Modulation of Attention During Visual Masking in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Schizophrenia patients consistently demonstrate performance deficits on visual masking procedures. The present study examined whether attentional manipulation would improve subjects’ performance on visual masking. METHOD: A metacontrast task was administered to 105 schizophrenia patients and 52 healthy comparison subjects. Attention was manipulated by associating selected trials of the task with monetary reward. RESULTS: Schizophrenia patients exhibited poorer performance than the comparison subjects across conditions. Patients demonstrated modest, but statistically significant, improvement in performance with the attentional manipulation. This improvement was not significant for the comparison subjects. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that early visual processes in schizophrenia are responsive to attentional manipulation but that the degree of improvement is relatively small, suggesting that these processes are not easily altered.

Visual masking procedures assess the earliest components of visual information processing (1). In visual masking, a subject’s ability to identify a visual stimulus (target) is reduced by another visual stimulus (mask) presented shortly before or after the target. Relative to healthy subjects, schizophrenia patients require longer time intervals between target and mask to identify the target (2). Despite the role of attentional deficits in schizophrenia (3), the effects of attentional manipulation on visual masking have not been explored.

The goal of the present study was to examine the effects of attentional manipulation on visual masking in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia patients and healthy comparison subjects completed a computerized masking task (4, 5). We cued attention to create a momentary enhancement of attentional allocation (i.e., increased readiness) by associating selected trials of the task with monetary reward. We predicted that cue manipulation would produce improved performance for both patients and healthy subjects.

Method

The present study included 105 schizophrenia outpatients (92% [N=97] of whom were male) and 52 nonpsychiatric comparison subjects (51% [N=27] of whom were male). The two groups are described in detail elsewhere (5). All patients were receiving antipsychotic medications (66% [N=70] were receiving second-generation antipsychotics). Mean illness chronicity was 13.6 years (SD=9.5). Patients’ average positive and negative symptom scores, according to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, were 2.58 (SD=1.22) and 2.01 (SD=0.93), respectively. All participants gave written informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the research according to procedures approved by the institutional review boards of UCLA and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

A computerized system was used to administer the masking procedures (see reference 4 for a description of masking procedures, reference 5 for description of the metacontrast procedure). Initially, we equated participants’ unmasked target identification by using a staircase method (6). During this thresholding procedure, the contrast of the target (i.e., grey scale value) was systematically adjusted on the basis of the subject’s performance to achieve 84% performance accuracy. This contrast level was used for subsequent masking procedures. A metacontrast masking procedure was used in which the mask surrounds, but does not spatially overlap, the target. The target was a square with a gap that could appear at the top, bottom, or left side (5). Targets could appear at any one of four locations on the screen (upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right). The mask was a square that surrounded all possible target areas. Stimulus onset asynchronies were spaced at 13.3-msec increments, with 24 trials administered at each stimulus onset asynchrony. On half the trials, the fixation was a small cross (standard trials); on the other half it was a star (cued trials). The fixation symbol appeared 900–100 msec before target onset. For the attentional manipulation, participants were instructed that a star indicated they would earn 5 cents if they got the next trial correct and they were paid upon session completion. Target type, location, and fixation type were randomized.

We used a factorial repeated measures analysis of variance. Diagnosis (schizophrenia versus comparison) was the between-subject factor. The within-subject design was a two-by-nine (standard versus cued trials by stimulus onset asynchrony) factorial. Primary interest focused on the interaction of diagnosis (schizophrenia versus comparison) and reward (standard versus cued trials).

Results

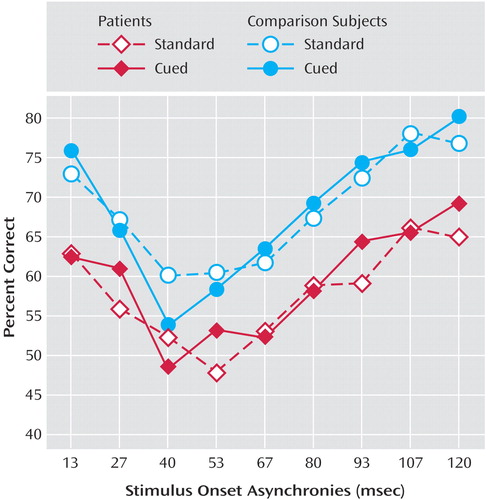

Analyses revealed a significant main effect for diagnosis (F=16.59, df=1, 155, p<0.0001), indicating that patients exhibited poorer performance than the comparison subjects during both standard and cued conditions. Patients demonstrated modest, but statistically significant, improvement in performance with the cuing (Figure 1). This improvement was not significant for the comparison subjects. The stimulus onset asynchrony-by-reward interaction was also significant for the schizophrenia patients (F=3.78, df=8, 832, p<0.0002) but not for the comparison subjects. We found a significant main effect for stimulus onset asynchrony (F=81.13, df=8, 1240, p<0.0001) but no significant diagnosis-by-reward interaction.

Discussion

Relative to the comparison subjects, patients exhibited poorer performance during both standard and cued conditions of a metacontrast procedure. Schizophrenia patients demonstrated modest, but statistically significant, improvement in performance with cuing. The improvement was not significant for the comparison subjects. The nonsignificant diagnosis-by-reward interaction indicated that the magnitude of patients’ improvement with cuing was not significantly greater than that of the comparison subjects. The fluctuating pattern of performance across stimulus onset asynchronies is likely a reflection of cortical oscillations in the gamma range (7).

Our findings are consistent with those from a study that examined the effects of attentional enhancement on eye tracking in recent-onset schizophrenia patients (8). Yee et al. found that both schizophrenia patients and healthy comparison subjects demonstrated improved eye tracking during attentional manipulation and that the attentional enhancement effect was larger in patients than in comparison subjects. Thus, attentional manipulation in both studies appears to increase momentary allocation of attention. The fact that attentional enhancement effects are either smaller or lacking among healthy subjects in these studies may indicate that comparison subjects are already using optimized attentional allocation during these tasks.

Our results offer modest support for “top-down” influences on visual perception in patients. This suggestion is consistent with growing evidence for top-down attentional effects at the earliest levels of visual processing (9). The term “top-down influences” could refer to either the influences of attention on perception or the effect of reentrant processes. These two effects may share similar circuitry and may be closely associated. As Posner has suggested (10), attention can have an effect either by amplifying the initial feed-forward activation at a given cortical site in the visual system or by enhancing the amount of reentrant activation. Typically, reentrant processing (11) is contrasted with feed-forward processing. According to feed-forward theories, perception is thought to occur through unidirectional processing of information from lower to higher levels in the brain. Reentrant processing, on the other hand, is accomplished through iterative exchanges of neural signals among levels (11). Communication between brain areas, according to the reentrant view, occurs as ascending and descending pathways form an iterative loop so that ascending stimuli would be influenced by descending top-down activity through the iterative loop process (12).

These findings that even the earliest stages of visual information processing are responsive to attentional manipulation in patients suggest very early top-down influences on the visual system. However, given the modest improvement in performance among patients and lack of improvement among comparison subjects, the influence of attention on this particular measure appears quite limited. Top-down influences for patients with schizophrenia are likely to be greater in visual tasks that emphasize later stages or more complex stimuli.

Received April 26, 2004; revisions received Aug. 13 and Aug. 20, 2004; accepted Sept. 1, 2004. From the UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles; the UCLA Department of Psychology, Los Angeles; the University of Houston Department of Psychology, Houston, Tex.; and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Rassovsky, UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, 760 Westwood Plaza (C8-747/NPI), Los Angeles, CA 90024-1759; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants to Dr. Green (MH-43292) and Dr. Nuechterlein (MH-37705) and by the Department of Veterans Affairs, VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

Figure 1. Performance on a Visual Masking Procedure for Schizophrenia Patients and Healthy Comparison Subjects, by Condition and Stimulus Onset Asynchronya

aThe standard condition involved subjects identifying a target. For the cued condition, attention was manipulated by informing the subject that trials preceded by a star would involve monetary compensation for correct identification. A statistically significant improvement in performance with the cuing manipulation was found for the patients (F=5.81, df=1, 104, p<0.05) but not for the comparison subjects.

1. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J: Backward masking in schizophrenia and mania, I: specifying a mechanism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Braff DL, Saccuzzo DP, Geyer MA: Information processing dysfunctions in schizophrenia: studies of visual backward masking, sensorimotor gating, and habituation, in Neuropsychology, Psychophysiology, and Information Processing: Handbook of Schizophrenia, vol 5. Edited by Gruzelier JH, Zubin J, Steinhauer SR. New York, Elsevier Science, 1991, pp 303–334Google Scholar

3. Nuechterlein KH: Vigilance in schizophrenia and related disorders. Ibid, pp 397–433Google Scholar

4. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B: Development of a computerized assessment for visual masking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2002; 11:83–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rassovsky Y, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Mintz J: Paracontrast and metacontrast in schizophrenia: clarifying the mechanism for visual masking deficits. Schizophr Res 2004; 71:485–492Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wetherill GB, Levitt H: Sequential estimation of points on a psychometric function. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1965; 18:1–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Green MF, Mintz J, Salveson D, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Light GA, Braff DL: Visual masking as a probe for abnormal gamma range activity in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:1113–1119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Yee CM, Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME: A longitudinal analysis of eye tracking dysfunction and attention in recent-onset schizophrenia. Psychophysiology 1998; 35:443–451Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. O’Connor DH, Fukui MM, Pinsk MA, Kastner S: Attention modulates responses in the human lateral geniculate nucleus. Nat Neurosci 2002; 5:1203–1209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Posner MI: Attention: the mechanisms of consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91:7398–7403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Di Lollo V, Enns JT, Rensink RA: Competition for consciousness among visual events: the psychophysics of reentrant visual processes. J Exp Psychol Gen 2000; 129:481–507Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hupe JM, James AC, Payne BR, Lomber SG, Girard P, Bullier J: Cortical feedback improves discrimination between figure and background by V1, V2 and V3 neurons. Nature 1998; 394:784–787Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar