One-Year Follow-Up of Persons Discharged From a Locked Intermediate Care Facility

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study examined outcomes during a one-year follow-up for persons who were discharged from a locked intermediate care facility in an urban area in California. The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which persons with severe mental illness can be successfully transferred from an intermediate care facility to lower levels of care. METHODS: A total of 101 persons consecutively discharged were studied by record review and by obtaining information from facility staff members, therapists, case managers, and other community caretakers. RESULTS: During the follow-up period 56 percent of the patients who were discharged from the intermediate care facility were not able to demonstrate even minimal functioning in the community. These persons spent 90 or more days in locked or highly structured institutions that provided 24-hour care (including jail) or had five or more acute hospitalizations. However, 44 percent spent less than 90 days in these institutions and had fewer than five acute hospitalizations. Thirty-three percent were not known to have spent any time in an institution or hospital. CONCLUSIONS: The high rate of recidivism shown in this cohort suggests that the current emphasis on transferring patients from more structured, intermediate inpatient services to lower levels of care is not effective for a majority of patients. Furthermore, the poor clinical outcomes found in this cohort did not seem to be offset by any reduction in overall governmental costs because of the high use of acute and intermediate hospitalization and the costs of the criminal justice system.

Institutes for mental disease (IMDs) in California are locked, private community intermediate care facilities with a high degree of structure, although they are less structured than state hospitals (1). Generally, residents of IMDs are persons who have severe mental illness, have been considered by referring facilities to present problems in treatment and management that are too difficult for a less structured level of care to handle, and have been placed there by their conservators. In California, a Lanterman-Petris-Short Act (LPS) conservatorship is granted for persons who are found by the court to be gravely disabled—that is, persons who are unable to provide for their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter because of mental illness (2,3).

In recent years, as fiscal shortages have beset state and local mental health authorities, the relatively large per diem costs of state hospitals (approximately $360 a day for long-term patients in California) have been seen as expenses that could be cut in order to fund community programs. As of December 2004 California had fewer than two state hospital beds per 100,000 population, not including forensic beds (4). With the greatly decreased number of state hospital beds, an increasing state population, and no alternative facilities that are highly structured, except for jails and prisons, the tendency throughout California has been to place individuals who have the most difficult problems in treatment and management in IMD beds. As of October 2003 California had 47 such facilities with a total of approximately 4,300 beds (5). Even these less expensive beds (per diem cost of $112.92 as of August 1, 2003) have been viewed as a cost that could be cut. Thus 24-hour, structured care for extended periods has become much less available to persons with long-term, severe mental illness. Because of this shortage there has been ongoing pressure from states and counties to discharge patients, at times prematurely, from state hospitals and IMDs to the community in order to make room for other persons with severe mental illness who are waiting to enter these facilities.

The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of patients discharged from an IMD and determine their outcomes one year after discharge in terms of the number of days spent during the follow-up year in acute hospitals, IMDs, and jail. This study determined the extent to which persons with severe mental illness can be successfully transferred from facilities with intermediate levels of care and structure to lower levels of care.

Methods

Setting

The facility studied was a 95-bed locked IMD in Los Angeles County. The IMD is generally held in high regard by mental health professionals and is owned and administered by a person who is also an active member of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. The facility provides very close medication supervision; approximately three-fifths of the patients receive their medication in either liquid or crushed form. Clozapine is prescribed when other antipsychotics prove ineffective (more than 20 percent of the study group were taking clozapine). The staff-patient ratio is high, with 45 full-time nursing staff members, 18 of whom are licensed (registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and psychiatric technicians); three part-time psychiatrists; and 14 program staff members who provide at least 27 hours of activities every week for each patient. Activities include group therapies, therapeutic social and recreational activities, and instruction in activities of daily living.

Procedure

This study was approved by the human subjects research committee of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. Data were collected by key members of the facility and by the senior author. We selected 108 consecutive discharges from July 2000 to July 2002. However, we were able to obtain information for only 101 of these persons at the one-year follow-up.

The human subjects research committee gave permission to use clinical records from the facility, information from the computerized information system at the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, and information obtained from talking with staff at the IMD and at facilities of the Department of Mental Health, including contract agencies. Because the research committee was concerned about maintaining the confidentiality of individuals placed on LPS conservatorship, permission was not given to seek information from persons in the study sample, their relatives, or their therapists who work in private practice.

Demographic information, diagnoses, and social and psychiatric history were collected. The outcome variables were the number of days spent in acute hospitals, IMDs, and jail and the number of acute psychiatric hospitalizations during the follow-up year.

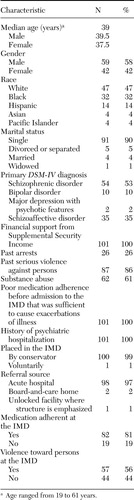

Results

Characteristics of the study sample are given in Table 1. The median length of stay in the IMD for the 101 persons was 196 days, ranging from 22 to 1,254 days.

Ninety persons in our study (89 percent) had discharge plans that were formulated by the facility with the patient, the conservator, and the case manager. All discharge plans provided for follow-up mental health treatment, including medications and case management. Of the 90 persons with discharge plans, 58 persons (64 percent) were placed in board-and-care homes, 19 persons (21 percent) with family members, nine persons (10 percent) in special highly structured unlocked facilities, one person (1 percent) in a supervised apartment, one person (1 percent) with a friend, one person (1 percent) in a skilled nursing facility because of serious physical problems, and one person (1 percent) in another IMD.

Eleven persons (11 percent) did not have planned discharges. Eight of these persons (73 percent) were sent to acute hospitals (six for assaultive behavior and two for strong suicidal tendencies) because the IMD believed that it could not manage them; none of these patients returned to the IMD. The remaining three patients (27 percent) left the facility when their LPS conservatorships were not renewed. These patients refused all placements at follow-up; two lived on the streets, and one lived in a hotel.

Outcomes

One person died during the one-year follow-up period. Of the remaining 100 persons, 46 spent more than 90 days in locked or highly structured institutions that provided 24-hour care, that is, acute psychiatric hospitals, IMDs, or jail. Of these 46 persons, 31 spent at least half the year (181 to 365 days) in these institutions. An additional three spent the year in special unlocked facilities where their movements and activities were greatly restricted and much emphasis was placed on structure. An additional seven persons had five or more acute hospitalizations. Thus, during the follow-up period, 56 persons spent more than 90 days in locked or highly structured institutions that provided 24-hour care or had five or more acute hospitalizations.

Forty-four persons spent less than 90 days in locked or highly structured facilities that provided 24-hour care and had less than five acute hospitalizations. Of these 44 persons, 21 lived with family members, 22 lived in board-and-care homes, and one lived in her own apartment. Moreover, 33 of the 44 persons were not known to have spent any days in locked or highly structured institutions that provided 24-hour care and, from what we could learn, lived stable lives in the community.

During the one-year follow-up, 12 persons in the study sample (12 percent) were known to have been arrested and three persons (3 percent) were known to have been homeless.

Discussion

Deinstitutionalization, in California and throughout the nation, remains an ongoing process. Persons with severe mental illness who present difficult problems in treatment and management continue to be placed in the community. Follow-up data are needed to assess this practice.

Persons in our study had severe problems in treatment and management and were referred to the IMD because of the clinical judgment that they could not be managed in lower levels of care, such as in board-and-care homes or with family members. These persons tended to be single, have a major psychotic or mood disorder, and rely on public monies for their financial support. In addition, they had a history of physical violence against persons, substance abuse, poor medication adherence before they were admitted to the IMD, and previous psychiatric hospitalizations.

During the one-year follow-up, 56 percent of the sample had numerous acute psychiatric hospitalizations or spent lengthy periods in facilities where their movements and activities were greatly restricted and where emphasis was placed on structure. Mental health professionals who treated them related that when these persons were in the community during the follow-up year, they tended to lead chaotic and dysphoric lives, often had severe interpersonal conflicts, and presented serious problems in treatment. Thus it appears that a large percentage of individuals in our study were not ready for a lower level of care, even though 89 percent had a treatment plan formulated and efforts made to implement it before they were discharged from the IMD.

On the other hand, almost half the sample (44 percent) spent less than 90 days in locked or highly structured institutions that provided 24-hour care, had fewer than five psychiatric hospitalizations, and lived in board-and-care homes, with their families, or on their own. As far as we could learn, their lives tended to be stable. These persons lived in open settings, and most were not known to have spent any days in acute hospitals, IMDs, or jail.

Discharges from higher levels of care, such as IMDs, are often driven by the desire to lower costs as well as an ideology that highly structured care is seldom needed. Almost half the study sample did well after being discharged from the IMD and thus represented a savings to the mental health system in terms of treatment costs. However, more than half the sample did not have a favorable outcome. It appears that discharging patients prematurely, with community resources that in many cases could not provide the necessary level of structure, may have cost as much, if not more, in terms of repeated acute inpatient hospitalization, care in IMDs, and psychiatric care in the criminal justice system. In addition, discharging patients prematurely can lead to social costs, such as the disruption of the lives of the patients and their families.

This study has limitations. On the basis of anecdotal reports it would appear that the outcomes of patients who left the IMD in our study were similar to those of patients at IMDs throughout California. However, we do not have comparable data from these facilities. Moreover, because we were not permitted to talk with the persons with mental illness, their families, or their private therapists, we were greatly limited in our knowledge about the character and quality of these persons' lives during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

This study showed that many persons with severe mental illness can live successfully in the community after a period of highly structured care in an IMD. Conversely, the study also showed that despite a median length of stay at the IMD of 196 days, more than half the sample could not be released into the community without necessitating numerous or lengthy psychiatric hospitalizations and periods in IMDs, becoming involved in the criminal justice system, or living on the streets. However, it is possible that the availability of more outpatient mental health resources, such as assertive community treatment, might have increased the number of persons who had a favorable outcome in the community.

Clearly, we failed to properly serve persons who did not do well after being discharged, as so often happens with those whose illnesses are most severe. Individuals with serious mental illness need to be given the level of care and structure that they require, for as long as necessary, so they can attain stability and enhance their quality of life. Some believe that a subgoup of persons with long-term severe mental illness needs highly structured, 24-hour care, often in locked facilities for intermediate or long periods (6,7,8,9,10). As Fisher and colleagues (9) stated in 1996, "Our data suggest that an ever broader spectrum of persons with severe mental illness can be managed in the community as more community-based and alternative inpatient settings are created to meet their needs. But the most difficult populations remain, and they appear resistant to permanent exclusion from the state hospital, even in the best-funded community systems." As our findings suggest, if we are to provide an appropriate level of care for persons with severe mental illness, there should be community resources that are more effective and further study on the extent to which 24-hour highly structured care and treatment in hospitals and intermediate care facilities is needed.

Dr. Lamb is professor of psychiatry and director of the division of mental health policy and law and Dr. Weinberger is professor of clinical psychiatry and chief psychologist at the Institute of Psychiatry, Law, and Behavioral Sciences at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California School of Medicine in Los Angeles. Send correspondence to Dr. Lamb at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Southern California, P.O. Box 86125, Los Angeles, California 90086-0125 (email, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 101 persons discharged from an institute for mental disease (IMD)

1. Lamb HR: The new state mental hospitals in the community. Psychiatric Services 48:1307–1310, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. California Mental Health Services Act. Sacramento, California Health and Welfare Agency, 1974Google Scholar

3. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Conservatorship for gravely disabled psychiatric patients: a four-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:909–913, 1992Link, Google Scholar

4. Weekly Report on State Hospitals Serving the Mentally Ill. California Department of Mental Health, Long-Term Care Branch, Sacramento, Dec 15, 2004Google Scholar

5. Facilities and Programs Licensed or Certified by Department of Mental Health Designated as Institutions for Mental Disease (IMDs). DMH Letter No 02–06. Sacramento, California Department of Mental Health, Sacramento, 2003Google Scholar

6. Appleby L, Desai PN, Luchins DJ, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72–76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

7. Talbott JA, Glick ID: The inpatient care of the chronically mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:129–140, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Spaulding WD: State hospitals in the twenty-first century: a formulation. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 84:113–122, 1999Google Scholar

9. Fisher WH, Simon L, Geller JL, et al: Case mix in the "downsizing" state hospital. Psychiatric Services 47:255–262, 1996Link, Google Scholar

10. Bachrach LL: The state of the state mental hospital at the turn of the century. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 84:7–24, 1999Google Scholar