Integrating Outcomes Research Into Clinical Practice

Abstract

A cohort of 102 psychiatric outpatients with major depressive disorder were followed up for about two years. Prospective ratings were obtained at each medication management visit with two instruments that measured changes in symptoms. The mean time to recovery was very similar to that reported in the National Institute of Mental Health's Collaborative Depression Study. This finding supports the validity of using brief instruments to measure outcomes in routine clinical practice.

Recognition of the need to conduct outcomes research in the real world has grown in recent years (1). However, little research of this sort has actually occurred, partly because the demands of clinical practice already stretch the limits of what clinicians can accomplish during routine follow-up visits.

In this report we describe a process we have started using in which brief outcome ratings are incorporated into outpatient practice. We have used these ratings to compare the effectiveness of augmenting and switching antidepressants among patients who have not responded to an initial adequate trial (2), to evaluate the outcomes of depressed patients whose antidepressants were switched because of intolerable side effects during remission (3), and to assess the short-term spontaneous remission rate of patients with depression who did not receive somatic therapy (4).

Here we describe in more detail the process through which we have incorporated outcome ratings into our practice and illustrate how these ratings can be used to depict the natural course of a disorder. We discuss the validity of our findings by comparing our results with those obtained in the more methodologically rigorous National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study.

Methods

All patients were treated by the second author between 1996 and 1999 at Rhode Island Hospital's outpatient psychiatric department, a tertiary care academic center affiliated with Brown University. All 102 patients in the study received a principal diagnosis of unipolar major depressive disorder at baseline. For 83 patients, the diagnosis was made by a trained diagnostic interviewer using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) (5) as part of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project; for 19 patients, the diagnosis was made by the treating clinician.

The mean±SD age of the patients was 40.5±12.8 years; 56 patients (55 percent) were female, 95 (93 percent) were white, 58 (57 percent) were married or cohabiting, and 65 (64 percent) had at least some college or university education. The median duration of the depressive episode at intake was 34 weeks, and the mean score on the Global Assessment of Functioning was 52.3±7.1. (Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.) The Rhode Island Hospital's institutional review board approved the research protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent. All patients received open-label treatment with standard antidepressant medications. Antidepressants were selected on a case-by-case basis according to standard clinical practice.

Ratings from the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating (SCOR) were prospectively obtained by the treating clinician at each follow-up visit. SCOR ratings are analogous to the ratings used in the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE), the instrument used in the Collaborative Depression Study (6). The SCOR was chosen because we wanted to obtain outcome ratings for all psychiatric disorders, not just mood disorders. The SCOR is a 6-point rating scale on which a rating of 5 or 6 represents threshold disorders, a rating of 3 or 4 represents subthreshold disorders, and a rating of 1 or 2 indicates that no or minimal symptoms of the disorder are present. For this study, we defined recovery as at least two consecutive SCOR ratings of 1 or 2 occurring over a period of at least eight weeks.

In addition to establishing the time to recovery, we were interested in establishing the time to improvement. Thus we prospectively obtained Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI) ratings at each follow-up visit (7). In most antidepressant efficacy studies, a CGI rating of 1, indicating very much improved, or 2, indicating much improved, is generally considered a positive outcome. Improvement was defined as achievement of at least two consecutive CGI ratings of 1 or 2 separated by at least eight weeks. All ratings were recorded in the progress notes of each patient's chart and were collected and analyzed after a systematic chart review by the first author.

Patients who terminated treatment were not followed up. A total of 55 patients (54 percent) terminated treatment within two years of their initial evaluation. For these patients, we used the SCOR and CGI ratings obtained at the final visit. If the final SCOR or CGI rating was 1 or 2, we considered the patient to have recovered (SCOR rating) or improved (CGI rating), even if the full eight weeks of recovery or improvement had not yet been documented. When these criteria were used, six patients who dropped out of treatment were considered to have recovered, and six were considered to have improved.

To estimate the cumulative probability of the continuation of depression during treatment, we used the Kaplan-Meier method (8). We performed separate analyses of the SCOR and CGI ratings, censoring patients at the time they terminated treatment or at the end of the follow-up period.

Results

The cumulative probabilities of sustained improvement on the basis of CGI ratings were as follows: 55 percent of the patients were much or very much improved within eight weeks, 67 percent within 13 weeks, 85 percent within 26 weeks, 92 percent within one year, and 95 percent within two years. The median time to sustained improvement was 6.5 weeks.

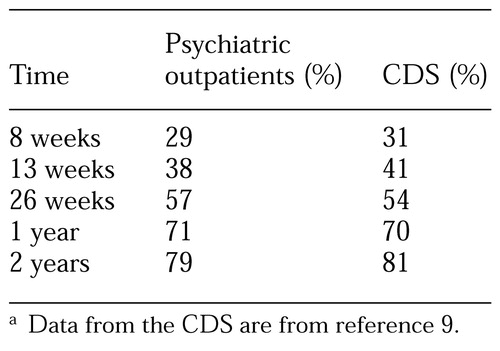

The cumulative probabilities of recovery based on the SCOR ratings for each patient are listed in Table 1. Twenty-nine percent of the patients had recovered from their depressive episode within eight weeks, 38 percent within 13 weeks, 57 percent within 26 weeks, 71 percent within one year, and 79 percent within two years. The median time to recovery was 19 weeks. Seventeen patients remained in treatment at week 52 without having achieved a remission of symptoms. The cumulative probability of recovery in this cohort during the second year of treatment was 27 percent—less than half of what was found during the first year of treatment.

Table 1 also lists recovery rates among patients in the Collaborative Depression Study (9). Despite enormous differences in the methods and scopes of these two studies, the results are strikingly similar. The median time to recovery in our sample—19 weeks—is nearly identical to that reported by Solomon and colleagues (10) when they examined the duration of recurrent depressive episodes among patients from the Collaborative Depression Study.

Discussion and conclusions

In this report we sought to demonstrate that brief but meaningful standardized outcome ratings can be incorporated into routine clinical practice. The CGI and SCOR ratings together take only a few minutes to obtain. These ratings have several potential uses. From a clinical standpoint, the question often arises as to how much improvement has been achieved during an antidepressant trial or after a switch in antidepressants. A quick review of CGI and SCOR ratings can provide a brief but objective measure of improvement or deterioration in symptoms over a long period. From a research standpoint, such ratings can be used to evaluate important clinical questions that are relevant to practicing clinicians (2,3,4).

The results of our study are, of course, limited in that they are restricted to the practice of a single clinician. It remains to be seen whether nonacademic clinicians can be induced to include such ratings in their follow-up visits. If so, a wealth of information would become available to address many important clinical questions.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and human behavior at the Brown University School of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, 235 Plain Street, Suite 501, Providence, Rhode Island 02905 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Recovery rates of 102 psychiatric outpatients with unipolar major depression and rates for 431 patients reported in the Collaborative Depression Study (CDS)a

a Data from the CDS are from reference 9

1. Wells KB: Treatment research at the crossroads: the scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:5-10, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Posternak MA, Zimmerman M: Switching versus augmentation: a prospective, naturalistic comparison in depressed, treatment-resistant patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:135-142, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Posternak MA, Zimmerman M: The effectiveness of switching antidepressants during remission: a case series of depressed patients who experienced intolerable side effects. Journal of Affective Disorders, in pressGoogle Scholar

4. Posternak MA, Zimmerman M: Short-term spontaneous improvement rates in depressed outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 62:799-804, 2001Google Scholar

5. First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997Google Scholar

6. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al: The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:540-548, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Guy W: ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, in US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication ADM 76-338, vol 23. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

8. Kalbleish JD, Prentice RL: The Statistical Analysis of Failure-Time Data. New York, Wiley, 1980Google Scholar

9. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, et al: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:809-816, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al: Recovery from major depression: a 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1001-1006, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar