The Efficacy of Self-Help Group Treatment and Therapist-Led Group Treatment for Binge Eating Disorder

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this investigation was to compare three types of treatment for binge eating disorder to determine the relative efficacy of self-help group treatment compared to therapist-led and therapist-assisted group cognitive-behavioral therapy. Method: A total of 259 adults diagnosed with binge eating disorder were randomly assigned to 20 weeks of therapist-led, therapist-assisted, or self-help group treatment or a waiting list condition. Binge eating as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination was assessed at baseline, at end of treatment, and at 6 and 12 months, and outcome was assessed using logistic regression and analysis of covariance (intent-to-treat). Results: At end of treatment, the therapist-led (51.7%) and the therapist-assisted (33.3%) conditions had higher binge eating abstinence rates than the self-help (17.9%) and waiting list (10.1%) conditions. However, no between-group differences in abstinence rates were observed at either of the follow-up assessments. The therapist-led condition also showed more reductions in binge eating at end of treatment and follow-up assessments compared to the self-help condition, and treatment or waiting period completion rates were higher in the therapist-led (88.3%) and waiting list (81.2%) conditions than in the therapist-assisted (68.3%) and self-help (59.7%) conditions. Conclusions: Therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment for binge eating disorder led to higher binge eating abstinence rates, greater reductions in binge eating frequency, and lower attrition compared to group self-help treatment. Although these findings indicate that therapist delivery of group treatment is associated with better short-term outcome and less attrition than self-help treatment, the lack of group differences at follow-up suggests that self-help group treatment may be a viable alternative to therapist-led interventions.

Binge eating disorder is characterized by binge eating episodes, frequent comorbid obesity with associated medical problems (1 , 2) , high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (3) , and psychosocial impairment (4) . Several psychological treatments have been found to be helpful in treating this condition (5) , including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; 6 , 7) , interpersonal therapy (6) , dialectical behavior therapy (8) , and behavioral weight loss (9) . Although medications have been shown in several studies to reduce binge eating frequency (10 – 12) , pharmacological interventions appear to be less efficacious than evidence-based psychotherapy and have not been observed to improve remission rates when combined with CBT (7) .

In an attempt to develop less costly treatments that can be more easily disseminated, several investigations have found that cognitive-behavioral and psychoeducational techniques administered in self-help (13) or guided self-help formats have led to improvements in binge eating in patients with binge eating disorder (14 – 17) . In all but one of these studies (17) , these self-help interventions were administered individually. However, most psychotherapy studies for individuals with binge eating disorder have been conducted using group modalities. The administration of self-help treatment in a group setting has a number of advantages, including further reductions in cost, the potential for broader dissemination, and interpersonal support for group members. In examining the potential utility of group self-help for the treatment of binge eating disorder, our preliminary investigation found that a group self-help intervention was comparable to therapist-led and therapist-assisted group CBT at end of treatment (18) and over a 1-year follow-up period (17) . The aim of the present study was to compare therapist-led and self-help group CBT for binge eating and associated symptoms, as well as to examine the viability and potential efficacy of therapist-assisted and partial self-help group treatment.

Method

Participants

Participants (N=259) were adults recruited from two clinical sites, one in Minnesota and the other in North Dakota. Potential participants were recruited from the community through advertisements as well as referrals from local eating disorder treatment clinics and other health professionals. For inclusion, participants had to meet full DSM-IV criteria for binge eating disorder as assessed by the Eating Disorder Examination (19) and have a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 (kg/m 2 ). Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorder; current diagnosis of substance abuse or substance dependence; medical or psychiatric instability, including acute suicide risk; current psychotherapy; or current participation in a formal weight loss program. Participants who were on a stable dose of antidepressant medication for a minimum of 6 weeks were allowed to participate.

Of the 1,917 individuals screened by phone, 1,519 were ineligible or not interested in participating ( Figure 1 ). Of the 398 who attended initial orientation meetings, 367 were assessed by interview; of these, 108 were excluded or declined to participate, resulting in 259 who were enrolled in the study.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at both sites. Written informed consent was obtained during the orientation meeting after potential participants received a detailed description of the study.

Assessments

The primary outcome measure was the frequency of binge eating episodes as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination at baseline, at end of treatment (or end of waiting period for participants assigned to the waiting list condition), and at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments. Eating pathology was also assessed using the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (20) . Additional secondary outcome measures included BMI, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report score (21) , Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire score (22) , and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life–Lite score (23) . Participants completed all of these measures at baseline, at end of treatment or waiting period, and at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Experienced graduate-level assessors blind to participant randomization conducted the interviews. Throughout the study, assessors met in person and communicated between sites by teleconference and e-mail in order to prevent drift. All assessment interviews were audiotaped. Interrater reliability ratings were conducted on a random sample (20%) of Eating Disorder Examination audiotapes. Interrater reliability (based on intraclass correlation coefficients) for the Eating Disorder Examination subscales and global score ranged from 0.955 to 0.982.

Randomization and Treatment

After completing the assessment protocol, participants were randomly assigned to one of three active treatments or the waiting list condition by the independent biostatistician (R.D.C.). An adaptive randomization strategy was used in which the probability of assignment to any treatment condition at a given point in time was inversely related to the relative proportion of participants previously assigned to that condition. Assignment sequence was shielded from all investigators, study personnel, therapists, and participants until time of randomization.

Participants randomized to the waiting list condition were informed that they would receive therapist-led group treatment at the end of the 20-week waiting period. Data collected from the waiting list participants after the waiting period were not included in these analyses.

All active treatments consisted of 15 group sessions of 80 minutes’ duration over a 20-week period, with weekly sessions for the first 10 weeks and biweekly sessions for the remaining 10 weeks. The mean group size was six, and the range was two to 11. The content of the three active treatment conditions was identical; only treatment delivery varied. The initial sessions focused on behavioral and cognitive interventions; the middle sessions emphasized techniques to target associated problems, including stress management and body image; and the final two sessions included strategies to prevent relapse (24) . Each 80-minute session was divided into two equal segments, with the first focusing on psychoeducation and the second on homework review and discussion. All participants in active treatment received identical workbooks and homework assignments.

In the therapist-led CBT groups, a doctoral-level psychotherapist provided psychoeducation during the first half of each session and homework review and discussion during the second half. In the therapist-assisted CBT groups, participants watched a psychoeducational videotape (a specific tape was designed for each session) during the first half of each session, and during the second half a doctoral-level psychotherapist joined the group to review homework and lead a discussion. In the self-help groups, participants watched a psychoeducational videotape during the first half of each session and conducted their own homework review and discussion during the second half. Participants in the self-help groups were given comprehensive instructions with detailed guidelines and time allotments for each discussion session. In addition, group members were assigned the role of lead facilitator on a rotating basis. Participants assigned to the waiting list condition received therapist-led treatment at the end of the 20-week waiting period.

Doctoral-level therapists were initially trained by didactic and discussion sessions and led a practice group before administering the treatment for this study. Therapists met regularly with the supervisor (C.B.P.) in person and by teleconference to discuss the implementation of the treatment manual, ensure treatment fidelity, and prevent center drift. All group sessions were audiotaped. Several sessions from each therapist-led and therapist-assisted group (a total of 106 tapes) were reviewed by the supervisors (C.B.P. and S.J.C.) and rated on a 7-point Likert scale (with 7 the highest rating). The overall therapist rating was 6.32 (SD=0.38); subscale ratings were as follows: adherence, mean=6.19 (SD=0.93); comprehensiveness, mean=6.00 (SD=0.86); effective communication, mean=6.58 (SD=0.62); therapeutic technique, mean=6.46 (SD=0.69); and rapport, mean=6.40 (SD=0.55).

Statistical Analyses

Power analysis for this study was based on two previous studies conducted by our research group evaluating the effects of psychotherapeutic and self-help treatment (18 , 25) on binge eating. Assuming a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, we calculated that a sample size of 65 per group (260 total) would provide a power greater than 0.99 to detect posttreatment differences in binge eating frequencies between active treatments and the waiting list condition, and a power of 0.88 to detect differences between active treatments (26) .

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared across treatment assignment and site using analysis of variance for continuous measures and logistic regression for dichotomous variables. Models included main effects for treatment group and site and a treatment group-by-site interaction.

The primary efficacy analysis was based on the intent-to-treat sample. Where posttreatment or follow-up data were missing, the baseline value was carried forward. Three primary outcome variables obtained from the Eating Disorder Examination were evaluated: binge eating episodes in the previous 28 days; binge eating days in the previous 28 days; and abstinence, defined as no binge eating episodes in the past 28 days. Analysis of covariance was used to compare the four groups on binge eating episodes and days at end of treatment or waiting period, controlling for baseline values, site, and gender (based on baseline differences between groups). Because of positive skew, binge eating episodes and days were log-transformed prior to analysis. Pairwise post hoc comparisons between groups were based on covariate-adjusted contrasts using a significance level of 0.008 (0.05/6) at end of treatment and 0.017 (0.05/3) at follow-up assessments. Logistic regression analysis was used to compare groups on abstinence rates at end of treatment waiting period, controlling for site and gender.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Randomization

Of the 259 participants, 227 (87.6%) were women. The average age was 47.1 years (SD=10.4, range=19–65). Most participants were Caucasian (96.1%), had a college degree or higher (54.9%), were employed full-time (61.0%), and were taking antidepressant medication (78.8%). The average BMI was 39.0 (SD=7.8, range=24.8–72.6).

A total of 69 participants were assigned to the waiting list condition (31 in Minnesota, 38 in North Dakota), 67 to the self-help condition (15 in Minnesota, 52 in North Dakota), 63 to the therapist-assisted condition (18 in Minnesota, 45 in North Dakota), and 60 to the therapist-led condition (37 in Minnesota, 23 in North Dakota). (Table S1, in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article, presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by treatment group and treatment site.) Participants from the Minnesota site were older on average (F=6.12, df=1, 251, p=0.014; partial eta-squared=0.024) and had significantly higher restraint scores on the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (F=12.21, df=1, 229, p=0.001; partial eta-squared=0.051). The only difference in baseline characteristics between treatment groups was on gender distribution (χ 2 =13.97, df=3, p=0.003; Nagelkerke R 2 =0.146), where the percentage of women in the therapist-led group (100%) was higher than that for waiting list (81.2%) and therapist-assisted (81.0%) groups.

Attrition

Of the 259 participants, 192 (74.1%) were assessed at end of treatment or waiting period ( Figure 1 ). A larger number of participants completed the therapist-led (N=53; 88.3%) and waiting list (N=56; 81.2%) conditions than the therapist-assisted (N=43; 68.3%) and self-help (N=40; 59.7%) conditions (χ 2 =16.50, df=3, p=0.001). In comparison to those who completed the assessment at end of treatment or waiting period, those who did not complete the assessment were younger (mean=44.4 years compared with mean=47.8 years; F=5.44, df=1, 257, p=0.020; partial eta-squared=0.021) but did not differ on other demographic or clinical characteristics.

Abstinence Rates

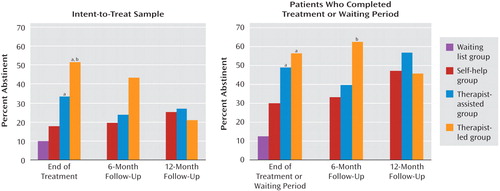

Figure 2 presents the percentages of participants who were abstinent from objective binge eating episodes in the previous 28 days at end of treatment or waiting period, at the 6-month follow-up, and at the 12-month follow-up by treatment group; data are shown for both the intent-to-treat sample and those who completed treatment or the waiting period. In the intent-to-treat sample, abstinence rates were as follows: at end of treatment or waiting period, therapist-led group, 51.7%; therapist-assisted group, 33.3%; self-help group, 17.9%; waiting list group, 10.1%; at the 6-month follow-up: therapist-led group, 43.3%; therapist-assisted group, 23.8%; self-help group, 19.4%; at the 12-month follow-up, therapist-led group, 20.8%; therapist-assisted group, 27.0%; self-help group, 25.4%. Posttreatment abstinence rates were significantly different across treatment groups after controlling for site and gender both in the intent-to-treat sample (χ 2 =24.19, df=3, p<0.001) and for those who completed treatment (χ 2 =22.28, df=3, p<0.001). The therapist-led and therapist-assisted groups had significantly (p<0.008) higher abstinence rates than patients in the waiting list group for both analyses. In addition, abstinence rates were significantly higher in the therapist-led group than in the self-help group in the intent-to-treat sample but not among those who completed treatment. Differences in abstinence rates at the 6-month follow-up approached significance in the intent-to-treat analysis (χ 2 =5.55, df=2, p=0.062) and reached statistical significance in the analysis of those who completed treatment (χ 2 =6.69, df=2, p=0.035), with the therapist-led group having significantly higher abstinence rates than the self-help group (p=0.013). No differences between abstinence rates at the 12-month follow-up were observed either for the intent-to-treat group or for those who completed treatment. No site differences were observed in abstinence rates.

p<0.008 compared with the waiting list group.

p<0.008 compared with the self-help group.

Binge Eating Frequency

Table 1 presents average objective binge eating days and episodes at baseline, at end of treatment or waiting period, at the 6-month follow-up, and at the 12-month follow-up by treatment group for the intent-to-treat sample. Significant differences between treatment groups at the posttreatment assessment were found for both objective binge eating days (F=14.97, df=3, 252, p<0.001; partial eta-squared=0.151) and episodes (F=15.29, df=3, 252, p<0.001; partial eta-squared=0.154). Post hoc analyses indicated that 1) the therapist-led group had greater reductions in objective binge eating days and episodes than the self-help and waiting list groups; 2) the therapist-assisted group had greater reductions in objective binge eating days and episodes than the waiting list group; and 3) the self-help group had greater reductions in objective binge eating episodes (but not days) than the waiting list group. No significant differences in binge eating frequencies were found between treatment groups at either of the follow-up assessments. No site differences were observed at end of treatment or waiting period or at follow-up assessments.

Secondary Outcomes

Few differences between treatment groups were observed in secondary outcome measures at end of treatment or waiting period ( Table 1 ). The therapist-led group experienced significantly greater reductions than the waiting list group on the Eating Disorder Examination restraint subscale (F=3.46, df=3, 252, p=0.017; partial eta-squared=0.040) and global score (F=4.04, df=3, 252, p=0.008; partial eta-squared=0.046). In addition, both the therapist-assisted and therapist-led groups experienced greater reductions than the waiting list group in disinhibition scores on the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (F=5.78, df=3, 230, p=0.001; partial eta-squared=0.070). No differences in secondary outcome measures, including depression, quality of life, and BMI, were observed between treatment groups at either follow-up assessment.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral techniques can be implemented in therapist-led, therapist-assisted, and structured self-help group formats for the treatment of patients with binge eating disorder. Although all three active treatments appear to have had better outcomes than the waiting list condition on most measures of binge eating, patients in the therapist-led group had the highest rate of abstinence and the fewest dropouts at end of treatment. No significant differences were observed between treatment groups at follow-up on any of the primary or secondary outcome measures. Although improvements in binge eating were notable, co-occurring symptoms, including depression and low self-esteem, did not improve more significantly in the active treatment conditions than in the waiting list condition and did not differ among the treatments at follow-up. Similar to previous studies that have used cognitive-behavioral and self-help approaches to treat binge eating disorder, BMI did not change significantly over the course of treatment or follow-up.

These findings suggest that groups for individuals with binge eating disorder with reduced or no therapist involvement may be used as alternative treatments and that psychoeducation for the treatment of binge eating can be delivered in a group format using video or other technology. However, the presence of a therapist may enhance short-term abstinence and reduce the likelihood of dropout. Nonetheless, structured self-help groups may be useful in settings in which trained therapists are not available and may improve the dissemination of efficacious treatments for those with binge eating disorder. These findings are also consistent with findings in previous studies of binge eating disorder (27) as well as other areas of behavioral health (28) that self-help approaches are a viable alternative to therapist-delivered treatment.

This study is among the first to examine the delivery of therapist-assisted and self-help interventions to patients with binge eating disorder in a group format. Additional strengths of this investigation include its sample size and its rigorously conducted assessment and interventions. Several limitations should be noted. The participants were primarily female, Caucasian, and well educated, which may limit the generalizability of these findings. In addition, because the waiting list group was given treatment at the end of the 20-week waiting period, whether that group would have shown improvement and spontaneous recovery over the course of follow-up if they had not received treatment is unknown. Without a control group during the follow-up phase, it is impossible to be certain that the active interventions actually yielded long-term treatment effects. Although retaining a longer-term waiting list control group raises potential ethical concerns, this possibility warrants consideration in future investigations to demonstrate treatment efficacy. Finally, the self-help group approach used in this investigation was highly structured, with significant accountability required of participants. For this reason, these results are not necessarily reflective of self-help groups in the community, which tend to be less structured and more informal.

Because the abstinence rates observed in this study were lower than those seen with individual approaches to psychotherapy, guided self-help, and self-help (14 , 15) , a larger randomized study comparing individuals with group-based self-help is necessary. The dropout rates in this study were also notable, making interpretation of the follow-up data less clear, which raises concerns about the acceptability of group-based approaches with this intervention and suggests that future investigations examine ways to improve attrition through enhanced efficacy and acceptability. In addition, further research is needed to understand the cost-effectiveness of these approaches given the fact that therapist-led treatments are generally more expensive than self-help approaches. Research is also needed on innovative therapy delivery models to increase the accessibility and dissemination of treatment and the incorporation of these strategies into stepped-care designs. Finally, effectiveness trials are needed to examine the extent to which these models can be used in clinical and community settings.

1. Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Health problems, impairment, and illness associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med 2001; 31:1455–1466Google Scholar

2. Bulik CM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T: Medical morbidity in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2003; 34(suppl):S39–S46Google Scholar

3. Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL: Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1472–1479Google Scholar

4. Wilfley DE, Wilson GT, Agras WS: The clinical significance of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Dis 2003; 34(suppl):S96–S106Google Scholar

5. Wonderlich SA, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Peterson C, Crow S: Psychological and dietary treatments of binge eating disorder: conceptual implications. Int J Eat Dis 2003; 34(suppl):S58–S73Google Scholar

6. Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE: A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psych 2002; 59:713–721Google Scholar

7. Grilo CG, Masheb RM, Wilson GT: Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:301–309Google Scholar

8. Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM: Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001; 69:1061–1065Google Scholar

9. Marcus MD, Wing RR, Fairburn CG: Cognitive behavioral treatment of binge eating vs behavioral weight control in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Ann Behav Med 1995; 17(suppl):S090Google Scholar

10. Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PE Jr, Carter WP, Mitchell JE, Strakowski SM, Pope HG Jr, Coleman BS, Jonas JM: Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1756–1762Google Scholar

11. McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1004–1006Google Scholar

12. McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE Jr, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, Kamin M, Hudson JI: Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:255–261Google Scholar

13. Fairburn CG: Overcoming Binge Eating. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

14. Carter JC, Fairburn CG: Cognitive behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:616–623Google Scholar

15. Grilo CM, Masheb RM: A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43:1509–1525Google Scholar

16. Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Gilbert JS, Labouvie E: Guided and unguided self-help for binge eating. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:259–272Google Scholar

17. Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Crow SJ, Thuras P: Self-help versus therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder at follow-up. Int J Eat Dis 2001; 30:363–374Google Scholar

18. Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP: Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led vs self-help formats. Int J Eat Disord 1998; 24:125–136Google Scholar

19. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, 12th ed, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1996, pp 317–360Google Scholar

20. Stunkard AJ, Messick S: Three factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985; 29:71–83Google Scholar

21. Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C: The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:65–87Google Scholar

22. Rosenberg M: Conceiving the Self. New York, Basic Books, 1979Google Scholar

23. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR: Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001; 9:102–111Google Scholar

24. Mitchell JE, Devlin MJ, de Zwaan M, Crow SJ, Peterson CB: Binge-Eating Disorder: Clinical Foundations and Treatment. New York, Guilford, 2008Google Scholar

25. Mitchell JE, Fletcher L, Hanson K, Mussell MP, Seim H, Crosby R, Al-Banna M: The relative efficacy of fluoxetine and manual-based self-help in the treatment of outpatients with bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21:298–304Google Scholar

26. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

27. Sysko R, Walsh BT: A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2008; 41:97–112Google Scholar

28. Lorig K, Ritter PL, Plant K: A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53:950–957Google Scholar