Social Perception as a Mediator of the Influence of Early Visual Processing on Functional Status in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The potential of social cognition as a mediator of relations between neurocognition and functional status in schizophrenia has been suggested by correlational studies that link neurocognition to social cognition or link social cognition to functional status. The authors used structural equation modeling to test more directly whether one aspect of social cognition (social perception) mediates relations between basic visual perception and functional status in patients with schizophrenia. METHOD: Seventy-five outpatients with schizophrenia were administered measures of early visual processing (computerized visual masking procedures), social perception (Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity), and functional status (Role Functioning Scale). RESULTS: Structural equation modeling supported social perception as a mediator of relations between early visual processing and functional status in schizophrenia. The mediation model indicated that early visual processing is linked to functional status through social perception, thereby supporting a significant indirect relationship. The direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status was significant in a model that did not include social perception but was not significant in the mediation model that included social perception. CONCLUSIONS: Social cognition appears to be a key determinant of functional status in schizophrenia. Using a very basic measure of visual perception, the present study found that social perception mediates the influence of early visual processing on functional status in schizophrenia.

Persons with schizophrenia experience severe and persistent impairments in functioning as well as deficits across a wide range of neurocognitive domains (1). A large literature supports both prospective and cross-sectional associations between neurocognitive and functional impairments in persons with schizophrenia (e.g., references 2–4). Investigators have suggested that intervening variables mediate this connection and that identifying such variables will help explicate a mechanism through which neurocognitive deficits would lead to functional impairment in schizophrenia (e.g., references 5–7).

One promising mediator of neurocognition and functional status in schizophrenia is social cognition. Social cognition has been defined as the ability to construct representations about others, oneself, and relations between others and oneself (8). Studies of social cognition in schizophrenia have focused on a variety of domains including social perception, emotion perception, attributional bias, and theory of mind (9, 10). We examined social perception in the present study because our previous findings suggested that it is related to early visual processing in schizophrenia patients (11). Social perception is similar to emotion perception but differs in the type of judgment required. Whereas emotion perception tasks require participants to evaluate social cues such as facial expressions, gestures, or voice tone to infer another’s mood, social perception tasks require participants to use social cues to infer precipitating situational events or varied interpersonal domains such as intimacy, status, mood state, and veracity.

The evidence for social cognition’s role as a mediator of neurocognition and functional status in schizophrenia is largely indirect. Correlational studies have supported a link between neurocognition and social cognition in schizophrenia and a link between social cognition and functional status in schizophrenia. For example, many correlational studies have supported a relationship between social cue perception (emotion perception or social perception) and aspects of neurocognition, including early visual processing (11–14), executive functioning (15), sensorimotor gating (16), verbal recognition memory (13), and visual vigilance (12, 15). Correlational studies have also supported a relationship between theory of mind skills (i.e., perspective-taking abilities) and neurocognition (17, 18). Although the association between social cognition and functional status has been studied less often, findings have supported links between social cognitive variables, such as theory of mind (18) and social cue perception (6, 19–23), and everyday functioning.

The possibility that social cognition acts as a mediator of neurocognition and functional status in schizophrenia can be tested more directly with structural equation modeling. In one recent study that applied structural equation modeling to this question, the authors concluded that social cognitive variables (social cue recognition and sequencing) mediated relations between varied aspects of neurocognition and vocational functioning (7). The authors of that study, however, did not formally test whether social cognition serves as mediator. Evidence for mediation has typically required three conditions: 1) the potential mediator is significantly correlated with the predictor variable, 2) the potential mediator is significantly correlated with the outcome variable, and 3) the relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable is significant before the introduction of the potential mediator but not significant when the potential mediator is introduced (24). Structural equation modeling software packages typically include a statistical test of mediation that confirms that the above conditions have been achieved (25, 26).

Our goal in the current study was to use structural equation modeling to examine the mediating influence of one aspect of social cognition, namely social perception, on relations between visual perception and functional status in schizophrenia. We intentionally selected a very basic aspect of neurocognition, early visual processing, to help clarify the direction of influence between constructs in the models. Although it is logically possible for the direction of influence to go from social cognition to early visual processing, we consider this model to be highly unlikely for two reasons. First, the processes we measured occur extremely early (within the first 100 msec of visual processing). Second, we have found that attention, which is likely to play a role in many aspects of social cognition, has a rather small effect on visual masking performance (27).

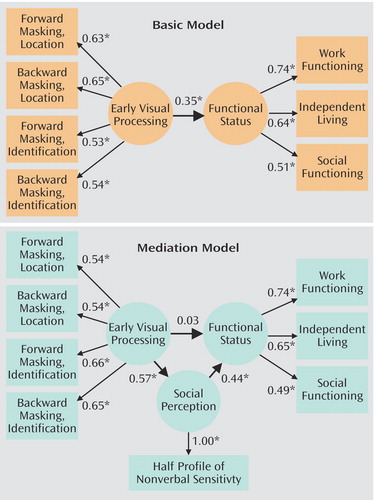

To test the hypothesis that social perception would act as a mediator of early visual processing and functional status in schizophrenia, we used two models: a basic model and a mediation model. The basic model posits only a direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status. In contrast, the mediation model posits a significant indirect relationship between early visual processing and functional status through linkages with social perception as well as a small and nonsignificant direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status. Evidence for the mediating role of social perception requires a significant indirect effect of visual processing on functional status when social perception is included in the model and a significant decrease in the relationship between visual processing and functional status from the basic model to the mediation model.

Method

Participants

Seventy-five outpatients with schizophrenia (69 male patients and six female patients) participated in the study. Participants were part of a larger National Institute of Mental Health study of early visual processing in schizophrenia (M.F. Green, principal investigator). The predominance of male patients in the study stems from that fact that most participants were recruited from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) treatment clinics. A smaller number of participants were recruited from local board-and-care facilities. All participants met the criteria for schizophrenia based on interview with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Editon (SCID-P) (28). All SCID-P interviewers were trained to administer the SCID-P in the Diagnosis and Symptom Assessment Core of the VA Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Center (MIRECC) and demonstrated agreement between their ratings and the consensus ratings of the MIRECC’s expert diagnosticians (minimum kappa coefficient of 0.80). Psychiatric symptoms were rated with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (29). All BPRS raters were trained to minimum intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.80, based on their agreement with the consensus ratings of the MIRECC’s expert diagnosticians. The BPRS ratings indicated that the outpatients were clinically stable at the time of testing (mean score for positive symptoms [conceptual disorganization, hallucination, and unusual thought content]=2.5, SD=1.3; mean score for negative symptoms [withdrawal, retardation, blunted affect, emotional withdrawal]=2.0, SD=0.9). The BPRS ratings ranged from 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe), with 4 representing the clinical threshold.

The mean age of the participants was 46.7 years (SD=9.5), participants’ mean number of years of education was 13.0 (SD=1.8), and the mean time since initial symptoms of schizophrenia was 21.2 years (SD=11.0). Fifty-one participants were taking one or more atypical antipsychotic medications, 11 participants were taking one or more typical antipsychotic medications, four participants were taking at least one atypical and at least one typical antipsychotic medication, and nine participants were taking no antipsychotic medications. After the interviews, participants were administered measures of social perception, early visual processing, and functional status during an assessment that lasted approximately 2.5 hours. The consent and recruitment procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. All participants provided their written informed consent to participate in the present study after complete description of the study procedures.

Measures

Social perception

The Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (30), which consists of the first 110 scenes of the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (31), was used to assess social perception. In nonclinical samples, the internal consistency of the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity ranges from 0.86 to 0.92, and its median test-retest reliability is 0.69 (30). The internal consistency (coefficient alpha) of the Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity for the current study group was 0.78. Scenes of this videotape-based measure last 2 seconds and contain the facial expressions, voice intonations, and/or bodily gestures of a Caucasian female. That is, each scene contains one, two, or three of these social cues. After watching each scene, the participant is asked to select which of two labels (e.g., saying a prayer, talking to a lost child) better describes a situation that would give rise to the social cue(s) observed. As in prior studies that have used the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity to assess social perception in persons with schizophrenia (e.g., references 32, 33), the administration procedure was modified in the current study to reduce the measure’s demands on sustained attention and reading comprehension. Before each scene, the videotape was paused as the experimenter read the two possible labels aloud and the participant read the labels silently from a 4-by-6-inch index card. To ensure that the participants understood the task, a practice sample of five scenes was randomly selected from the second 110 items of the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity and was administered before the scored scenes.

Early visual processing

This study was part of a larger program of research on the nature and functional implications of early visual processing deficits in schizophrenia. Computerized visual masking procedures were used to assess early visual processing. In visual masking, a brief visual masking stimulus either precedes (forward masking) or follows (backward masking) a brief visual target stimulus. The conditions have been described in previous studies from our laboratory (e.g., reference 34) and are only briefly described here. The current parameters differed from those of previous studies in two ways. First, we adapted all of the software for use with the E-Prime software program (Psychological Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh). Second, we used a monitor with a refresh rate of 160 Hz that yielded a screen refresh rate of 6.25 msec (we had previously used monitors with a refresh rate of 150 Hz).

The target stimulus was a square with a gap on one of three sides (up, down, or left) that could appear in any one of four locations (upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right) on the computer screen. It was presented for 12.5 msec. The masking stimulus was a cluster of squares that covered all possible target locations. The mask was shown for 25 msec. An initial psychophysical procedure determined the target threshold for each subject by manipulating contrast levels (described in reference 34). The threshold was set so that each subject performed at 84% accuracy with an unmasked target. Because the threshold procedure ensures that subjects can detect the unmasked target, there is no reason to exclude subjects on the basis of visual acuity. Instead, subjects were excluded if they could not achieve 84% accuracy for unmasked targets presented at the highest contrast level. All of the 75 subjects completed the threshold procedure.

For the masking conditions, 12 trials were presented for each stimulus onset asynchrony (the interval between the onset of the target and the onset of the mask), which allowed us to counterbalance the three targets and four locations. Separate forward and backward masking scores were derived for two masking conditions, yielding a total of four masking summary scores. These masking conditions were selected because they yield monotonic masking functions and are similar to the masking procedures most commonly used in studies of visual perception in schizophrenia. Briefly, the two masking conditions were:

| 1. | Target location with a high-energy mask. In this condition, participants did not need to identify the target; instead, they merely indicated which one of the four locations the target appeared. The energy of the mask was twice that of the target (four screen sweeps for the mask; two for the target). The term “energy” here refers to duration times intensity of the target. The stimulus onset asynchronies were spaced in 12.5-msec increments from –75 msec to 75 msec. In all, 12 stimulus onset asynchronies were included (the stimulus onset asynchrony of 0 was not included in this analysis). | ||||

| 2. | Target identification with a high-energy mask. In this condition, participants identified the location of the gap in the target (up, down, or left). The energy of the mask was twice the energy of the target. This condition included six forward and six backward masking intervals, ranging from –75 msec to 75 msec. The stimulus onset asynchronies were spaced in 12.5-msec increments from –75 msec to 75 msec, with additional intervals at –112.5 msec and 112.5 msec (total of 14 stimulus onset asynchronies, not including the stimulus onset asynchrony of 0). | ||||

Functional Status

The independent living skills, social functioning, and work functioning subscales of the Role Functioning Scale (35, 36) were used to assess functional status. Ratings on the three subscales were completed by one of several expert-trained interviewers after a 30-minute interview with the participant. A prior study of schizophrenia patients found that expert-trained interviewers were consistent in their Role Functioning Scale ratings (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.80) (37). The Role Functioning Scale subscale ratings range from 1 (severely impaired functioning) to 7 (optimal functioning). Each Role Functioning Scale subscale includes anchored descriptions for all seven levels of functioning that capture both the quantity and quality of the functioning in that domain.

Statistical Analyses

Structural equation modeling was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships between early visual processing, social perception, and functioning in schizophrenia. In structural equation modeling, a combination of confirmatory factor analysis and multiple regression is used to determine relations between constructs. Concerning the factor analytic properties of structural equation modeling, constructs (identified as “unobserved” or “latent” variables in structural equation modeling) are estimated by a factor analysis of data from theoretically related measures (identified as “observed” or “indicator” variables). Factor loadings are used to specify the association between an indicator variable and a latent variable. Regression analyses are used to determine the relations between the latent variables. Each association reported between two latent variables is a partial correlation with the other latent variables of the model held constant.

In the current analyses, the latent variable early visual processing was indexed with four indicator variables: forward masking for target location, backward masking for target location, forward masking for target identification, and backward masking for target identification. The variable social perception had a single indicator variable, total score on the Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity. Functional status was a latent variable with three indicator variables: scores on the independent living skills, social functioning, and work functioning subscales of the Role Functioning Scale. Two models, a basic model and a mediation model, were estimated. The basic model posits only a direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status, whereas the mediation model posits an indirect relationship between early visual processing and functional status through linkages with social perception.

Participants (N=75) were selected for these analyses if they completed the visual masking procedures. Some data were missing: 10 participants did not complete the Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity, and 11 participants did not complete the Role Functioning Scale. Analyses were performed by using three methods for handling missing data: listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, and maximum-likelihood expectation-maximization (38). The pattern of results from the three computation methods was virtually identical, so only the results obtained by using maximum-likelihood expectation-maximization are reported here.

Results

The means and standard deviations of the indicator variables are displayed in Table 1. The patients’ performance on the Half Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity was comparable to that of schizophrenia outpatients and below that of healthy participants in previous studies (11). The patients’ scores on the subscales of the Role Functioning Scale were slightly higher than those reported previously for a group of nonveteran urban schizophrenia outpatients (39). The zero-order correlations of the indicator variables are displayed in Table 2.

The basic and mediation models were estimated with the maximum likelihood solution of the EQS Structural Equation Package (40). The basic model posited only a direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status (Figure 1). The independence model, which tests whether or not the observed data fit the expected data, was readily rejected (χ2=80.33, df=21, N=75, p<0.01). The basic model provided a moderate fit for the data, as suggested by a nonsignificant chi-square (χ2=20.60, df=13, N=75, p=0.08). Because the chi-square test is very sensitive to sample size (26), two additional indices of model fit, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), were also examined (40–42). These indices also indicated that the basic model provided a moderate fit for the data (CFI=0.87, RMSEA=0.09). All indicators had moderate to high loadings on their respective latent variables. It is important to note that early visual processing predicted functional status in the basic model (standardized coefficient=0.35, p<0.05).

The mediation model was used to evaluate the strength of a direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status, as well as an indirect relationship that is mediated by social perception (Figure 1). The independence model was readily rejected (χ2=105.47, df=28, N=75, p<0.01). The mediation model provided a very good fit for the data (χ2=22.02, df=18, N=75, p=0.23, CFI=0.95, RMSEA=0.06). All indicators had moderate to high loadings on their respective latent variables. Social perception both was predicted by early visual processing (standardized coefficient=0.57, p<0.05) and was predictive of functional status (standardized coefficient=0.44, p<0.05). Stated otherwise, social perception mediated the relationship between the predictor and outcome measures, as indicated by a significant indirect path between early visual processing and functional status (standardized coefficient for indirect effect=0.25, p<0.05). It is noteworthy that the direct path from early visual processing to functional status in the mediation model was not significant (standardized coefficient=0.03, p=0.46). Early visual processing and social perception accounted for 18% of the variance in functional status.

Discussion

Structural equation modeling suggested that social perception acts as a mediator of relations between early visual processing and functional status in schizophrenia. Social perception mediated a significant indirect relationship between early visual processing and functional status. That is, the direct relationship between early visual processing and functional status, which was significant in the basic model, became nonsignificant and close to zero in the mediation model.

The present study involved only one aspect of neurocognition (early visual processing) and one aspect of social cognition (social perception), but the current finding is consistent with theoretical models that have proposed that social cognition mediates relations between neurocognition and functional status in schizophrenia (e.g., reference 5). Earlier support for social cognition’s role as a mediator in schizophrenia was largely indirect, coming mainly from correlational studies supporting either a link between neurocognition and social cognition or a link between social cognition and functional status. The current study provided a direct test of the mediating role of a social cognitive variable, social perception. The findings of this study are consistent with those of a recent study in which structural equation modeling was used but mediation was not formally tested (7), as well as the findings of a collaborating project in which path analysis was used to examine direct and indirect relationships (39).

Social cognition provides a logical mechanism through which neurocognition may influence functional status in schizophrenia. As impairments in social cognition and neurocognition likely limit community functioning (6, 9, 10), interventions that improve these domains may lead to better outcomes. Consistent with this idea, Hogarty et al. (43) recently found that an intervention that targeted neurocognition and social cognition produced long-term improvement in functional status.

Although we have theorized that neurocognition influences social cognition and functional outcome (e.g., reference 5), it remains logically possible that social cognition, or outcome variables such as social and occupational status, influence neurocognitive variables. However, a downward influence affecting early visual processing is not likely for the visual masking procedures used in the current study because they are used to assess the first 100 msec of visual perception.

In the basic model, the strength of the relationship between visual processing and functional outcome was consistent with results from other studies of neurocognition and outcome. Visual processing has only rarely been considered in previous studies of functional outcome in schizophrenia. However, studies that have included domains such as working memory, secondary memory, vigilance, and executive functioning typically report relationships with a medium effect size (e.g., r=0.30) (3), similar to what we found in this study.

The mediation model explained a moderate amount of the variance (18%) in functional outcome, and it would have been surprising if that model had explained much more, considering that it included only one aspect of social cognition and only one aspect of neurocognition. Investigation of other aspects of social cognition may contribute to our understanding of functional outcome. For example, several correlational studies have found either a link between neurocognition and theory of mind in schizophrenia or a link between theory of mind and functional status in schizophrenia (17, 18). Functioning in the community is dependent on both social cognitive skills and motivational factors such as emotional experience (anhedonia) and anticipation of interpersonal reward or rejection. Motivational factors have received less attention in the literature on schizophrenia, particularly in such models of outcome. Structural equation modeling and other modeling techniques could be used in additional studies to examine the mediating influence of multiple social cognitive and motivational variables (e.g., anhedonia). More complex models with multiple potential mediators will help to clarify the multiple determinants of functional impairment in schizophrenia.

|

|

Presented in part at the 19th annual meeting of the Society for Research in Psychopathology, St. Louis, Oct. 7–10, 2004, and at the 10th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Savannah, Ga., April 2–6, 2005. Received March 4, 2005; revision received May 22, 2005; accepted May 27, 2005. From the Department of Psychology, California State University; the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles; the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles; and the Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Sergi, Department of Psychology, California State University, 18111 Nordhoff St., Northridge, CA 91330–8255; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by NIMH grants MH-43292 and MH-65707 and by VA VISN-22 Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Center.The authors thank Jim Mintz, Ph.D., and Sun Hwang, M.S., M.P.H., for assistance with the statistical analyses.

Figure 1. Basic Model of the Relationship of Early Visual Processing and Functional Status in Schizophrenia and Mediation Model Showing Social Perception as a Mediator of the Relationshipa

aRectangles represent observed variables. Circles represent unobserved latent variables. Numbers on single-headed arrows indicate standardized regression weights.

*p<0.05, multiple regression analysis.

1. Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KR: Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:426–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Link, Google Scholar

3. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:119–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK: Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res 2004; 72:41–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH: Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:309–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kee KS, Green MF, Mintz J, Brekke J: Is emotion processing a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:487–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Vauth R, Rusch N, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW: Does social cognition influence the relation between neurocognitive deficits and vocational functioning in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Res 2004; 128:155–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Adolphs R: The neurobiology of social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2001; 11:231–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Penn DL, Corrigan PW, Bentall RP, Racenstein JM, Newman L: Social cognition in schizophrenia. Psychol Bull 1997; 121:114–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Perkins DO, Lieberman J: Implications for the neural basis of social cognition for the study of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:815–824Link, Google Scholar

11. Sergi MJ, Green MF: Social perception and early visual processing in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 59:233–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Addington J, Addington D: Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 1998; 32:171–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Corrigan PW, Green MF, Toomey R: Cognitive correlates to social cue perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1994; 53:141–151Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kee KS, Kern RS, Green MF: Perception of emotion and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: what’s the link? Psychiatry Res 1998; 81:57–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bryson G, Bell M, Lysaker P: Affect recognition in schizophrenia: a function of global impairment or a specific cognitive deficit. Psychiatry Res 1997; 71:105–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wynn JK, Sergi MJ, Dawson, ME, Schell AM, Green MF: Sensorimotor gating, orienting and social perception in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2005; 73:319–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Greig TC, Bryson GJ, Bell MD: Theory of mind performance in schizophrenia: diagnostic, symptom, and neuropsychological correlates. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:12–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Roncone R, Falloon IRH, Mazza M, De Risio A, Pollice R, Necozione S, Morosini P, Casacchia M: Is theory of mind in schizophrenia more strongly associated with clinical and social functioning than with neurocognitive deficits? Psychopathology 2002; 35:280–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Corrigan PW, Toomey R: Interpersonal problem solving and information processing deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:395–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hooker C, Park S: Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res 2002; 112:41–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mueser KT, Doonan R, Penn DL, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Nishith P, DeLeon J: Emotion recognition and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:271–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Penn DL, Spaulding W, Reed D, Sullivan M: The relationship of social cognition to ward behavior in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1996; 20:327–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Penn DL, Ritchie M, Francis J, Combs D, Martin J: Social perception in schizophrenia: the role of context. Psychiatry Res 2002; 109:149–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51:1173–1182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bentler PM: EQS: Structural Equations Program Model. Los Angeles, BMDP Statistical Software, 1996Google Scholar

26. Ullman JB: Structural equation modeling, in Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th Ed. Edited by Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 2001, pp 653-771Google Scholar

27. Rassovsky Y, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Mintz J: Modulation of attention during visual masking in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1533–1535Link, Google Scholar

28. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1997Google Scholar

29. Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, Liberman RP: Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: “the drift busters.” Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1993; 3:221–244Google Scholar

30. Ambady N, Hallahan M, Rosenthal R: On judging and being judged accurately in zero-acquaintance situations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995; 69:519–529Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Rosenthal R, Hall JA, DiMatteo MR, Rogers PL, Archer D: Sensitivity to Nonverbal Communication: The PONS Test. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979Google Scholar

32. Monti PM, Fingeret AL: Social perception and communication skills among schizophrenics and nonschizophrenics. J Clin Psychol 1987; 43:197–205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Toomey R, Wallace CJ, Corrigan PW, Schuldberg D, Green MF: Social processing correlates of nonverbal social perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry 1997; 60:292–300Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Tsuang J, Mintz J: Forward and backward masking in schizophrenia: influence of age. Psychol Med 2003; 33:887–895Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N: Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Ment Health J 1993; 29:119–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. McPheeters HL: Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two southern states. Community Ment Health J 1984; 20:44–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Brekke JS, Levin S, Wolkon GH, Sobel E, Slade E: Psychosocial functioning and subjective experience in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:599–608Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Jamshidian M, Bentler PM: ML estimation of mean and covariance structures with missing data using complete data routines. J Educ Behav Stat 1999; 24:21–41Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Brekke JS, Kay DD, Kee KS, Green MF: Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res (in press)Google Scholar

40. Bentler PM: Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 1990; 107:238–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Browne MW, Cudeck R: Alternative ways of assessing model fit, in Testing Structural Models. Edited by Bollen KA, Long JS. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1993, pp 136-162Google Scholar

42. Hu LT, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999; 6:1–55Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, Kechavan M, Cooley S, DiBarry AL, Garrett A, Parepally H, Zoretich R: Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:866–876Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar