Efficacy of Adjunctive Aripiprazole to Either Valproate or Lithium in Bipolar Mania Patients Partially Nonresponsive to Valproate/Lithium Monotherapy: A Placebo-Controlled Study

Abstract

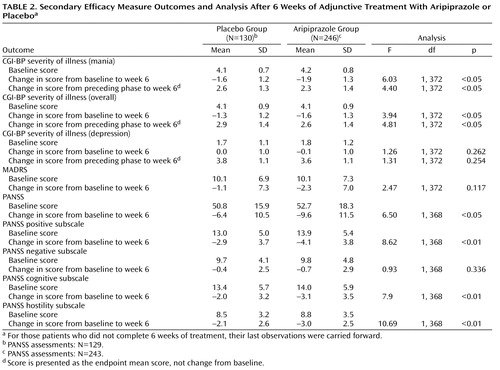

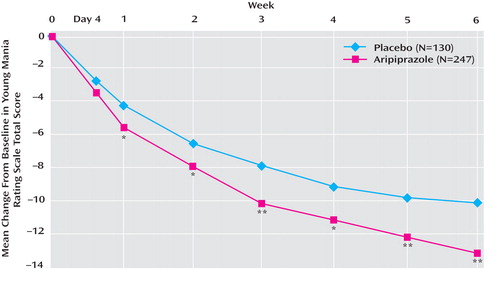

Objective: The authors evaluated the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in bipolar I patients with mania partially nonresponsive to lithium/valproate monotherapy. Method: This multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study included outpatients experiencing a manic or mixed episode (with or without psychotic features). Patients with partial nonresponse to lithium/valproate monotherapy (defined as a Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≥16 at the end of phases 1 and 2, with a decrease of ≤25% between phases) with target serum concentrations of lithium (0.6–1.0 mmol/liter) or valproate (50–125 μg/ml) were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to adjunctive aripiprazole (N=253; 15 or 30 mg/day) or placebo (N=131) for 6 weeks. Results: Mean improvement from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale total score at week 6 (primary endpoint) was significantly greater with aripiprazole (–13.3) than with placebo (–10.7). Significant improvements in Young Mania Rating Scale total score with aripiprazole versus placebo occurred from week 1 onward. In addition, the mean improvement in Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Version (CGI-BP) severity of illness (mania) score from baseline to week 6 was significantly greater with aripiprazole (–1.9) than with placebo (–1.6). Discontinuation rates due to adverse events were higher with aripiprazole than with placebo (9% versus 5%, respectively). Akathisia was the most frequently reported extrapyramidal symptom-related adverse event and occurred significantly more frequently among those receiving aripiprazole (18.6%) than among those receiving placebo (5.4%). There were no significant differences between treatments in weight change from baseline to week 6 (+0.55 kg and +0.23 kg for aripiprazole and placebo, respectively; last observation carried forward). Conclusions: Adjunctive aripiprazole therapy showed significant improvements in mania symptoms as early as week 1 and demonstrated a tolerability profile similar to that of monotherapy studies.

Mood stabilizers in combination with atypical antipsychotics are a first-line treatment approach for severe manic or mixed bipolar episodes (1 – 3) . For mildly ill patients with bipolar disorder, combination therapies are generally a second-line approach (1) , but mood stabilizer and antipsychotic combinations are widely used (1 , 4) . The efficacy of such regimens has been demonstrated in several randomized, controlled studies (5 – 10) ; however, some studies failed to separate the primary efficacy parameters from placebo (5 – 7) and most did not prospectively ensure patient partial nonresponse using well-defined rigorous criteria.

Studies have shown that the atypical antipsychotic aripiprazole is effective and well tolerated in the treatment of acute bipolar mania (11 , 12) , and it has shown superiority to haloperidol in response rates and tolerability in a 12-week acute mania trial (13) . Furthermore, aripiprazole monotherapy was superior to placebo in maintaining efficacy in patients with a recent manic/mixed episode who were stabilized and maintained on a regimen of aripiprazole for at least 6 weeks (14 , 15) . However, in a fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in the treatment of acute mania, aripiprazole did not separate from placebo despite similar symptom improvements to those seen in other studies (Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc., unpublished 2003 data), and aripiprazole monotherapy did not demonstrate superior efficacy to placebo at endpoint in two studies in bipolar depression (16) .

The present study is the first randomized, controlled study to investigate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole and either lithium or valproate compared with lithium or valproate plus placebo for the treatment of patients with bipolar I mania who were partially nonresponsive to lithium/valproate monotherapy.

Method

Patients

Eligible patients were ages 18 years or older with DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed type (with or without psychotic features); diagnosis was confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Patients had a history of at least one previous manic or mixed episode that required hospitalization and/or treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic.

Exclusion criteria were hospitalization for current manic or mixed episode for more than 3 weeks; previous nonresponse to treatments for manic symptoms; diagnosis of bipolar II disorder or rapid cycling bipolar disorder; history of substance abuse or dependence; significant risk of committing suicide; recent treatment with a long-acting antipsychotic; or known sensitivity to any of the study drugs. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design and Treatments

Phase 1 was a screening period (3–28 days, with an extension to 42 days with permission) during which medications other than lithium or valproate were discontinued. For patients not currently receiving a mood stabilizer, the investigators determined which medication to initiate. Patients were required to have a therapeutic serum level of lithium (0.6–1.0 mmol/liter) or valproate (50–125 μg/ml) and a Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≥16 at the end of screening. Median duration of treatment with lithium/valproate in phase 1 was 16 days (range=3–69 days) in the placebo group and 16 days (range=1–76 days) in the aripiprazole group.

Phase 2 was a 2-week baseline period during which patients continued to receive open-label lithium or valproate monotherapy. At week 2, patients with confirmed partial nonresponse (defined as a Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≥16 during phase 1 and at the end of phase 2, with a decrease of ≤25% between phases) were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either adjunctive aripiprazole (15 mg/day) or adjunctive placebo during the 6-week, double-blind phase (phase 3), stratified by type of mood stabilizer. Aripiprazole dose could be adjusted after week 1 (to 30 mg/day) based on tolerability or clinical response.

During baseline mood stabilizer treatment (phase 2), lorazepam (≤4 mg/day) or equivalents were permitted during week 1 and week 2 (≤3 mg/day). Propranolol (maximum dose of 20 mg t.i.d.) was also permitted. During double-blind treatment (phase 3), patients were permitted the use of benzodiazepines (≤2 mg/day of lorazepam or equivalents) for a maximum of 10 days during the first 4 weeks only. Anticholinergic therapy (benztropine mesylate or equivalents, ≤2 mg/day) and propranolol (maximum dose of 20 mg t.i.d., not to be taken within 8 hours of efficacy or safety assessment) were permitted for extrapyramidal symptoms. Propranolol for the treatment of heart disease was also permitted among those patients receiving it prior to enrollment.

Assessments

During double-blind treatment, efficacy was assessed at day 4 and thereafter at weekly intervals until week 6. The primary efficacy measure was the mean change from baseline to week 6 in Young Mania Rating Scale total score (last observation carried forward). The key secondary measure was the mean change from baseline to week 6 in Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Version (CGI-BP) severity of illness (mania) score. Other secondary measures at week 6 included rates of response (proportion of patients demonstrating ≥50% improvement from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale total score) and remission (proportion of patients achieving Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12); mean change from preceding phase in CGI-BP scores (mania, depression, and overall); mean change from baseline in CGI-BP severity of illness (overall) score and (depression) score; mean change from baseline in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score and PANSS positive, negative, cognitive, and hostility subscale scores; mean change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score; proportion of patients with emergent depression (defined as a MADRS total score ≥18 plus a ≥4-point increase from baseline in any two consecutive assessments); and time from random assignment to response and remission. A priori analyses were also performed on subgroups of patients receiving lithium or valproate. A post-hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate remission using criteria from both illness poles (proportion of patients achieving Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 plus a MADRS total score ≤8). Mean change from baseline to week 6 in Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Range of Impaired Function Tool total score was also evaluated.

Safety evaluations were based on reports of adverse events, vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, and weight and laboratory assessments. Severity of extrapyramidal symptoms was assessed using the Simpson-Angus Scale, the Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia, and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS).

Statistical Analyses

A sample size of 360 (aripiprazole: N=240; placebo: N=120) was chosen to provide 90% power to detect a difference of 3.2 points in the mean change from baseline to week 6 in Young Mania Rating Scale total score between adjunctive aripiprazole and adjunctive placebo. Analyses were performed on both the last observation carried forward and the observed data. Continuous efficacy measures were evaluated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and adjusted for treatment, baseline measurement, and type of mood stabilizer. A hierarchical testing procedure was used to preserve the significance level at 0.05. If the difference between aripiprazole and placebo on the primary efficacy measure was statistically significant (p≤0.05), then testing of the difference between aripiprazole and placebo on the key secondary efficacy measure could proceed at α=0.05. Testing of all other secondary endpoints was performed at the α=0.05 significance level without adjustment for multiple comparisons and multiple testing. Binary outcomes were analyzed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel general association statistics stratified by type of mood stabilizer. All tests were two-sided.

Time from random assignment to response and remission were evaluated by survival analyses and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Log-rank tests stratified by type of mood stabilizer were used to compare survival distributions between treatment groups. Parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the hazard ratio were obtained using a Cox regression model with treatment as a covariate, stratified by type of mood stabilizer.

Post-hoc analyses were conducted to calculate an effect size (d) using the Cohen method for paired samples (17) minus the difference in mean change in Young Mania Rating Scale total score between the placebo and the aripiprazole group, divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD). The number needed to treat, or the average number of patients who needed to be treated to show response in one additional patient, was also calculated. Post-hoc analysis of the change from baseline across all 11 items of the Young Mania Rating Scale was also conducted.

Results

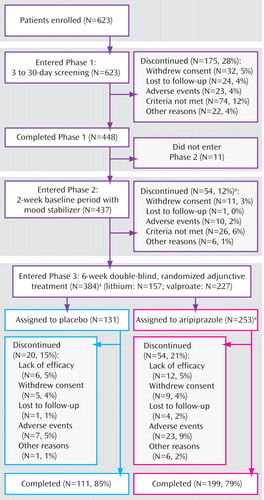

Patient Characteristics and Disposition

The progress of patients through the trial is shown in Figure 1 . In total, 384 patients completed the screening and baseline phase and were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with either placebo (N=131) or aripiprazole (N=253). Of the patients who discontinued the study during the baseline phase (N=54), 21 did so because they achieved response with lithium/valproate monotherapy (and thus could not meet criteria for study continuation). Double-blind treatment was completed by 85% and 79% of patients randomly assigned to placebo and aripiprazole, respectively. Discontinuation rates due to adverse events were higher for patients in the aripiprazole group than for patients in the placebo group (9% versus 5%; p=0.200). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were similar between treatment groups ( Table 1 ).

a One patient received double-blind study medication during phase 2 in error.

Study Treatments

Of the patients randomly assigned to double-blind treatment (N=384), 157 were receiving lithium and 227 were receiving valproate. For the patients assigned to adjunctive aripiprazole, the mean dose of aripiprazole during week 6 was 19.0 mg/day. For the lithium subgroup, the mean dose of lithium the day before starting adjunctive treatment was 994 mg/day and 1,119 mg/day for the placebo and aripiprazole arms, respectively. Mean lithium serum levels at baseline in these two groups were 0.77 mmol/liter (SD=0.17) and 0.78 mmol/liter (SD=0.22), respectively. The mean dose of lithium during week 6 of double-blind treatment was 985 mg/day and 1,160 mg/day for the placebo and aripiprazole groups, respectively. Mean lithium serum levels at week 6 (last observation carried forward) were similar in both groups (placebo: 0.72 mmol/liter [SD=0.22]; aripiprazole: 0.76 mmol/liter [SD=0.35]; t= −0.87, df=140, p=0.385). A similar proportion of patients in both arms had a serum lithium level within the therapeutic range at endpoint (placebo: 68.0%; aripiprazole: 69.9%). For the valproate subgroup, the mean dose the day before starting adjunctive treatment was 1,175 mg/day and 1,180 mg/day for the placebo and aripiprazole arms, respectively. The mean serum valproate level at baseline in the two groups was 77.2 μg/ml (SD=23.4) and 77.8 μg/ml (SD=21.0), respectively. The mean dose of valproate during week 6 of double-blind treatment was 1,179 mg/day and 1,225 mg/day for the placebo and aripiprazole groups, respectively. Similar mean serum valproate levels at endpoint (week 6; last observation carried forward) were seen between the two groups (placebo: 68.35 μg/ml [SD=23.92]; aripiprazole: 68.23 μg/ml [SD=23.63]; t=0.04, df=161, p=0.971). A similar proportion of patients in both arms had a serum valproate level within the therapeutic range at endpoint (placebo: 78.8%; aripiprazole: 80.0%).

More than 40% of patients received concomitant CNS medication. The most frequently taken CNS medications were anxiolytics (placebo: 24.6%; aripiprazole: 20.9%) and other analgesics and antipyretics (placebo: 23.1%; aripiprazole: 21.3%). A total of 47 (18.6%) patients in the aripiprazole group received a concomitant medication for the potential treatment of extrapyramidal symptoms, compared with nine (6.9%) patients in the placebo group.

Efficacy

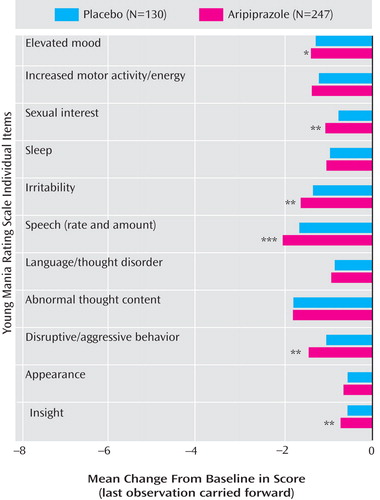

At week 6, adjunctive aripiprazole showed significantly greater improvements from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale total score than placebo (–13.3 [SD=7.9] versus –10.7 [SD=7.6]; F=9.54, df=1, 373, p<0.01; d=0.33) ( Figure 2 ). Aripiprazole plus mood stabilizer produced significantly greater improvements from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale total score than lithium/valproate monotherapy by week 1 and at all subsequent endpoints (p<0.05) ( Figure 2 ). In a post-hoc analysis, adjunctive aripiprazole did not worsen manic symptoms as measured by an item analysis of the Young Mania Rating Scale, and in addition demonstrated significant improvements relative to placebo on six of the 11 items: elevated mood, sexual interest, irritability, speech, disruptive/aggressive behavior, and insight ( Figure 3 ).

a Last observation carried forward. Mean scores at baseline were 22.7 and 23.1 for placebo and aripiprazole, respectively.

*p<0.05. **p<0.01.

*p<0.05. **p<0.01. ***p<0.001.

A priori analyses of each subgroup showed that adjunctive aripiprazole with valproate produced significantly (p<0.05) greater improvements in Young Mania Rating Scale total score than placebo from day 4 through week 6 (–14.0 [SD=7.8] versus –10.7 [SD=7.9]; F=9.06, df=1, 222, p<0.01; last observation carried forward). For the lithium subgroup, the improvement from baseline at week 6 with aripiprazole was numerically, albeit not significantly, greater than with adjunctive placebo (–12.4 [SD=8.1] versus –10.8 [SD=7.1]; F=1.40, df=1, 149, p=0.238; last observation carried forward). In the observed data, adjunctive aripiprazole produced significantly greater improvements in Young Mania Rating Scale total score than adjunctive placebo at week 5 (–13.7 [SD=6.8] versus –10.2 [SD=7.5]; F=6.24, df=1, 114, p<0.05) and week 6 (–14.7 [SD=6.5] versus –10.2 [SD=7.4]; F=11.00, df=1, 113, p≤0.001).

Adjunctive aripiprazole was also associated with significant reductions in CGI-BP severity of illness (mania) score versus placebo ( Table 2 ). Response rates were significantly higher with adjunctive aripiprazole than with placebo at week 5 (χ 2 =5.79, df=1, p≤0.05; last observation carried forward) ( Figure 4 ). At week 6, 62.8% of the aripiprazole group had responded to treatment, compared with 48.5% of the placebo group (χ 2 =7.07, df=1, p<0.01; last observation carried forward), and the number needed to treat was 7. Compared with placebo, aripiprazole also produced significantly higher remission rates at weeks 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 ( Figure 4 ). At week 6, the remission rate was 66.0% for aripiprazole and 50.8% for placebo (χ 2 =8.18, df=1, p<0.01; last observation carried forward), and the number needed to treat was 7. Post-hoc analysis using more stringent remission criteria (Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 plus a MADRS total score ≤8) also showed significantly higher remission rates with aripiprazole than with placebo at week 6 (50.2% versus 36.4%; χ 2 =6.44, df=1, p<0.05; last observation carried forward). Similar rates were observed in the lithium and valproate subgroups, although the differences between the two were not statistically significant (lithium: 51.0% versus 34.7%; χ 2 =3.51, df=1, p=0.061; valproate: 49.7% versus 37.5%; χ 2 =3.06, df=1, p=0.080).

a Defined as ≥50% improvement in Young Mania Rating Scale total score (last observation carried forward).

b Defined as achieving a Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 (last observation carried forward).

c Day 4: N=97.

d Day 4: N=191.

*p<0.05. **p≤0.01.

Time to response (number of events for aripiprazole: 178 [72.1%]; for placebo: 83 [63.8%]; hazard ratio=1.45) and time to remission (number of events for aripiprazole: 185 [74.9%]; for placebo: 87 [66.9%]; hazard ratio=1.48), as evaluated by survival curves, were both significantly in favor of aripiprazole (χ 2 =7.84, df=1, p<0.01 and χ 2 =9.04, df=1, p<0.01, respectively).

Adjunctive aripiprazole also produced a significantly greater improvement than placebo in the CGI-BP severity of illness (overall) score at week 6 (p<0.05; last observation carried forward) and significantly greater change than placebo from preceding phase in CGI-BP severity of illness (overall) and (mania) scores (both p values <0.05; last observation carried forward) ( Table 2 ). The improvement over placebo in MADRS score seen with aripiprazole was not statistically significant at endpoint (last observation carried forward). Analysis of the observed data demonstrated statistically significant improvements in MADRS scores for adjunctive aripiprazole versus adjunctive placebo at week 1 (–2.0 [SD=4.2] versus –0.2 [SD=5.8]; F=10.79, df=1, 343, p<0.01), week 5 (–3.8 [SD=4.9] versus –2.6 [SD=5.6]; F=4.03, df=1, 303, p<0.05), and week 6 (–3.5 [SD=6.2] versus –1.7 [SD=6.6]; F=5.90, df=1, 302, p<0.05).

The proportion of patients with emergent depression was significantly lower in the aripiprazole arm than the placebo arm (7.7% versus 16.9%; χ 2 =7.61, df=1, p<0.01). Similarly, fewer patients reported emergent depression in the aripiprazole arm for both the lithium subgroup (7.8% versus 24.0%; χ 2 =7.61, df=1, p<0.01) and valproate subgroup, although the difference in the valproate subgroup was not statistically significant (7.6% versus 12.5%; χ 2 =1.42, df=1, p=0.233).

Significantly greater improvements from baseline to week 6 were evident for aripiprazole compared with placebo in PANSS total score and PANSS positive, cognitive, and hostility subscale scores (p≤0.05; last observation carried forward), although there was no significant difference between treatments in PANSS negative subscale scores ( Table 2 ). There was a significant difference between groups in mean change from baseline to week 6 in Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Range of Impaired Function Tool total score favoring aripiprazole versus placebo (–1.8 versus –1.0; p=0.046).

Safety

During double-blind treatment, 53.8% (N=70) of patients in the adjunctive placebo group and 62.1% (N=157) of patients in the adjunctive aripiprazole group reported at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (p=0.140). Adverse events occurring at an incidence ≥5% in either treatment group are shown in Table 3 .

During double-blind treatment, serious adverse events were reported for 3.2% of aripiprazole patients and 2.3% of placebo patients; most frequent were psychiatric disorders typical of the patient population (aripiprazole: 2.4%; placebo: 2.3%). Most serious adverse events were judged to be unrelated or unlikely to be related to study medication.

Patients treated with adjunctive aripiprazole showed more extrapyramidal symptoms than patients in the placebo group. Adverse events related to treatment-emergent extrapyramidal symptoms were reported in 28.1% (N=71) of the aripiprazole group and 13.8% (N=18) of the placebo group. Of these patients, 25.4% (N=18) of the aripiprazole group and 22.2% (N=4) of the placebo group had resolved the adverse event by study end. The most frequently reported extrapyramidal symptom-related adverse event was akathisia (aripiprazole: 18.6%; placebo: 5.4%). Other extrapyramidal symptom-related adverse events occurred in <10% of patients in either group: tremor (placebo: 6.2%; aripiprazole: 9.1%); extrapyramidal disorder (placebo: 0.8%; aripiprazole: 4.7%); hypertonia (placebo: 0%; aripiprazole: 0.4%); hypokinesia (placebo: 0%; aripiprazole: 0.4%); muscle spasms (placebo: 0.8%; aripiprazole: 2.0%); dyskinesia (placebo: 0.8%; aripiprazole: 0.4%); and muscle twitching (placebo: 0%; aripiprazole: 0.4%). The lithium subgroup showed higher rates of akathisia (aripiprazole: 28.3%; placebo: 4.0%) and tremor (aripiprazole: 13.2%; placebo: 8.0%) than the valproate subgroup (aripiprazole: 11.6%; placebo: 6.3% and aripiprazole: 6.1%; placebo: 5.0%, respectively). Akathisia was generally mild to moderate in severity (aripiprazole: 15.8%; placebo: 4.6%); severe symptoms were reported in 2.8% and 0.8% of aripiprazole and placebo patients, respectively. For aripiprazole patients who reported akathisia with a maximum severity of mild, moderate, and severe, the corresponding median highest Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia score was 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The majority of akathisia in the aripiprazole group began in the first 3 weeks of treatment (89.4%). Akathisia occurring during double-blind treatment led to discontinuation in 13 aripiprazole patients (5.1%) and one placebo patient (0.8%). By the end of double-blind treatment, akathisia had resolved in 15 out of the 47 patients (31.9%) in the aripiprazole group and one out of the seven patients (14.3%) in the placebo group reporting this symptom. The median duration of resolved akathisia events was 8 days. For those subjects in the aripiprazole arm whose akathisia resolved during the study, two had their study medication dose adjusted (one patient received a dose reduction and one patient discontinued the study). Permitted concomitant medications (e.g., benztropine, propranolol) for akathisia were administered in 11 patients (73.3%). Akathisia resolved without intervention in three patients. The one patient in the placebo arm whose akathisia resolved at the end of the double-blind treatment phase had a dose reduction but did not receive any concomitant medication to treat the akathisia.

During adjunctive treatment, significant mean changes from baseline to the end of week 6 (last observation carried forward) were seen in Simpson-Angus Scale total scores (placebo: baseline score=10.5, change in score=0.07; aripiprazole: baseline score=10.5, change in score=0.73; F=9.05, df=1, 370, p<0.01) and Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia scores (placebo: baseline score=0.18, change in score=0.11; aripiprazole: baseline score=0.15, change in score=0.30; F=5.03, df=1, 370, p=0.026). Mean changes in AIMS total scores were not significantly different between treatment groups (placebo: baseline score=0.18, change in score= –0.10; aripiprazole: baseline score=0.25, change in score=0.08; F=3.57, df=1, 370, p=0.060).

Small changes from baseline in body weight were observed with aripiprazole (+0.55 kg [SD=2.66]) and placebo (+0.23 kg [SD=3.51]) at endpoint (last observation carried forward), with no statistically significant differences between groups (p=0.331). There were similar findings in the observed data (aripiprazole: +0.67 kg [SD=2.77]; placebo: +0.41 kg [SD=3.64]; p=0.499). There were no significant treatment differences in the mean change in weight from baseline to week 6 (last observation carried forward) in the lithium or valproate subgroups. The percentage of patients showing clinically significant weight gain (≥7% increase in weight from baseline to week 6; last observation carried forward) was similar in the two groups: 3.9% (N=5) in the placebo arm and 3% (N=7) in the aripiprazole arm. There were similar findings in the observed data and in the lithium and valproate subgroups.

There were no clinically meaningful differences between treatments in laboratory parameters, including total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose and triglycerides, and serum prolactin levels. Adjunctive aripiprazole plus valproate/lithium treatment was not associated with any clinically relevant changes in vital sign measurements or any ECG abnormalities.

Discussion

Aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate is efficacious and well-tolerated for patients with manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder who were partially nonresponsive to lithium/valproate monotherapy. Reduction in mania symptoms, as measured by change from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale total score, was significantly greater with adjunctive aripiprazole than with placebo. Importantly, aripiprazole improved symptoms as early as week 1, since rapid symptom relief is an established therapeutic goal in the management of bipolar mania. Consistent with a previously published Young Mania Rating Scale item analysis in an acutely manic population (18) , the present study shows that aripiprazole ameliorated the core symptoms of irritability and disruptive aggressiveness in an outpatient population. These symptoms can lead to challenges in maintaining healthy social and family interactions for patients with bipolar disorder.

Aripiprazole also showed statistically significant improvements on several other key indicators of clinical efficacy. A significantly greater proportion of patients in the aripiprazole group versus placebo group met criteria for remission (Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12). Even in the post-hoc analysis using stricter remission criterion (Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 plus a MADRS total score ≤8), the difference between aripiprazole and placebo was statistically significant. Furthermore, time to remission was achieved sooner with adjunctive aripiprazole than with placebo and aripiprazole produced significantly greater remission and response rates than placebo at weeks 3 and 5, respectively.

Interestingly, the percentage of aripiprazole patients meeting criteria for remission was higher than the percentage meeting criteria for response (66.0% versus 62.8%). This illustrates the effect of baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score on outcome, as patients in this study started with a relatively lower Young Mania Rating Scale total score (placebo: 22.7; aripiprazole: 23.1) than patients in other acute mania studies (Young Mania Rating Scale total score ∼30). It also reflects the difference between the two measures (response rates measure relative effect, while remission rates measure absolute effect) and highlights the importance of assessing both response and remission in bipolar mania (19) .

These results compare favorably to similar trials investigating the adjunctive use of atypical agents with valproate or lithium in which risperidone (8) , olanzapine (20) , and quetiapine (9) improved Young Mania Rating Scale total score versus adjunctive placebo. The findings reported here are particularly significant as this study adopted more rigorous criteria for nonresponse, plus a 2-week baseline phase to confirm lithium/valproate monotherapy partial nonresponse. Furthermore, while previous studies have shown positive results, others have failed to demonstrate efficacy on the primary efficacy endpoints (5 – 7) .

This study was designed to detect a treatment difference between aripiprazole and placebo in the total population and was not powered to detect treatment differences between aripiprazole and placebo in subgroup analyses. Nonetheless, adjunctive aripiprazole showed treatment differences from placebo in both valproate and lithium subgroups. In analyses of the last observations carried forward, treatment differences were significant in the valproate but not the lithium subgroup; in analyses of the observed data, treatment differences were significant in both subgroups. This finding is not unique to aripiprazole, since a previous study of adjunctive olanzapine and lithium/valproate versus lithium/valproate alone also failed to show significant difference in response between the adjunctive olanzapine group and the lithium subgroup (20) .

Importantly, there was significantly less emergent depression in the aripiprazole group than in the placebo group, suggesting that improvement in mania was not associated with a destabilization into depression, a key challenge in treating bipolar disorder (21) . Moreover, aripiprazole was associated with improvements in psychosocial functionality, suggesting that improved efficacy may translate into better social and family outcomes.

From a clinical standpoint, it is important to establish the safety and tolerability of adjunctive therapies, even if tolerability as monotherapy is well established. Aripiprazole plus lithium/valproate was well tolerated and adverse events were similar to those observed with aripiprazole monotherapy (11 – 14) . Of particular interest is the greater incidence of akathisia in the subgroup of patients taking lithium, although the study was not powered to detect differences between subgroups. However, most reports were mild to moderate in intensity and confirmed by Barnes analysis. The majority of akathisia events occurred early in the study, suggesting potential sensitivity to the initial dose of aripiprazole—a lower starting dose may have been more tolerable. Additionally, akathisia resolved by the end of double-blind treatment in one third of patients. As some events resolved spontaneously, one might consider whether some treatment-emergent akathisia events were actually true akathisia. Assessments of akathisia, as currently defined in clinical trials nomenclature, might be capturing clinical features related to other syndromes, such as activation or anxiety symptoms. Adjunctive aripiprazole was not associated with increases in body weight compared with placebo, or with clinically significant weight gain, consistent with previous studies of aripiprazole monotherapy (11 – 13) . This may have particular clinical relevance as both lithium and valproate are associated with weight gain (22 , 23) .

This is the most rigorous study to date in terms of clearly demonstrating partial nonresponse to an optimal dose of lithium/valproate monotherapy in a well-defined, prospective manner. Another strength of this study is the relatively low discontinuation rate during double-blind treatment. Study limitations include the fact that rapid-cycling bipolar patients were excluded, patients were not randomly assigned to lithium or valproate subgroups, and the study was not powered to compare subgroups. Also, the longer-term benefits of this combination therapy need to be established.

Conclusion

Aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy to valproate/lithium was shown to provide a greater improvement in mania symptoms as early as week 1 than with lithium or valproate alone. The safety and tolerability profile of adjunctive aripiprazole was similar to that observed in previous aripiprazole monotherapy studies in patients with bipolar mania. Aripiprazole in combination with valproate/lithium is an effective and generally well-tolerated treatment for patients with manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder partially nonresponsive to lithium/valproate monotherapy.

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, second edition. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(suppl):S1–S50Google Scholar

2. Goodwin GM; Consensus Group of the British Association for Psychopharmacology: Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2003; 17:149–173Google Scholar

3. Grunze H, Kasper S, Goodwin G, Bowden C, Baldwin D, Licht R, Vieta E, Möller HJ; World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorders: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of bipolar disorders, part I: treatment of bipolar depression. World J Biol Psychiatry 2002; 3:115–124Google Scholar

4. Bowden CL: Making optimal use of combination pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65(suppl 15):21–24Google Scholar

5. Yatham LN, Grossman F, Augustyns I, Vieta E, Ravindran A: Mood stabilisers plus risperidone or placebo in the treatment of acute mania: international, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:141–147Google Scholar

6. Weisler RH, Dunn J, English P: Ziprasidone in adjunctive treatment of acute bipolar mania: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 13(suppl 4):S344–S345Google Scholar

7. Yatham LN, Vieta E, Young AH, Möller HJ, Paulsson B, Vågerö M: A double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine as an add-on therapy to lithium or divalproex for the treatment of bipolar mania. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007; 22:212–220Google Scholar

8. Sachs GS, Grossman F, Ghaemi SN, Okamoto A, Bowden CL: Combination of a mood stabilizer with risperidone or haloperidol for treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of efficacy and safety. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1146–1154Google Scholar

9. Sachs G, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, Mullen JA, Brecher M, Devine NA, Sweitzer DE: Quetiapine with lithium or divalproex for the treatment of bipolar mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:213–223Google Scholar

10. Yatham LN, Paulsson B, Mullen J, Vågerö AM: Quetiapine versus placebo in combination with lithium or divalproex for the treatment of bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:599–606Google Scholar

11. Keck PE Jr, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A, Ingenito G; Aripiprazole Study Group: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1651–1658Google Scholar

12. Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Impellizzeri C, Kaplita S, Rollin L, Iwamoto T; Aripiprazole Study Group: Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol 2006; 20:536–546Google Scholar

13. Vieta E, Bourin M, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Swanink R, Iwamoto T; Aripiprazole Study Group: Effectiveness of aripiprazole v. haloperidol in acute bipolar mania: double-blind, randomised, comparative 12-week trial. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 187:235–242Google Scholar

14. Keck PE Jr, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R; Aripiprazole Study Group: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:626–637Google Scholar

15. Keck PE Jr, Calabrese JR, McIntyre RS, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Eudicone JM, Carlson BX, Marcus RN, Sanchez R; Aripiprazole Study Group: Aripiprazole monotherapy for maintenance therapy in bipolar I disorder: a 100-week, double-blind study versus placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:1480–1491Google Scholar

16. Thase ME, Jonas A, Khan A, Bowden CL, Wu X, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Marcus RN, Owen R: Aripiprazole monotherapy in non-psychotic bipolar I depression: results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacology (in press)Google Scholar

17. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

18. Frye MA, Eudicone JM, Pikalov A, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Carlson BX: Aripiprazole efficacy in irritability and disruptive-aggressive symptoms: Young Mania Rating Scale line analysis from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol (in press)Google Scholar

19. Montgomery DB: ECNP Consensus Meeting March 2000 Nice: guidelines for investigating efficacy in bipolar disorder. European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001; 11:79–88Google Scholar

20. Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, Zarate CA Jr, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Kupfer DJ, Baker RW, Risser RC, Keeter EL, Feldman PD, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:62–69Google Scholar

21. Vieta E: The treatment of mixed states and the risk of switching to depression. Eur Psychiatry 2005; 20:96–100Google Scholar

22. Keck PE, McElroy SL: Bipolar disorder, obesity, and pharmacotherapy-associated weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1426–1435Google Scholar

23. Vieta E: Maintenance therapy for bipolar disorder: current and future management options. Expert Rev Neurother 2004; 4(6 Suppl 2):S35–S42Google Scholar