Olanzapine in the Treatment of Low Body Weight and Obsessive Thinking in Women With Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

Objective: Anorexia nervosa is associated with high mortality, morbidity, and treatment costs. Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic, is known to result in weight gain in other patient populations. The objective of this trial was to assess the efficacy of olanzapine in promoting weight gain and in reducing obsessive symptoms among adult women with anorexia nervosa. Method: The study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 10-week flexible dose trial in which patients with anorexia nervosa (N=34) were randomly assigned to either olanzapine plus day hospital treatment or placebo plus day hospital treatment. Results: Compared with placebo, olanzapine resulted in a greater rate of increase in weight, earlier achievement of target body mass index, and a greater rate of decrease in obsessive symptoms. No differences in adverse effects were observed between the two treatment conditions. Conclusions: These preliminary results suggest that olanzapine may be safely used in achieving more rapid weight gain and improvement in obsessive symptoms among women with anorexia nervosa. Replication, in the form of a large multicenter trial, is recommended.

Anorexia nervosa is a serious debilitating illness that affects 0.5% of women ages 15–24 (1) . Anorexia nervosa is manifested as food restriction, a relentless pursuit of thinness caused by an obsessive fear of being fat, and a distorted body image of a delusional proportion that causes the patient to vehemently deny the seriousness of their obvious state of emaciation. The severe weight loss, associated medical complications, psychological morbidity, and chronic course of the illness result in anorexia nervosa having the highest mortality rate among all psychiatric disorders (2) .

Extended hospitalizations, which can restore weight to emaciated individuals, are expensive and discouraged by private medical insurance plans which are constantly pressuring for shorter lengths of inpatient stay (3 , 4) . Thus, patients with anorexia nervosa frequently are discharged as soon as medical stabilization is achieved, even though they are still underweight, a situation likely to cause them to fail in transitional day patient programs (5) . While few rigorous controlled trials have been conducted, it appears that pharmacological treatments, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (6 – 9) and standard neuroleptics (10 – 13) , as well as psychological treatments (14) administered during weight restoration, have not been predictably effective in increasing the rate of weight gain (thus shortening the length of hospital stay) or in reducing the psychological symptoms (particularly food obsessions) that perpetuate the patient’s resistance to weight restoration.

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic with a serotonin-dopamine antagonist profile and a reported side effect of weight gain. According to Tollefson et al. (15) , the side effect of weight gain is significantly more common among individuals with a low baseline body mass index. In addition to the desired weight gain effect, olanzapine may have some antiobsessive and antidepressant properties (16) . Such properties would be very beneficial to patients with the restricting subtype of anorexia nervosa, whose obsessional traits are often a contributing factor to their underlying psychopathology (17) . The antidepressant properties of olanzapine would be equally beneficial to those patients with the binge/purge subtype, whose binging and purging behavior is often a coping mechanism to relieve dysphoric mood and psychic tension (17) .

Over the last few years, evidence supporting the use of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa has accumulated (reviewed in reference 18 ). Olanzapine has been reported in 22 case reports, two retrospective studies (18) , and two open trials (19 , 20) to be clinically beneficial in anorexia nervosa in terms of facilitating weight gain and reducing the obsessive pursuit of thinness and associated anxiety observed in these patients. Little of the literature, however, is based on clinical trials, which led La Via et al. (21) to recommend a controlled trial to demonstrate the efficacy of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa. A randomized, controlled trial of olanzapine versus chlorpromazine was conducted (22) ; however, the treatment arms were not blinded. Although the two treatment conditions did not differ in weight gain, patients receiving olanzapine experienced a reduction in anorexic rumination (22) . Recently, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa (23) was conducted using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), an analytic approach to longitudinal data with known disadvantages (24) . No statistically significant difference in weight gain between the treatment and placebo conditions was found. When the sample was stratified by anorexia nervosa subtype, however, the increase in body mass index was significantly greater among those participants with the binge/purge subtype of anorexia nervosa receiving olanzapine. Olanzapine demonstrated significant improvements in depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsiveness, and aggressiveness compared with placebo. Taken as a whole, the literature suggests that olanzapine has positive effects on psychological symptoms associated with anorexia nervosa, but its effect on weight gain remains unclear.

The present study was designed to evaluate the effect of olanzapine on weight gain in patients with anorexia nervosa. A secondary objective was to evaluate the antiobsessive, anticompulsive, antianxiety, and antidepressant properties of the medication, which would be beneficial in improving treatment outcomes for patients with anorexia nervosa. This 10-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa involved patients attending an intensive day hospital program for eating disorders 4 days per week. We hypothesized that olanzapine plus participation in the day hospital program would result in 1) a greater rate of weight gain, 2) a shorter time to achievement of a healthy target weight, and 3) a greater positive change in depression, anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions compared with placebo.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants were recruited from patients referred to the eating disorders program at The Ottawa Hospital by a family physician or psychiatrist between September 2000 and April 2006. All participants met DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa (restricting or binge/purge subtype), including a body mass index ≤17.5 kg/m 2 . Secondary amenorrhea, however, was not required. Exclusion criteria were active suicidal intent, comorbid substance abuse disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or any other psychotic disorder, organic brain syndromes or dissociative disorders, pregnancy, and failure to use effective contraception if sexually active. Participants were required to remain free from psychotropic medication for a 2-week period prior to beginning the study medication. Of the 147 patients who were approached, 34 met criteria, agreed to participate, and were enrolled in the trial.

Inclusion criteria required all participants to attend the day hospital program for eating disorders. This program is publicly funded and exists within the department of psychiatry of The Ottawa Hospital. The program is modeled on the Toronto General Hospital’s eating disorders program (25) and shares a number of features with other day hospitals, including supervised meals and group therapy (26) . The program accommodates up to eight patients with moderate to severe eating disorder pathology. Patients attend the program 4 days a week, from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., for 12 to 14 weeks. In a naturalistic study with a separate sample of women with anorexia nervosa, this program demonstrated positive outcomes for weight restoration and in eating disorder attitudes and behaviors, depression, and interpersonal problems (27) .

After complete description of the study to participants, written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment in the trial. The study was approved by the hospital research ethics board and registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

Measures

Body weight and height were assessed on a calibrated balance beam scale (Health-o-meter 402KL, Alsip, Ill.). Height was measured at the beginning of the study. Body mass index was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared.

Anxiety and depression were measured using the full scales of the Personality Assessment Inventory (28) , a self-report measure. Each scale has 24 items that assess anxiety and depression in terms of cognitive, affective, and physiological domains. Scale scores were transformed into T scores based on a normative population mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with higher scores representing greater depression or anxiety. These scales have been shown to have excellent psychometric properties in an eating disorder population (29) .

Obsessions and compulsions were rated by a clinician using the 10-item Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (30) . This scale provides a measure of the severity of symptoms of general obsessions and compulsions that is not influenced by the type of obsessions or compulsions. Five items each are summed for the obsessions and compulsions scales, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms. These scales have excellent psychometric properties (30) , and the measure differentiates eating disorder groups from a normative population (31) . Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale assessments were conducted by two clinicians who initially rated the patients separately and then came to a consensus when ratings differed.

Procedure

No clinical trial of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa had been published when the present study began; therefore, the work of Tollefson and colleagues (16) on olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia was used to estimate the number of participants required. Based on their results, a large effect size (d=1) was expected. For adequate power (0.80) and with alpha set at 0.05 (one-tailed), it was estimated that a total of 28 participants were required.

Potential participants received a diagnostic interview conducted by two independent clinicians, a psychiatrist and a psychologist. Agreement between the two assessors was required for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. To further assess the accuracy of diagnosis, written reports, with diagnostic conclusions and patient-identifying data removed, were reviewed by a blind expert. There was 100% agreement between the blind assessment and the original diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, including 100% agreement on subtype.

Patients who met inclusion criteria and agreed to participate were randomly assigned to either the olanzapine plus day hospital condition or placebo plus day hospital condition. Randomization was stratified according to anorexia nervosa subtype (restricting or binge/purge). Stratified block randomization was completed by an independent statistician using a computer random number generator. A card indicating group assignment was prepared for each successive participant and placed in a sealed opaque envelope with the stratum identified on the outside. An independent hospital pharmacist retained these envelopes unopened and in sequence until provided with the identity and anorexia nervosa subtype of each new participant. All study personnel and participants were blind to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. Only the pharmacist was aware of group assignment. A log was kept in case of a medical emergency that required the treatment team to be unblinded, but it was not used. Medication was delivered from the pharmacy to the day hospital program and dispensed by the psychiatrist responsible for patient care, who was also blind to group assignment. The olanzapine and placebo tablets were indistinguishable in appearance to both participants and study personnel.

The duration of the study was 13 weeks. After a 2-week baseline period, olanzapine or placebo was administered for 10 weeks (weeks 3–12 of the study). Olanzapine was prescribed according to a flexible dose regimen, starting at the minimum dose of 2.5 mg/day and titrated slowly by increments of 2.5 mg/week to a maximum dose of 10 mg/day. Weight was measured once a week for 13 weeks. Assessment of psychological variables (depression, anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions) occurred during the first baseline week (week 1) and posttreatment (week 13).

Statistical Analyses

Hierarchical linear modeling (32) , which is a mixed-effects random regression approach, was used to model growth curve change trajectories for each patient’s body mass index across the 13 weeks of the trial while controlling for anorexia nervosa subtype. Growth curves allow for the assessment of the differential rate or rapidity of increase in body mass index across treatment conditions. Hierarchical linear growth models (mixed-effects models) for weekly body mass index and random blood glucose level measurements were as follows:

Level 1: Y =π 0 + π 1 (weeks) + e

Level 2: π 0 =β 00 + β 01 (condition) + β 02 (pretreatment score) + β 03 (subtype) + u0 and π 1 =β 10 + β 11 (condition) + β 12 (pretreatment score) + β 13 (subtype) + u1

where Y refers to body mass index across patient and time, β 10 is the average growth parameter across weeks and patients, and β 11 (condition) refers to the difference in growth parameters between treatment conditions.

Outcomes on psychological variables (depression, anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions) were also assessed using mixed-effects growth models, but with random intercepts and fixed slopes, while controlling for the respective pretreatment levels and for anorexia nervosa subtype. Mixed-effects models to assess pre- to posttreatment change in psychological variables were as follows:

Level 1: Y =π 0 + π 1 (time) + e

Level 2: π 0 =β 00 + β 01 (condition) + β 02 (pretreatment score) + β 03 (subtype) + u0 and π 1 =β 10 + β 11 (condition) + β 12 (pretreatment) + β 13 (subtype)

where Y refers to the psychological variable across patient and time (pre- to posttreatment), β 10 is the average growth parameter for patients, and β 11 (condition) refers to the difference in growth parameters between treatment conditions.

Growth curve modeling is the preferred method of assessing longitudinal or repeated measurement data (24 , 33) because it avoids the restrictive assumptions of repeated measures ANOVA, and one can make use of all available data without either imputation of missing data or listwise deletion of data (34) . This avoids parameter biases inherent in last observation carried forward methods (35) .

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed to compare study conditions in mean time to achievement of weight restoration (defined as a body mass index ≥18.5 kg/m 2 ). A survival analysis was conducted on all participant data, with right censoring applied to data of those individuals who withdrew from the study. The analysis controlled for anorexia nervosa subtype. Chi-square tests were conducted to compare the percentage of patients in each condition who dropped out of treatment.

Results

All data were normally distributed, and there was no evidence of univariate or multivariate outliers at any of the time points. Type I error rates were set at p<0.05 per test. Although one-tailed tests were conducted, a similar pattern of results was obtained with two-tailed tests. Hence, only the two-tailed tests are reported.

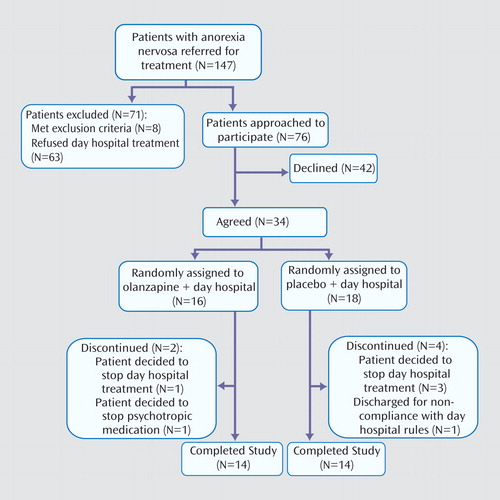

Treatment Implementation and Subject Characterization

During the data collection period, 147 female patients meeting criteria for anorexia nervosa were referred for treatment ( Figure 1 ). Of these, 71 patients were excluded: eight patients met one or more exclusion criteria and 63 otherwise eligible patients refused treatment in the day hospital program. Reasons for refusing to participate in the program included conflict with school or work schedules, prohibitive geographic location (i.e., too far to travel), and refusal to agree to intensive treatment. Of the remaining 76 eligible patients, 34 agreed to participate and 42 declined. Of the 34 patients enrolled in the study, 16 were randomly assigned to the olanzapine plus day hospital condition and 18 were randomly assigned to the placebo plus day hospital condition. Two women dropped out of the olanzapine plus day hospital condition: one patient was not ready for treatment and left the day hospital program, and the second patient subsequently expressed an unwillingness to take any psychotropic medication. Four patients dropped out of the placebo plus day hospital condition: three left because they were not ready for treatment, and the other was asked to leave because of continued substance use, which was against program rules. The proportion of drop-outs was similar across conditions (χ 2 =0.09, df=1, p=0.77).

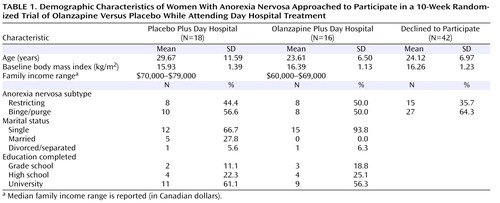

Demographic characteristics at baseline for the two treatment conditions and of those patients who declined to participate are presented in Table 1 . Patients enrolled in the study were similar to eligible individuals who declined to participate (N=42) in both age (F=2.25, df=1, 74, p=0.14) and body mass index (F=0.18, df=1, 74, p=0.67). The proportion of patients within each subtype of anorexia nervosa was also similar across patients enrolled in the study and those who declined to participate (χ 2 =1.00, df=1, p=0.32).

The mean dose of olanzapine over the 10-week treatment period for study completers (N=14) was 6.61 mg/day (SD=2.32).

Treatment Adherence

To monitor treatment adherence, weekly urine samples were collected and analyzed at an independent laboratory. Urine samples were screened by automated high pressure liquid chromatography using a system for broad spectrum drug screening (Bio-Rad REMEDi HS, Hercules, Calif.). The method detects olanzapine and its principle metabolites, N -desmethyl olanzapine and 2-hydroxymethyl olanzapine. Laboratory results indicated that all participants were compliant throughout the trial.

Adverse Effects

There were no serious adverse side effects (e.g., extrapyramidal symptoms, excessive sleepiness, dizziness, or galactorrhea) reported or found during weekly medical examinations. Blood glucose levels were randomly tested each week in all patients. There was no evidence of impaired glucose tolerance or de novo development of diabetes mellitus in any participant. Mixed-model regression growth curves indicated no difference between conditions in overall blood glucose levels (β 00 = –0.20; t=1.18, df=32, p=0.25) and no difference in the rate of change in blood glucose levels across weeks (β 10 = –0.03; t=1.22, df=32, p=0.23).

Weight Gain

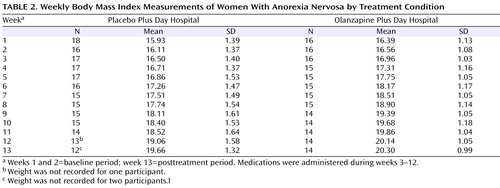

Mean body mass index measurements per week are presented in Table 2 . As suggested by Singer and Willett (33) , individual empirical growth plots were examined visually, and these indicated that a linear model would best represent the data. Furthermore, 95% of the within-subject growth variance was accounted for by a linear model. Growth curve change trajectories indicated that all patients, including those receiving placebo and those receiving olanzapine, showed significant increases in body mass index across the 13 weeks of the trial (β 10 =0.29; t=7.44, df=32, p<0.001). However, patients receiving olanzapine showed a greater rate of increase in body mass index across weeks compared with patients receiving placebo (β 11 = –0.06; t= –2.25, df=31, p=0.03).

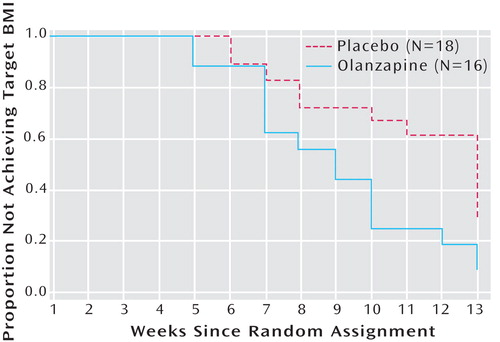

Survival analysis comparing treatment conditions in time to achievement of target body mass index (18.5 kg/m 2 ) was conducted. Of the total sample, 55.6% of patients receiving placebo and 87.5% of patients receiving olanzapine achieved weight restoration (Mantel-Cox test: χ 2 =5.42, df=1, p=0.02). For the olanzapine group, the mean survival time was 8.06 weeks (SE=0.68, 96% CI=6.74–9.39). For the placebo group, the mean survival time was 10.06 weeks (SE=0.67, 95% CI=8.75–11.36) ( Figure 2 ).

a Kaplan-Meier survival curves analysis indicated a significant difference between groups (Mantel-Cox test: χ 2 =5.31, df=1, p=0.02).

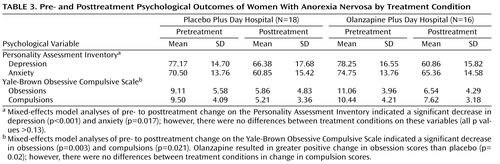

Psychological Symptoms Associated With Anorexia

Psychological outcomes according to treatment condition, both pre- and posttreatment, are presented in Table 3 . Mixed-effects model analyses of pre- to posttreatment change on the Personality Assessment Inventory indicated a significant decrease in depression (β 10 = –15.79; t=4.23, df=57, p<0.001) and anxiety (β 10 = –6.96; t=2.46, df=57, p=0.02) across both treatment conditions. However, comparison of the two conditions showed no differences in change in depression scores (β 11 =8.28; t=1.52, df=55, p=0.13) or anxiety scores (β 11 =2.82; t=0.60, df=55, p=0.55). Mixed-effects model analyses of pre- to posttreatment change on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale indicated a significant decrease in obsessions (β 10 = –4.25; t=3.20, df=57, p=0.003) and compulsions (β 10 = –3.36; t=3.79, df=57, p=0.001) across both treatment conditions. Comparison of the two conditions indicated that olanzapine resulted in greater positive change in obsession scores than placebo (β 11 =4.20; t=2.37, df=55, p=0.02). No differences in change in compulsion scores were evident between conditions (β 11 =0.60; t=0.45, df=55, p=0.70).

Discussion

The results provide preliminary evidence to address the inconsistency in the literature concerning the effects of olanzapine on weight gain in anorexia nervosa. By using modern analytic techniques for repeated measurement data (i.e., hierarchical linear modeling and survival analysis), we demonstrated that treatment with olanzapine resulted in greater and more rapid weight gain than placebo in a sample of patients with anorexia nervosa attending a day hospital treatment program for eating disorders. Furthermore, the robustness of this conclusion is supported by the similarity in the results from the two different analytic approaches to the data, i.e., hierarchical linear modeling and survival analysis. This suggests that olanzapine was helpful to patients in achieving target body mass index more quickly. This bodes well for patients requiring more comprehensive treatment for anorexia nervosa, because researchers have found that early response to treatment is a predictor of positive outcomes in individuals with an eating disorder (36) . Earlier response to treatment may also help to reduce the length of stay for expensive inpatient treatments for anorexia nervosa.

Both the placebo plus day hospital and olanzapine plus day hospital conditions resulted in improvements in depression, anxiety, and obsessive and compulsive symptoms over the period of this trial. This is similar to results reported in a previous study with a different sample demonstrating the effectiveness of day hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa (27) . Hence, a sizable amount of change in psychological symptoms was likely attributable to day hospital treatment alone. In addition, there was promising evidence of additional treatment effects of olanzapine for obsessive symptoms. This suggests that the suspected antiobsessive properties of olanzapine may confer added benefit to women with anorexia nervosa, whose obsessional traits may be debilitating and a hindrance to positive outcomes (17) .

Some researchers and clinicians have expressed concern that atypical antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, may increase the risk of developing diabetes mellitus, particularly type II diabetes (37 – 39) . However, this concern is primarily related to the long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia, who have a high prevalence of obesity and related medical disorders (38 , 40) . No serious side effects or adverse medical effects, such as impaired glucose tolerance or de novo diabetes mellitus, were noted in the present study.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, because this is a clinical trial of a pharmacological treatment, it is required that olanzapine demonstrate effects over and above an already effective psychological treatment. This potential constraint on the effect size of olanzapine may have reduced the power of the analyses. Conversely, there is the possibility that psychological treatment may have enhanced compliance with the olanzapine treatment. The impact of psychological treatment on the effect size of olanzapine treatment is unknown. Second, the power of the analyses was already modest given the small sample size. Thus, some potentially clinically meaningful differences may have failed to reach statistical significance. However, as demonstrated by the number of patients refusing treatment during this trial, recruiting a large sample of willing patients with anorexia nervosa is a challenge that has long impeded treatment research with this population. Likely, this issue will necessitate a large multicenter trial. Although these results may be considered preliminary and require replication, the present study remains one of the largest of its kind. Third, over half of the patients approached for this study refused to participate. This reduces the generalizability of the results to patients with anorexia nervosa who are willing to accept pharmacological and intensive day treatments in order to enhance weight gain. A fourth limitation is that there is no follow-up data. The provision of olanzapine was viewed as a time-limited enhancement to current treatment. The lack of follow-up limits what can be said about the long-term impact of olanzapine on weight gain and obsessive symptoms.

The results of the present study suggest that olanzapine is likely useful in increasing the rate of weight gain and in reducing time to achievement of weight restoration among patients with anorexia nervosa. There was also evidence of the potential for olanzapine to reduce obsessive symptoms among patients with anorexia nervosa. The variance outcomes from this study may be useful in providing sample size estimates for future trials. Furthermore, the results clearly demonstrate the value in undertaking future randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies of longer duration and with follow-up and a larger population to more definitively assess the effectiveness and safety of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

1. Hsu LK: Epidemiology of the eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:681–700Google Scholar

2. Sullivan PF: Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1073–1074Google Scholar

3. Treat TA, Gaskill JA, McCabe EB, Ghinassi FA, Luczak AD, Marcus MD: Short-term outcome of psychiatric inpatients in the current care environment. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 38:123–133Google Scholar

4. Andersen AE: Treatment of eating disorders in the context of managed health care in the United States: a clinician’s perspective, in Treating Eating Disorders: Ethical, Legal, and Personal Issues. Edited by Vandereycken W, Beumont PJ. New York, New York University Press, 1998, pp 261–282Google Scholar

5. Howard WT, Evans KK, Quintero-Howard CV, Bowers WA, Andersen AE: Predictors of success or failure of transition to day hospital treatment for inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1697–1702Google Scholar

6. Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR: Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:548–551Google Scholar

7. Ferguson CP, La Via MC, Crossan PJ, Kaye WH: Are serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors effective in underweight anorexia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord 1999; 25:11–17Google Scholar

8. Peterson CB, Mitchell JE: Psychosocial and pharmacological treatment of eating disorders: a review of research findings. J Clin Psychol 1999; 55:685–697Google Scholar

9. Strober M, Pataki C, Freeman R, DeAntonio M: No effect of adjunctive fluoxetine on eating behavior or weight phobia during the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: an historical case-control study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999; 9:195–201Google Scholar

10. Dally PJ, Sargant W: A new treatment of anorexia nervosa. Br Med J 1960; 1:1770–1773Google Scholar

11. Dally P, Sargant W: Treatment and outcome of anorexia nervosa. Br Med J 1966; 2:793–795Google Scholar

12. Vandereycken W, Pierloot R: Pimozide combined with behaviour therapy in the short-term treatment of anorexia nervosa: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982; 66:445–450Google Scholar

13. Vandereycken W: Neuroleptics in the short-term treatment of anorexia nervosa: a double-blind placebo-controlled study with sulpiride. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144:288–292Google Scholar

14. Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM: Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol 2007; 62:199–216Google Scholar

15. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, Graffeo KA, Thieme ME: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:457–465Google Scholar

16. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Lu Y, Thieme ME: Depressive signs and symptoms in schizophrenia: a prospective blinded trial of olanzapine and haloperidol. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:250–258Google Scholar

17. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE: Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

18. Dunican KC, DelDotto D: The role of olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41:111–115Google Scholar

19. Powers PS, Santana CA, Bannon YS: Olanzapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: an open label trial. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 32:146–154Google Scholar

20. Barbarich NC, McConaha CW, Gaskill J, La Via M, Frank GK, Achenbach S, Plotnicov KH, Kaye WH: An open trial of olanzapine in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1480–1482Google Scholar

21. La Via MC, Gray N, Kaye WH: Case reports of olanzapine treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2000; 27:363–366Google Scholar

22. Mondraty N, Birmingham CL, Touyz S, Sundakov V, Chapman L, Beumont P: Randomized controlled trial of olanzapine in the treatment of cognitions in anorexia nervosa. Australas Psychiatry 2005; 13:72–75Google Scholar

23. Brambilla F, Garcia CS, Fassino S, Daga GA, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Ramaciotti C, Bondi E, Mellado C, Borriello R, Monteleone P: Olanzapine therapy in anorexia nervosa: psychobiological effects. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22:197–204Google Scholar

24. Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH: Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:310–317Google Scholar

25. Olmsted MP, McFarlane T, Molleken L, Kaplan AS: Day hospital treatment for eating disorders, in Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001Google Scholar

26. Zipfel S, Reas DL, Thornton C, Olmsted MP, Williamson DA, Gerlinghoff M, Herzog W, Beumont PJ: Day hospitalization programs for eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 2002; 31:105–117Google Scholar

27. Tasca GA, Taylor D, Bissada H, Ritchie K, Balfour L: Attachment predicts treatment completion in an eating disorders partial hospital program among women with anorexia nervosa. J Pers Assess 2004; 83:201–212Google Scholar

28. Morey LC: Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI): Professional Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991Google Scholar

29. Tasca GA, Wood J, Demidenko N, Bissada H: Using the PAI with an eating disordered population: scale characteristics, factor structure, and differences among diagnostic groups. J Pers Assess 2002; 79:337–356Google Scholar

30. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

31. Speranza M, Corcos M, Godart N, Loas G, Guilbaud O, Jeammet P, Flament M: Obsessive compulsive disorders in eating disorders. Eat Behav 2001; 2:193–207Google Scholar

32. Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS: Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 2002Google Scholar

33. Singer JD, Willet JB: Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

34. Hox J: Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002Google Scholar

35. Simpson HB, Petkova E, Cheng J, Huppert J, Foa E, Liebowitz MR: Statistical choices can affect inferences about treatment efficacy: a case study from obsessive-compulsive disorder research. J Psychiatr Res 2007 (Epub ahead of print)Google Scholar

36. Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E: Prediction of outcome in bulimia nervosa by early change in treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2322–2324Google Scholar

37. Zoler ML: Antipsychotics linked to weight gain, diabetes. Clin Psychiatry News 1999; 27:20Google Scholar

38. McIntyre RS, McCann SM, Kennedy SH: Antipsychotic metabolic effects: weight gain, diabetes mellitus, and lipid abnormalities. Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46:273–281Google Scholar

39. Tschoner A, Engl J, Laimer M, Kaser S, Rettenbacher M, Fleischhacker WW, Patsch JR, Ebenbichler CF: Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61:1356–1370Google Scholar

40. Canadian Diabetes Association: 2003 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes 2003; 27(suppl 2):S1–S140Google Scholar