Compulsive Hoarding: OCD Symptom, Distinct Clinical Syndrome, or Both?

Abstract

Objective: Compulsive hoarding is a debilitating problem that is often associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. However, the precise nosology of compulsive hoarding has yet to be determined. Method: Participants were 25 patients with severe compulsive hoarding with OCD and 27 patients with severe compulsive hoarding without OCD. Both groups were carefully characterized and compared on the following sociodemographic and clinical variables: precise phenomenology of hoarding behavior, severity of other OCD symptoms, axis I and axis II psychopathology, and adaptive functioning. For comparison purposes, the following individuals were also recruited: 71 patients with OCD without hoarding, 19 patients with anxiety disorder, and 21 community participants. Results: Overall, the phenomenology of hoarding behavior was similar in the two hoarding groups. The majority of participants in both groups reported hoarding common items as a result of their emotional and/or intrinsic value. However, approximately one-fourth of participants in the compulsive hoarding with OCD group showed a different psychopathological profile, which was characterized by the hoarding of bizarre items and the presence of other obsessions and compulsions related to their hoarding, such as fear of catastrophic consequences, the need to perform checking rituals, and the need to perform mental compulsions before discarding any item. These patients had a more severe and disabling form of the disorder. The strong relationship between compulsive hoarding and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was explained entirely by the overlapping item content. Conclusions: In most individuals, compulsive hoarding appears to be a syndrome separate from OCD, which is associated with substantial levels of disability and social isolation. However, in other individuals, compulsive hoarding may be considered a symptom of OCD and has unique clinical features. These findings have implications for the classification of OCD and compulsive hoarding in the next edition of DSM.

Compulsive hoarding is a problem that is characterized by excessive collecting and the failure to discard excessive amounts of collected items, in addition to the cluttering of living space and significant distress or impairment caused by the hoarding (1) . Compulsive hoarding is a relatively common symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Between 15% and 40% of OCD patients endorse hoarding and saving compulsions (2 – 4) , although these symptoms may only be disabling in approximately 5% of these individuals (5) . In OCD, the presence of hoarding symptoms has been associated with 1) increased axis I and axis II comorbidity, 2) impairment in the performance of activities of daily living, 3) reduced insight, 4) poor response to standard psychological and pharmacological treatments, and 5) a distinct genetic and neurobiological profile, all of which suggest that compulsive hoarding may be an etiologically distinct variant of OCD (6 – 9) . It is also possible that compulsive hoarding is a separate syndrome—which some have termed compulsive hoarding syndrome (8) —that can be comorbid with OCD. The latter hypothesis is supported by the fact that hoarding often presents in other psychiatric disorders and even in the absence of any major psychopathology (7) . To further add to the complexity, hoarding is also listed as one of the eight DSM-IV criteria for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

To date, studies of individuals with compulsive hoarding have utilized several methods. Some investigators chose to examine subgroups of OCD patients who endorsed hoarding symptoms on the symptom checklist of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (10) , or they selected an arbitrary cutoff on other self-administered measures of compulsive hoarding. Other investigators chose to adopt a more dimensional approach by correlating the severity of hoarding symptoms with the dependent variables of their study. Although these studies compared OCD patients with and without hoarding symptoms, they tended to include patients with mild or moderate symptoms, thus making it difficult to generalize the results to patients with more severe symptoms. Other studies utilized a method that involved the selection of individuals with severe hoarding symptoms, regardless of their main axis I diagnoses (11 , 12) . While these studies included individuals with severe symptoms, they did not directly compare compulsive hoarding with and without OCD. Thus, the nosology of compulsive hoarding remains unclear.

The objective of the present case control study was to shed light on this important nosological question by systematically comparing individuals with severe compulsive hoarding who met DSM-IV criteria for OCD (OCD plus hoarding group) with individuals with severe hoarding who did not meet criteria for OCD (hoarding minus OCD group). Both hoarding groups were compared on a variety of sociodemographic and psychopathological variables. For comparison, we also recruited 1) samples of OCD patients without hoarding symptoms (OCD minus hoarding group), 2) individuals with anxiety disorder, and 3) community participants. We hypothesized that the features of compulsive hoarding in the context of OCD would be comparable with those of compulsive hoarding without OCD.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The 163 individuals recruited to participate in the study were as follows: 27 patients in the hoarding minus OCD group, 25 patients in the OCD plus hoarding group, 71 comparison patients in the OCD minus hoarding group, 19 comparison patients with anxiety disorder, and 21 community comparison subjects. Participants were recruited between September 2005 and July 2007 via OCD or anxiety clinics, advertisements in patient organization newsletters or websites, support groups, and a conference on compulsive hoarding held in London, November 2005. The majority of participants (>90%) in both hoarding groups as well as in the anxiety disorder comparison group were recruited via advertisement and support groups, whereas most individuals (60%) in the OCD minus hoarding group were recruited via clinical settings.

All participants, including comparison subjects, were interviewed either face-to-face or via telephone by clinical psychiatrists or psychologists with experience in OCD, using validated-structured interviews. Participants were excluded if they were <18 years of age; were >65 years of age; or met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, psychosis, suicidality, or substance abuse or dependence. Written informed consent was obtained, and participants were compensated for their time. The study was approved by the Institute of Psychiatry/Maudsley Hospital Ethics Committee, London.

A sample of individuals with severe compulsive hoarding, regardless of psychiatric diagnoses or comorbidities, was initially recruited. Symptoms of compulsive hoarding were strictly defined using the following five criteria according to Frost and Hartl (1) , Steketee and Frost (7) , and Grisham et al. (12) : 1) acquisition of and failure to discard a large number of possessions; 2) a living space sufficiently cluttered in a manner that precludes activities for which the space was designed; 3) significant distress or impairment in functioning caused by hoarding; 4) clutter persisting at least 6 months; and 5) hoarding behavior not caused by other mental disorders (e.g., dementia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder). In addition, individuals classified as having severe compulsive hoarding were required to have a score of ≥40 on the Saving Inventory–Revised (13) . This method ensured that only patients with significant and disabling hoarding symptoms would be included in the study.

Participants who fulfilled these criteria were then further divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of a diagnosis of OCD according to DSM-IV criteria. Individuals with compulsive hoarding were only diagnosed as having OCD if they endorsed other prototypical OCD symptoms or if they had obsessions or compulsions as defined in DSM-IV (e.g., intrusive thoughts, anxiety-provoking images or impulses, repetitive behaviors, or mental acts compelling the individual to perform in response to an obsession). The two groups were identified as OCD plus hoarding and hoarding minus OCD, respectively.

Seven respondents who defined themselves as “pack rats” were excluded because they did not meet criteria for compulsive hoarding. Five respondents who met strict criteria for compulsive hoarding were excluded because they also met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder (N=2), psychosis (N=1), suicidal ideation (N=1), or a suspected dementing process (N=1).

Measures

Clinician-administered

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (14 – 16) was administered in order to identify the presence of major DSM-IV axis I diagnoses.

The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–4+ (17 , 18) was used to assess the presence of DSM-IV axis II personality disorders. Participants who endorsed sufficient items on the self-report to suggest a possible personality disorder were interviewed by a clinician in order to reduce the number of false-positive diagnoses.

The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (19) consists of an 88-item self-report checklist of obsessions and compulsions, which are divided into six dimensions (contamination/cleaning, harm, collecting/hoarding, symmetry/ordering, sexual/religious, and miscellaneous obsessions and compulsions), and a series of clinician-administered scales that can be used to assess the presence and severity of each symptom dimension. In its original validation study, the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale proved to be reliable and showed good construct and divergent validity in both child and adult samples.

A semistructured, clinician-administered hoarding interview was developed for the present study, which was partially based on an earlier assessment tool by Seedat and Stein (20) . This instrument contains detailed questions pertaining to 1) specific items being hoarded, 2) extent of clutter, 3) reasons for hoarding, 4) degree of distress and impairment caused by hoarding, 4) age at onset of hoarding, 5) family history of hoarding behavior, 6) living situation, and 7) marital status.

Self-administered

Hoarding and obsessive-compulsive symptoms were self-assessed using the Saving Inventory–Revised (13 , 21) and the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised (22 , 23) , respectively. Depressive symptoms were rated using the Beck Depression Inventory (24 , 25) , and impairment in various areas of daily functioning was assessed using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (26 , 27) .

Data Analyses

Categorical data were compared using chi square or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous independent data were compared using Student’s t tests or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey B (in cases of equal variances) or Tamhane’s T2 (in cases of unequal variances) post hoc tests. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were used to control for possible confounders (e.g., sex, age) when distribution across groups varied significantly. All statistical tests were two-tailed at p<0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic Variables

Since there were no differences between English-speaking (N=122) and Spanish-speaking (N=41) participants on any sociodemographic and clinical variables, data for these two groups were pooled for analysis. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in age between the five study groups (F=12.876, df=4, 158, p<0.0001 [ Table 1 ]). Post hoc tests revealed that individuals in the hoarding minus OCD and OCD plus hoarding groups were significantly older than individuals in the OCD minus hoarding and anxiety disorder comparison groups. The proportion of women was greater in the two hoarding groups relative to the OCD minus hoarding comparison group. However, since ANCOVAs for age and sex were controlled (dummy-coded 1 to 2) and did not modify the overall results, these variables were not considered further. The study groups did not differ with regard to education level or ethnic composition. Participants in the two hoarding groups were more likely to live alone compared with individuals in the three comparison groups. Participants in the OCD plus hoarding group were less likely to be married than individuals in the other four groups.

Family History of OCD and Compulsive Hoarding

A greater number of participants in the OCD plus hoarding group (40.0%) reported having at least one relative affected with OCD compared with the number of participants in the hoarding minus OCD group (25.9%) and OCD minus hoarding comparison group (21.0%). However, this difference was not statistically significant. Participants in these three groups were more likely to have a relative with OCD compared with individuals in the anxiety disorder and community comparison groups (all p values <0.01). However, the two hoarding groups reported a greater family history of hoarding relative to the OCD minus hoarding (χ 2 =13.6, df=2, p=0.001), anxiety disorder, and community comparison groups (all p values <0.001) ( Table 1 ).

Phenomenology of Hoarding Behavior

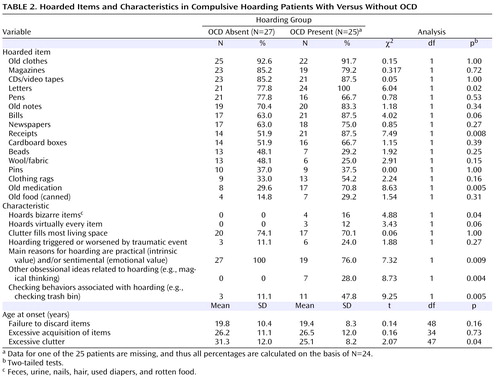

Both hoarding groups reported accumulating similar kinds of objects, with the exception of letters, receipts, bills, and old medication, which were more frequently hoarded by individuals in the OCD plus hoarding group ( Table 2 ). None of the participants reported significant animal hoarding. Participants in the OCD plus hoarding group were more likely to hoard bizarre items (N=4 [14%]) relative to individuals in the hoarding minus OCD group (N=0). Three (12%) participants in the OCD plus hoarding group and none of the individuals in the hoarding minus OCD group reported their hoarding behavior as extremely pervasive (i.e., the need to save/hoard virtually every item). However, there were no overall differences in the degree of clutter accumulated between the two hoarding groups. (In the hoarding minus OCD group, 74.1% of participants reported that clutter filled most of the living space in their homes compared with 70.1% of individuals in the hoarding plus OCD group.)

The number of individuals who reported that their hoarding behavior started or worsened after a traumatic event (e.g., possessions lost after a fire) was similar in the two hoarding groups ( Table 2 ). Participants in both groups reported that they started experiencing significant difficulties discarding items at a similar age (19.6 years [SD=9.4]), although the homes of participants in the OCD plus hoarding group became cluttered at an earlier age relative to the homes of individuals in the hoarding minus OCD group (25.1 years [SD=8.2] versus 31.3 years [SD=12.0], respectively). None of the participants in the hoarding minus OCD group reported hoarding as a result of reasons other than the intrinsic (i.e., items are valuable or may come in handy in the future) and/or emotional (i.e., sentimental attachment to possessions) value of the hoarded items. In contrast, approximately one-fourth of participants in the OCD plus hoarding group reported other obsessions or compulsions related to their hoarding, such as a fear of catastrophic consequences (e.g., something bad will happen if things get thrown away), a need to check that important or valuable items are not discarded, a need to discard items in certain “lucky” numbers, or a need to perform mental compulsions when discarding any item.

Severity of Hoarding Symptoms

As expected, the two hoarding groups had significantly higher scores relative to the three comparison groups on clinician (Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale) and self-rated (Saving Inventory–Revised, Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised) measures of hoarding severity (see the table in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). The OCD plus hoarding group tended to have significantly higher hoarding severity relative to the hoarding minus OCD group on all measures. However, this difference only reached statistical significance on the clinician-administered hoarding dimension subscale of the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Individuals in the OCD minus hoarding comparison group had hoarding scores that were comparable with scores of individuals in the anxiety disorder and community comparison groups (Saving Inventory–Revised and Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised).

Severity of Other OCD Symptom Dimensions

As expected, the hoarding minus OCD group had significantly lower scores relative to the two OCD groups (OCD plus hoarding and OCD minus hoarding) on all other OCD symptom dimensions, both clinician and self-rated. Individuals in the hoarding minus OCD group and anxiety disorder and community comparison groups had comparable scores on all symptom dimensions (see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). The OCD plus hoarding group scored higher on the symmetry dimension of the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale relative to the OCD minus hoarding comparison group, but not on the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised.

Regarding global OCD severity, the hoarding minus OCD group scored significantly lower than the two OCD groups on all global severity measures. This was the case even after removing the hoarding items from the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale global severity score (see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article).

Axis I and Axis II Disorders

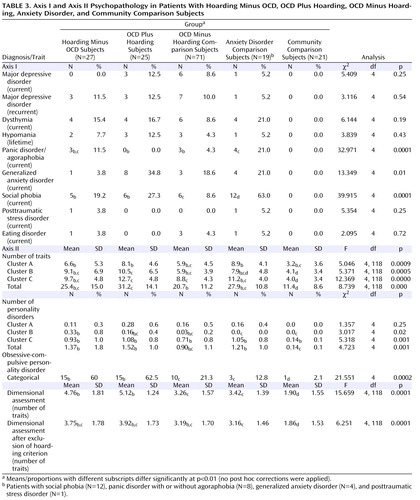

Participants in the two OCD groups were significantly more likely to have comorbid generalized anxiety disorder compared with participants in the hoarding minus OCD group (χ 2 =7.75, df=2, p=0.02). Social phobia was more prevalent in the two hoarding groups compared with the OCD minus hoarding comparison group (χ 2 =6.41, df=2, p=0.04).

Regarding the number of personality disorder traits ( Table 3 ), participants in the two hoarding groups endorsed a significantly higher number of cluster B personality traits compared with participants in the OCD minus hoarding comparison group (F=4.59, df=2, 118, p=0.01), and the OCD plus hoarding group endorsed more cluster C personality traits than the OCD minus hoarding and hoarding minus OCD groups (F=5.06, df=2, 118, p=0.008). Although obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (assessed both categorically and dimensionally) was more prevalent in the two hoarding groups relative to the three comparison groups, after the exclusion of the hoarding/collecting criterion, the number of endorsed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder criteria was comparable in the four patient groups (hoarding minus OCD, OCD plus hoarding, OCD minus hoarding, and anxiety disorder [ Table 3 ]).

Daily Functioning/Adjustment and Depressive Symptoms

All four patient groups had significantly higher levels of reported depression (Beck Depression Inventory) as well as higher levels of work disability and impaired social/leisure activities and family/friend relationships relative to community comparison participants (all p values <0.01 [see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article]). Participants in the hoarding minus OCD, OCD plus hoarding, and OCD minus hoarding groups reported similarly high levels of home-management difficulties, which were significantly greater than those reported in the anxiety disorder and community comparison groups. The OCD plus hoarding group demonstrated the greatest impairment in private leisure activities compared with the other four groups (see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article).

Discussion

The nosology of compulsive hoarding remains controversial (28) . To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically compare phenomenological and associated clinical features in OCD patients who have prominent hoarding symptoms with these features in patients who have severe hoarding but do not meet diagnostic criteria for OCD.

Similar to several previous studies on compulsive hoarding (11 , 12) , most patients with compulsive hoarding in our study tended to be women of advanced age. It is unclear whether this reflects a referral bias, with more women seeking help or willing to participate in research studies. However, a recent pediatric study on OCD reported a significantly higher prevalence of hoarding symptoms in girls relative to boys (53% versus 36%), which suggests that this sexual dimorphism may be present early in life and therefore may not merely reflect a referral bias (2) . The finding that individuals with compulsive hoarding were more likely to live alone and less likely to be married has also been reported in previous studies (12 , 29) and is likely to be an indirect reflection of the substantial levels of social disability associated with the disorder.

The high familial aggregation of hoarding in our sample (more than one-half of the participants in each of the two hoarding groups reported at least one relative with significant hoarding behavior) is similar to that found in previous studies (e.g., 20 , 30) . Interestingly, hoarding minus OCD participants also reported a higher family history of OCD relative to anxiety disorder and community comparison participants. Together, these findings may suggest distinct as well as common genetic and environmental factors implicated in OCD and hoarding phenotypes.

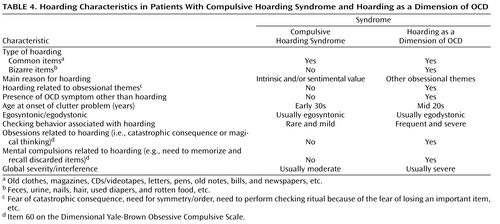

Although the phenomenology of hoarding behavior in the two hoarding groups was similar in some respects, there were several important differences between these groups. The extent of clutter reported in the two groups was substantial and comparable, but only some of the individuals with compulsive hoarding who met criteria for OCD collected bizarre items (e.g., feces, urine, nails, hair, used diapers, rotten food). While all of the participants in the hoarding minus OCD group reported hoarding as a result of the emotional and/or intrinsic value of a possession, 28% of individuals in the hoarding plus OCD group reported other obsessional ideas related to their hoarding, such as a fear of catastrophic consequences (e.g., something bad may happen if possessions are discarded), a fear of losing or discarding important items by mistake, a need for symmetry/ordering (e.g., the need to keep and organize a record of all life experiences), and a need to perform excessive checking rituals in relation to the hoarding. Consistent with previous reports (e.g., 31 ), the OCD plus hoarding group in our study had higher scores on the symmetry dimension of the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale relative to the OCD minus hoarding comparison group. Participants in both hoarding groups reported similar ages at onset of hoarding, although the OCD plus hoarding group reported experiencing clutter problems at an earlier age than the hoarding minus OCD group (25 years old versus 31 years old).

The severity of compulsive hoarding behavior was similar between the two hoarding groups on self-administered measures but not on the clinician-administered measure, suggesting that the presence of OCD may increase the severity of the behavior. As expected, the hoarding minus OCD group had minor or subclinical OCD symptoms, which were comparable with those in the anxiety disorder and community comparison groups on both self- and clinician-administered measures, further supporting the hypothesis that severe hoarding can be present in the absence of any clinically significant symptoms of OCD (7 , 20 , 32) .

Both hoarding groups had high rates of social phobia, which is consistent with previous findings (31 , 33) . Patients in the OCD plus hoarding group were more likely to endorse a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder compared with patients in the hoarding minus OCD group. The OCD plus hoarding group endorsed more cluster C personality traits. Additionally, the two hoarding groups did not differ in the total number of personality traits, but the OCD plus hoarding group endorsed significantly more personality traits than the OCD minus hoarding group, which is also consistent with previous reports (11 , 31 , 34) .

In our study, the association between hoarding and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was primarily mediated by the overlapping item content. After exclusion of the hoarding/collecting criterion, the number of endorsed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder criteria was comparable in all four patient groups, which suggests that individuals with compulsive hoarding are not more likely than individuals with other psychiatric disorders to endorse obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. However, this finding is contrary to previous studies that found obsessive-compulsive personality disorder to be associated with hoarding after removal of the hoarding/collecting criterion (11 , 31 , 34) . Methodological differences between these studies and the present study may explain this discrepancy.

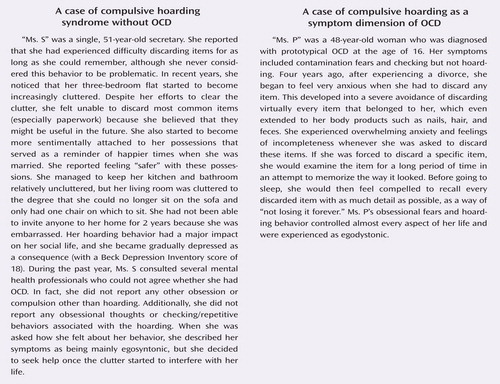

Our findings support the hypothesis of compulsive hoarding as a distinct clinical syndrome, which is highly comorbid with OCD as well as with other forms of psychopathology, such as social phobia (11 , 31) . Individuals who demonstrate this form of hoarding account for the majority of patients with compulsive hoarding, independent of their axis I diagnostic status. Almost invariably, these patients report hoarding as the result of 1) a fear that they may need items in the future (intrinsic value) or 2) a strong emotional attachment to their possessions, as described by Frost and Hartl (1) . These individuals do not hoard bizarre items or rubbish. However, while this psychopathological profile is also consistent with most patients with OCD plus hoarding, some patients with OCD (28% of patients in the OCD plus hoarding group in the present study) display severe hoarding symptoms that are associated with more conventional OCD themes, such as magical thoughts about something bad happening, a need for symmetry, and checking rituals associated with the fear of losing possessions. These patients can hoard bizarre items of no apparent value—or even rubbish—and tend to have a more severe and disabling form of the disorder.

There are several limitations to our study. Despite including one of the largest samples of well-characterized individuals with severe compulsive hoarding, the study may still not be powered to detect more subtle differences between the groups assessed. Future investigations should include larger samples to confirm our findings. Additionally, we relied on the participants’ self-reports rather than pictorial or in situ assessments of the severity of the clutter in their living spaces. In contrast to most of the nonhoarding OCD participants, the majority of individuals with compulsive hoarding (who seldom seek help) were recruited from nonclinical settings. However, the crucial comparison of the two hoarding groups was minimally affected by this potential drawback because most individuals in these groups were recruited via advertisement and support groups.

In summary, compulsive hoarding appears to be a syndrome that is separate from OCD in most cases and is associated with substantial levels of disability and social isolation. In some cases, however, hoarding can be considered a symptom of OCD and has special features ( Table 4 , Figure 1 ). It is presently unclear whether, in such cases, hoarding should be considered a primary symptom dimension of OCD or a behavior that is secondary to other OCD symptom dimensions. These results have implications for the future classification of OCD and compulsive hoarding in the next edition of DSM. If replicated and sufficient consensus is achieved, our results would support the inclusion of hoarding as a separate syndrome or OCD-spectrum disorder with its own diagnostic criteria and possibly as a symptom dimension of OCD as well. A recent survey among international OCD experts revealed that most of our colleagues would view these developments favorably (35) . However, more research is required before a decision can be reached. One important first step will be to operationalize the diagnostic criteria for the compulsive hoarding syndrome as well as for hoarding as a symptom dimension of OCD.

a Although between 15% and 40% of patients with OCD endorse hoarding and saving compulsions, these symptoms are only disabling for a small proportion of these individuals (approximately 5%). Conversely, approximately 50% of patients who meet criteria for compulsive hoarding syndrome (1) have comorbid OCD (i.e., the presence of clinically significant obsessive-compulsive symptoms other than hoarding). The great majority of patients with compulsive hoarding syndrome plus OCD are phenomenologically comparable with those who do not have comorbid OCD. However, in a small subset of patients with compulsive hoarding with OCD, the hoarding behavior has special characteristics and is clearly associated with obsessional themes. It is currently unclear whether in these cases hoarding should be considered a primary symptom dimension of OCD or a behavior that is secondary to other OCD symptom dimensions. Whether the symptom dimensions of OCD should be defined based on the observable behavior (e.g., checking, hoarding) or the motivation driving these behaviors (e.g., fear of harm, fear of loosing things, etc.) is an important question that requires further theoretical development and empirical research.

1. Frost RO, Hartl TL: A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:341–350Google Scholar

2. Mataix-Cols D, Nakatani E, Micali N, Heyman I: The structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in pediatric OCD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008 Mar 14; [Epub ahead of print]Google Scholar

3. Hanna GL, Yuwiler A, Coates JK: Whole blood serotonin and disruptive behaviors in juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:28–35Google Scholar

4. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:743–758Google Scholar

5. Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA, Baer L: Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1409–1416Google Scholar

6. Mataix-Cols D, Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF: A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:228–238Google Scholar

7. Steketee G, Frost R: Compulsive hoarding: current status of the research. Clin Psychol Rev 2003; 23:905–927Google Scholar

8. Saxena S: Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? Implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:380–384Google Scholar

9. Samuels J, Shugart YY, Grados MA, Willour VL, Bienvenu OJ, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Wang Y, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, Piacentini J, Pauls DL, Cullen B, Rasmussen SA, Hoehn-Saric R, Valle D, Liang K-Y, Riddle MA, Nestadt G: Significant linkage to compulsive hoarding on chromosome 14 in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:493–499Google Scholar

10. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

11. Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF, Warren R: Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:1071–1081Google Scholar

12. Grisham JR, Brown TA, Savage CR, Steketee G, Barlow DH: Neuropsychological impairment associated with compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45:1471–1483Google Scholar

13. Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J: Measurement of compulsive hoarding: Saving Inventory–Revised. Behav Res Ther 2004; 42:1163–1182Google Scholar

14. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Herqueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22–33; quiz 4–57Google Scholar

15. Bobes J: A Spanish validation study of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Eur Psychiatry 1998; 13:198s–199sGoogle Scholar

16. Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Dunbar GC: The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:224–231Google Scholar

17. Hyler SE: PDQ–4 and PDQ–4+ Instructions For Use. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1997Google Scholar

18. Calvo Pinero N, Caseras Vives X, Gutierrez Ponce De Leon F, Torrubia Beltri R: Spanish version of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–4+ (PDQ–4+). Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2002; 30:7–13Google Scholar

19. Rosario-Campos MC, Miguel EC, Quatrano S, Chacon P, Ferrao Y, Findley D, Katsovich L, Scahill L, King RA, Woody SR, Tolin D, Hollander E, Kano Y, Leckman JF: The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): an instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11:495–504Google Scholar

20. Seedat S, Stein DJ: Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a preliminary report of 15 cases. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 56:17–23Google Scholar

21. Tortella-Feliu M, Fullana MA, Caseras X, Andion O, Torrubia R, Mataix-Cols D: Spanish version of the Savings Inventory–Revised: adaptation, psychometric properties, and relationship to personality variables. Behav Modif 2006; 30:693–712Google Scholar

22. Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, Salkovskis PM: The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess 2002; 14:485–496Google Scholar

23. Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ: Psychometric properties and construct validity of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised: replication and extension with a clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord 2006; 20:1016–1035Google Scholar

24. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Google Scholar

25. Sanz J, Vázquez C: Fiabilidad, validez y datos normativos del inventario para la depresión de Beck. Psicothema 1998; 10:303–318Google Scholar

26. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH: The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:461–464Google Scholar

27. Marks IM: Behavioural Psychotherapy. London, Institute of Psychiatry, 1986Google Scholar

28. van Grootheest DS, Cath DC: Compulsive hoarding and OCD: Two distinct disorders? Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1435Google Scholar

29. Frost RO, Gross RC: The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther 1993; 31:367–381Google Scholar

30. Winsberg ME, Cassic KS, Koran LM: Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a report of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:591–597Google Scholar

31. Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ 3rd, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Cannistraro PA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Rasmussen SA, Pauls DL, Willour VL, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G: Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45:673–686Google Scholar

32. Grisham JR, Brown TA, Liverant GI, Campbell-Sills L: The distinctiveness of compulsive hoarding from obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2005; 19:767–779Google Scholar

33. Wheaton M, Timpano KR, Lasalle-Ricci VH, Murphy D: Characterizing the hoarding phenotype in individuals with OCD: associations with comorbidity, severity and gender. J Anxiety Disord 2008; 22:243–252Google Scholar

34. Mataix-Cols D, Baer L, Rauch SL, Jenike MA: Relation of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions of obsessive-compulsive disorder to personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:199–202Google Scholar

35. Mataix-Cols D, Pertusa A, Leckman JF: Issues for DSM-V: How should obsessive-compulsive and related disorders be classified? Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1313–1314Google Scholar