Special Section on the GAF: Selection of Outcome Assessment Instruments for Inpatients With Severe and Persistent Mental Illness

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to describe a procedure to assist in selecting outcome measures for inpatients treated at a state psychiatric hospital. The procedure combines evidence-based criteria from the literature, instruments shown to be sensitive to change in clinical trials, and the perspectives of a multidisciplinary team of researchers, administrators, providers, and patient advocates. Recent efficacy and effectiveness studies were used to identify recurrently used outcome instruments. A computerized search of more than 30 bibliographic databases, such as PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Social SciSearch, and ERIC, was conducted for articles published between 1990 and 2002. Comparisons of the most frequently used instruments were made on seven criteria proposed as best-practice indicators, including sensitivity to change and robust psychometrics. The sample produced 110 measures. Rater-completed instruments were represented more often than patient-completed ones. However, considerable variability across both methods was found on the criteria. The limited resources associated with publicly funded inpatient facilities led to a recommendation to select at least one rater-completed and one patient-completed instrument.

In 2000, national health care expenditures were approximately $1.3 trillion, with a projected twofold increase by 2010 (1). More than 7 percent of this amount was for mental health care, totaling an estimated $91 billion (2). To curb this alarming increase in costs and to ensure high-quality care, a greater emphasis on treatment accountability emerged from legislative and accreditation bodies, public agencies, and consumers (3,4,5). In this "age of accountability," it is becoming standard practice for mental health providers to implement outcome management programs to understand the relationship between services, cost, and patient change (6,7). Such programs require instruments that are standardized, psychometrically sound, easy to use, practical, and available at a low cost (6,7,8,9,10).

Those who are interested in using outcome management are met with a cornucopia of possibilities. As Hermann and colleagues (11,12) note, more than 50 stakeholders have proposed more than 300 measures for quality assessment, leading some to recommend common measures or methods (13,14,15,16). A vital distinction to maintain as one enters this literature is Donabedian's tripartite framework (17), which categorizes quality assessment into measures of structure, process, and outcome.

Measures that assess the process of health care delivery are plentiful and have received more attention than outcome measures (11). This level of attention has been attributed to the lower cost of process measures and their ability to provide quick feedback to administrators and clinicians (18,19). However, measures of outcome may be a more direct indicator of quality than either structure or process (20). Moreover, recent advances in computerized outcome management systems now provide the same real-time feedback that was once the domain of process measures (21,22,23). Ellwood (24) opined that outcome measures empower psychiatrists' management of patient care. Others have suggested, "Psychiatrists and mental health care administrators who use outcome assessment to study and apply principles of continuous quality management daily will probably experience better efficiency, greater effectiveness, lower costs, and more satisfied patients" (18).

The fact that outcome assessment receives less frequent attention may also be due to confusion surrounding definitions (25), coupled with the enormous number of measures available from which to select (26). One promising method for dealing with the bewildering number of outcome measures is to restrict focus to measures that are designed for the target patient population. Unfortunately, clinical reality often demands that the target population be defined beyond a single diagnosis or grouping, such as depression or mood disorder. For example, Erbes and colleagues (27) evaluated and recommended outcome instruments for a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital, necessarily considering a broad range of diagnoses. In this article we focus on psychiatric inpatients with diagnoses of severe and persistent mental illness and propose a similar method.

Outcome assessment with psychiatric inpatients

Persons with diagnoses of severe and persistent mental illness have been considered a difficult population to track from an outcomes perspective (28,29). The terms "severe" and "persistent" have been operationalized as "functional limitations in activities for daily living, social interaction, concentration, and adaptation to change in the environment" and likely to "last for 12 months or more," respectively (30). These patients number between one and five million; have diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, autism, or obsessive-compulsive disorder; and cost health care systems billions annually (31).

Despite the extensive impact on resources and the increasing focus on accountability, active debate persists about which outcome measures to use with this patient population. Several studies have evaluated the utility and effectiveness of individual measures (32,33,34,35,36), whereas others have focused on comparisons between a limited number of instruments (37,38,39,40,41). Still, little consensus exists on which measures to select. Particular challenges include norms that provide interpretive meaning, sensitivity to change among patients who are expected to demonstrate little improvement, and robust psychometrics needed to capture subtle patient change.

If an outcome measure succeeds in addressing these challenges, it must also meet a reasonable standard of clinical utility by minimizing time devoted to data collection and other direct costs. This article focuses on the challenges associated with selecting an outcome measure. A companion paper in the State Mental Health Policy column of this issue of Psychiatric Services (42) addresses pragmatic aspects of implementing an outcome management program in a large state-run psychiatric hospital.

Overview of framework for selection

Although a host of resources for selecting quality measures are available (6,11,14,18,43,44), their direct applications pose complex challenges. Accordingly, we propose and illustrate an approach that was used to guide a multidisciplinary work group at a state psychiatric hospital in its selection of outcome measures (see the box on this page). We do not presume to evaluate the enormous number of outcome measures (26), nor are we recommending a specific set of measures. Rather, we describe a method that proved fruitful in our evaluation of a myriad of recommendations and measures.

A proposed method for selecting outcome measures for inpatients with severe and persistent mental illness

Step 1: Identify the patient population targeted for outcome assessment

Step 2: Identify relevant outcome measures by tabulating those used in randomized clinical trials and effectiveness studies treating the targeted patient population

Step 3: Identify a finite and manageable number of selection criteria focused on restrictions of the setting (for example, resources), accuracy of the decision to be made, and the target patient population

Step 4: Evaluate each outcome measure on the criteria by using standards that match available resources

Step 5: Select one or more outcome measures

The first step is to identify the targeted population. This step is critical in the evaluation of instruments, because many instruments have not been extended or tested with distinct patient populations—for example, norms, construct validity, and sensitivity to change have not been established. Invariably, the number of instruments is reduced at step 1. Step 2 further limits the universe of instruments by considering measures that are repeatedly used in efficacy or effectiveness studies with the targeted population. This step has obvious advantages and disadvantages. Advantages include the increased probability of selecting measures that will successfully capture change in a targeted population. Indeed, average change across studies on a measure can be quantified by using a pre- to posttreatment effect size. This metric provides one index for comparing sensitivity to change that is useful given that instruments vary on sensitivity to change (44), especially when used with different populations (45). An average effect size also provides clinicians with a baseline with which to benchmark expectations for patient gains.

The empirical filter in step 2 has notable disadvantages. If widely employed, this filter could lead to stagnation in the field by discouraging the use of promising new instruments. However, older measures that have presumably survived the test of time often serve as the standard for new instruments. This approach may also underemphasize certain domains, such as functioning, and overemphasize others, such as symptoms. However, our proposal is not intended to balance all potential outcome domains, and we refer readers to other sources (18,46). Rather, our goal was pragmatic—identifying measures that have been successfully used with a target population to capture meaningful patient change.

Step 3 acknowledges the numerous and competing criteria proffered as selection guidelines—for example, broad domain coverage, robust psychometrics, cost, and clinical utility. Indeed, in the illustration that follows, we identified 24 criteria offered by experts. Once again, a pragmatic approach to clinical practice requires a restricted set of criteria that are highly relevant to the clinical setting. A frequently endorsed measure in step 2 may be simply impractical for a particular clinical setting. Thus step 3 criteria temper decision making by considering the clinical setting. Step 4 applies these criteria to the measures uncovered in step 2 and often results in a reordering of the measures that are considered best. A measure that is identified in step 2 as being highly endorsed may drop precipitously in rank after the criteria in step 3 are considered. The integration (step 4) of empirical performance (step 2) and clinical setting (step 3) is the end result of selection (step 5).

Representing multiple perspectives may produce better decisions about outcome systems (6,27). Accordingly, a group of academically based researchers, hospital administrators, mental health care providers, and patient advocates formed a team to use the aforementioned method to select optimal measures for a state hospital. More specifically, our principal aims were to survey treatment studies to identify measures in frequent use for our target population, identify relevant literature-based selection criteria, and review the outcome measures by using the proposed criteria.

Applying the framework to a state hospital

Step 1: identifying the target population

Patients at our facility typically have diagnoses of psychotic illnesses (54 percent have schizophrenia, delusional disorders, or schizoaffective disorders) and mood disorders (23 percent have major depression, bipolar disorder, or dysthymia) (47). Thus outcome measures not directly normed for this population were excluded, a procedure that biased our sample of measures in favor of the target population.

Step 2: survey of relevant literature

Our interest in calibrating our selection process with measures used in efficacy or effectiveness treatment studies led to a computerized search of more than 30 bibliographic databases—for example, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Social SciSearch, and ERIC. This approach yielded nearly 500 citations published between 1990 and 2002 by using the search terms "severe and persistent and mental and ill or SPMI," "severe and mental and ill or SMI," and "schizophrenia and outcome and inpatient." Studies conducted before 1990 were excluded to limit bias toward older instruments, and instruments were not counted more than once if they were used in multiple articles associated with a single investigation.

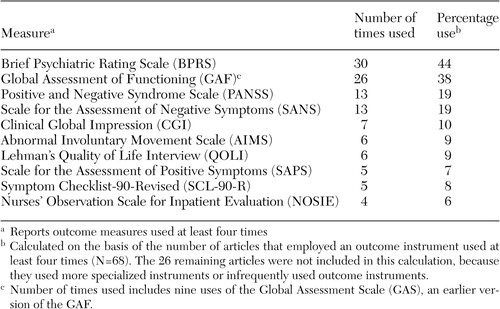

Only 94 citations (20 percent) were treatment evaluation studies that used standardized outcome measures (Table 1). Excluded citations included conceptual or policy papers, reviews, studies of process or structure measures, or nonstandardized outcomes measures—for example, dropout rates, cost, and recidivism. The sample produced 110 measures, with 11 (10 percent) used at least four times, three (3 percent) used three times, 15 (14 percent) used twice, and 81 (74 percent) used just once. Interestingly, 25 measures (23 percent) were investigator created; it has been argued that such measures provide meaningless comparative information (48).

Three observations were drawn from the results of the survey (Table 1). First, the clinician-rated measures that were used most often included the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (49), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (50), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (51), and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (52). The BPRS was used twice as frequently (44 percent) as the PANSS and the SANS.

Second, very few self-report instruments had repeated use. Only two self-report outcome measures surfaced in four or more studies, including the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (53) and the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) (54). Third, multiple-measure assessment was preferred over single-measure protocols by a ratio of 2 to 1. This finding mirrors recommendations that a single source may be less reliable because each source contributes a valid yet potentially divergent perspective (55). Although the average number of measures used per study was 2.8 (range, one to 13), what was striking was the number of studies (N=30) that used a single outcome instrument.

Step 3: selection of criteria

The absence of a standard for selecting outcome instruments led to an integration of criteria suggested by six sources (6,9,10,55,56,57). These experts offer 24 criteria for selecting optimal outcome measures, from which we chose seven on the basis of frequency of endorsement and fit with our setting. In no particular hierarchal order, the criteria were applicability to the target population, availability of training protocol and materials, appropriate norms to ensure interpretability of scores, psychometric integrity (that is, adequate reliability and validity), cost, administration time, and sensitivity to change. Each is discussed more fully below.

Step 4: comparison of frequently used instruments

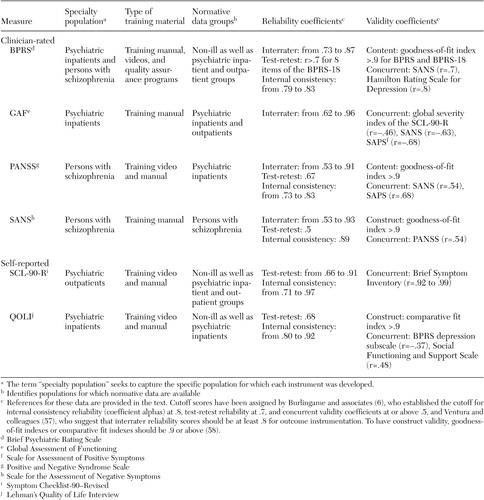

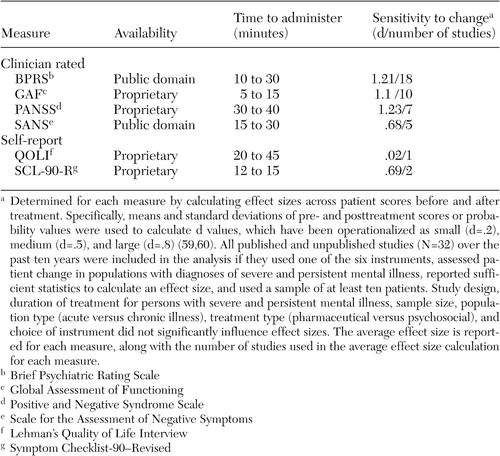

A summary of our evaluation of six of the most frequently used clinician and self-report instruments is presented in Tables 2 and 3 (58,59,60). (This summary is restricted to six instruments because of space limitations.) A brief examination of each measure and greater explication of the seven criteria follow.

BPRS. The BPRS satisfied our target population given that it was created to provide rapid assessments of psychopathology for inpatient populations. Its extensive use in the literature has produced ready-made norms for a variety of populations. There are two revisions of the original 16-item version (49): an 18-item version (61) and a 24-item expanded version (BPRS-E) (62). Each version has produced four similar symptom factors—manic hostility, withdrawal-retardation (negative symptoms), thinking disturbance (positive symptoms), and depression-anxiety—that match typical patient characteristics of state psychiatric hospitals (47).

Clinician-rated scales can provide greater consistency across patients and diagnoses than self-report measures, thereby producing more reliable systemwide evaluations (63). However, this consistency is directly related to the quality of the training material available for ensuring adequate interrater reliability, which is a clear strength of the BPRS (44,57). Indeed, good to moderate interrater reliability is evident (37,64,65), along with moderate test-retest reliability (64) and good internal consistency (65). The literature was also largely supportive of the instrument's construct and concurrent validity (64,66,67,68,69,70). We ranked the clinical utility of the BPRS as high, because it was normed on clinical populations, available at no cost, and very sensitive to change (average d=1.21). Its greatest shortcoming was the resource drain associated with a clinician-rated instrument, an issue addressed in the companion paper in the State Mental Health Policy column in this issue (42).

GAF. As a standard part of the diagnostic protocol (71), the GAF is the most widely used measure of psychiatric patient function (33), with the extant literature providing a wealth of normative data. Introduced as a revised version of the Global Assessment Scale (72), the GAF allows clinicians to rate global patient functioning on a single scale ranging from 1 (persistent danger of severely hurting self or others) to 100 (absence of symptoms to minimal symptoms). Research has reported interrater reliability coefficients that range from modest to excellent (73,74,75,76) as well as moderate to high concurrent validity estimates (76,77). From a clinical utility perspective, the GAF was viewed as comparable to the BPRS, being normed on inpatient and outpatient populations, available at no cost, very quick to administer, and very sensitive to change (d=1.10). As with the BPRS, consistency of ratings requires the implementation of rater training and periodic consistency checks.

PANSS. The PANSS was developed "as an instrument for measuring the prevalence of positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia" (51). It consists of the BPRS-18 (61) plus 12 items from the Psychopathology Rating Scale (78). Clinicians rate patients' symptoms with use of 30 items that aggregate on four scales: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, composite, and general psychopathology. Research has reported evidence of acceptable construct and concurrent validity (79,80), good internal consistency reliability, moderate test-retest reliability (51), and interrater reliability coefficients that range from high to moderate (37,80). Clinical utility was rated lower, because the instrument is lengthier to administer, more costly to use ($32 for a set of 25 questionnaires), and normed on a narrower population. Nevertheless, the instrument appears to be very sensitive to change in our analysis (d=1.23).

SANS. The SANS was developed by Andreasen (52,81) as a measure of negative symptoms among patients with schizophrenia. Clinicians use 30 items that are aggregated on five subscales: affective flattening or blunting, alogia, apathy, asociality, and inattention. This instrument has adequate construct and concurrent validity coefficients (35,80), good internal consistency reliability (52), moderate 24-month test-retest reliability (82), and interrater reliability coefficients that range from moderate to high (52,69,82). The instrument was ranked the lowest because of moderate clinical utility, it was normed on a single population, and it is somewhat lengthy and moderately sensitive to change (d=.68). However, it is available at no cost.

SCL-90-R. Originally designed for use with psychiatric outpatients, the SCL-90-R (53) has enjoyed widespread use in clinical and research settings, producing a wealth of normative data. Patients respond to 90 items that are aggregated on nine symptom dimensions (somatization, obsessive-compulsivity, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism) and three global scales (the global severity index, the positive symptom distress index, and the positive symptom total). Research has shown little evidence of construct validity for this instrument (53,83), although the instrument has shown good internal consistency, test-retest reliability (83,84,85), and moderate concurrent validity with the BPRS (86).

The SCL-90-R was viewed as having moderate clinical utility; being normed on community, outpatient, and inpatient populations; being quick to administer; and being moderately sensitive to change (d=.69). Considerations that lowered its rank were cost ($41 per 50 hand-scored answer sheets) and the fact that it is self-reported among the target population. Self-report measures require less staff time and permit consumer-focused outcome assessment, because patients are empowered to report on their symptoms and expectations about treatment (87). Disadvantages include an insufficient clinical picture as a result of the dependence on patients' ability to accurately describe their condition, which at times is doubtful because of denial, minimization of symptoms, or responder bias (88).

QOLI. The QOLI (51) is a highly structured interview developed to assess current quality of life and global well-being among populations with chronic mental illness. This instrument is made up of objective and subjective questions that allow the patient to rate his or her current situation and satisfaction with life. The QOLI has good construct validity (89,90), moderate concurrent validity (91), moderate test-retest reliability (51), and high internal consistency (92). It was ranked low on clinical utility because of its length, cost (a pay-per-use structure), and low sensitivity to change (d=.02). However, the latter was based on a single study, and norms were available for community and inpatient populations.

Step 5: selecting measures

Clinician-rated instruments clearly outnumbered self-report instruments in our analysis. Lachar and colleagues (67) explained that clinician-rated measures have recently achieved an advantage over self-report in hospitals because of the disabling psychopathology patients now must exhibit to justify hospitalization. The impairment of newly admitted patients negatively affects patients' ability to complete even a brief self-report measure. However, the accuracy of information from clinician-completed measures must be balanced by the resource drain. The BPRS and the GAF require the least time to administer, and the BPRS, the GAF, and the PANSS appear to be equally sensitive to change, yet all instruments required mastery of training materials and demonstrated reliability to produce meaningful information about outcomes.

The team openly acknowledged the limitations of the sample, including a time frame that may have disadvantaged newer instruments—for example, the Multnomah Community Abilities Scales and Outcome Questionnaire. Furthermore, although the frequency count allowed us to easily calibrate against findings in the extant literature, it may have inadvertently excluded potentially useful instruments because of their infrequent use in our sample—for example, the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 and the Addictions Severity Index appeared in two studies each. However, infrequent use portends unknown properties such as sensitivity to change and normative characteristics.

Three issues affected our final recommendations. First, global single-scale assessments, such as the GAF, are frequently used because they are simple to administer and provide immediate feedback (73). However, these scales suffer limitations in accuracy as a result of combining patients' symptoms and functioning in a single rating (93), leading some to question their accuracy with our target population (33,94).

Second, as with most publicly funded facilities, we have limited resources. As a mental health agency focused on improving service delivery from both an organizational and a consumer-oriented perspective (87), we were aware of the considerable discussion about the importance and effectiveness of self-report and clinician-rated instruments (95,96,97,98). At face value, our survey suggests the BPRS and the SCL-90-R as the best clinician-rated and self-report outcome instruments. However, concerns about financial resources, administration time, staff support, staff competence, and training led to active debate. Our adoption of the BPRS led to infrastructure realignment to address these concerns, as detailed in our companion paper (42).

Finally, our survey suggested the SCL 90-R as a self-report tool, but its use raised two concerns: meaningfulness of the outcome data given patient impairment, and cost. When patients are physically unable or unwilling, because of malingering or resistance, to complete a self-report assessment, data may be too erratic (item endorsement at both ends of the range) to facilitate meaningful interpretation. Nevertheless, we adopted an alternative self-report measure because of cost issues, and Earnshaw and colleagues (42) detail how we dealt with data accuracy concerns.

Conclusions

The primary focus of publicly funded facilities is clinical services, with sparse resources available to allocate for outcome assessment. Nonetheless, all of us are faced with evidence-based accountability requirements to demonstrate the effectiveness of clinical services. Outcome measures may provide a valuable supplement to other measures of quality (structure and process) that are more frequently used. The method we used to evaluate extant outcome measures for a target population provides one guide for instrument selection that may prove useful with other target populations. Leveraging against existing clinical trial literature focuses discussion on a limited set of instruments with an estimated sensitivity to change and positively biases discussion on domains and measures that have a proven empirical track record. The proposed method is not without limitations, foremost of which is its empirical versus clinical bias.

Dr. Burlingame, Mr. Dunn, and Mr. Axman are affiliated with the department of clinical psychology at Brigham Young University, 238 TLRB, Provo, Utah 84602 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Chen, Mr. Lehman, Mr. Earnshaw, and Dr. Rees are with the department of psychology at Utah State Hospital in Provo. This article is part of a special section on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

|

Table 1. Most frequently used outcome measures in populations of persons with severe and persistent mental illness

|

Table 2. Evaluation of frequently used clinician-rated and self-reported outcome measures

|

Table 3. Availability, time to administer, and sensitivity to change of frequently used clinician-rated and self-report outcome measures

1. US Census Bureau: Statistical Abstract of the United States. Available at www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/02statab/health.pdfGoogle Scholar

2. Coffey RM, Mark T, King E, et al: National Estimates for Expenditures for Mental Health the Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2000Google Scholar

3. Lyons JS, Howard KI, O'Mahoney MT, et al: The Measurement and Management of Clinical Outcomes in Mental Health. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

4. Mirin S, Namerow M: Why study treatment outcome? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1007–1013, 1991Google Scholar

5. Teague GB, Ganju V, Hornik JA, et al: The MHSIP mental health report card: consumer-oriented approach to monitoring the quality of mental health plans. Evaluation Review 21:330–341, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Burlingame GM, Lambert MJ, Reisinger CW, et al: Pragmatics of tracking mental health outcomes in a managed care setting. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:226–236, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Burlingame GM, Mosier JI, Wells MG, et al: Tracking the influence of mental health treatment: the development of the Youth Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 8:361–379, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Blank MB, Koch JR, Burkett BJ: Less is more: Virginia's performance outcomes measurement system. Psychiatric Services 55:643–645, 2004Link, Google Scholar

9. Newman FL, Ciarlo JA, Carpenter D: Guidelines for selecting psychological instruments for treatment planning and outcome assessment, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment, 2nd ed. Edited by Maruish ME. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 1999Google Scholar

10. Vermillion JM, Pfeiffer SI: Treatment outcome and continuous quality improvement: two aspects of program evaluation. Psychiatric Hospital 24:9–14, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hermann RC, Palmer RH: Common ground: a framework for selecting core quality measures for mental health and substance abuse care. Psychiatric Services 53:281–287, 2002Link, Google Scholar

12. Hermann RC, Leff H, Palmer RH, et al: Quality measures for mental health care: results from a national inventory. Medical Care Research and Review 57:135–153, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Manderscheid R, Henderson M: The field needs to agree on quality measures. Behavioral Health Accreditation and Accountability Alert, Feb 2001, pp 4–5Google Scholar

14. Brook RH: The RAND/UCLS appropriateness method, in Clinical Practice Guideline Development: Methodology Perspectives. Edited by McCormick KA, Moore SR, Siegel RA. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1994Google Scholar

15. McGlynn EA, Kerr EA, Asch SM: New approach to assessing the clinical quality of care for women: the QA tool system. Womens Health Issues 9:184–192, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McGlynn EA: Choosing and evaluating clinical performance measures. Joint Commission Journal of Quality Improvement 24:470–479, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Donabedian A: Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. Ann Arbor, Michigan, Health Administration Press, 1980Google Scholar

18. McGrath BM, Tempier RP: Implementing quality measures in psychiatry: from theory to practice: shifting from process to outcome. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48:467–474, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hermann RC, Finnerty M, Provost S, et al: Process measures for the assessment and improvement of quality of care for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:95–104, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Srebnik D, Hendryx M, Stevenson J, et al: Development of outcome indicators for monitoring the quality of public mental health care. Psychiatric Services 48:903–909, 1997Link, Google Scholar

21. Brown GS, Burlingame GM, Lambert MJ, et al: Pushing the quality envelope: a new outcomes management system. Psychiatric Services 52:925–934, 2001Link, Google Scholar

22. Modai I, Ritsner M, Silver H, et al: A computerized patient information system in a psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 52:476–478, 2002Link, Google Scholar

23. Lambert MJ: Emerging methods for providing clinicians with timely feedback of effective treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61, in pressGoogle Scholar

24. Ellwood PM: Shattuck lecture: outcomes management: a technology of patient experience. New England Journal of Medicine 318:1549–1556, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bachrach LL: Assessment of outcomes in community support systems: results, problems, and limitations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:39–60, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Froyd JE, Lambert MJ, Froyd JD: A review of practices of psychotherapy outcome measurement. Journal of Mental Health 5:11–15, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Erbes C, Polusny MA, Billig J, et al: Developing and applying a systematic process for evaluation of clinical outcome assessment instruments. Psychological Services 1:31–39, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Rowan T, O'Hanlon WH: Solution-Oriented Therapy for Chronic and Severe Mental Illness. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

29. Soreff SM: Handbook for the Treatment of the Seriously Mentally Ill. Kirkland, Wash, Hogrefe and Huber, 1996Google Scholar

30. Rothbard AB, Schinnar AP, Goldman H: The pursuit of a definition for severe and persistent mental illness, in Handbook for the Treatment of the Seriously Mentally Ill. Edited by Soreff SM. Kirkland, Wash, Hogrefe and Huber, 1996Google Scholar

31. Carey MP, Carey KB: Behavioral research on severe and persistent mental illnesses. Behavioral Therapy 30:345–353, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Page AC, Hooke GR, Rutherford EM: Measuring mental health outcomes in a private psychiatric clinic: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales and Medical Outcomes Short Form SF-36. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35:377–381, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Piersma H, Boes J: The GAF and psychiatric outcome: a descriptive report. Community Mental Health Journal 33:35–41, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Piersma HL, Reaume WM, Boes JL: The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) as an outcome measure for adult psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 50:555–563, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Sayers SL, Curran PJ, Mueser KT: Factor structure and construct validity of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Psychological Assessment 8:269–280, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, et al: The Independent Living Skills Survey: a comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:631–658, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Bell M, Milstein R, BeamGoulet J, et al: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:723–728, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Brekke JS: An examination of the relationships among three outcome scales in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:162–167, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R, Xu W, et al: Quality of life in schizophrenia: a comparison of instruments. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:659–666, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Green RS, Gracely EJ: Selecting a rating scale for evaluating services to the chronically mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 23:91–102, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Welham J, Stedman T, Clair A: Choosing negative symptom instruments: issues of representation and redundancy. Psychiatry Research 87:47–56, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Earnshaw D, Rees F, Dunn TW, et al: Implementing a multi-source outcome assessment protocol in a state psychiatric hospital: a case study from the public sector. Psychiatric Services 56:411–413, 2005Link, Google Scholar

43. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2000Google Scholar

44. Maruish M (ed): The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment, 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2004Google Scholar

45. Hill CE, Lambert MJ: Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th ed. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley, 2004Google Scholar

46. Rosenblatt A, Wyman N, Kingdon D, et al: Managing what you measure: creating outcome driven systems of care for youth with serious emotional disturbances. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 25:177–193, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Burlingame GM, Earnshaw D, Hoag M, et al: A systematic program to enhance clinician group skills in an inpatient psychiatric hospital. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 52:555–587, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Bednar R, Burlingame GM, Masters K: Systems of family treatment: substance or semantics? In Annual Review of Psychology, vol 39. Edited by Rosenzweig MR, Porters LW. Palo Alto, Calif, Annual Reviews, 1988Google Scholar

49. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

50. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

51. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Andreasen NC: Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: definition and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:784–788, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Derogatis LR, Cleary PA: Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90: a study in construct validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology 33:981–989, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

54. Lehman AF: A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

55. Ciarlo JA, Brown TR, Edwards DW, et al: Assessing Mental Health Treatment Outcome Measurement Techniques: DHHS pub no 86–1301. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1986Google Scholar

56. Ogles BM, Lambert MJ, Masters KS: Assessing Outcome in Clinical Practice. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn & Bacon, 1996Google Scholar

57. Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, et al: Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: the drift busters. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:221–244, 1993Google Scholar

58. Hu L, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6:1–55, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

59. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112:155–159, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB: Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2001Google Scholar

61. Overall JE: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, in ECDEU Assessment Manual. Edited by Guy W. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

62. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the expanded BPRS. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594–602, 1986Google Scholar

63. Cone JD: Evaluating Outcomes: Empirical Tools for Effective Practice. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001Google Scholar

64. Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): a comprehensive review. Journal Operational Psychiatry 11:49–65, 1980Google Scholar

65. Hafkenscheid A: Psychometric evaluation of a standardized and expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 84:294–300, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, et al: Symptom dimensions in recent-onset schizophrenia and mania: a principal components analysis of the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatry Research 97:129–135, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Lachar D, Bailley SE, Rhoades HM, et al: New subscales for an anchored version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: construction, reliability, and validity in acute psychiatric admissions. Psychological Assessment 13:384–395, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Mueser KT, Curran PJ, McHugo GJ: Factor structure of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in schizophrenia. Psychological Assessment 9:196–204, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

69. Thiemann S, Csernansky JG, Berger PA: Rating scales in research: the case of negative symptoms. Psychiatry Research 20:47–55, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Newcomer JW, Faustman WO, Yeh W, et al: Distinguishing depression and negative symptoms in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 31:243–250, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2002Google Scholar

72. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Hall R: Global Assessment of Functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics 36:267–275, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, et al: A brief mental health outcome scale: reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). British Journal of Psychiatry 166:654–659, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Schwartz RC, Cohen BN, Grubaugh A: Does insight affect long-term inpatient treatment outcome in chronic schizophrenia? Comprehensive Psychiatry 38:283–288, 1997Google Scholar

76. Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, et al: Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1858–1963, 2000Link, Google Scholar

77. Startup M, Jackson MC, Bendix S: The concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). British Journal of Clinical Psychology 41:417–422, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Singh MM, Kay SR: A comparative study of haloperidol and chlorpromazine in terms of clinical effects and therapeutic reversal with benztropine in schizophrenia: theoretical implications for potency differences among neuroleptics. Psychopharmacologia 43:103–113, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V: Psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:473–482, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Norman RM, Malla AK, Cortese L, et al: A study of the interrelationship between and comparative interrater reliability of the SAPS, SANS and PANSS. Schizophrenia Research 19:73–85, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, 1984Google Scholar

82. Schuldberg D, Quinlan DM, Morgenstern H, et al: Positive and negative symptoms in chronic psychiatric outpatients: reliability, stability, and factor structure. Psychological Assessment 2:262–268, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

83. Hafkenscheid A: Psychometric evaluation of the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) in psychiatric patients. Personality and Individual Differences 14:751–756, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

84. Derogotis LR, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine 13:595–605, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Schmitz N, Hartkamp N, Franke GH: Assessing clinically significant change: application to the SCL-90-R. Psychological Reports 86:263–274, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Morlan KK, Tan S: Comparison of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology 54:885–894, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Howard PB, El-Mallakh P, Rayens MK, et al: Consumer perspectives on quality of inpatient mental health services. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 17:205–217, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88. Eisen SV, Leff HS, Schaefer E: Implementing outcome systems: lessons form a test of the BASIS-32 and the SF-36. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:18–27, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89. Uttaro T, Lehman A: Graded response modeling of the Quality of Life Interview. Evaluation and Program Planning 22:41–52, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

90. McNary SW, Lehman AF, O'Grady KE: Measuring subjective life satisfaction in persons with severe and persistent mental illness: a measurement quality and structural model analysis. Psychological Assessment 9:503–507, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

91. Corrigan PW, Buican B: The construct validity of subjective quality of life for the severely mentally ill. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:281–285, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Russo J, Roy-Byrne P, Reeder D, et al: Longitudinal assessment of quality of life in acute psychiatric inpatients: reliability and validity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:166–175, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Phelan M, Wykes T, Goldman H: Global function scales. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:205–211, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Moos R, McCoy L, Moos B: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ratings: determinants and role as predictors of one-year treatment outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56:449–461, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Hoyt WT: Rater bias in psychological research: when is it a problem and what can we do about it? Psychological Methods 5:64–86, 2000Google Scholar

96. Baigent L, Ostbye T, Femando MLD: Feasibility of client reports to measure treatment outcome in schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:94–95, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

97. Hamera EK, Schneider JK, Potocky M, et al: Validity of self-administered symptom scales in clients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Schizophrenia Research 19:213–219, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Rogers R: Clinical Assessment of Malingering and Deception, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar