Performance-Based Measurement of Functional Disability in Schizophrenia: A Cross-National Study in the United States and Sweden

Abstract

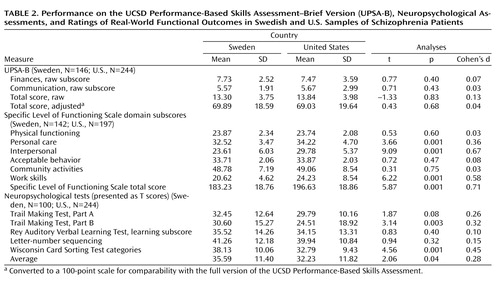

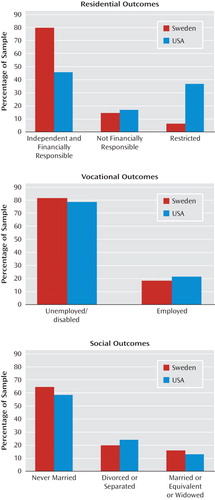

Objective: Recent advances in the assessment of disability in schizophrenia have separated the measurement of functional capacity from real-world functional outcomes. The authors examined the similarity of performance-based assessments of everyday functioning, real-world disability, and achievement of milestones in people with schizophrenia in the United States and Sweden. Method: The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment–Brief Version (UPSA-B) and a neuropsychological assessment were administered to schizophrenia patients living in rural areas in Sweden (N=146) and in the New York City area (N=244), and patients’ functioning was rated by their case managers. Information from records and case managers was used to determine the frequency of living independently, working, and having ever experienced a stable romantic relationship. Results: Performance on the UPSA-B was essentially identical in the two samples (New York, mean score=13.84; Sweden, mean score=13.30), as were scores on the case manager ratings of everyday activities (New York, mean=49.0; Sweden, mean=48.8). The correlations between UPSA-B score, neuropsychological test performance, and case manager ratings did not differ across the two samples. The proportion of patients who had never had a close relationship and the rate of vocational disability were also nearly identical. However, while 80% of the Swedish patients were living independently, only 46% of the New York patients were. Conclusions: While scores on performance-based measures of everyday living skills were similar in people with schizophrenia across cultures, real-world residential outcomes were very different. These data suggest that cultural and social support systems can lead to divergent real-world outcomes among individuals who show evidence of the same levels of ability and potential.

People with severe mental illnesses suffer disability in multiple everyday domains. Recent studies of real-world disability have focused on the relationships between impaired performance on neuropsychological tests and functional skills (or functional capacity) (1 – 3) . Functional capacity measures are standardized tests of everyday activities, such as financial management and medication management; they are clearly face-valid predictors of everyday functioning, but other environmental and experiential factors may cause discrepancies between what people can do and what they actually do in their everyday lives. For instance, a person with schizophrenia may be capable of independent medication management but may not have the opportunity to do so because of rules and operating procedures at his or her board-and-care facility.

The results of studies examining the correlation between functional capacity and neuropsychological measures have been remarkably consistent in finding substantial correlations between these two domains of functioning (3 – 7) . Correlations between these two sets of measures and various real-world outcomes have been smaller and more variable, with the studies rating real-world outcomes with self-report methods generally yielding smaller correlations.

Despite the relationship between neuropsychological outcomes, functional capacity outcomes, and real-world outcomes, in most studies only a small amount of variance in real-world outcomes is accounted for by the other two sets of variables. Even patients whose neuropsychological functioning is in the normal range have substantial disability in certain domains of everyday functioning (8) . Several other variables clearly mediate the relationships between skills competence and performance in real-world settings, including the motivation to engage in real-world functional activities; other symptoms, such as depression and negative symptoms (9 , 10) ; and other skills, such as social cognitive abilities (11) . Perhaps the most important of these influences is the societal context, which includes health insurance, disability policies, and cultural attitudes toward disability and mental illness. In the large Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, the most potent predictor of current unemployment in individuals with schizophrenia was the receipt of disability compensation (12) , which is often linked to the individual’s health insurance coverage. This is a finding consistent with previous research (13) .

Social service plans are highly divergent across countries, with some countries having national health insurance and others having much more haphazard systems. The prevalence of schizophrenia and the distributions of classical schizophrenia symptoms are quite consistent across countries (14) , and cross-national studies of cognitive performance in schizophrenia have found substantial similarity across different Western countries (15) . However, since elements of everyday functional disability are multiply determined, it may be that the influences of social services are different across countries. In line with this hypothesis, we previously reported that several elements of disability in everyday skills (i.e., social and self-care functions) were differentially impaired across long-stay institutionalized schizophrenia patients in the United States and the United Kingdom (16) . Cognitive impairment was consistent in severity across the patients in the two countries, and despite the differences in severity of disability, the correlations between cognitive impairments and the severity of the different aspects of disability were essentially the same across countries. We suggested that environmental differences in the long-stay hospital system drove variations in the topography of impairments in everyday skills across the two countries and systems of care.

In this article, we present the results of a cross-national study conducted in the United States and Sweden examining the severity of impairments in performance on structured examinations of everyday living skills (i.e., functional capacity), the level of observed disability in everyday living, performance on neuropsychological tests, and real-world functional milestones (e.g., independent living) and their correlations. We created a translated version of a functional capacity measure, the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment–Brief Version (UPSA-B; 17), and a translated version of a real-world outcomes clinical rating scale, the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (18) , for use in patients in Sweden. Patients in both countries performed the functional capacity measure and their case managers rated their functioning in several domains, including residential, vocational, and social functioning. Real-world functioning milestones, including independence in living situation, relationship history, and current employment status, were all collected from records, interviews, and case manager reports. Of additional interest was the fact that the Clinical Long-Term Investigation of Psychosis in Sweden sample was from a largely rural area (Trollhättan) and the U.S. sample was collected in New York City and its immediate suburbs. This is, to our knowledge, the first study that directly compared functional capacity, clinical ratings of disability, and functional outcome milestones across two different countries whose health care systems and levels of social support for people with mental illness are very divergent. Thus, this study provides a wide-ranging test of the cross-cultural generalizability and utility of functional capacity assessments.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were older ambulatory schizophrenia patients. Exclusion criteria for this study included a primary DSM-IV axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; a Mini-Mental State Examination score below 18; or any medical illnesses that might interfere with the assessment. All U.S. participants were in outpatient treatment at the time of recruitment at a Department of Veterans Affairs site, a New York state site, or an academic research site. Patients in Sweden were receiving care from the county council-funded outpatient clinics at NU Health Care Hospital. Outpatient status was defined as living outside of any institutional setting, including a nursing home. All participants received a complete explanation of the testing procedures and signed an informed consent form approved by the institutional review board at each research site.

Patients in both samples were excluded if they had a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, active substance abuse or a lifetime history of substance dependence, or any disease of the CNS, including a history of stroke, degenerative dementia such as Alzheimer’s Disease, or Parkinson’s disease.

All participants met diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV). For the U.S. patients, the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH; 19 ) was completed by a trained research assistant, and diagnosis was confirmed with a senior clinician. For the Swedish patients, diagnoses were generated according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and the Decision Trees for Differential Diagnosis by their psychiatrists. Data for these analyses came only from patients who were receiving case management services and were actively involved in psychiatric rehabilitation services. The case managers were used as the informants for the real-world functional status ratings. All patients were receiving treatment with antipsychotic medications (either first- or second-generation agents) at the time of their assessments.

Performance-Based Measure of Functional Capacity

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment battery (UPSA; 20 ) is designed to directly assess functional skills competence among the severely mentally ill. It was designed for outpatients and measures performance in a number of domains of everyday functioning through the use of props and standardized skills performance situations. In this study, the UPSA-B (17) was used, which contains two of the original UPSA domains, based on two recent studies (17 , 21) suggesting that these two subscales alone correspond excellently with the total score. In the finance domain, the patient must count out given amounts from real currency, make change, and fill out a check to pay a utility bill. The communication domain involves a series of role play situations requiring that the patient make emergency calls, call directory assistance to request a telephone number, call the number, and then reschedule a medical appointment. We standardized the scores to a 100-point scale, like the original five-subtest UPSA, thus allowing comparisons to previous results. This total score was used as our dependent measure. In Sweden, occupational therapists performed the assessment.

Real-World Functional Outcomes

We used the Specific Level of Functioning Scale to examine everyday functioning in the real world. This scale is a 43-item observer-rated report of a patient’s behavior and functioning in six domains: physical functioning (e.g., vision, hearing), personal care (e.g., toileting, eating, grooming), interpersonal relationships (e.g., initiating, accepting, and maintaining social contacts; communicating effectively), social acceptability (e.g., verbal and physical abuse; repetitive behaviors), participation in community activities (e.g., shopping, using the telephone, paying bills, use of leisure time, use of public transportation), and work skills (e.g., following verbal instructions, completing tasks with minimal supervision, being punctual). Ratings are made on a 5-point Likert scale by the third-party informant on the basis of the amount of assistance the patient needs to perform real-world skills (personal care, activities), effects of the illness on daily living (physical functioning), or frequency of a behavior (interpersonal relationships, social acceptability, work skills). Higher scores reflect less impairment and more independence. The Specific Level of Functioning Scale has been shown to be related to neuropsychological performance and scores on functional capacity measures (5 , 8 , 9) . For all participants in this study, a case manager for the patient completed the scale, and all case managers indicated that they knew the patient “very well.” Case managers were unaware of the patient’s performance on cognitive and functional capacity measures, and the testers and interviewers who completed and scored all other aspects of assessment were unaware of the case managers’ ratings.

Real-World Milestones

In addition to the dimensional approach to rating real-world behavior with the Specific Level of Functioning Scale, we used a categorical ranking of milestone achievements, derived from a combination of self-report, case-manager, and chart data, that we employed in a previous study (8) . Independent living status was assessed by whether the patient lived in restrictive or supported housing as well as whether he or she was at least partially financially responsible for the residence. Patients were classified as living in restricted housing, living independently but not financially supporting the residence, or living independently and financially supporting the residence. Current work status was classified as unemployed or employed at least part time. Marital status was classified as married or widowed, divorced or separated, or never married.

Translation of Instruments

The English version of the UPSA-B requires manipulation of currency, paying bills, and communication, including emergency communication. In order to have the Swedish version be as similar as possible to the original, all currency amounts were retained and expressed in terms of the Swedish krona (which is also a decimal currency system, like the U.S. dollar). The bill to be paid was modified to look like a Swedish bill, and emergency communication items were modified to be congruent with the local requirements.

Instructions and scoring criteria for the UPSA-B and the Specific Level of Functioning Scale were translated into Swedish. For the UPSA-B, two of the Swedish authors (L.H. and T.N.) performed the translation together with a professional translator and in contact with one of the U.S. authors (C.R.B.). For the Specific Level of Functioning Scale, the same two Swedish authors and the translator completed the translation. The two instruments were then back-translated and checked by the Swedish authors to ensure comparability with the original instruments.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Both samples were examined with a neuropsychological assessment, which was somewhat different in each country. The tests that overlapped were the Trail Making Test, Parts A and B (22) ; the WAIS letter-number sequencing subtest; the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (23) ; the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, 128-card version (24) ; and the WAIS vocabulary subtest. These instruments had been previously translated into Swedish and were in clinical use in Sweden. All raw scores on the neuropsychological tests were converted to age-, education-, and gender-corrected standardized T scores from published U.S. norms. We used U.S. norms because of the standard practice in the Nordic countries of using U.S. norms for clinical assessment (personal communication from Erik Hessen, November 2008). We created a composite score for the neuropsychological measures by averaging the T scores across the tests that were administered to both samples. Since these T scores are demographically corrected, we did not perform analysis of covariance with demographic factors.

Sample Overlap

We reported data from the U.S. sample in a previous study (8) . For that study, we reported all analyses of real-world outcomes and performance-based measures with patients subdivided according to whether or not they met criteria for normal neuropsychological functioning and symptomatic remission. As a part of the Clinical Long-Term Investigation of Psychosis in Sweden, the Swedish sample was collected specifically to be assessed with the functional capacity and real-world outcomes assessment for this research project.

Results

The basic demographic characteristics of the sample, including vocabulary performance, are presented in Table 1 . As would be expected, 100% of the Swedish patients were Caucasian, and the U.S. sample was more ethnically diverse. The Swedish patients were somewhat younger and slightly better educated, on average, and more likely to be female compared to the U.S. sample.

Performance on the various assessments is summarized in Table 2 . As can be seen in the table, t tests showed that UPSA-B scores in the two countries were essentially identical, both on a raw score basis and when the scores were converted into the UPSA-B’s 100-point scale. Impairments in physical functioning, acceptable behavior, and everyday activities were also essentially identical across the two countries, while the U.S. patients were rated by their case managers as less impaired in basic activities of daily living, social activities, and work-related activities. In contrast, neuropsychological performance was poorer on some of the tests in the U.S. sample, with the composite T score suggesting significantly poorer performance on the part of the U.S. patients.

While total scores on the Specific Level of Functioning Scale reflected significantly more impairment in the Swedish sample, some of the individual subscales did not differ between the two samples, including physical functioning, socially acceptable behavior, and everyday living skills, which measures readiness for independent living. The effect sizes of the differences for the subscales that differed across the countries were moderate for work and basic activities of daily living and large for social functioning. In contrast, the effect sizes for neuropsychological performance were large for two variables, very small for two, and small (and nonsignificant) for one individual variable and on the composite score.

Figure 1 presents the residential, vocational, and social outcomes for the Swedish and U.S. samples. Social and vocational outcomes were essentially identical in the two samples. Where the outcomes diverged considerably was in the area of residential status. The majority of the Swedish patients were living independently and were financially responsible for their housing. The proportion living in restricted settings was considerably greater in the U.S. sample.

Table 3 presents the correlations between composite neuropsychological performance, total scores on the UPSA-B, and total scores on the Specific Level of Functioning Scale for the two samples. The correlations were very similar across the two countries, and none of the correlations between any of the pairs of variables in the two samples were statistically significantly different using the two-sample z test for the significance of the difference between correlations (all z values <1.21; all p values >0.35).

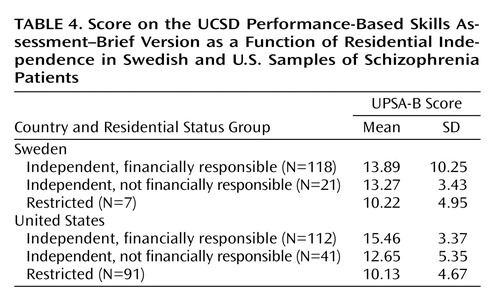

Table 4 summarizes the association between UPSA-B scores and independent living status for the Swedish and U.S. patients. We used one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), followed by Tukey post hoc tests within each sample to examine the differences in UPSA-B scores associated with the three levels of independent living. We chose not to use a status-by-country ANOVA because of the very unbalanced cell sizes. For the Swedish patients, there was no statistically significant difference across the three residential status groups in UPSA-B scores. Given the lack of homogeneity of variance across the cells, we used a nonparametric analysis, the Kruskal-Wallis H test. The results of this analysis were also nonsignificant. When the same ANOVA was performed in the U.S. sample, the results were statistically significant (F=4.94, df=2, 203, p<0.002). The follow-up Tukey tests indicated that each of the three groups was significantly (p<0.05) different from the groups immediately adjacent in terms of residential status. There was essentially no difference in the UPSA-B scores of patients in the United States and Sweden who were living in restricted housing environments. The main differences in UPSA-B scores appear to be due to the association between residential outcomes and UPSA-B scores in the U.S. patients, which resulted in the independently residing U.S. patients having the highest scores.

Discussion

The results of this study include several potentially important findings. The performance of people with schizophrenia on a well-validated scale of functional capacity in the domains of everyday living skills was essentially identical between samples in rural Sweden and New York City. Case manager ratings of the ability of these patients to function in terms of everyday living skills were also essentially identical for the two samples. The correlation between the different domains of the functional outcomes construct—cognitive abilities, functional capacity, and case manager ratings of real-world functioning—was essentially identical in these two samples as well. Differences in performance on neuropsychological tests were modest, and the correlations between neuropsychological performance and measures of functional capacity and real-world outcomes were also essentially the same in the two countries. An additional important finding, which renders the similarities in these multiple abilities even more important, is that there were substantial differences in residential outcomes between the two samples. These differences in residential outcomes, very likely based on differences in social services systems, led to no association between performance on structured tests designed to measure everyday living skills and residential outcomes in people with schizophrenia in Sweden.

While there are essentially no differences in the ability to live independently (in terms of both functional capacity assessments and case manager ratings), outcomes appear markedly more favorable in the Swedish sample. There was essentially no difference in UPSA-B performance scores between U.S. and Swedish patients who lived in restricted settings, which suggests that the complete inability to live independently may not be influenced by social service systems. In contrast, there was a clear functional capacity performance gradient associated with residential outcomes in the U.S. sample. This finding is interesting given that independent living ability was the only one of the three domains of real-world functional milestones measured in this study (social outcome, employment, and residential status) that was strongly associated with the presence of cognitive performance in the U.S. sample in our previous report (8) . Clearly these results do not necessarily apply across all countries and systems of care, and a comparison of rural and urban outcomes in either the United States or Sweden could help to unconfound rural/urban living status and differences in national health care policies.

Considerable evidence for the validity of the UPSA-B accrues from these findings, which suggests that this instrument measures some performance-based abilities that are consistent across substantial differences in culture. In order to perform this study, the subtasks from this instrument not only were translated into Swedish, but they also required modification of the stimuli in accordance with differences in financial requirements and communication demands across the two countries. The results suggest that this process may well be practical in other Western cultures as well. Differences in neuropsychological performance across the two countries were modest when corrected for demographic factors.

These findings have several implications for improvements in real-world outcomes following cognitive-enhancement or skills-development treatments. Equivalent improvements in ability lead to very different changes in real-world functional outcomes depending on other characteristics of the environment. As Rosenheck et a1. (12) demonstrated, employment outcomes in the United States are strongly associated with disability compensation, and this is particularly true for disability compensation that is linked to health insurance coverage. Other factors are probably involved as well. The health care system in Trollhättan is more generous with compensation than U.S. health care systems, with disability compensation in this part of Sweden at approximately US$1,000 per month. Moreover, the cost of living is markedly lower in Trollhättan (where a two-bedroom apartment costs approximately US$650 per month) than in New York City and its environs. Also, the local health authority provides disabled schizophrenia patients with 93% of their monthly rent, up to US$800 per month. The requirements associated with finding and paying for an apartment in the New York City metropolitan area are daunting for healthy individuals and much more challenging for individuals with disabling psychiatric symptoms and chronic unemployment. These differences in social support for people with mental illness have a clear and strong signal in terms of real-world functional outcomes. In contrast, other social and vocational milestones appear to occur with similar frequency in the two countries.

These data are consistent with the notion that ability-based measures may give a less confounded signal of functional potential than aspects of real-world community functioning (25 , 26) . Given that these data suggest negligible differences in the ability to perform everyday living skills in the assessment setting and marked differences in residential outcomes, it appears likely that residential outcomes, like employment outcomes, may be driven by factors other than ability. These findings also suggest that changes in the ability to perform everyday living skills are a central feature of schizophrenia, much like neurocognitive impairments. Although neuropsychological and functional capacity abilities are correlated, much as negative symptoms and neuropsychological deficits are, they appear to be separable domains of functioning that should be considered independently of their correlates. Previous research has shown that interventions that modify level of social support lead to functional gains in people with schizophrenia (27) . Research will need to continue to address the impact of social and cultural support mechanisms on outcomes, and multinational treatment studies will need to carefully consider the potential impact of these differences in social support for individuals with schizophrenia, both for the outcomes of treatment and for the selection of potential study participants.

1. Velligan DI, Diamond P, Glahn DC, Ritch J, Maples N, Castillo D, Miller AL: The reliability and validity of the Test of Adaptive Behavior in Schizophrenia (TABS). Psychiatry Res 2007; 151:55–66Google Scholar

2. Bellack AS, Sayers M, Mueser KT, Bennett M: An evaluation of social problem solving in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:371–378Google Scholar

3. Keefe RSE, Poe M, Walker TM, Kang JW, Harvey PD: The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:426–432Google Scholar

4. McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV: Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:405–413Google Scholar

5. Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD: Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:418–425Google Scholar

6. Twamley EW, Doshi RR, Nayak GV, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Jeste DV: Generalized cognitive impairments, ability to perform everyday tasks, and level of independence in community living situations of older patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2013–2020Google Scholar

7. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Kern RS, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, Keefe RS, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Marder SR: Functional co-primary measures for clinical trials in schizophrenia: results from the MATRICS Psychometric and Standardization Study. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:221–228Google Scholar

8. Leung WW, Bowie CR, Harvey PD: Functional implications of neuropsychological normality and symptom remission in older outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2008; 14:479–488Google Scholar

9. Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD: Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63:505–511Google Scholar

10. Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Swartz M, Stroup S, Lieberman JA, Keefe RSE: Relationship of cognition and psychopathology to functional impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:978–987Google Scholar

11. Pinkham AE, Penn DL: Neurocognitive and social cognitive predictors of interpersonal skill in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2006; 143:167–178Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, Stroup S, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J, CATIE Study Investigators Group: Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:411–417Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck RA, Frisman LK, Sindelar J: Disability compensation and work: a comparison of veterans with psychiatric and nonpsychiatric impairments. Pychiatr Serv 1995; 46:359–365Google Scholar

14. World Health Organization: International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Geneva, WHO, 1973Google Scholar

15. Harvey PD, Artiola i Fortuny L, Vester-Blockland E, De Smedt G: Cross-national cognitive assessment in schizophrenia clinical trials: a feasibility study. Schizophr Res 2003; 59:243–251Google Scholar

16. Harvey PD, Leff J, Trieman N, Anderson J, Davidson M: Cognitive impairment in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients: a cross-national study in New York and London. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:1001–1007Google Scholar

17. Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL: Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33:1364–1372Google Scholar

18. Schneider LC, Struening EL: SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr 1983; 19:9–21Google Scholar

19. Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S: The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH): an instrument for assessing psychopathology and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:615–623Google Scholar

20. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV: UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:235–245Google Scholar

21. Harvey PD, Keefe RS, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Bowie CR: Abbreviated neuropsychological assessment in schizophrenia: prediction of different aspects of outcome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2009; 31:462–471Google Scholar

22. Reitan RM, Wolfson D: The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation, 2nd ed. Tucson, Ariz, Neuropsychology Press, 1993Google Scholar

23. Spreen O, Strauss E: Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests and Norms, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

24. Heaton RK, Chellune CJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual, revised and expanded. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

25. Bellack AS, Green MF, Cook JA, Fenton W, Harvey PD, Heaton RK, Laughren T, Leon AC, Mayo DJ, Patrick DL, Patterson TL, Rose A, Stover E, Wykes T: Assessment of community functioning in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illness: a white paper based on an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33:805–822Google Scholar

26. Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS: Performance-based measures of functional skills: usefulness in clinical treatment studies. Schizophr Bull 2007; 33:1138–1148Google Scholar

27. Velligan DI, Diamond PM, Maples NJ, Mintz J, Li X, Glahn DC, Miller AL: Comparing the efficacy of interventions that use environmental supports to improve outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008; 102:312–319Google Scholar