Delays in Adopting Evidence-Based Dosages of Conventional Antipsychotics

Abstract

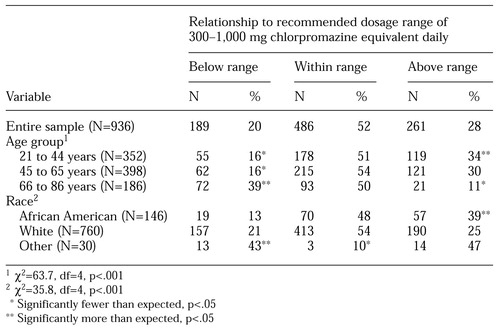

By the 1980s, strong research evidence had emerged supporting the use of moderate doses of conventional antipsychotics—between 300 and 1,000 mg of chlorpromazine equivalent daily. We conducted a cross-sectional study of dosages of antipsychotics prescribed for 936 veterans with schizophrenia in 14 facilities between 1991 and 1995. Only 52 percent of these patients received prescriptions for recommended dosages; dosages were below the recommended range for 20 percent and above the range for 28 percent. African Americans were more likely than others to have received high dosages. These data suggest that there was considerable delay in the adoption of evidence-based dosing of conventional antipsychotics. Efforts must be made to transfer research findings more rapidly into practice.

Schizophrenia is a devastating and costly illness that affects 1.1 percent of the population. Many changes in standard treatments for schizophrenia have occurred during the past two decades, only some of which have been based on strong research evidence. Beginning in the 1970s, randomized controlled trials showed that daily doses between 300 and 1,000 mg of chlorpromazine equivalent were optimal for controlling psychotic symptoms (1). Doses below 300 mg were less effective, and doses above 1,000 mg were no more effective than moderate doses but caused more side effects. In 1988 a review of 19 randomized controlled trials strongly endorsed moderate dosages of antipsychotic agents (1). A year later, a standard textbook also endorsed moderate dosages (2). These reports followed a decade during which high dosages of antipsychotics and "rapid neuroleptization" had been the standard of practice, despite the existence of only weak supporting evidence (3).

However, the dissemination of evidence-based dosage recommendations may have been difficult. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) reported that between 1994 and 1996, clinicians in two states frequently prescribed antipsychotics at dosages outside of recommended ranges (4).

We examined the dosages of conventional antipsychotics that were prescribed for a large national cohort of veterans with schizophrenia who were treated between 1991 and 1995 in 14 facilities in 14 different states. Our data indicate the extent to which clinicians had adopted moderate dosages of antipsychotics some ten to 15 years after research reports and three to eight years after review articles and texts had supported their use.

Methods

Of 1,637 veterans who were enrolled in a study comparing enhanced psychosocial programming with standard care, 1,307 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The study was conducted between January 9, 1991, and December 19, 1995, at 14 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities. Inpatients and outpatients were eligible for enrollment if they had been hospitalized for at least 150 days or had had five or more admissions during the previous 12 months (5). We conducted a secondary analysis of data collected at baseline from the 936 patients who were receiving oral conventional agents.

The patients' ages and races were obtained from national VA databases. Data on the patients' medications, dosages, and ratings of symptoms were obtained from clinician assessment forms that were completed at the time of enrollment. Clinicians rated the patients' symptoms by using the 19-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Each BPRS item was rated on a scale of 0 (not present) to 6 (extremely severe) (6).

Videotapes of patient interviews were used to train the clinicians in the use of the BPRS. The clinicians compared their ratings with those of other team members and the expert rater who conducted the videotaped interview. Interrater reliability testing was conducted. In all analyses, dosages of antipsychotics were expressed in chlorpromazine equivalents (7).

Simple descriptive statistics were computed. Chi square analyses were used to examine the relationship between categorical patient characteristics and whether patients received dosages below, within, or above the recommended range. Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables in three or more groups. The Mantel-Haenszel chi square test was used to identify any significant linear trend in the proportion of patients who received recommended dosages, by year of enrollment.

Results

The mean±SD age of the 936 patients was 51.7±12.8 years. Most of the patients (906, or 96.8 percent) were male. Most patients (760, or 81.2 percent) were white; 146 (15.6 percent) were African American, and 30 (3.2 percent) were of other races. The patients' mean±SD BPRS score at enrollment was 21.7±12.8.

The mean±SD daily dose of antipsychotics was 932.3±921 mg chlorpromazine equivalent; 189 patients (20 percent) were receiving doses below the recommended range, 486 (52 percent) were receiving doses within the recommended range, and 261 (28 percent) were receiving doses above the recommended range.

Age group and race were significantly associated with whether the prescribed dose was below, within, or above the recommended range, but sex was not. As can be seen in Table 1, younger patients and African-American patients were more likely to have received prescriptions for high dosages; 39 percent of African-American patients but only 25 percent of white patients received a daily dose of more than 1,000 mg of chlorpromazine equivalent.

We observed a significant relationship between treatment facility and prescribed dosage category (χ2= 89.01, df=26, p<.001). The proportion of patients whose dosages were within the recommended range at the various sites varied between 39 percent and 65 percent. No significant increase was observed in the use of recommended dosages over time (1991 to 1995).

In all dosage categories, a significant proportion of patients continued to experience severe symptoms; 31 (16 percent) of the 189 patients who received low dosages, 106 (22 percent) of the 486 who received recommended dosages, and 96 (37 percent) of the 261 who received high dosages had BPRS scores above 30.

Discussion

Our findings, consistent with those of the PORT study, showed that only half of the patients in a large cohort were treated with dosages of conventional antipsychotics that were supported by the literature; significant proportions received dosages below or above the recommended range. The geographically diverse sites varied significantly in the use of moderate dosages. Such variation suggests that factors other than research findings were driving practice patterns (8). Deviations from evidence-based dosing persisted throughout the study period, despite the continued publication of the results of randomized controlled trials and review articles that supported moderate dosages.

In our sample, younger patients and African Americans were more likely than others to have received prescriptions for high dosages. Younger patients may have been more likely to receive high dosages because they are better able to tolerate them. However, African Americans are no more likely to tolerate and no more likely to require high doses than whites (9). The PORT investigators have also reported that African Americans received higher dosages of antipsychotics (7).

Because ours was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to determine whether patients had had previous trials of antipsychotics with dosages within recommended ranges. Also, we were unable to determine the clinicians' reasons for deviating from recommended dosages.

The clinicians in our study may have used suboptimal dosages because their patients had unacceptable adverse effects or refused higher dosages. Although additional benefit would have been unlikely, the clinicians may have prescribed high dosages to patients who did not respond to conventional agents because they believed that they had few alternatives. Administrative barriers may have prevented easy access to atypical agents, and limited time or resources may have prevented the clinicians from pursuing other treatment options. It is likely that a few patients responded to high dosages after failing to respond to lower dosages and that high dosages were sometimes used to treat other symptoms, such as hostility, in addition to psychosis.

Our data reflect prescribing practices from 1991 to 1995. Since 1995, guidelines have codified dosages of antipsychotics, additional atypical agents have been introduced, and barriers to the use of atypical antipsychotics have decreased. Dosing practices in the use of antipsychotics likely have changed and will continue to change. However, we believe that data on deviations from evidence-based dosages remain germane for two reasons.

First, conventional antipsychotics are likely to persist in the armamentarium of many mental health organizations because of concerns about costs and a growing realization that the newer drugs may be no more efficacious than conventional antipsychotics (10). Second, these data sound a general cautionary note about delays in translating research findings about the treatment of schizophrenia into practice. Our data show that 15 years after research reports and eight years after review articles supported moderate dosages, a troubling proportion of patients were treated with high dosages—a practice for which there is little supporting evidence.

Patients who have schizophrenia may continue to be at risk of receiving treatments for which there is little evidence. Evidence-based treatments for schizophrenia are few, many treatments are only partially effective, and patients often have dramatic and disabling symptoms. Clinicians who are faced with symptomatic patients may be quick to move on to the next promising treatment or reluctant to abandon unproven treatments. Regular monitoring of the pharmacologic treatment of patients who have schizophrenia may be important in optimizing the care of these individuals.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Mental Health Strategic Health Group of the Veterans Health Administration Headquarters and Research Career Development Award RC-98350-1 from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Valenstein, Ms. Copeland, Dr. Blow, and Ms. Visnic are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Evaluation, and Research Center (SMITREC) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Dr. Valenstein and Dr. Blow are also affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Dr. Owen is with the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research in Little Rock, Arkansas, and with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Arkansas in Little Rock. Send correspondence to Dr. Valenstein at the Health Services Research and Development Field Office, SMITREC, P.O. Box 130170, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48113-0170 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Distribution of prescribed dosages of antipsychotics relative to the recommended range among 936 veterans with schizophrenia, by age group and race

1. Baldessarini RJ, Cohen BM, Teicher MH: Significance of neuroleptic dose and plasma level in the pharmacological treatment of psychoses. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:79-91, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Davis JM, Barter JT, Kane JM: Antipsychotic drugs, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 5th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989Google Scholar

3. Reardon GT, Rifkin A, Schwartz A, et al: Changing patterns of neuroleptic dosage over a decade. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:726-729, 1989Link, Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Blow FC, Ullman E, Barry KL, et al: Effectiveness of specialized treatment programs for veterans with serious and persistent mental illness: a three-year follow-up. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:389-400, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Overall JE: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:97-99, 1988Google Scholar

7. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-32, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wennberg DE: Variation in the delivery of health care: the stakes are high. Annals of Internal Medicine 128:866-868, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ruiz P, Varner RV, Small DR, et al: Ethnic differences in the neuroleptic treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:163-172, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. British Medical Journal 321:1371-1376, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar