A Comparison of Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Substance Users in the Psychiatric Emergency Room

Abstract

Current illicit drug and alcohol users were identified by laboratory evaluation of urine samples from nonpsychotic patients without a primary clinical diagnosis of a substance use disorder seen in a psychiatric emergency room. Urine screens revealed that 32 of 93 nonpsychotic patients (34 percent) had used a substance just before visiting the emergency room. Compared with nonusers, users were more often Caucasian females with adjustment disorders who admitted their previous substance use. The prevalence of concurrent use among nonpsychotic patients was higher than among psychotic patients. Nonpsychotic and psychotic users differed in gender, marital status, level of suicidality, self-report of use, the clinician's suspicion of use, use of seclusion during the visit, admitting status, level of care, and disposition.

Although high rates of active substance abuse occur among patients seen in psychiatric emergency rooms, clinicians are largely unable to discern which emergency room patients are likely to be using illicit drugs at the time they appear for treatment (1,2). Numerous studies have documented the impact of comorbid substance use on both the course and the treatment of psychiatric illness (3), highlighting the need for reliable detection of this condition.

Concurrent substance abuse most likely presents at different rates and in different ways in different patient groups (4), suggesting that patient populations in various treatment settings should be evaluated in naturally occurring subgroups to gauge the incidence of these disorders and their typical presentation. In this study, laboratory evaluation of urine was used to determine the presence of alcohol and illicit substances and to establish rates of concurrent substance use in a sample of nonpsychotic patients seen in a psychiatric emergency room who did not have a primary clinical substance-related diagnosis. Profiles of substance-using patients (both drug and alcohol users) were then characterized with logistic regression modeling. Finally, results were contrasted with findings on the incidence and nature of concurrent substance use in a psychotic patient group presenting for treatment during the same time period in the same setting (2).

Methods

The study took place in the psychiatric emergency room of Parkland Hospital in Dallas, a county-owned, inner-city teaching hospital. At the time of this study (June and July 1993) approximately 720 patients a month presented for treatment, of whom 17 to 19 percent were hospitalized. Maximum length of stay in the emergency room was up to 24 hours.

Study methods have been described elsewhere (2). Briefly, a urine drug screen was used for a sample of 440 consenting adult patients presenting for treatment. Ninety-three of those providing urine received a nonpsychotic, non-substance-related clinical diagnosis and had medical records available for review after the visit. Records contained demographic information such as age, gender, and ethnicity as well as information about the visit such as admitting status, DSM-III-R diagnosis, level of care provided, and disposition. Nonpsychotic diagnoses were grouped for purposes of analyses into the categories of adjustment disorder, personality disorder, nonpsychotic mood disorders, and other.

Patients were identified as concurrent substance users if laboratory testing confirmed the presence of at least one substance that could not be correlated with a physician-prescribed medication. Conventional immunoassays followed by appropriate chromatographic confirmations were used to establish drug use, as previously reported in a psychotic population (2).

Demographic and clinical variables were compared using chi square tests. Important predictors of substance use status were identified in a logistic regression analysis from among several variables. They included age (18 to 45 years and 46 years and older), gender, admitting status (voluntary and involuntary), housing status (homeless and not homeless or status unknown), accompanied to the emergency room by a family member or friend (yes and no or unknown), marital status (married and not married or unknown), level of suicidality (no ideation or behavior, ideation only, and behavior), employment status (employed and not employed or unknown), history of substance use (yes and no or unknown), time of admission (7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and 7 p.m. to 7 a.m.), day of admission (weekend and weekday), diagnosis, level of care, disposition (hospital and other), and whether drug use was suspected by the clinician (yes and no).

Important predictors were identified using the strategy followed in Collett's text (5). All logistic regression models were checked for the presence of outliers and the need for interaction terms or transformation of variables. Finally, the ability of treating physicians to identify substance use was determined by comparing clinical notes on patients' substance use status with the results of the study's urine screen, which were not given to the clinicians.

Results

Thirty-two of the 93 nonpsychotic patients (34 percent) were identified as substance users by a positive urine drug screen and confirmation. The laboratory test screened for alcohol, benzodiazepines, cannabis, cocaine, opiates, methadone, PCP, propoxyphene, amphetamines, and barbiturates. Patients with DSM-III-R nonpsychotic diagnoses whose current problem was not clinically identified as primarily substance related had higher odds of being female (odds ratio=3.9), of having an adjustment disorder (OR=4.6), of having a history of substance use (OR=3.7), and of reporting use of some substance immediately before visiting the emergency room (OR=4.1).

Of the 32 substance users, most were Caucasian (20 patients, or 63 percent), and most were between the ages of 25 and 44 (20 patients, or 63 percent). Most required no psychotropic medications during the visit (22 patients, or 69 percent) and were not hospitalized. Most of the substance users presented voluntarily for treatment (26 patients, or 83 percent). Users were more likely than nonusers to have some level of suicidality (χ2=3.28, df=1, p=.07).

Clinicians indicated a suspicion of substance use for 35 patients, but their suspicions proved correct in only 14 of the 35 cases, or 40 percent. Among the 58 patients whom clinicians did not suspect of concurrent use, 18 patients were identified as users by the urine test. Physicians failed to pursue the clinical contribution of substance use most often among the patients diagnosed with adjustment problems. Of the 36 patients with adjustment disorders, 19 were found to have used substances, and physicians failed to pursue these findings with 13 of them (68 percent).

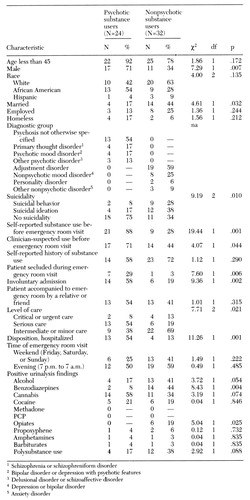

These results were compared with findings from similar analyses for a group of psychotic concurrent substance users in the same emergency room (2). The comparisons are presented in Table 1. Significant differences between these two groups of substance users (p<.05) were found in gender, marital status, level of suicidality, self-report of use, clinician's suspicion of use, use of seclusion during the emergency room visit, admitting status, level of care received, and disposition. Significantly more nonpsychotic patients tested positive for benzodiazepines and opiates, and this group also exhibited increased use of alcohol or multiple substances. In contrast, psychotic patients tended to use cannabis more frequently.

Discussion and conclusions

Psychotic and nonpsychotic patients whose urine tested positive for substances of abuse but who were not clinically diagnosed as acutely intoxicated were distinct from each other in a variety of ways. No recent comparable analyses of similar groups in the emergency room or related treatment settings are available for comparison, although adjustment disorder has been associated with concurrent substance use in some patient groups presenting in acute care psychiatric facilities (6,7). The association between concurrent substance use and an increased level of suicidality in this population is also consistent with other findings (7). Finally, as noted elsewhere (2), the profile of psychotic substance users modeled from these data was found to be consistent with a number of recent reports, suggesting that the sample studied is typical of patients found in many acute care settings.

In this study concurrent substance use among patients in the emergency room was more prevalent among nonpsychotic patients than psychotic patients. Thirty-four percent of nonpsychotic patients tested positive, compared with 21 percent of psychotic patients. Nonpsychotic substance users were most typically females who admitted use immediately before visiting the emergency room and who also acknowledged a history of use but whose visit was conceptualized by treating physicians as being prompted by adjustment difficulties. Such a diagnostic label represents quite minimal psychopathology by psychiatric emergency room standards, where the staff is constantly prepared for the intensive care and hospitalization frequently required by the psychotic patient who is concurrently using substances.

Despite the high prevalence of substance use among these patients, clinicians often failed to pursue substance use as a factor contributing to the condition of nonpsychotic patients, as indicated by their failure to document this possibility in records and to order confirmatory laboratory tests. Clinicians explored the nonpsychotic patient's substance use in only 38 percent of cases, whereas 70 percent of psychotic patients were evaluated for substance use.

Explanations for clinicians' high rate of failure to explore possible substance use among nonpsychotic patients may include a general lack of clinical appreciation for the extent of substance use among such patients or an intentional decision not to explore possible substance use when treating these patients in a psychiatric emergency room. Future research may shed light on this issue by examining the clinical situation and decision-making process in such cases. Meanwhile, considering the consequences of concurrent substance use for patients with mental disorders (3), these results support use of urine drug screening as a routine procedure during evaluation of psychiatric patients in the emergency setting, especially in a nonpsychotic population.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by Mental Health Connections, a partnership between Dallas County Mental Health and Mental Retardation and the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Funding was received from the Texas State Legislature and the Dallas County Hospital District. The research was also partly supported by grants MH-41115 and MH-53799 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Linda Akers, M.S., and Vitauts Jurevics, M.S., for assistance in performing the drug assays and preliminary data analysis; Peggy Rose for data entry services; and Kenneth Z. Altshuler, M.D., and Maurice Korman, Ph.D., for administrative support.

Dr. Gilfillan is assistant professor and Dr. Rush is professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Dr. Claassen is assistant professor in the division of psychology, Dr. Orsulak is professor in the departments of psychiatry and pathology, and Dr. Carmody is a statistician in academic computing services at the medical center. Dr. Gilfillan is also director of psychiatric emergency services at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, where Dr. Claassen is a clinical psychologist, and Ms. Sweeney is a social worker. Dr. Orsulak is also technical director of the toxicological laboratories in the Veterans Affairs North Texas Health Care System. Dr. Battaglia is a consultant to the Alaska Division of Mental Health. Send correspondence to Dr. Claassen at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75235-9070 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychotic and nonpsychotic patients in an emergency room whose recent substance use was confirmed by a laboratory test

1. Currier GW, Serper MR, Allen MH: Diagnosing substance abuse in psychiatric emergency service patients. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 67:57-63, 1995Google Scholar

2. Mirin SM, Weiss RD: Substance abuse and mental illness, in Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders. Edited by Frances R, Miller S. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Fanner ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Claassen C, Gilfillan S, Orsulak P, et al: Substance use among patients with a psychotic disorder in a psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 48:353-358, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Collett D: Modeling Survival Data in Medical Research. London, Chapman & Hall, 1994Google Scholar

6. Galanter M, Castaneda R: Studies of prevalence of dual diagnosis in psychiatric practice, in Dual Diagnosis in Substance Abuse. Edited by Gold MS, Slaby A. New York, Marcel-Dekker, 1991Google Scholar

7. Szuster RR, Schanbacker BL, McCann SC: Characteristics of psychiatric emergency room patients with alcohol- or drug-induced disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1342-1344, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar