Blood-Borne Infections and Persons With Mental Illness: Responding to Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

The Five-Site Health and Risk Study estimated prevalence rates of blood-borne infections, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C, and addressed risk factors and correlates of infection among persons with severe mental illness. In this final article of the special section in this issue of Psychiatric Services, the authors review public health recommendations and best practices and discuss the implications of these results for community mental health care of clients with severe mental illness. Standard public health recommendations could be modified for use by community mental health providers. In addition, expansion of integrated dual disorders treatments and improving linkage with specialty medical care providers are recommended.

The articles in this special section of Psychiatric Services address the problem of blood-borne infections, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C, among persons with severe mental illness. Given the high rates of risk behaviors and infections in this patient population, what should be done to provide optimal prevention and treatment? In this final article of the special section, we review public health recommendations and best practices and discuss the implications of these results for community mental health care of clients with severe mental illness.

Current prevention and treatment recommendations

Despite greater awareness of infectious diseases, a majority of community mental health providers do not adequately address chronic infectious disease issues among persons with severe mental illness (1,2,3). Several experts have commented on the need for public-sector mental health systems to address infectious disease in this population (4,5).

We begin with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's recommendations for key services for addressing the problem of elevated risk for hepatitis (6,7,8,9). These recommendations are to screen for substance use and sexual risk behaviors; to test for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C infection; to immunize against hepatitis A and B; to provide risk-reduction counseling and substance abuse treatment; and to refer and support infected clients for medical assessment and treatment. Last we discuss the need to integrate mental health care with substance abuse treatment and with general medical care.

Screening for risk behaviors

The most common risks of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness are drug use behaviors, such as sharing drug paraphernalia, and sexual behaviors related to drug use, such as having unprotected sex with high-risk partners (10,11,12). As Osher and colleagues (13) point out in this issue of the journal, intravenous drug use and crack cocaine use confer the highest risk of infection. Community mental health providers should screen clients for these risk behaviors. Because high-risk behaviors are often illegal—for example, injecting drugs—stigmatizing, or sources of personal shame, clinicians can be uncomfortable asking clients about them. In addition, clients are likely to underreport these behaviors. Computer-assisted interviewing may mitigate these problems, because rates of disclosure for illegal or stigmatized behaviors appear to be higher on self- or computer-administered questionnaires (14,15,16,17,18).

Testing at-risk clients

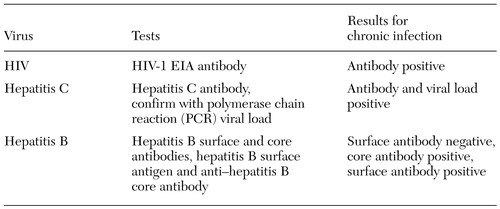

Persons who report risk behaviors for HIV or hepatitis infection should be tested (6). Recommended tests, which can be obtained in a single blood draw, and results indicating chronic infection are summarized in Table 1. Testing also involves pre- and posttest counseling about test procedures and the implications of test results.

Immunization

Safe and effective vaccines can prevent infection with both hepatitis B and hepatitis A, which can cause fulminant hepatitis among persons infected with hepatitis B or C. Currently no vaccine exists to prevent hepatitis C or HIV infection. The vaccines for hepatitis A and B can be delivered together in one injection (19,20). For full immunity, three doses of the combined vaccine administered over six months are recommended. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that anyone who engages in unsafe sex or risky drug use should receive the vaccines.

If a client subsequently tests positive for hepatitis B, completing the vaccination series for hepatitis B is unnecessary. However, the vaccine series for hepatitis A should be completed, and there is no medical contraindication to completing the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine series. Persons who test positive for HIV or hepatitis C should complete the vaccination series for both hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Those who test negative for all infectious diseases but engage in risk behaviors should still complete the immunization series.

Experts believe that drug users in the general population are difficult to vaccinate because they are hard to access, and studies of adherence to vaccination among intravenous drug users have had mixed results (21,22). However, experience with patients who have severe mental illnesses suggests that compliance with vaccination is more likely to be achieved if immunization is integrated with standard case management and offered on-site at the usual source of care for these clients. An investigation currently under way in New Hampshire shows that a trained community mental health nurse can effectively provide education, draw blood to test for infectious diseases, and immunize against hepatitis during a single half-hour visit to a mental health center (23).

Risk reduction

Risk reduction refers both to helping persons who are at risk but not yet infected to reduce risk behaviors and helping those who are infected to reduce behaviors that endanger others. Empirically tested, effective approaches to risk reduction for infectious diseases usually include four to six sessions of counseling to provide information, enhance self-management skills, enhance self-efficacy, and develop social supports and reinforcement for behavior change (24). Cognitive-behavioral HIV risk-reduction groups have been developed or adapted specifically for persons with severe mental illness and have demonstrated efficacy in controlled clinical trials (25,26,27,28). It is important to note that most existing interventions do not target drug-risk behaviors and are therefore not likely to have an impact on the more prevalent problem of hepatitis C, which is most commonly spread through drug-risk behaviors. Integrated treatment for co-occurring substance use disorders and mental illness may be a more direct intervention to reduce the risk of hepatitis C.

Given the current evidence, mental health clinicians should begin by providing clients with individual counseling to help them develop motivation and skills to reduce HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C risk behaviors. Understanding the dangers of these infectious diseases may help clients become interested in learning how to avoid using drugs, but information alone is usually not enough. Studies of integrated treatment for dual diagnoses (severe mental illness and a comorbid substance use disorder) show that clients are more likely to change drug use behaviors if they find safe housing, have relationships with clean and sober friends, engage in meaningful daytime activities, and receive regular counseling and case management (29,30).

Medical evaluation and treatment

If a client tests positive for one of these blood-borne infectious diseases, the client needs to be referred for medical evaluation by a medical specialist or specialty team. Treatment of HIV infection is now recommended for nearly all infected persons. Treatment of hepatitis C and hepatitis B with medication may be recommended for persons with a moderately severe infection as assessed by examination, laboratory tests, and, in some cases, liver biopsy. Infected persons, even if they are not receiving treatment, should be followed yearly by a medical specialist.

HIV treatment. Antiretroviral treatment of patients infected with HIV is a rapidly evolving field. Many aspects of antiretroviral therapy have been incorporated into treatment guidelines (31) used by HIV specialists.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is now recommended for patients who are symptomatic from HIV infection or whose laboratory examinations indicate a compromised immune system (for example, CD-4 counts). Typical first-line HAART regimens include three antiviral medications. The primary goal is to completely suppress viral replication, resulting in reduction of HIV viral load in serum to undetectable levels over a period of months. The second goal is subsequent immune restoration as the CD-4 count increases over a period of months to years. The most important predictor of long-term efficacy with HAART is the patient's adherence to the prescribed regimen.

Treatment of hepatitis B or C. The standard of care for the antiviral treatment of hepatitis B and hepatitis C—both whom to treat and with what medication regimen—is rapidly changing. The current standard for the treatment of hepatitis B infection is with either subcutaneous alpha-interferon or oral lamivudine over six to 12 months. The current standard for the treatment of hepatitis C is the pegylated version of alpha-interferon, administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection, in combination with ribavirin, administered orally in tablet form twice a day. This treatment is currently the most effective—approximately 50 percent of patients experience eradication of all virus (30 percent to 70 percent, depending on patient and viral characteristics) (32,33,34).

The most common adverse events observed with interferon include fever, nausea, and injection-site reaction; the most severe are blood dyscrasias. The side effects are more likely to occur with high dosages of medication and longer duration of treatment, and they resolve rapidly when the medication is discontinued. Patients are more likely to respond to treatment if their liver disease is less severe, they have lower amounts of virus in their blood, they abstain from alcohol, and they are infected with viral subtypes other than hepatitis C subtype 1b.

Adverse effects. Clinicians have been reluctant to prescribe interferon to persons with severe mental illness and hepatitis B or C infection because of concerns about potential psychiatric and cognitive side effects (depression and memory loss) as well as questions about the ability of these patients to withstand other common side effects, including flu-like symptoms, fatigue, and malaise (35). Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends treatment for clients with severe mental illness if their illness is stabilized or in full remission (36).

Studies of the use of antiviral medications among persons with psychiatric disorders have had mixed results regarding the prevalence and tolerance of psychiatric side effects (37,38,39). Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics, effectively prevent interferon-related depression and cognitive slowing in many cases but have not been studied among persons with severe mental illness (40). However, the feasibility and safety of treating these clients with antiviral medications such as interferon in the context of careful symptom monitoring have been demonstrated (41). Hauser and colleagues (40) reported that they achieved high rates of hepatitis treatment adherence in a psychiatrically impaired group by using a more assertive approach to psychiatric management, including optimization of psychiatric treatment before initiating interferon, close monitoring, and adjustment of psychiatric medication to address the psychiatric side effects of antiviral medications.

Medication interactions. Prescribers of psychotropic medications need to be aware of the potential for interactions between medications used to treat infectious diseases and those used to treat psychiatric illness. The interactions of concern for treating persons who are taking medication for HIV are summarized in the recent American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Patients with HIV/AIDS (42). Clinicians should refer to the APA guidelines at www.psych.org/clin_res/hivaids32001.cfm. Guidelines are also summarized elsewhere (43).

Treatment adherence. Persons with dual disorders can be difficult to engage and retain in treatment (44,45,46) and may have difficulty with medication adherence (47). However, Walkup and colleagues (48) found that HIV-infected persons with schizophrenia and affective psychoses were as likely to be enrolled in treatment with HIV antiretrovirals as other HIV-infected persons and were adherent to antiretrovirals for longer periods than those without schizophrenia. Given that HIV treatment is as complex and burdensome as treatment for hepatitis C infection, the results of this study suggest that persons with severe mental illness should be able to participate in hepatitis treatment.

Financing. Given the high cost of illness burden and treatment of hepatitis B and C, hepatitis screening and vaccination programs for high-risk groups make sense (49) and are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (50). Persons with severe mental illness are usually entitled to and have Medicaid insurance, which can pay for tests and vaccinations, which cost approximately $80 and $90, respectively. No studies of cost-effectiveness of screening and testing have been published for persons with severe mental illness, but given the high rates of hepatitis, prevention programs could be cost-effective compared with the cost of care and treatment of persons who develop chronic hepatitis. Although treatment of hepatitis C infection with medications is costly, treatment of the illness and its complications over the longer term is also costly. Studies that model treatment of persons with hepatitis C in the general population by using interferon-alpha alone and in combination with ribavirin indicate that the treatment is cost-effective from a societal perspective (51,52).

Implications for service development

The research findings and public health recommendations described above must be considered in future plans for public mental health services. As we move ahead to develop and test specific interventions for persons with severe mental illness, two overarching service system issues must be addressed. First is the need to prioritize effective substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Second is the equally pressing need for effective medical care, including prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, for people with severe mental illness. Access to effective substance abuse and medical treatments, both worthwhile goals in their own right, must be accomplished if progress is to be made in addressing the hepatitis epidemic in this patient population.

Substance abuse treatment

The collaborative study reported in this special section (11) and elsewhere (53) points toward hepatitis risk factors related to both substance abuse and sexual behavior. However, as various authors indicate, risk is more specifically related to injection drug use, crack cocaine use, and sexual behaviors that are related to male-male contacts or to addiction. Taken together, these findings suggest that preventive interventions should target substance abuse and the use of condoms by men who have sex with other men as well as men and women who abuse substances.

To target substance abuse, integrated treatment of both substance use disorder and severe mental illness is most effective, although still not widely available (30,54,55). Research shows that nearly all clients with dual disorders can be engaged in dual diagnosis treatment when services are integrated and offered in a stagewise fashion and that a majority of these clients will attain stable remission, although treatment and recovery may involve several months or years (30,56). Because substance abuse treatment is likely to reduce drug and sex-related risk behaviors, and thereby prevent the acquisition and spread of infection by those already infected, risk reduction should be a standard component of integrated treatment for patients with dual diagnoses in mental health settings.

Medical care

In a study reported in this issue of the journal, Swartz and colleagues (57) found that persons with both severe mental illness and hepatitis C infection were less likely than those without hepatitis C to receive regular medical care. Study participants who were young, unmarried, black, or male were less likely to have regular sources of medical care. The second critical step in addressing blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness involves improving access to and use of medical care.

People with mental illnesses experience high rates of undetected and untreated medical illnesses (58,59,60) as well as higher rates of medical morbidity and mortality than persons without mental illness (58,61,62). Patient-related barriers to medical care include cognitive and social skills deficits as well as symptoms such as disorganization, avoidance, and paranoia (44,58). Medical providers often consider persons with mental illness to be difficult to treat and poor risks for treatment (63). Inability to pay for care as a result of unemployment, poverty, and lack of insurance further reduces access to medical care (64). The net result is this group receives little or inadequate medical care (63,65).

Provision of adequate medical care for people with severe mental illness requires a linkage between the medical care system and the mental health or dual diagnosis system. Since deinstitutionalization placed the locus of care in the community, mental health clinics have served as the primary contact with the health care system for many clients. A variety of models of integrating medical care and mental health care for this population have been proposed. The initial model was linkage to medical care by mental health case managers, who could serve as translators between the world of modern medicine and the perspective of the person with mental illness (18,65). However, no study has yet demonstrated effective medical care under the brokerage case management model.

A second approach has been to designate psychiatrists in mental health centers as primary medical providers (66,67,68,69,70), but this model has not taken hold. In yet another model, common in England, general medical practitioners provide medical care as well as psychiatric care (71). However, even in this setting clients who are difficult to manage are quickly referred to the specialty psychiatry sector for mental health care, which suggests that this model may be impractical for providing care to persons with dual disorders. Finally, a fourth model, which has demonstrated effectiveness for improving access to care, involves placing a primary medical care provider within the mental health agency (72). In this model, the medical provider becomes part of the mental health team and handles screening, prevention, routine medical care, referral to specialists, and medical follow-up for all nonpsychiatric medical conditions.

Most community mental health systems in the United States use the brokerage case manager model. However, a model that places medical personnel in mental health settings, at least on a periodic basis, may be more efficient. For example, nurses could provide medical education, referral, and counseling about medical problems, including chronic infectious diseases, in the mental health setting. Nurses could also provide direct linkages with infectious disease and hepatology specialists, which would reduce many of the barriers to medical care experienced by clients with mental illness and improve care.

Conclusions

Among the myriad challenges to community mental health care for persons with severe mental illnesses, prevention and treatment of blood-borne infection is emerging as a critical need. To meet this need, the mental health system must stretch its boundaries and competencies in three directions: prevention and treatment measures for blood-borne diseases (screening, testing, immunization, risk reduction, and referral to and support for medical care), more integrated treatment of substance abuse and mental illness, and enhancement of direct linkages with the specialty medical care system. Further research on the effectiveness of these approaches will be developed over the next several years, and their feasibility will be examined in the light of competing service needs.

The authors are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center and Dartmouth Medical School, 105 Pleasant Street, Concord, New Hampshire 03301 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Blood tests and interpretation of their results

1. Aruffo JF, Thompson RG, Gottlieb AA: An AIDS training program for rural mental health providers. Psychiatric Services 46:79-81, 1995Link, Google Scholar

2. Brunette MF, Mercer CC, Carlson CL, et al: HIV-related services for persons with severe mental illness: policy and practice in New Hampshire community mental health. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:347-353, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Coverdale JH, Aruffo JF: AIDS and family planning counseling of psychiatrically ill women in community mental health clinics. Community Mental Health Journal 28:13-20, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fine J, Ioannou C: Working with dually diagnosed patients, in AIDS and People With Severe Mental Illness: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals. Edited by Cournos F, Balakar N. New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, 1996Google Scholar

5. Sullivan G, Koegel P, Kanouse DE, et al: HIV and people with serious mental illness: the public sector's role in reducing HIV risk and improving care. Psychiatric Services 50:648-652, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus infection and HCV related chronic disease. MMWR Recommendation Report 47(RR-19):1-39, 1998Google Scholar

7. Update: recommendations to prevent hepatitis B virus transmission: United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(2):33-34, 1999Google Scholar

8. Moyer LA, Mast EE, Alter MJ: Hepatitis C: I. routine serologic testing and diagnosis. American Family Physician 59:79-92, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

9. Moyer LA, Mast EE, Alter MJ: Hepatitis C: II. prevention counseling and medical evaluation. American Family Physician 59:349-357, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

10. Essock SM, Dowden, S, Constantine, NT, et al: Risk factors for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:836-841, 2003Link, Google Scholar

11. Rosenberg SD, Swanson JW, Wolford GL, et al: The Five-Site Health and Risk study of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:827-835, 2003Link, Google Scholar

12. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31-37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Osher FW, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, et al: Substance abuse and the transmission of hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:842-847, 2003Link, Google Scholar

14. Siegel K, Krauss BJ, Karus D: Reporting recent sexual practices: gay men's disclosure of HIV risk by questionnaire and interview. Archives of Sexual Behavior 23:217-230, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Locke SE, Kowaloff HB, Hoff RG, et al: Computer-based interview for screening blood donors for risk of HIV transmission. JAMA 268:1301-1305, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Duffy JC, Waterton JJ: Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in sample surveys: the effect of computer interviewing in fieldwork. British Journal of Addiction 79:303-308, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lucas RW, Mullin PJ, Luna CB, et al: Psychiatrists and a computer as interrogators of patients with alcohol-related illnesses: a comparison. British Journal of Psychiatry 131:160-167, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Turner JC, Tenhoor WJ: The NIMH community support program: pilot approach to a needed social reform. Schizophrenia Bulletin 4:319-348, 1978Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Czeschinski PA, Binding N, Witting U: Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccinations: immunogenicity of combined vaccine and of simultaneously or separately applied single vaccines. Vaccine 18:1074-1080, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Koff RS: Risks associated with hepatitis A and hepatitis B in patients with hepatitis C. American Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 33:20-26, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lugoboni F, Migliozzi S, Schiesar F, et al: Immunoresponse to hepatitis B vaccination and adherence campaign among injecting drug users. Vaccine 15:1014-1016, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Trubatch BN, Fisher DG, Cagle HH, et al: Vaccination strategies for targeted and difficult to access groups. American Journal of Public Health 90:447, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rosenberg SD, Marsh BJ, Brunette MF, et al: Integrating HIV and Hepatitis Prevention and Intervention With Mental Health Services. Presented at the International AIDS Conference held July 7-12, 2002, in BarcelonaGoogle Scholar

24. Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Johnson BT: Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection: a meta-analytic review of the behavioral outcome literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 18:6-15, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Carey KB: HIV risk reduction for the seriously mentally ill: pilot investigation and call for research. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 28:87-95, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kelly JA, McAuliffe TL, Sikkema KJ, et al: Reduction in risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness who learn to advocate for HIV prevention. Psychiatric Services 48:1283-1288, 1997Link, Google Scholar

27. Susser E, Valencia E, Berkman A, et al: Human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk reduction in homeless men with mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:266-272, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Johnson-Masotti AP, Pinkerton SD, Kelly JA, et al: Cost-effectiveness of an HIV risk reduction intervention for adults with severe mental illness. AIDS Care 12:321-332, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Alverson H, Alverson M, Drake RE: An ethnographic study of the longitudinal course of substance abuse among people with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 36:557-569, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469-476, 2001Link, Google Scholar

31. US Department of Health and Human Services and the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Available at www.hivatis.org/trtgdlns.html. Accessed Nov 19, 2001Google Scholar

32. Davis GL: Treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Clinics in Liver Disease 3:812-826, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy RK, et al: Pegylated (40 kDa) (PEGASYS) interferon alfa-2a in combination with ribavirin: efficacy and safety results from a phase III, randomized, actively controlled multicenter study. Gastroenterology 120:A55, 2001Google Scholar

34. Manns MP, McHutchinson JG, Gordon SC, et al: Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Lancet, 358;958-965, 2001Google Scholar

35. Valentine AD, Meyers CA, Kling MA, et al: Mood and cognitive side effects of interferon-alpha therapy. Seminars in Oncology 25 (1 suppl 1):39-47, 1998Google Scholar

36. US Department of Veterans Affairs: Treatment Recommendations for Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C:2001 version 1.0. Available at www.va.gov/hepatitisc/pved/treatmntgdlnes_00.htm. Accessed Nov 19, 2001Google Scholar

37. Ho SB, Nguyen H, Tetrick LL, et al: Influence of psychiatric diagnosis on interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis C in a veteran population. American Journal of Gastroenterology 96:157-164, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

38. Van Thiel DH, Friedlander L, Molloy PJ, et al: Interferon-alpha can be used successfully in patients with hepatitis C virus-positive chronic hepatitis who have a psychiatric illness. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 7:165-168, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

39. Mulder RT, Ang M, Chapman B, et al: Interferon treatment is not associated with a worsening of psychiatric symptoms in patients with hepatitis C. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 15:300-303, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Hauser P, Soler R, Reed S, et al: Prophylactic treatment of depression induced by interferon-alpha. Psychosomatics 41:439-441, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Dobmeier M, Frick E, Frank S, et al: Schizophrenic psychosis: a contraindication for treatment of hepatitis C with interferon alpha? Pharmacopsychiatry 33:72-74, 2000Google Scholar

42. Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Patients With HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

43. Fillenwater DR, McDaniel JS: Rational psychopharmacology for patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Psychiatric Annals 31:28-34, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Dixon L, Lyles A, Smith C, et al: Use and costs of ambulatory care services among Medicare enrollees with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:786-792, 2001Link, Google Scholar

45. Dixon L, Wohlheiter K, Thompson D: Medical management of persons with schizophrenia, in Comprehensive Care of Schizophrenia: A Textbook of Clinical Management. Edited by Lieberman JA, Murray RM. London, United Kingdom, Martin Dunitz, 2001Google Scholar

46. Fisher EP, Owen RR, Cuffel BJ: Substance abuse, community service use, and symptom severity of urban and rural residents with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:980-984, 1996Link, Google Scholar

47. Drake RE, Brunette MF: Complications of severe mental illness related to alcohol and drug use disorders, in Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 14: The consequences of Alcoholism. Edited by Galanter M. New York, Plenum, 1998Google Scholar

48. Walkup J, Sambamoorthi U, Crystal S: Incidence and consistency of antiretroviral use among HIV-Infected Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:174-178, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Gordon FD: Cost-effectiveness of screening patients for hepatitis C. American Journal of Medicine 107:36S-40S, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Mast EE, Williams IT, Alter MJ, et al: Hepatitis B vaccination of adolescent and adult high-risk groups in the United States. Vaccine 16:S27-S29, 1998Google Scholar

51. Wong JB: Interferon treatment for chronic hepatitis B or C infection: costs and effectiveness. Acta Gastroenterologica Belgica 61:238-242, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

52. Wong JB: Cost-effectiveness of 24 or 48 weeks of interferon alpha-2b alone or with ribavirin as initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy group. American Journal of Gastroenterology 95:1524-1530, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

53. Rosenberg SD, Trumbetta SL, Mueser KT, et al: Determinants of risk behavior for HIV/AIDS in people with severe mental illness. Comprehensive Psychiatry 42:263-271, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Carey KB: Substance use reduction in the context of outpatient psychiatric treatment: a collaborative, motivational, harm reduction approach. Community Mental Health Journal 32:291-306, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Noordsy DL: Integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for severe psychiatric disorders. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 4:129-139, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

56. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Mueser KT, et al: Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:589-608, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ, et al: Regular sources of medical care among persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection. Psychiatric Services 54:854-859, 2003Link, Google Scholar

58. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B: Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:212-217, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Koran LM, Sox HC Jr, Marton KI, et al: Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients: I. results in a state mental health system. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:733-740, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Koranyi EK: Morbidity and rate of undiagnosed physical illness in a psychiatric clinic population. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:414-419, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Dalmau A, Bergman B, Brismar B: Somatic morbidity in schizophrenia: a case control study. Public Health 111:393-397, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Simpson JC, Tsuang MT: Mortality among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:485-499, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al: Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:565-572, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Aro S, Aro H, Keskimaki I: Socio-economic mobility among patients with schizophrenia or major affective disorder: a 17 year retrospective follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:759-767, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Mental disorders and access to medical care in the US. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1775-1777, 1998Link, Google Scholar

66. Schwab B, Drake RE, Burghardt EM: Health care of the chronically mentally ill: the culture broker model. Community Mental Health Journal 24:174-184, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Oken D, Fink PJ: General psychiatry: a primary-care specialty. JAMA 235:1973-1974, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Fink PJ, Oken D: The role of psychiatry as a primary care specialty. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:998-1003, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Shore JH: Psychiatry at a crossroad: our role in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1398-1403, 1996Link, Google Scholar

70. Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, Bray JD, et al: Medical services in community mental health programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:1045-1047, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

71. Mechanic D: Integrating mental health into a general health care system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:893-897, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

72. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al: Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:861-868, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar