa statistic) was identical or almost identical for the patients who had two in-person interviews and those who had an in-person and a remote interview, suggesting that reliable psychiatric diagnoses can be made via telecommunication.

Telemedicine is one means of providing expert medical treatment to patients distant from a source of care (1). It has been suggested for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in remote locations or where medical expertise is scarce. Although pilot studies in telepsychiatry have been conducted since the 1950s, the high cost of providing the needed technology has impeded its widespread use (1,2). In recent years, however, new technological advances and increasing affordability are making telepsychiatry more feasible to address the maldistribution of psychiatric expertise.

To use this new technology in psychiatry, it must be demonstrated that psychiatric diagnosis and treatment conducted remotely via telecommunication is as reliable and effective as diagnosis and treatment conducted in person. Pilot studies have demonstrated high interrater reliability in the diagnosis of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (3) and schizophrenia (4).

In this study we compared interrater reliability of and patient satisfaction with in-person and remote diagnosis in a mixed-diagnosis group of psychiatric inpatients.

Methods

Two trained raters each interviewed the same 30 psychiatric inpatients using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-III-R) (5). The interviews took place one or two days apart between July 1996 and January 1997. Fifteen subjects were randomly assigned to two in-person interviews, one by each clinician, and 15 subjects were assigned to one in-person and one remote interview, one by each clinician. The two interviewers alternated performing the first interview. For patients who had both an in-person and a remote interview, the interviewers alternated performing the remote interview.

The in-person interview took place in an office at the Baltimore Veterans Affairs mental hygiene clinic. For the remote interview, the patient and interviewer were each in different offices of the clinic. They were connected by audiovisual communication, which allowed the patient and interviewer to hear and see each other throughout the interview.

Two video-conferencing units (Omega Flex Plus from VSI Enterprises, Inc.) were used. The video input system included an analog video camera with scanning and zoom functions. The camera in the office with the patient contained three chips for greater video acuity, while the camera in the clinician's office had only one chip. The higher-quality camera was used in the patient's room, as we felt that it was more important for the interviewer to observe the patient's nonverbal behaviors than for the patient to observe the interviewer. Video output utilized a 27-inch color monitor. The audio input-output system included high-quality desktop microphones and integrated speaker monitors. The system was set up to use a half T1 transmission speed (768 kilobits per second).

Interrater reliability was calculated for the four most common current diagnoses among the 30 patients: major depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and alcohol dependence. Some patients had multiple diagnoses. The kappa statistic (6) was used to assess the extent of agreement between the two raters.

A patient satisfaction scale (available on request from the first author) was developed to evaluate patient satisfaction with the in-person versus the remote interview. The scale consisted of 15 statements such as "I was satisfied with this examination," "I could hear the interviewer well," "The interview seemed very mechanical," and "I had a difficult time understanding what the interviewer was asking." Response categories were strongly agree, 1; agree, 2; disagree, 3; and strongly disagree, 4. Scoring was reversed for questions that indicated dissatisfaction with the interview. The satisfaction scale was administered twice to each subject, once after each of the two interviews.

Results

No significant differences in age or educational level were found between patients who had two in-person interviews and those who had an in-person and a remote interview. However, a significant difference in race was found between groups (χ2=8.8, df=2, p<.01). A significantly higher percentage of subjects in the in-person-remote condition were African Americans (73 percent) compared with the in-person-in-person condition (20 percent). No differences between groups were found in the percentage of patients who were diagnosed by at least one of the two raters as having major depression, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse, or panic disorder.

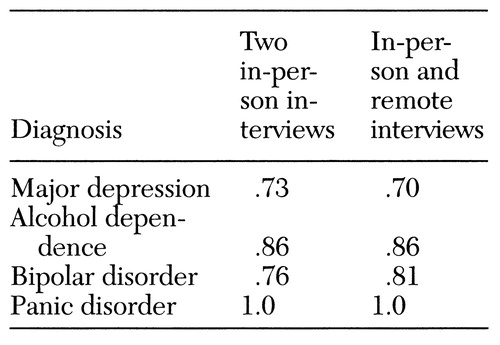

Table 1 shows that for each of the four most common diagnoses, the kappa statistics were identical or nearly identical for the group that had two in-person interviews and the group that had an in-person and a remote interview, indicating comparable reliability. In both interview conditions, kappas were high and comparable to those in other studies using the SCID as a diagnostic instrument (7).

The 15 patients who had an in-person and a remote interview were asked to rate their satisfaction with the two interviews. No significant difference in satisfaction scores was found (mean scores of 24.7 for the in-person interview and 24.9 for the remote interview). Almost all patients responded "agree" or "strongly agree" to all items for both interviews. Thus satisfaction was virtually identical for the two interviews.

The 15 subjects who had both an in-person and a remote interview were asked three additional questions. In response to the question "Overall, which did you prefer?" ten subjects preferred the in-person interview, no subjects preferred the remote interview, and five subjects responded that both were about the same. In response to the question "Would you rather have a video examination with a psychiatrist or an in-person examination by a general practitioner who might know a little less about psychiatry?" 12 subjects preferred the video examination, and three subjects preferred the in-person examination.

Finally, in response to the question "If you lived two hours away from the hospital, would you rather travel to the hospital to see the psychiatrist in person or go to a place close to your home and see the psychiatrist by video?" three subjects chose to travel to see the psychiatrist, and 12 subjects chose to see the psychiatrist by video.

Discussion and conclusions

Psychiatric diagnosis for the four most common disorders in the study sample was as reliable when interviews were conducted remotely as when they were conducted in person. Other studies have also found that psychiatric diagnoses can be made reliably through remote telecommunication (3,4).

Our study design had two unique features. First, two interviews were conducted independently by different raters rather than having a single interview conducted by one rater and observed by a second rater, as in most other studies. High interrater reliability was achieved despite this more rigorous design. Second, patients with a variety of diagnoses were evaluated using the SCID. Other studies used clinician rating scales of symptoms with a group of patients who had one diagnosis in common (3,4).

The results of the satisfaction scale indicated that patients were generally accepting of telepsychiatry for diagnostic purposes. In fact, satisfaction scores for the remote and in-person interviews were not significantly different. When subjects were offered a preference, they usually chose an in-person interview, but most subjects stated they would prefer a remote interview with a psychiatrist to an in-person interview with a less-trained clinician. Furthermore, most subjects stated they would prefer a remote interview close to their homes to an in-person interview at a distance from their homes.

In summary, the results of this preliminary study indicate that when audiovisual technology was used, four common psychiatric diagnoses were arrived at with the same reliability as in an in-person interview and with high levels of patient satisfaction. These findings support the potential utility of telepsychiatry at least for diagnostic purposes in areas underserved by psychiatrists. Further studies are in progress to determine whether the effectiveness of treatment by telecommunication for such diagnoses compares favorably to that of treatment at the point of service.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Telecommunication equipment was provided by VSI Enterprises, Inc.

Except for Dr. Rosen, the authors are affiliated with the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Rosen is with the University of Maryland Medical School in Baltimore, as is Dr. Ruskin, Dr. Kling, Dr. Siegel, and Dr. Hauser. Send correspondence to Dr. Ruskin at the Baltimore VA Medical Center, Psychiatry Service (116A), 10 North Greene Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Interrater reliability (kappa) of the four most common diagnoses based on two in-person interviews (15 patients) or one in-person and one remote interview using telecommunications (15 patients)

1. Bradham DD, Morgan S, Dailey ME: The information superhighway and telemedicine: applications, status, and issues. Wake Forest Law Review 30:145-166, 1995Google Scholar

2. Benschoter RA, Wittson CL, Ingham CG: Teaching and consultation by television. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 16:25-26, 1965Google Scholar

3. Baer L, Cukor P, Jenike MA, et al: Pilot studies of telemedicine for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1383-1385, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Zarate CA Jr, Weinstock L, Cukor P, et al: Applicability of telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: acceptance and reliability. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:22-25, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Edition (With Psychotic Screen). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

6. Fleiss JL: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 1981Google Scholar

7. Segal DL, Hersen M, Van Hasselt VB: Reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R: an evaluative review. Comprehensive Psychiatry 35:316-327, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar