The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis in Preschool- and Elementary School-Age Children Exposed to Motor Vehicle Accidents

Abstract

Objective: Increasingly, children are being diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, including preschool-age children. These diagnoses in young children raise questions pertaining to 1) how diagnostic algorithms for individual disorders should be modified for young age groups, 2) how psychopathology is best detected at an early stage, and 3) how to make use of multiple informants. The authors examined these issues in a prospective longitudinal assessment of preschool- and elementary school-age children who were exposed to a traumatic event. Method: Participants were 114 children (age range: 2–10 years) who had experienced a motor vehicle accident. Parents and older children (age range: 7–10 years) completed structured interviews 2–4 weeks (initial assessment) and 6 months (6-month follow-up) after the traumatic event. A recently proposed alternative symptom algorithm for diagnosing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was utilized and compared with the standard DSM-IV algorithms for diagnosing PTSD and acute stress disorder. Results: At the 2- to 4-week assessment, 11.5% of the children met conditions for a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report, and 13.9% met criteria for this diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up. These percentages were much higher than those for DSM-IV diagnoses of acute stress disorder and PTSD. Among 7- to 10-year-old subjects, the use of combined parent- and child-reported symptoms to derive a diagnosis resulted in an increased number of children in this age group who were identified with psychiatric illness relative to the use of parent report alone. Agreement between parent and child on symptoms for 1) a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria and 2) diagnoses of DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD in this age group was poor. Among 2- to 6-year-old subjects, the alternative algorithm PTSD diagnosis per parent report was a more sensitive predictor of later onset psychopathology relative to a diagnosis of DSM-IV acute stress disorder or PTSD per parent report. However, among 7- to 10-year-old subjects, a combined symptom report (from both parent and child) was optimal in predicting posttraumatic psychopathology. Conclusions: These findings support the use of the proposed alternative algorithm for assessing PTSD in young children and suggest that the diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria is stable from the acute phase onward. When both parent- and child-reported symptoms are utilized for the assessment of PTSD among 7- to 10-year-old children, the alternative algorithm and DSM-IV criteria have broad comparable validity. However, in the absence of child-reported symptoms, the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report appears to be an optimal diagnostic measure of PTSD among children in this age group, relative to the standard DSM-IV algorithm for diagnosing the disorder.

There is growing consensus that many adult psychiatric disorders have their origins in childhood and adolescence (1) . Consistent with this broad perspective, there has been a shift in the field of developmental psychiatry toward identifying disorders in young children (2) . Consequently, DSM-IV criteria are increasingly “down-aged” in order to diagnose psychopathology in children, even in preschool-age children (3) . However, the best diagnostic criteria for these age groups remain undetermined (4) . This shift of focus toward younger populations highlights a number of key issues that have broad implications for developmental psychiatry. We examined three of these issues in the present study.

First, although there is a growing consensus that the comprehensive architecture of DSM-IV may be applicable in young age groups (5) , there are important questions regarding whether current diagnostic algorithms for individual disorders require modification (e.g., 6 ) in order to avoid under- or misdiagnosis in children. The validation of alternative diagnostic algorithms for assessing very young children has implications for the assessment of older children as well as adults. Thus, in the assessment of young children, alternative algorithms may possess greater validity than extant DSM-IV criteria or may be more practical to apply (7) .

Second, early detection of psychopathology in children remains a concern. Early detection involves 1) identifying conditions with a potential lifetime course as early as possible in the developing child and 2) identifying conditions that may have a more limited course among a particular age group as early as possible in the evolution of such conditions. The issue of early detection is critical in the prevention of chronic disorders in childhood and adolescence (4) .

Last, the optimal use of multiple informants for deriving diagnoses in young children is also important. In preschool-age children, there is a limited role for child self-report (8) . However, the utility of child self-report in diagnosing elementary school-age children (with the potential to supplement parent- or teacher-reported symptoms with nonoverlapping data) remains relatively unexplored. Furthermore, integration of child- and parent-reported symptoms in the assessment of older children provides a means to evaluate the extent to which parent-reported symptoms alone may underestimate symptoms in younger children.

In the present study, we examined these three issues with respect to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in preschool- and elementary school-age children (age range: 2–10 years) who experienced a motor vehicle accident, which is a common trauma among young age groups.

An Alternative Algorithm for PTSD

To our knowledge, there is only one published large-scale community survey of PTSD in preschool-age children (age range: 2–5 years). In this survey, the prevalence rate, according to DSM-III-R criteria, was 0.1% (9) relative to 1%–3.5% in comparable surveys among adult subjects (10 , 11) and 3%–6% in comparable surveys among adolescent subjects (12 , 13) . These data suggest that the diagnosis of PTSD in younger children may not be optimally reflected by the current DSM diagnostic algorithm. An alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD in preschool-age children based on parent-reported symptoms has been proposed and, to date, has received encouraging preliminary support (8 , 14 – 16) . This alternative diagnostic algorithm for diagnosing PTSD necessitates reductions in the requisite number of endorsed avoidance symptoms (from three symptoms to one symptom) as well as the removal of DSM-IV criterion A2 concerning emotion at the time of trauma. Preliminary proposals have also recommended extending the alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD to older elementary school-age children (age range: 7–11 years), although empirical support for this age group is presently more limited (8) .

The decision to adopt an alternative algorithm for conceptualizing psychopathology in younger populations constitutes a major nosological shift. It is therefore critical that the empirical foundation for such a decision be comprehensive. Despite considerable progress in developing the alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD (8 , 14 – 16) , significant gaps remain in the validity of the diagnosis using this algorithm.

To our knowledge, there have been no attempts to examine the validity of the diagnosis of PTSD in preschool-age children during the acute posttraumatic phase (i.e., within the first month following a traumatic event) using the alternative algorithm or to compare the diagnosis based on criteria from the alternative algorithm with that of the established DSM-IV diagnosis for this acute period, which is referred to as acute stress disorder. This is not surprising, since—to the best of our knowledge—there are no studies that have examined the validity of any formal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress during the acute aftermath of trauma in preschool-age children.

In the present study, we compared the prevalence rates for 1) a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report, 2) a diagnosis of acute stress disorder based on DSM-IV criteria per parent report, and 3) a diagnosis of PTSD based on DSM-IV criteria (without the duration criterion) per parent report in preschool- and elementary school-age children assessed within the first 4 weeks following a traumatic event. We also examined the convergent validity of all three diagnoses with respect to a standardized instrument utilizing parent report for assessing posttraumatic stress.

Although longitudinal studies regarding the course of posttraumatic reactions in preschool-age children exist (17 , 18) , we are aware of only one study (19) that has reported longitudinal data addressing the course of PTSD in subjects who were diagnosed based on criteria from the alternative algorithm. However, this study used a carefully selected sample of children who already showed symptoms of PTSD at baseline (approximately 2 months following the traumatic event) and showed no diagnostic continuity for PTSD at the 1-year follow-up. To our knowledge, there are no longitudinal studies that have demonstrated diagnostic stability for PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria over a period of up to 2 years. Given the widespread concern regarding the stability of psychiatric diagnoses in younger age groups—as a result of the rapidity of developmental changes (20) —it is critical to demonstrate diagnostic continuity for any proposed algorithm for assessing individuals in these age groups. We examined the stability of diagnoses in the present study by conducting follow-up assessments of our study sample of children up to 6 months after their traumatic experience.

In addition, the validity of a diagnosis of PTSD using the alternative algorithm criteria in the assessment of preadolescent-age (elementary school) children is a concern that relates to the generalizability of novel algorithms that are validated in very young age groups. Although one preliminary study examined the diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria in the assessment of older children (8) , the study was cross-sectional and had a small sample size (N=11). Further studies of parent-reported symptoms of PTSD among preadolescent children (with appropriate comparisons with DSM-IV diagnoses of acute stress disorder and PTSD) are needed to more fully explore the broader developmental implications of this alternative algorithm.

Early Detection

An important challenge in posttraumatic stress research is identifying those individuals in the acute posttraumatic phase who are most likely to experience chronic difficulties and present with PTSD in the future. One reason for the introduction of the acute stress disorder diagnosis in DSM-IV was to establish a method for identifying trauma survivors, within the first month following their traumatic experience, who are most at risk for developing PTSD (21) . To this end, the acute stress disorder diagnosis requires the presence of dissociative symptoms, which have been viewed as key predictors of longer-term psychopathology (e.g., 22 ). Moreover, the use of the dissociation symptom cluster and, consequently, the use of acute stress disorder as a diagnosis in the early detection of individuals who are most at risk for developing PTSD have been called into question in studies of both adults (23) and older children (24 – 26) . However, we are unaware of any studies that have examined the prognostic power of acute stress disorder among children between the ages of 2 and 10 years or whether a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria in this age group offers a superior means of identifying children who are most at risk for developing psychopathology. Thus, we examined these two issues in the present study.

Multiple Informants

Currently, it is standard practice within the field of developmental psychiatry to utilize multiple informants to derive diagnoses (4 , 27) . However, for elementary school-age children (age range: 7–10 years), data concerning informant validity are less extensive (2) , and data are significantly poor in the case of PTSD (28) and absent in the case of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria, for which the only study examined adolescent subjects (age range: 11–18 years [8] ). In the present study, we addressed this shortfall by deriving diagnoses based on child-, parent-, and combined parent-child-reported symptoms among 7- to 10-year-old children (per criteria for the alternative symptom algorithm and DSM-IV PTSD and acute stress disorder). This step was initiated in order to 1) examine relative prevalence estimates, 2) assess levels of interinformant agreement, and 3) provide a method for assessing the degree to which parent-reported symptoms alone might have underestimated the prevalence rates in younger age groups when valid child-reported symptoms were not possible.

One key concern when evaluating psychopathology in samples of young children is how to assess the relative importance and validity of data from the children and their parents. One way to determine this is to assess the prognostic power of the reported symptoms from different informants (e.g., parent, child) to predict later psychopathology within longitudinal designs (29) . To date, there is a paucity of such data in the field of developmental psychiatry and no such data pertaining to posttraumatic psychopathology in young children. Evaluating the relative prognostic power of the perspectives of different informants (assessed during the acute posttraumatic phase) in the prediction of later development of PTSD has potentially broad implications for the field and was the final focus of the present study.

Method

Participants

Children (age range: 2–10 years) were recruited to participate in the study from three emergency departments in London. Eligible children had attended an emergency department following a motor vehicle accident. The three emergency departments that participated in the study are situated in low socioeconomic boroughs in England, with high rates of immigration and scarce resources. Exclusion criteria were mental retardation, moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (i.e., posttraumatic amnesia [inability to recollect events ≥24 hours after experiencing a traumatic event]), or the inability of a child’s parent or caregiver to speak English.

A total of 312 children were eligible to participate in the study. Of these, the families of 120 children (38.5%) could not be reached as a result of incomplete or inaccurate data provided by the emergency department. Of the 192 families who were contacted, 72 (37.5%) indicated that they did not have time to participate or were not interested in participating in the study. Of the 120 families remaining, six (3.2%) chose not to participate because they feared that they might upset their child. Thus, 114 families (60.0%) agreed to participate in the study and were assessed 2–4 weeks (mean=25.1 days [SD=7.3]) following their child’s traumatic event involving a motor vehicle accident. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or triage category (emergency department rating of the child’s injury severity) between participants and nonparticipants, including children who could not be contacted (p>0.05).

Demographic characteristics of the 114 children (mean age=6.7 years [SD=2.7]) who participated at the 2- to 4-week assessment were as follows: 2- to 6-year-old children, N=62; 7- to 10-year-old children, N=52; girls, N=54 (47.4%); and children who belonged to a minority ethnic group or were of mixed race, N=72 (63.2%). Forty-seven (41.2%) of these children were pedestrians who were struck by a motor vehicle, and 54 (47.4%) were passengers in a car that was involved in an accident. Six children (5.3%) were involved in an accident while riding a bicycle, and six (5.3%) were passengers on a bus that was involved in an accident. Only one child (0.9%) was involved in an accident while riding a moped. Participants received relatively mild injuries, with 28 (24.6%) receiving no injuries, 80 (70.2%) sustaining soft tissue injuries, and six (5.3%) sustaining some kind of fracture. Eighteen children (15.8%) were admitted to the hospital as a result of their injuries, and seven (6.1%) lost consciousness during or shortly after their accident. In the section of London where these accidents occurred, low-speed motor vehicle accidents are common as a result of the large volume of traffic.

Among the 114 families who participated in the study, 109 (95.6%) (families of 2- to 6-year-old children: N=60; families of 7- to 10-year-old children: N=49) completed a second assessment 6 months (mean=204.3 days [SD=21.2]) following the traumatic event. There were no differences between children who did and those who did not complete the 6-month follow-up with regard to sex, age, or triage category (all p values >0.10).

Measures

The primary measures were the structured interviews completed by children and their parents or caregivers at the initial assessment (for criteria based on the alternative algorithm and DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD [minus the duration criterion]) and at the 6-month follow-up (for criteria based on the alternative algorithm and DSM-IV PTSD). Parents completed the PTSD Semi-Structured Interview and Observational Record for Infants and Young Children (14 – 16 , 19) . This measure was used to derive the diagnosis of PTSD based on criteria from the alternative algorithm per parent report. The PTSD Semi-Structured Interview and Observational Record for Infants and Young Children possesses good interrater reliability (14) .

In order to derive a diagnosis of DSM-IV PTSD from parent report, parents also completed the PTSD schedule of the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule—Child and Parent Versions (30) . The Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule—Child and Parent Versions is a structured interview assessment of anxiety disorders in children, with excellent test-retest reliability (31) . In addition, previously developed dissociation items (26 , 32) were included at the initial assessment (2–4 weeks following the trauma) in order to derive a diagnosis of DSM-IV acute stress disorder from parent report.

The vast majority of children in the 7- to 10-year-old age range (2- to 4-week assessment: N=48 [92.3%]; 6-month follow-up: N=45 [91.8%]) completed the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale—Child and Adolescent Version (33) . The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale—Child and Adolescent Version is a well-validated structured interview that assesses PTSD from child-reported symptoms. The scale measures both the frequency and intensity of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms reported by children. (In our study, one child struggled with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale—Child and Adolescent Version and completed the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule—Child and Parent Versions instead.) At the initial assessment, additional interview items (32) were included in order to derive a diagnosis of DSM-IV acute stress disorder from child report. A diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD per child report was established based on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale—Child and Adolescent Version scores, with application of the appropriate symptom counts algorithm.

For all interview measures, the assessed impairment of functioning was explicitly associated with symptoms that were endorsed for a particular diagnosis.

For parent report interviews, the Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale (34) was used to examine convergent validity. The Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale is a 21-item parent report questionnaire that assesses child posttraumatic stress symptoms in 2- to 10-year-old children. The scale has good internal and test-retest reliability and can differentiate between trauma-exposed and nontrauma-exposed children.

Procedure

The parents or caregivers of children who met inclusion criteria were initially contacted via letter 2–4 days after their child’s attendance at an emergency department. They were then contacted via telephone 7–8 days following emergency department attendance in order to arrange the initial assessment (2–4 weeks following the trauma). Provisional appointments for the 6-month follow-up were made at the end of the 2- to 4-week assessment and confirmed via telephone. Assessments were then conducted 6 months posttrauma. Written informed consent from parents or caregivers and the consent of children >6 years old were required for participation in the study. Assessments took place in the child’s own home and were conducted by the first author (R.M.-S.) with the mother (85.1%), father (7.9%), grandparent (2.6%), or other caregiver (4.4%). Interrater reliability was established prestudy via blind-rated interviews of 21 children. These interviews were tape-recorded and rated by the second author (P.S.), who is a highly experienced child assessor. There was a 100% consensus on diagnostic status. At the 2- to 4-week assessment, parents answered further questions regarding their child’s accident. Additional information (e.g., degree of injury) was obtained from the various emergency departments. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Institute of Psychiatry and South London and Maudsley NHS Trust Research Ethics Committee (study no. 290/03).

Results

Prevalence and Course of Alternative Algorithm PTSD

The prevalence rates for a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria, differentiated by informant (parent, child), age group, and assessment point, are detailed in Table 1 . The prevalence rates from combined parent-child report for 7- to 10-year-old children are displayed in Table 2 . For this diagnosis, a criterion was met if either the parent or child endorsed the requisite symptoms (“or” rule). Prevalence rates ranged from 11.5% (from parent report at the 2- to 4-week assessment) to 50% (from combined parent-child report at the 2- to 4-week assessment). There were no significant changes in the prevalence rates of PTSD among 2- to 6-year old children and 7- to 10-year-old children between the initial assessment and 6-month follow-up (from parent report, child report, or combined parent-child report) (all p values >0.05). Correlations of the presence or absence of a diagnosis between the initial assessment and 6-month follow-up were significant for all diagnoses except PTSD based on child report among 7- to 10-year-old children. In addition, diagnosis stability (proportion of children diagnosed at the initial assessment who were also diagnosed at the 6-month follow-up [positive predictive value]) was generally high as well as the proportion of children not diagnosed at the initial assessment who remained diagnosis free at the 6-month follow-up (negative predictive value) ( Table 1 , Table 2[35] ).

Prevalence and Course of DSM-IV Acute Stress Disorder and PTSD

The prevalence rates for DSM-IV acute stress disorder (at the initial assessment) and PTSD (at the 6-month follow-up), differentiated by informant (parent, child) and age group, are displayed in Table 2 and Table 3 . In the case of parent report, the prevalence rates were uniformly low, with the highest rate being 3.9% for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder among 7- to 10-year-old children at the initial assessment. Prevalence rates for child and combined parent-child report among 7- to 10-year-old children for DSM-IV diagnoses were higher, ranging from 13.3% (PTSD from child report at the 6-month follow-up) to 29.2% (acute stress disorder from combined parent-child report at the initial assessment). To verify that the low rates for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder based on parent report at the initial assessment were not simply the result of parents failing to detect dissociation symptoms, we derived a diagnosis of PTSD based on parent report (at the initial assessment) according to DSM-IV criteria minus the duration mandate ( Table 3 ). The results revealed that the prevalence rates for PTSD from parent report were even lower than the rates for acute stress disorder from parent report at the initial assessment.

Comparisons between a DSM-IV diagnosis of acute stress disorder at the initial assessment and a DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD at the 6-month follow-up revealed no significant differences in the proportion of children with a positive diagnosis across time points, regardless of age range and informant (child, parent) and despite the different symptom profiles for acute stress disorder and PTSD. Only diagnoses (presence or absence) from child and combined parent-child report among 7- to 10-year-old children were significantly correlated across time points. In addition, diagnosis stability was poor, with the exception of combined parent-child report ( Table 2 , Table 3 ).

To investigate whether prevalence rates at the 6-month follow-up were higher for a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria than the rates for a diagnosis of PTSD based on DSM-IV criteria as a result of the former algorithm requiring fewer endorsed symptoms, we examined the mean number of symptoms for positive cases of each diagnosis (split by informant [child, parent]). There were no significant differences in symptom number for the majority of diagnoses based on child report (alternative algorithm PTSD: mean=9.14 [SD=1.77]; DSM-IV PTSD: mean=10.14 [SD=2.19]), parent report (alternative algorithm PTSD: mean=11.00 [SD=4.15]; DSM-IV PTSD: mean=10.00 [N=1]), or combined parent-child report (alternative algorithm PTSD: mean=11.00 [SD=3.74]; DSM-IV PTSD: mean=11.56 [SD=1.59]) (all t values <1.35, p>0.34). The only significant difference was found in a diagnosis per parent report for the 7- to 10-year-old group, in which children who were diagnosed with PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria were allocated more symptoms on average (alternative algorithm PTSD: mean=11.00 [SD=4.58]; DSM-IV PTSD: mean=7.00 [N=1]; t=2.62, df=8, p<0.05). Similar comparisons at the initial assessment were considered unwarranted, since a diagnosis of acute stress disorder requires fewer symptoms than a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria.

Construct Validity

Construct validity for diagnoses based on parent report was examined by investigating the association of these diagnoses with Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale scores. Analyses were only conducted for parents who completed this questionnaire at the initial assessment (N=82) and 6-month follow-up (N=72). Consequently, no correlation with DSM-IV PTSD based on parent report at the 6-month follow-up could be calculated, since there were no positive cases of a diagnosis of DSM-IV PTSD per parent report during this assessment period in which a parent had also completed the Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale. At the initial assessment, Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale scores were correlated with PTSD based on alternative algorithm criteria per parent report scores (r=0.52, p<0.0001) and acute stress disorder per parent report scores (r=0.41, p<0.0002). At the 6-month follow-up, Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale scores were correlated with PTSD based on alternative algorithm criteria per parent report scores (r=0.30, p<0.02).

Prediction of 6-Month Follow-Up Diagnoses

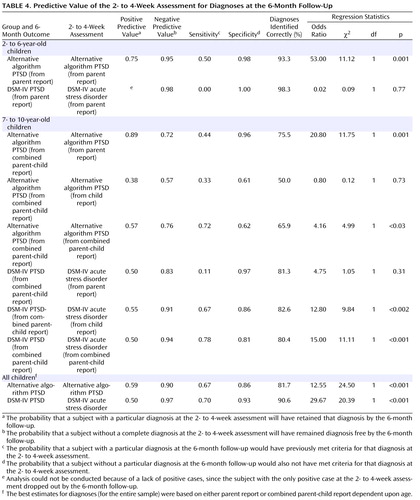

We examined the prognostic power of the various diagnoses at the initial assessment with respect to our best estimates of “true” diagnostic status at the 6-month follow-up (36) . These estimates were based on parent report for 2- to 6-year-old children and combined parent-child report for 7- to 10-year-old children. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (proportion of children diagnosed at the initial assessment who retained the diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up), and negative predictive value (proportion of children with no diagnosis at the initial assessment who remained diagnosis free at the 6-month follow-up) are reported in Table 4 . In addition, we reported the results of logistic regressions of diagnostic status at the 6-month follow-up (dependent variable) onto diagnostic status at the initial assessment (predictive variable). Since our primary objective was with regard to early detection of later diagnosis, sensitivity was a major focus in our evaluation of these data.

For 2- to 6-year-old children at the initial assessment (which is the age range for which the diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report was originally proposed [ 14 , 15 ]), a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria was only a modestly sensitive predictor of this same diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up, with 50% of cases undetected. However, this diagnosis at the initial assessment was a much better predictor of the same disgnosis at the 6-month follow-up than acute stress disorder per parent report was of DSM-IV PTSD per parent report.

For 7- to 10-year-old children, a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report at the initial assessment was a more sensitive and accurate predictor of alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report at the 6-month follow-up than was alternative algorithm PTSD per child report, in which a low positive predictive value and poorer specificity suggest that child reporters “overdetected” diagnoses at the initial assessment (diagnoses that were not present at the 6-month follow-up). However, a diagnosis of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per child or parent report resulted in more than 55% of diagnoses at the 6-month follow-up remaining undetected. Diagnoses of PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per combined parent-child report at the initial assessment were more reliable than were diagnoses based on child report alone or parent report alone, detecting nearly three-quarters of alternative algorithm PTSD based on combined parent-child report at the 6-month follow-up. However, this was at the disadvantage of relatively lower positive predictive value and specificity compared with alternative algorithm PTSD per parent report at the initial assessment, stemming from the integration of child-reported data.

For DSM-IV diagnoses among 7- to 10-year-old children, acute stress disorder based on child report at the initial assessment was a much better predictor of PTSD based on combined parent-child report at the 6-month follow-up than was acute stress disorder based on parent report. The parent-reported diagnosis failed to detect nearly 90% of the small number of 6-month follow-up cases. Similar to alternative algorithm PTSD, the best predictor was the combined parent-child report diagnosis, which provided additional sensitivity over child report alone, without any loss of specificity or positive or negative predictive value.

In our comparison of the prognostic power of alternative algorithm PTSD with that of DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD among 7- to 10-year-old children (in which both informants were available), it appeared that acute stress disorder based on combined parent-child report at the initial assessment was, overall, a better predictor of PTSD based on combined parent-child report at the 6-month follow-up than alternative algorithm PTSD based on combined parent-child report at the initial assessment was of alternative algorithm PTSD based on combined parent-child report at the 6-month follow-up. Although positive predictive value and sensitivity were similar across diagnoses, acute stress disorder based on combined parent-child report showed better negative predictive value and specificity and correctly classified more cases at the 6-month follow-up.

Parent-Child Agreement

Parent-child agreement for alternative algorithm PTSD, DSM-IV acute stress disorder, and DSM-IV PTSD among 7- to 10-year-old children is detailed in Table 5 . An inconsistent pattern was observed for individual diagnostic criteria, and agreement at the diagnostic level was poor.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined three key issues in diagnosing posttraumatic psychopathology in young children, each with broad implications for the field of developmental psychiatry. First, we sought to replicate and extend research pertaining to the validity of an alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD in young children based on parent report (14 , 15) . Second, we examined the potential complementary roles of parent and child informants in the diagnostic process (27) . Finally, we assessed and compared the predictive utility of alternative algorithm PTSD and the extant DSM-IV diagnosis for the acute posttraumatic phase (acute stress disorder) in identifying those children who are most at risk for developing later-onset alternative algorithm PTSD or the chronic phase of DSM-IV PTSD. The study benefited from 1) the use of a large untreated sample, 2) the adoption of a longitudinal design, 3) the use of formal diagnostic methods in both the acute and chronic phases, and 4) the comparison of preschool- and elementary school-age children.

Alternative Algorithm PTSD Based on Parent Report

At the 6-month follow-up, the prevalence rates for a diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report were consistent with those of existing findings (18 , 19) , with approximately 14% of subjects meeting diagnostic criteria. In contrast, the prevalence rates for the established PTSD diagnosis based on parent report was <2%. This differential pattern was similar in our assessment of both 2- to 6-year-old and 7- to 10-year-old children. The higher prevalence rates for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report for both age groups at the 6-month follow-up was not simply the result of reduced symptom requirements, since the number of symptoms endorsed for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report was not significantly less than that endorsed for DSM-IV PTSD from parent report.

In the acute posttraumatic phase (within the first month following a traumatic event), the prevalence rates for 1) alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report and 2) the standard DSM-IV diagnosis for this acute period (acute stress disorder from parent report) in 2- to 6-year-old children were 6.5% and 1.6%, respectively. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report such data for this age group. There was a similar differential pattern among 7- to 10-year-old children (alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report: 17.7%; acute stress disorder from parent report: 3.9%, respectively), which is consistent with findings at the 6-month follow-up. The higher prevalence rates for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report at the initial assessment were not simply a result of parents failing to report the requisite dissociative symptoms for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder based on parent report, since the prevalence of a diagnosis of PTSD based on parent report at the initial assessment (without the duration criterion), which does not require the presence of dissociation, was similarly low (<4%).

The diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report was stable between time points (35) , with 69% of children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retaining the diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up (positive predictive value). This finding demonstrates—for the first time—that a significant degree of psychopathology, as indexed by the alternative algorithm, persists over the first 6 months posttrauma in young children. This was not the case for the diagnosis of DSM-IV PTSD based on parent report, in which no children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retained the diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up. However, all parent report diagnoses at both the initial assessment and 6-month follow-up showed good convergent validity with the Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale.

Our data provide further support for the alternative algorithm for diagnosing PTSD based on parent report in very young children (age range: 2–6 years). These data replicate the findings of studies that used this symptom algorithm in the assessment of 2- to 6-year-old children in the acute posttraumatic phase (8 , 15) , showing the superior ability of the alternative algorithm to detect clinically significant psychopathology relative to the extant DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis. This pattern is parallel to our data regarding alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report in older children (age range: 7–10 years) and thus replicates earlier preliminary findings (8) , although with a larger sample. Our results extend the research on alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report to include the acute posttraumatic phase, providing a comparison with acute stress disorder from parent report, in which, once again, the alternative algorithm notably identified more cases relative to the standard DSM-IV algorithm. The present data also provide the first evidence of diagnostic stability for alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report during the first 6 months posttrauma in children, showing stability over a time span <2 years (cf. 19). In addition, the present study is the first to report an untreated sample of children for whom the alternative diagnostic algorithm performed favorably relative to the existing DSM-IV algorithms. Demonstrating stability in any alternative diagnostic algorithm is a key criterion of illness validity (35) and is particularly important in younger populations given the rapidity of developmental changes in these populations.

The present data, combined with previous findings on alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report (6 , 8) , are a paradigmatic illustration of the benefit of considering alternative diagnostic algorithms in diagnosing psychopathology in young children, for whom there is increasing emphasis on the need for caution in simply “down-ageing” the existing DSM taxonomy and in the application of categorical diagnosis (4 , 20) . Furthermore, the present findings indicate that alternative algorithms that are validated in very young samples of children may offer comparable (and sometimes superior) validity in older children for whom DSM diagnoses have already been established but for whom the validity of alternative algorithms has been rarely examined.

Informant Validity

For 7- to 10-year-old children in our study sample, we were able to examine the potential complementary contributions of child- and parent-reported data. At the levels of diagnoses and individual symptom clusters, parent-child agreement was generally poor for alternative algorithm PTSD and DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD, replicating previous findings for DSM-IV acute stress disorder and PTSD (28 , 37 , 38) as well as for anxiety disorders in general (39) and extending these diagnoses—for the first time—to alternative algorithm PTSD. These findings suggest that parents and children contributed different data to the diagnostic process (27) . According to their own reports, 35.4% of children met criteria for alternative algorithm PTSD per child report at the initial assessment, and 17.8% met criteria at the 6-month follow-up. In addition, 22.9% met criteria for acute stress disorder per child report at the initial assessment, and 13.3% met criteria for PTSD per child report at the 6-month follow-up. These child-reported prevalence rates were significantly higher than parent-reported prevalence rates. However, the diagnostic stability of the diagnosis of alternative algorithm PTSD per child report was notably lower than that for the parent report diagnosis, with only 31.3% of those who were diagnosed at the initial assessment continuing to meet criteria at the 6-month follow-up. The diagnostic stability of DSM-IV diagnoses for acute stress disorder per child report and PTSD per child report was also modest (36.4%), but markedly higher than that for the parent report diagnoses.

Relative to child and parent report alone, the use of combined parent-child report (with the “or” rule) in the assessment of 7- to 10-year-old children increased the prevalence rates in this age group. In addition, diagnostic stability using combined parent-child report was greater than that for child report alone, with more than one-half of the children who were diagnosed at the initial assessment retaining their diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up, regardless of whether criteria for DSM-IV acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report and PTSD per combined parent-child report or alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report were used.

In the assessment of 7- to 10-year-old children, both the use of child report and integration of child and parent report using the “or” rule resulted in an increased number of subjects being identified with posttraumatic psychopathology relative to parent report alone, although this led to reduced diagnostic stability for alternative algorithm PTSD. These data 1) further indicate the benefit of moving beyond single-informant diagnosis in order to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of clinical needs in the assessment of child psychopathology (27) and 2) strongly suggest that in situations in which only one informant is available (e.g., among 2- to 6-year-old children in the present study), clinically significant cases are overlooked.

Early Detection

For 2- to 6-year-old children, alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report assessed during the acute posttraumatic phase was a more sensitive predictor of 6-month follow-up diagnoses than was acute stress disorder based on parent report, although even the alternative algorithm failed to detect 50% of positive 6-month follow-up cases. Alternative algorithm PTSD from parent report was also more sensitive than alternative algorithm PTSD per child report in detecting diagnoses among 7- to 10-year-old children, with the latter diagnosis only identifying one-third of positive 6-month follow-up cases. However, for existing DSM-IV diagnoses, the opposite pattern was observed among 7- to 10-year-old children, with acute stress disorder per child report being a more sensitive predictor (detecting 67% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up) than was acute stress disorder from parent report (detecting 11% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up).

Combined parent-child report diagnoses were superior predictors relative to diagnoses based on parent or child report alone, with both alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report and DSM-IV acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report detecting >70% of positive cases at the 6-month follow-up. In the case of acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report, positive predictive value and specificity were comparable with the best single-informant diagnosis (acute stress disorder per child report). However, this was not the case for alternative algorithm PTSD from combined parent-child report, for which the superior sensitivity was associated with markedly lower positive predictive value and specificity relative to the best single-informant diagnosis (PTSD from parent report). This appears to have been the result of the influence of integrated child-reported data, which suggests an “overdetection” by children of diagnoses at the initial assessment (which were not subsequent diagnoses at the 6-month follow-up).

In summary, these patterns indicate that in the assessment of preschool-age children, for whom parent report alone is used, alternative algorithm PTSD based on parent report is a better measure for early detection than acute stress disorder based on parent report, although only modestly effective. In the assessment of older elementary school-age children, for whom both parent and child can be interviewed, our data indicate that combined parent-child report is optimal and that acute stress disorder per combined parent-child report is a better measure than alternative algorithm PTSD per combined parent-child report, since it is both more sensitive (detecting nearly 80% of 6-month follow-up diagnoses) and specific.

The relatively stronger predictive data for the combined parent-child report diagnosis testifies to the importance of aggregating data across different informants. Nevertheless, the overall modest levels of specificity for full diagnoses derived using clinical interview at the initial assessment, combined with the relative difficulty in obtaining such diagnoses easily and quickly in the clinic, indicate that more research is required to develop valid and sensitive simple detection instruments—perhaps involving identification of a small number of key symptoms (24) or the use of readily administered questionnaire instruments (40) .

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the use of a sample of children who were exposed to a common single-incident stressor necessarily suggests caution in generalizing the data to survivors of more chronic trauma, such as abuse, or of large-scale natural disasters. Second, the fact that the 6-month follow-up assessment was conducted by the same assessor who conducted the initial assessment, while providing continuity, means that the 6-month follow-up assessment was not conducted blind to the initial assessment status. Last, the study would have benefited from more data regarding comorbid posttraumatic diagnoses.

In conclusion, the present study provides clear data in favor of the adoption of the alternative algorithm criteria for PTSD based on parent report in the assessment of psychopathology among 2- to 6-year-old children, replacing the established DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. For this age group, PTSD based on the alternative algorithm criteria per parent report identified more cases of posttraumatic psychopathology—not simply because it requires a lower symptom count—and showed better predictive validity and stability over a 6-month period. However, for 7- to 10-year-old children, our aggregate findings between informants suggest that (assuming that parent- and child-reported data are available) the alternative algorithm does not offer a clear advantage over the established DSM-IV diagnoses for acute stress disorder and PTSD based on combined parent-child report. Thus, there is not compelling evidence in this older age group to relinquish the established DSM-IV diagnoses.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

2. Angold A, Egger HL: Preschool psychopathology: lessons for the lifespan. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:961–966Google Scholar

3. Sterba S, Egger HL, Angold A: Diagnostic specificity and nonspecificity in the dimensions of preschool psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:1005–1013Google Scholar

4. Pine DS, Alegria M, Cook EH Jr, Costello EJ, Dahl RE, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Reiss AL, Vitiello B: Advances in developmental science and DSM-V, in A Research Agenda for DSM-V. Edited by Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002, pp 85–122Google Scholar

5. Egger HL, Angold A: Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47:313–337Google Scholar

6. Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria, Infancy and Preschool: Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: the process and empirical support. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1504–1512Google Scholar

7. Andrews G, Slade T, Sunderland M, Anderson T: Issues for DSM-V: simplifying DSM-IV to enhance utility: the case of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1784–1785Google Scholar

8. Scheeringa MS, Wright MJ, Hunt JP, Zeanah CH: Factors affecting the diagnosis and prediction of PTSD symptomatology in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:644–651Google Scholar

9. Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns H, Dawson N, Sobel H, Isaacs C: Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:204–214Google Scholar

10. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:617–627Google Scholar

12. Cuffe SP, Addy CL, Garrison CZ, Waller JL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Chilappagari S: Prevalence of PTSD in a community sample of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:147–154Google Scholar

13. Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Lefkowitz ES, Pakiz B, Frost AK: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a community population of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:369–377Google Scholar

14. Scheeringa MS, Peebles CD, Cook CA, Zeanah CH: Toward establishing procedural, criterion, and discriminant validity for PTSD in early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:52–60Google Scholar

15. Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW: New findings on alternative criteria for PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:561–570Google Scholar

16. Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Drell MJ, Larrieu JA: Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:191–200Google Scholar

17. Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes LC, Gershon A, Weizman R, Cohen DJ: Israeli preschool children under scuds: a 30-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:349–356Google Scholar

18. Ohmi H, Kojima S, Awai Y, Kamata S, Sasaki K, Tanaka Y, Mochizuki Y, Hirooka K, Hata A: Post-traumatic stress disorder in pre-school aged children after a gas explosion. Eur J Pediatr 2002; 161:643–648Google Scholar

19. Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW: Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:899–906Google Scholar

20. Emde RN, Plomin R, Robinson JA, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker DW, Reznick JS, Campos J, Kagan J, Zahn-Waxler C: Temperament, emotion, and cognition at fourteen months: the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study. Child Dev 1992; 63:1437–1455Google Scholar

21. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Acute stress disorder: a synthesis and critique. Psychol Bull 2002; 128:886–902Google Scholar

22. Koopman C, Classen C, Spiegel D: Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley, Calif, firestorm. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:888–894Google Scholar

23. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S, Kirk M: Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:360–366Google Scholar

24. Dalgleish T, Meiser-Stedman R, Kassam-Adams N, Ehlers A, Winston F, Smith P, Bryant B, Mayou RA, Yule W: Is acute stress disorder the optimal means to identify child and adolescent trauma survivors at risk for later PTSD? Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192:392–393Google Scholar

25. Kassam-Adams N, Winston FK: Predicting child PTSD: the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD in injured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:403–411Google Scholar

26. Meiser-Stedman R, Yule W, Smith P, Glucksman E, Dalgleish T: Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents involved in assaults and motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1381–1383Google Scholar

27. Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ: A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1566–1577Google Scholar

28. Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P, Glucksman E, Yule W, Dalgleish T: Parent and child agreement for acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychopathology in a prospective study of children and adolescents exposed to single-event trauma. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2007; 35:191–201Google Scholar

29. Ialongo N, Edelsohn G, Werthamer-Larsson L, Crockett L, Kellam S: The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first grade children: prediction to anxious symptoms and adaptive functioning in fifth grade. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:427–437Google Scholar

30. Silverman WK, Albano AM: Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Interview Schedule. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

31. Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA: Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:937–944Google Scholar

32. Meiser-Stedman R, Dalgleish T, Smith P, Yule W, Glucksman E: Diagnostic, demographic, memory quality, and cognitive variables associated with acute stress disorder in children and adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 2007; 116:65–79Google Scholar

33. Nader K, Kriegler JA, Blake DD, Pynoos RS, Newman E, Weather FW: Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, Child and Adolescent Version. White River Junction, Vt, National Center for PTSD, 1996Google Scholar

34. Saylor CF, Swenson CC, Reynolds SS, Taylor M: The Pediatric Emotional Distress Scale: a brief screening measure for young children exposed to traumatic events. J Clin Child Psychol 1999; 28:70–81Google Scholar

35. Robins E, Guze SB: Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 126:983–987Google Scholar

36. Angold A, Egger H: Psychiatric diagnosis in preschool children, in Handbook of Infant, Toddler, and Preschool Mental Health Assessment. Edited by DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A. New York, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp 123–139Google Scholar

37. Dyb G, Holen A, Braenne K, Indredavik MS, Aarseth J: Parent-child discrepancy in reporting children’s post-traumatic stress reactions after a traffic accident. Nord J Psychiatry 2003; 57:339–344Google Scholar

38. Schreier H, Ladakakos C, Morabito D, Chapman L, Knudson MM: Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after mild to moderate pediatric trauma: a longitudinal examination of symptom prevalence, correlates, and parent-child symptom reporting. J Trauma 2005; 58:353–363Google Scholar

39. Grills AE, Ollendick TH: Issues in parent-child agreement: the case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2002; 5:57–83Google Scholar

40. Kassam-Adams N: The acute stress checklist for children (ASC-KIDS): development of a child self-report measure. J Trauma Stress 2006; 19:129–139Google Scholar