Psychiatric Disorders in Preschool Offspring of Parents With Bipolar Disorder: The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS)

Abstract

Objective

The authors evaluated lifetime prevalence and specificity of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders and severity of depressive and manic symptoms at intake in preschool offspring of parents with bipolar I and II disorders.

Method

A total of 121 offspring ages 2–5 years from 83 parents with bipolar disorder and 102 offspring of 65 demographically matched comparison parents (29 with non-bipolar psychiatric disorders and 36 without any lifetime psychopathology) were recruited for the study. Parents with bipolar disorder were recruited through advertisements and adult outpatient clinics, and comparison parents were ascertained at random from the community. Participants were evaluated with standardized instruments. All staff were blind to parental diagnoses.

Results

After adjustment for within-family correlations and both biological parents' non-bipolar psychopathology, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, particularly those older than age 4, showed an eightfold greater lifetime prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and significantly higher rates of having two or more psychiatric disorders compared to the offspring of the comparison parents. While only three offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had mood disorders, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, especially those with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, had significantly more severe current manic and depressive symptoms than comparison offspring.

Conclusions

Preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder have an elevated risk for ADHD and have greater levels of subthreshold manic and depressive symptoms than children of comparison parents. Longitudinal follow-up is warranted to evaluate whether these children are at high risk for developing mood and other psychiatric disorders.

The study of the early manifestations of bipolar disorder in youths, particularly during early childhood, is of prime importance because of the severe impact that this condition has on the normal psychosocial development of children, on their families, and on society in general (1–3).

The single largest risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder is a positive family history of the disorder (3). Therefore, one way to try to identify the prodromal and earliest clinical manifestations of bipolar disorder is to study the offspring of adults with the disorder. This information is critical for developing early interventions that may prevent the onset of pediatric bipolar disorder and promote the normal psychosocial development of the child (3, 4).

Risk studies of pediatric bipolar disorder have shown that offspring ages 6 to 18 years of parents with bipolar disorder have an elevated risk of developing early-onset bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders (3, 5–11). The largest of these studies is the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) (5). The BIOS showed that school-age offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had significantly higher rates of any axis I disorder, bipolar spectrum disorders (mostly not otherwise specified), major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than offspring of community comparison parents. However, after adjustment for both biological parents' non-bipolar psychopathology, the differences in the rates of major depressive disorder, disruptive behavior disorders, and ADHD were no longer significant.

The above-noted studies were conducted with offspring age 6 and older. However, parents with either a personal or a family history of bipolar disorder often wonder whether their preschool child's behavioral and emotional problems are due to a bipolar diathesis, since some of these problems are reminiscent of their own or their relatives' problems during childhood. The few studies of preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder suggest that relative to offspring of comparison parents (mostly healthy), these children have higher rates of observed behavioral disinhibition, disruptive and depressive symptoms, fidgetiness, hyperactivity, disproportionate levels of aggression, and difficulty managing anger and hostile impulses during observed interactions with peers and unknown adults (12–16). Some of these problems (disruptive and depressive symptoms) were found to persist and even increase (e.g., depression) over time (14). However, further research is needed to confirm these findings since these studies used very small samples of children and parents with bipolar disorder and had other methodological limitations, as delineated elsewhere (5, 7).

Epidemiological and clinical studies have shown that clinically relevant symptoms and psychiatric disorders are reliably diagnosed in preschool children as young as 2 years old (17–20). Symptoms of major depressive disorder are also reliably ascertained in this population and are associated with significant psychosocial impairment and high rates of mood disorders in family members (18, 19, 21, 22). Although several case reports (23–27) and a recent study (24) showed that preschoolers can be diagnosed with DSM-IV bipolar disorder, the diagnosis of mania in young children remains controversial, and further longitudinal research is warranted.

Our primary goal in this study was to evaluate whether preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had significantly more lifetime DSM-IV axis I disorders than a demographically matched sample of preschool offspring of community parents (with and without non-bipolar psychopathology). In addition to categorical diagnoses, since subthreshold mood symptoms may precede the onset of full-blown mood disorders, the presence and severity of mood symptoms at intake were explored. Based on the available literature, we hypothesized that offspring of parents with bipolar disorder would have higher rates of ADHD, disruptive behavior disorders, and anxiety and mood disorders and higher ratings on depressive and manic symptom scales relative to offspring of comparison parents.

Method

Participants

Parents (probands)

As part of BIOS, parents with DSM-IV bipolar I or bipolar II disorder who had preschool children were recruited through advertisements (60%), adult bipolar studies (9%), and adult outpatient clinics (31%). There were no differences between recruitment sources in bipolar subtype, age at onset of bipolar disorder (17.35 years [SD=6.2]), or rates of non-bipolar disorders. Exclusion criteria included current or lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia, mental retardation, and mood disorders secondary to substance abuse, medical conditions, or medications.

Comparison parents, group-matched by age, sex, and neighborhood (based on the postal codes and area codes and the first three digits of telephone numbers of the parents with bipolar disorder), were recruited from the community via telephone using random dialing by the University Center for Social and Urban Research of the University of Pittsburgh. The exclusion criteria for the comparison parents were the same as those for the parents with bipolar disorder, with the additional requirements that neither of the biological parents could have bipolar disorder and they could not have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder. However, they could have other psychiatric disorders or be healthy.

Offspring of bipolar and comparison parents

Except for children with a condition that impeded their participation in the study (e.g., mental retardation), all offspring ages 2–5 from each family were included.

Procedures

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all parents.

For all parents who participated as probands and 46% (68/148) of the biological co-parents, psychiatric disorders were ascertained face-to-face using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Lifetime ADHD, disruptive behavior disorders, and separation anxiety disorder were ascertained using the respective items from DSM-IV. The SCID kappa values were ≥0.8.

The Family History–Research Diagnostic Criteria method (28) (plus ADHD, separation anxiety disorder, and disruptive behavior disorder items from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version [K-SADS-PL]) (29) was used to ascertain psychiatric history from biological co-parents who were not seen in face-to-face interviews, as well as for siblings and second-degree relatives.

Parents were interviewed about their children for the presence of lifetime psychiatric disorders using the K-SADS-PL. In addition, the severity of the worst past and current (a month preceding the interview) manic or hypomanic and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (30, 31) and the depression section of K-SADS–Present Episode Version (32) (for these instruments, see www.wpic.pitt.edu/research under "Assessment Instruments"). Individual symptom items are rated on 5- or 6-point Likert scales (ranging from "not present" to "severe" or "extreme"). The sums of 13 manic symptom items on the Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (range=0–64; for the scoring instructions, see reference 30), the five manic items that do not overlap with ADHD symptoms and that were shown to separate preschool children with bipolar disorder from children with and without non-bipolar psychopathology (range=0–25) (24), and 12 depression items from the K-SADS depression section that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms of major depressive disorder (range=0–60) (32) were analyzed. Pervasive developmental disorders were ascertained using a DSM-IV symptom checklist (Cronbach alpha=0.9).

The K-SADS-PL has adequate psychometric properties for evaluating psychiatric disorders in preschool children (8, 33–35). Details regarding the procedures to use the K-SADS-PL in preschoolers and its psychometric properties and limitations as compared with other instruments for preschool children have been described in detail elsewhere (35). Briefly, the K-SADS-PL was administered by experienced bachelor's- or master's-level interviewers who were instructed on how to ask parents developmentally appropriate questions regarding their children's psychopathology. For example, a normal child is expected to be elated in certain situations and express exaggerated concepts about his or her abilities, which should not be misinterpreted as pathological elation or grandiose ideations (24). Mood symptoms that are common in other psychiatric disorders (e.g., irritability, agitation) were not rated as present in the mood sections unless they intensified with the onset of abnormal mood. Comorbid diagnoses were not assigned if they occurred exclusively during a mood episode. Results of the interview were always presented to child psychiatrists, who were ultimately responsible for all diagnoses. Only children with clinically relevant and persistent symptoms that affected their psychosocial functioning were diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder.

All diagnoses were made using DSM-IV criteria. However, operationalized criteria for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified were used (36). In children and adolescents with this subtype of bipolar disorder, the clinical picture, comorbid disorders, family history, and longitudinal outcome have been shown to be similar to but less severe than in youths with bipolar I disorder (36). Moreover, approximately 40% of youths with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, especially those with a family history of bipolar disorder, converted to bipolar I or II disorder (37). With the exception of bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and pervasive developmental disorders in children and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified in biological co-parents, no other not-otherwise-specified disorders were included in this analysis. As described in further detail elsewhere, kappa values for all disorders ranged from 0.80 to 0.90 (35).

Caregiver-Teacher Report Forms (38) were requested from all caregivers of children who were attending day care or preschool programs.

Approximately 75% of the assessments were carried out in the participants' homes. To ensure blindness to parental diagnoses, different interviewers assessed the parents' and children's psychopathology, and the child psychiatrists were blind to parental diagnoses. Interviewers were asked to complete a "guess form" reporting whether they thought the parents were in the bipolar disorder group or the comparison group. They guessed correctly in 74% of the cases. Of those who guessed correctly, 59% were "not at all certain" and 33% were "somewhat certain" about their guess. In addition, in 8% of the cases they were "definitely certain" or the blind was broken by the parent. The psychiatrists remained blind to parental status in all cases. All parents', children's, and relatives' diagnoses were made according to the best-estimate procedure (39). Socioeconomic status was ascertained using the Hollingshead scale (40).

Statistical Analyses

The differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between the groups were evaluated by t test, chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Since both biological parents' non-bipolar psychopathology may affect the risk for psychiatric disorders in their offspring and more than one child from each family was included ("within-family correlations"), the effects of these variables were analyzed using mixed logistic and mixed-effects nominal logistic regressions, respectively.

Effect sizes for continuous and categorical variables were calculated as described by Cohen (41). All p values are based on two-tailed tests.

Results

Parents

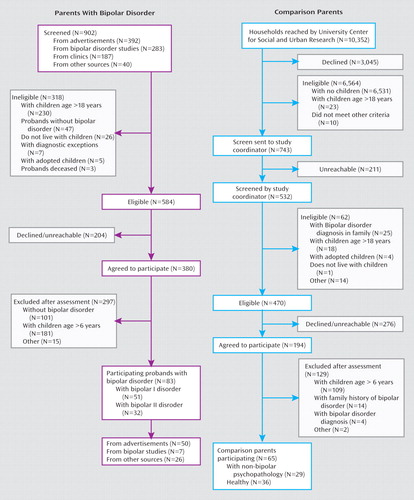

The recruitment flow of parents with bipolar disorder and comparison parents has been described in detail elsewhere (5) and is summarized in Figure 1. Since the initial screening was done over the telephone and before participants' consent was obtained, the institutional review board did not permit the recording of demographic information. Thus, comparisons between screened individuals who declined to participate and those who agreed to participate further are not available.

Eighty-three parents (67 of them [80.7%] female) with bipolar disorder (51 with bipolar I disorder and 32 with bipolar II disorder) and 65 community comparison parents (29 with non-bipolar psychiatric disorders and 36 without any psychopathology) who had offspring 2–5 years old were recruited to the study. In only two families did both parents have bipolar disorder. About 80% of parents with bipolar disorder reported that their initial DSM mood episode started when they were ≤22 years old and 30% before they were 13 years old.

The comparison parents had no first- or second-degree family history of bipolar disorder.

Demographic comparisons

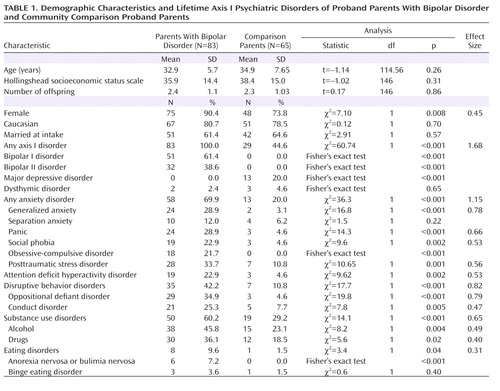

Except for a greater likelihood of being female among parents with bipolar disorder than among comparison parents, there were no between-group differences in demographic characteristics (Table 1). On average, both groups of parents included two children in the study.

|

Axis I disorders in probands

With the exception of similar prevalences of separation anxiety disorder, dysthymic disorder, and binge eating disorder, all other psychiatric disorders were present at higher rates in the parents with bipolar disorder than in the comparison parents (p values, ≤0.04; effect sizes, 0.31–1.68). Within the bipolar parent group, there were no significant differences in the rates of psychopathology between those recruited through advertisement and those recruited by other means.

Axis I disorders in the biological co-parents

There was no significant difference between parents with bipolar disorder and comparison parents in the proportion of direct assessments used to ascertain the nonproband biological parent's psychiatric disorders (56% and 44%, respectively). The biological co-parents of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had higher rates of any axis I disorder than the biological co-parents of offspring of comparison parents (40.9% compared with 24.7%, p=0.02). They also had higher rates of bipolar disorder (3.2% compared with 0%), substance abuse (26% compared with 16%), and disruptive behavior disorders (3.2% compared with 1.2%), but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Offspring

Demographic comparisons

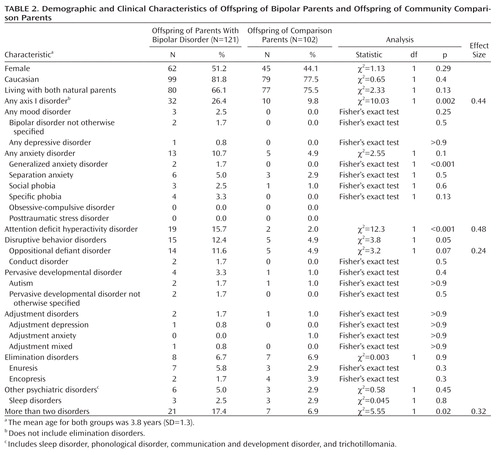

A total of 121 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and 102 offspring of comparison parents (58 from parents with at least one parent with non-bipolar psychopathology and 44 from healthy parents) were recruited. There were no between-group differences in demographic characteristics (Table 2). As expected, the mother was the reporter for most (78.9%) children. At intake, five children of the parents with bipolar disorder were taking psychotropic medications, mainly stimulants. None of the children of the comparison parents were taking medications.

|

Axis I disorders

As shown in Table 2, relative to the offspring of comparison parents, the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder showed significantly greater lifetime prevalence of any axis I disorder, disruptive behavior disorders, ADHD, and two or more disorders (p values, ≤0.05; effect sizes, 0.24–0.48); they also had a higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Two offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (they did not meet the DSM-IV duration criteria for bipolar disorder), one had depressive disorder not otherwise specified, and one had adjustment disorder with depressed mood. The offspring of comparison parents did not have mood disorders.

Except for oppositional defiant disorder, which was diagnosed equally in children younger and older than age 4, about 80% of disorders occurred in children older than age 4.

There were no differences in rates of psychiatric disorders between offspring of parents with bipolar I disorder and offspring of parents with bipolar II disorder. Parental age at onset of mood disorder was not significantly associated with offsprings' rate of having any axis I disorder. Among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, having any axis I disorder was not significantly associated with the mothers' lifetime bipolar diagnosis or any active axis I disorder at the time of assessment.

There were no differences in rates of psychiatric disorders between offspring of parents whom the interviewers correctly guessed had bipolar disorder and those of parents whom the interviewers incorrectly guessed had bipolar disorder. The same results were observed among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder.

Mixed-effects logistic regressions

Adjusting for both biological parents' non-bipolar psychopathology and within-family correlations showed that relative to offspring of comparison parents, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had a significantly higher risk for ADHD (odds ratio=8.17, 95% CI=1.3–52.6) and for having two or more disorders (odds ratio=6.4, 95% CI=1.1–40). Comparisons for disruptive behavior disorders and any axis I disorder were not significant.

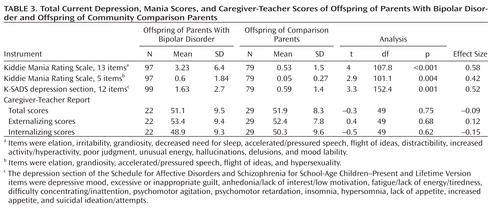

Severity of manic and depressive symptoms

As depicted in Table 3, scores for the Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (5 and 13 items) and the 12-item K-SADS depression section were significantly higher in offspring of the parents with bipolar disorder relative to those of offspring of comparison parents. Adjusting for age, sex, parental diagnoses, and child's oppositional defiant disorder and ADHD did not change the results. However, there were significant interactions, with offspring with ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder and a parent with bipolar disorder showing higher scores on the Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (5 and 13 items) and K-SADS depression section (p values, <0.04; effect sizes, 0.3–0.5).

|

Children with high scores on the Kiddie Mania Rating Scale (5 and 13 items) had high scores in the 12-item K-SADS depression section (r=0.46, p<0.001, and r=0.62, p<0.001, respectively).

Exploratory analyses showed that with the exception of grandiosity and psychotic symptoms, all other manic symptoms (for a list of all manic symptoms, see the footnotes in Table 3) were significantly higher in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (p values, ≤0.04; effect sizes, 0.35–0.63). After Bonferroni corrections were made, elation, irritability/anger, unusual energy, and mood lability remained statistically significant. For the depressive symptoms, between-group differences were due mainly to the severity of irritability, difficulty concentrating, inattention, slow thinking, psychomotor agitation, and insomnia (p values, ≤0.05; effect sizes, 0.26–0.36). After Bonferroni corrections were made, these differences became nonsignificant. About 96% of the severity scores of individual manic and depressive symptoms were classified as mild or less.

Caregiver-Teacher Report Forms

Caregiver-Teacher Report Forms were available for 56 (53.3%) of the 105 preschoolers who attended day care. Five reports were incomplete, leaving a total of 51 caregiver reports (22 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and 29 offspring of comparison parents). There were no demographic or clinical differences between the children whose caregivers completed the Caregiver-Teacher Report Forms and those whose caregivers did not.

Pearson correlations for the total, internalizing, and externalizing scores of the parent's Child Behavior Checklist (35, 38) and caregiver scores ranged from 0.31 to 0.38 (p values, ≤0.02).

There were no differences in the total, internalizing, and externalizing caregiver scores between offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and offspring of comparison parents. However, only five offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and three offspring of comparison parents who had caregiver reports had ADHD and/or oppositional defiant disorder. Combining the children with ADHD and/or oppositional defiant disorder (N=8) showed that they had significantly higher caregiver scores on the attention subscale when compared with those without these disorders (p=0.01).

Discussion

Relative to preschool offspring of comparison parents and after adjustment for both biological parents' non-bipolar disorders and within-family correlations, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had an eightfold greater rate of ADHD and significantly higher rates of having two or more psychiatric disorders. There were no differences in the rates of psychiatric disorders between offspring of parents with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. While only three offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had mood disorders, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, especially offspring with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, had significantly more severe current manic and depressive symptoms than offspring of comparison parents. In a subset of children, caregivers or teachers reported significantly more psychopathology in children with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder than in those without these disorders.

Before we discuss these findings, the limitations of this study deserve comment. First, as in any pediatric study, and especially with preschoolers, the main informants for both the bipolar and comparison parent groups were the mothers. Moreover, in about half of the cases, the psychopathology in the biological co-parents was ascertained by interviewing the main informant. However, there were no differences between the bipolar and comparison parent groups in the rate of mothers serving as main informants and in the proportion of direct and indirect interviews of biological co-parents. Second, the children's psychopathology was ascertained through parents, and parental psychiatric illnesses could have inflated the rates of reported psychopathology in offspring. However, although the literature regarding this issue is controversial, it appears that if there is any effect, it is small (42–44). Similar biases existed for both parent groups because about 50% of the comparison parents had axis I disorders, and rates of psychiatric disorders in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder were not associated with their mothers' lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder and acute mood symptoms at intake. In contrast to the above arguments, there were no differences in caregiver scores between offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and offspring of comparison parents. Nevertheless, only a few offspring who had caregiver reports had ADHD and/or oppositional defiant disorder, and the rest of the sample was healthy. To help clarify these issues, more confirmatory work is needed using parent reports in tandem with measures less likely to be influenced by bias (direct observation measurements in particular). Third, the nature of the study could have attracted parents with more severe disorders. Nevertheless, the rates of psychiatric disorders in the parents with bipolar disorder were similar to those reported in the adult bipolar literature (45, 46). Also, even though BIOS is not an epidemiological study, the lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders observed in the comparison parent group was similar to that reported in a recent large epidemiological study in the United States (47). Fourth, no direct observations of the preschoolers were available. Finally, although behavioral and mood disorders are identifiable in preschoolers, more research is needed on the way these disorders, particularly mania, manifest in preschoolers and on what would be the most appropriate methods and instruments to assess these conditions in this population.

Both biological parents of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had higher rates of psychopathology than comparison parents, and thus it is not surprising that their offspring also had significantly more psychopathology. In fact, after taking into account both biological parents' psychopathology, between-group differences in having any axis I disorder and disruptive behavior disorders were no longer significant. However, rates of ADHD remained significantly higher in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Studies of preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder that evaluated dimensional symptoms rather than categorical disorders have also shown that these children have symptoms frequently observed in children with ADHD, such as behavioral disinhibition, hyperactivity, and difficulty managing anger and hostile impulses (15, 17, 19).

It is not yet clear why the results of the BIOS preschool-age study contrast with those of the BIOS and other school-age high-risk studies (i.e., high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders) (14, 48–50). It is possible that the K-SADS-PL was not sensitive enough to detect mood and anxiety disorders in preschoolers. However, rates of disorders ascertained through the K-SADS-PL are similar to those found in epidemiological studies (19, 35), and one epidemiological study using an unmodified K-SADS-PL (51) diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders in preschoolers at rates similar to the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (19). It is also probable that in comparison with older children, nonspecific symptoms such as irritability, hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity are ubiquitous manifestations of externalizing as well as internalizing psychopathology in preschool children (9, 14, 52–55). In contrast, because of the emotional and cognitive developmental level in this population, more specific manic symptoms, such as grandiosity and elation, or depressive symptoms, such as hopelessness and severe melancholia, may not yet be evident, and if they are present, they are more difficult to ascertain (24). Thus, in BIOS, although these nonspecific externalizing symptoms may indeed be accounted for by early-childhood ADHD, it is also possible that they are prodromal or subthreshold symptoms of mood disorders, especially when accompanied by mood symptoms and a family history of mood disorders (8, 9, 14, 16, 53, 56–59). In fact, in BIOS, preschool children in the bipolar parent group with externalizing disorders had significantly more manic and depressive symptoms than offspring in the bipolar parent group without these disorders and offspring in the comparison parent group. As reported in the literature, these children are at high risk for developing mood disorders (60–64).

Only three offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had subthreshold mood disorders. However, these children have not reached the age of highest risk for developing bipolar and major depressive disorders, and it has been consistently shown that the rate of these disorders is likely to increase with age (5, 8, 9, 65, 66). Despite the above findings, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, and especially offspring with externalizing disorders, had significantly more severe manic (including elation) and depressive symptoms than offspring of comparison parents. However, it is important to note that, in general, the severity of individual manic symptoms was subclinical. Furthermore, additional research is needed to define the boundaries between bipolar symptoms (e.g., elation, grandiosity, irritability, and mood episodicity) and the expected broad mood fluctuations and normal fantasies about special powers and abilities and appropriately increased self-concept commonly observed in preschool children (24, 67).

Because BIOS is prospectively following all children, we will be able to address these developmental issues and delineate the types and severity of symptoms that predict subsequent conversion to bipolar disorder. Also, because approximately 70% of the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder in our sample did not have any diagnosable psychiatric illness and very few had subthreshold mood disorders, there is a window of opportunity for primary prevention in this high-risk population. Thus, psychosocial interventions aimed at helping preschool children regulate their mood, which have been found to be efficacious in preschoolers with disruptive behavior disorders and in older children with subthreshold mood disorders, and effective treatment of parental psychopathology may diminish the severity of, and perhaps delay or prevent the new onset of, psychopathology in preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (4, 24, 68–71).

1 : Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder, characteristics of second and third episodes, predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:1125–1133 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:582–590 Link, Google Scholar

3 : Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:846–871 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Prevention of bipolar disorder in at-risk children: theoretical assumptions and empirical foundations. Dev Psychopathol 2008; 20:881–897 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:287–296 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : Psychopathology in the adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. J Affect Disord 2004; 78:67–71 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Review of studies of child and adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord 2001; 3:325–334 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Psychopathology in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:554–561 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : The early manifestations of bipolar disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9:828–838 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 : Studies of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2003; 123C:26–35 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Psychopathology in the young offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a controlled pilot study. Psychiatry Res 2006; 145:155–167 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : A follow-up investigation of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:506–509 Link, Google Scholar

13 : Cognitive and social development in infants and toddlers with a bipolar parent. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1984; 15:75–85 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : Young children of affectively ill parents: a longitudinal study of psychosocial development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:68–77 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 : A developmental view of affective disturbances in the children of affectively ill parents. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:219–222 Link, Google Scholar

16 : Laboratory-observed behavioral disinhibition in the young offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a high-risk pilot study. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:265–271 Link, Google Scholar

17 : Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample. Pediatrics 2006; 117:2101–2110 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Diagnostic specificity and nonspecificity in the dimensions of preschool psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:1005–1013 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47:313–337 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 : Preschool psychopathology: lessons for the lifespan. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:961–966 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 : Preschool depression: homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:897–905 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : Preschool depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2006; 15:899–917 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 : Three clinical cases of DSM-IV mania symptoms in preschoolers. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007; 17:237–243 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 : Defining and validating bipolar disorder in the preschool period. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18:971–988 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : Mania in six preschool children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13:489–494 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 : Valproate in very young children: an open case series with a brief follow-up. J Affect Disord 2001; 67:193–197 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 : Preschool-onset mania: incidence, phenomenology, and family history. J Affect Disord 2004; 82(suppl 1):S35–S43 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 : The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229–1235 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 : Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 : A preliminary study of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children mania rating scale for children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003; 13:463–470 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 : Evaluation and comparison of psychometric instruments for pediatric bipolar spectrum disorders in four age groups. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2007; 17:853–866 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 : The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: test-retest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode Version. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:696–702 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 : Are oppositional defiant and conduct disorder symptoms normative behaviors in preschoolers? a comparison of referred and nonreferred children. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:356–358 Link, Google Scholar

34 : Dysthymic disorder in clinically referred preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1426–1433 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 : Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS-PL) for the assessment of preschool children: a preliminary psychometric study. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43:680–686 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 : Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1139–1148 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 : Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:795–804 Link, Google Scholar

38 : Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 2000 Google Scholar

39 : Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:879–883 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 : Four-Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975 Google Scholar

41 : Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence A Erlbaum Associates, 1988 Google Scholar

42 : Mothers' mental illness and child behavior problems: cause-effect association or observation bias? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:592–602 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 : Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:1038–1050 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 : Community versus clinic sampling: effect on the familial aggregation of anxiety disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63:884–890 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 : Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2007; 3:137–158 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 : Specificity of bipolar spectrum conditions in the comorbidity of mood and substance use disorders: results from the Zurich Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:47–52 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 : Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 : Psychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspring. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:453–460 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 : Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord (Epub ahead of print, Jun 19, 2009) Medline, Google Scholar

50 : Associations between bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1679–1681 Link, Google Scholar

51 : DSM-III-R disorders in preschool children from low-income families. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:620–627 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 : Early childhood temperament in pediatric bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychol 2008; 64:402–421 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 : Clinical outcomes of laboratory-observed preschool behavioral disinhibition at five-year follow-up. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:565–572 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 : Who are the children with severe mood dysregulation, aka "rages"? (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1140–1142 Link, Google Scholar

55 : Problem behaviors and peer interactions of young children with a manic-depressive parent. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:236–240 Link, Google Scholar

56 : Prospective study of prodromal features for bipolarity in well Amish children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:786–796 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 : Phenomenology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: complexities and developmental issues. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18:939–969 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 : Bipolar disorder and comorbid conduct disorder in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:715–723 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 : A 10-year prospective study of prodromal patterns for bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:1104–1111 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60 : Controlled study of switching from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder to a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype during 6-year prospective follow-up: rate, risk, and predictors. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18:1037–1053 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 : Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005; 46:1200–1210 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62 : Comorbidity of internalizing disorders in children with oppositional defiant disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 16:484–494 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63 : Ages of onset and rates of syndromal and subsyndromal comorbid DSM-IV diagnoses in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1486–1493 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64 : Chronic versus episodic irritability in youth: a community-based, longitudinal study of clinical and diagnostic associations. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006; 16:456–466 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 : Five-year prospective outcome of psychopathology in the adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord 2005; 7:344–350 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66 : Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:837–844 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67 : Mania and ADHD: comorbidity or confusion. J Affect Disord 1998; 51:177–187 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68 ;

69 : The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006; 74:401–415 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70 : Preventing depression in children through resiliency promotion: the Prevention Intervention Project, in The Effects of Parental Dysfunction on Children. Edited by McMahon RJPeters RD. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2003, pp 71–86 Google Scholar

71 : Prevention of pediatric bipolar disorder: integration of neurobiological and psychosocial processes. Ann NY Acad Sci 2006; 1094:235–247 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar