Comparison of Rapid-Cycling and Non-Rapid-Cycling Bipolar Disorder Based on Prospective Mood Ratings in 539 Outpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To detect risk factors for rapid cycling in bipolar disorder, the authors compared characteristics of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling patients both from a categorical and a dimensional perspective. METHOD: Outpatients with bipolar I disorder (N=419), bipolar II disorder (N=104), and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (N=16) were prospectively evaluated with daily mood ratings for 1 year. Subjects were classified as having rapid cycling (defined by the DSM-IV criterion of four or more manic or depressive episodes within 1 year) or not having rapid cycling, and the two groups’ demographic and retrospective and prospective illness characteristics were compared. Associated factors were also evaluated in relationship to episode frequency. RESULTS: Patients with rapid cycling (N=206; 38.2%) significantly differed from those without rapid cycling (N=333) with respect to the following independent variables: history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse, bipolar I disorder subtype, number of lifetime manic or depressive episodes, history of rapid cycling, and history of drug abuse. The prevalence of these characteristics increased progressively with episode frequency. The proportion of women was greater than the proportion of men only among patients with eight or more episodes per year. The average time spent manic/hypomanic increased as a function of episode frequency, but the average time spent depressed was comparable in patients with one episode and in those with more than one episode. Brief episodes were as frequent as full-duration DSM-IV-defined episodes. CONCLUSIONS: A number of heterogeneous risk factors were progressively associated with increasing episode frequency. Depression predominated in all bipolar disorder patients, but patients with rapid cycling were more likely to be characterized by manic features. The findings overall suggest that rapid cycling is a dimensional course specifier arbitrarily defined on a continuum of episode frequency.

In 1974, Dunner and Fieve (1) defined patients with rapid cycling as having four or more manic or depressive episodes of at least 2 weeks’ duration in the year before the study. Although subsequent studies addressed the issue of rapid cycling from the perspectives of clinical and demographic features, neurobiological dysfunction, longitudinal course, and treatment response, it remains unclear to what extent rapid cycling delineates a distinct subtype or is merely an arbitrary point on a continuum of episode frequencies.

The validity of rapid cycling as a course specifier for DSM-IV bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder was reviewed by Bauer and Whybrow (2). They supported the inclusion of rapid cycling as a course specifier despite important unresolved issues, such as the paucity of characteristics that distinguish rapid-cycling patients (only female sex emerged from most studies), the arbitrariness of the criterion of four or more mood episodes per year, and the occurrence of brief but severe episodes that appeared to be abundant in rapid cycling but were formally excluded by the DSM-IV criteria. Subsequent studies gave further support for the inclusion of brief episodes in the criteria but provided little evidence in support of the boundary of four episodes per year (3–6).

In a meta-analysis of 20 clinical studies comparing rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (6), the overall prevalence of rapid cycling in unselected research samples was 16.3%, and rapid cycling was significantly associated with female gender and the bipolar II disorder subtype. That analysis confirmed the need for prospective evaluation in a large sample, particularly to address interrelationships among risk factors (3, 7).

To address these issues, we assessed episode frequency from prospective daily mood ratings and compared retrospective and prospective illness variables in patients with a rapid-cycling and a non-rapid-cycling course. In addition to classifying rapid cycling by using the traditional definition of four or more mood episodes per year, we examined these clinical characteristics in relationship to the dimension of episode frequency in an attempt to discern an empirically based boundary for rapid cycling, if present.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were adult outpatients with DSM-IV bipolar I disorder (N=419, 77.7%), bipolar II disorder (N=104, 19.3%), and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (N=16, 3.0%) diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (8). All patients participated in the former Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network with four sites in the United States (N=88, N=104, N=86, N=73), one in the Netherlands (N=143), and two in Germany (N=28, N=17), and were enrolled from 1995 through 2000 (9). Outpatients were recruited from the participating clinics and in many cases were referred by local physicians or were self-referred from local advocacy groups; the only exclusion criterion was a current comorbid substance use disorder that was severe enough to require treatment in a specialized setting (10). Interrater reliability for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was excellent (overall kappa of 0.92) (11).

Patients received treatment according to current standards in a naturalistic fashion or in various more formal pharmacological treatment protocols also designed to match usual treatment. Patients in this study group may have been included in studies or clinical trials described in other published reports from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating sites, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patient- and clinician-rated questionnaires were used to gather data on demographic characteristics, functional status, prior illness characteristics, and psychiatric history of the parents as discussed elsewhere (9–12). The SCID was used to determine comorbid axis I diagnoses. In addition, measures of thyroid parameters were available for a subgroup of 199 patients who simultaneously participated in another study (13).

Prospective Follow-Up and Episode Frequency

The prospective course of illness was followed with the clinician-rated NIMH Life-Chart Method (14), which is used to record daily ratings of severity of manic and depressive symptoms on a 9-point graphic scale. Severity ratings were based on symptom-driven degree of functional impairment. At the baseline level (euthymia, score 0), there were neither significant mood symptoms nor functional impairment. Ratings for mania were as follows: 2.5=mild, 5=low moderate, 7.5=high moderate, and 10=severe. Depression ratings were as follows: –2.5=mild, –5=low moderate, –7.5=high moderate, and –10=severe. A patient-rated Life-Chart Method was evaluated weekly to monthly by a research clinician, who then completed the clinician-rated Life-Chart Method. The validity and reliability of this procedure have been described elsewhere (15, 16). All clinicians were repeatedly trained and showed good interrater reliability (kappa=0.82) (15).

The number of episodes in 1 year was calculated by a computer program by applying two sets of criteria to the data from the clinician-rated Life-Chart Method. First, in accordance with DSM-IV, we identified episodes by using the following minimum criteria for severity and duration: 4 days of mild ratings for hypomania, 1 week of moderate ratings or any hospitalization for mania, and 2 weeks of moderate ratings for depression. An episode terminated with any switch to the opposite polarity or after 2 months of euthymia. By using a second set of criteria, we also identified isolated severe episodes that lasted 1 or more days. The computer program calculated the number of days the patient experienced the various mood states and determined the mean level of severity of the mood episodes. Computer-calculated episode counts based on the DSM-IV criteria were compared to visually counted episodes from printed life charts in a subsample of 63 patients. The correlation between the two measures was significant for depressive episodes (r=0.77, p<0.0001) and for hypomanic, manic, and mixed episodes (r=0.99, p<0.0001).

Data for all patients with at least 1 year of uninterrupted prospective daily Life-Chart Method ratings were included in the analysis. We excluded patients who left the Network before 1 year and patients with missing daily ratings at the time of the analysis. Patients with rapid cycling were defined as those with four or more depressive, hypomanic, manic, or mixed episodes (according to the DSM-IV duration criteria) in the first year of prospective follow-up.

Data Analysis

We compared demographic and retrospective and prospective illness characteristics of patients with DSM-IV-defined rapid cycling and patients without rapid cycling. We used chi-square analyses with Yates’s corrections for dichotomous variables and independent-sample t tests for continuous variables and applied Hochberg’s adjusted Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance (17). For the multivariate analysis, logistic regression was used to examine significant independent contributions of the risk factors to rapid cycling. Variables that were significant in the univariate analyses were included in the logistic regression analysis. For risk factors that were highly intercorrelated, only one of the two factors was included in the model. Other risk factors were removed if multicollinearity was an issue in any given model.

Variables that distinguished between patients with and without rapid cycling were also evaluated for their relationship with episode frequency in the first year of prospective follow-up to reveal discontinuities indicating a potential optimal cutoff point for rapid cycling. Pearson’s product-moment correlations were used to supplement visual inspection of the curves for nonlinear relationships. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Version 9.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago).

Results

Comparison of Patients With and Without Rapid Cycling

The 539 patients with 1 year of prospective ratings included 237 men (44.0%) and 302 women (56.0%). Their mean age was 42.1 years (SD=11.5). A total of 206 (38.2%) had rapid cycling, and 333 (61.8%) did not have rapid cycling. A lifetime history of rapid cycling was reported at study entry by 264 (50.7%) of 521 patients. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the current study group did not differ from those of a larger group of 631 patients that included patients with a shorter follow-up period or incomplete ratings (12).

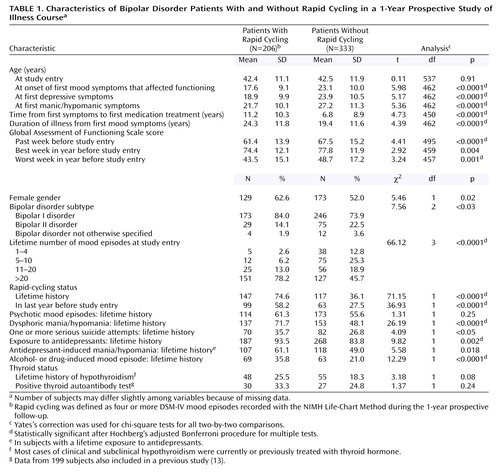

The patients’ clinical characteristics at study entry are summarized in Table 1. There was a nonsignificant overrepresentation of women in the rapid-cycling group. Educational level, marital status, and work status did not differ significantly between the groups (data not shown). Rapid cycling occurred in 41.3% of patients with bipolar I disorder and 27.9% of patients with bipolar II disorder. Patients with rapid cycling had an earlier age at onset, a longer duration of illness, and a longer time from first symptoms to first medication treatment, compared to the patients without rapid cycling. There was a strong relationship between the occurrence of rapid cycling in any prior year, in the year before study entry, and during prospective follow-up. Rapid cycling was associated with a prior history of dysphoric mania/hypomania, lifetime treatment with antidepressants, and a history of substance-induced episodes.

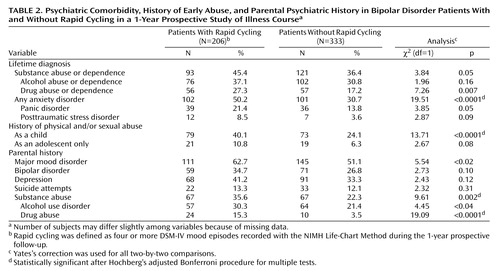

Rapid cycling was associated with lifetime DSM-IV anxiety disorder, childhood physical or sexual abuse, and parental history of drug abuse, as detailed in Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression (N=397) identified five independent variables that were significantly associated with rapid cycling: a lifetime history of rapid cycling (Wald’s χ2=17.64, df=1, p<0.0001, odds ratio=3.39), higher number of lifetime mood episodes at study entry (11–20 episodes: Wald’s χ2=5.24, df=1, p=0.02, odds ratio=4.66; >20 episodes: Wald’s χ2=8.51, df=1, p=0.004, odds ratio=6.49), bipolar I disorder subtype (Wald’s χ2=8.22, df=1, p=0.004, odds ratio=2.76), lifetime history of drug abuse (Wald’s χ2=4.57, df=1, p=0.03, odds ratio=1.99), and history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse (Wald’s χ2=4.67, df=1, p=0.03, odds ratio=1.86).

Prospective Course of Illness

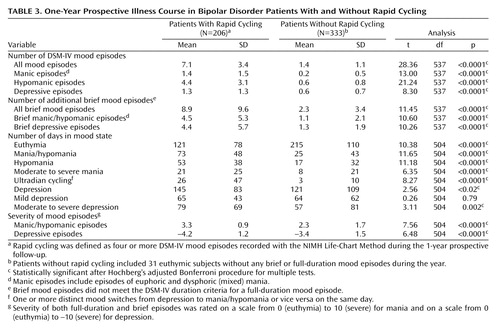

As summarized in Table 3, patients with rapid cycling had a sevenfold greater mean number of full-duration manic and hypomanic episodes and a twofold greater mean number of depressive episodes, compared to patients without rapid cycling. Over the course of the year, patients with rapid cycling spent many more days in a manic or hypomanic state than did patients without rapid cycling (73 days versus 25 days). Patients with rapid cycling also spent more days depressed, although the difference between groups was smaller (145 days versus 121 days). During follow-up, patients with rapid cycling were twice as likely to experience dysphoric mania/hypomania as were patients without rapid cycling (82.5% versus 38.1%) (χ2=99.56, df=1, p<0.0001).

Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, or lamotrigine was used alone or in combination by 193 (93.7%) of the patients with rapid cycling and 305 (91.6%) of the patients without rapid cycling. Patients with rapid cycling were more likely than those without rapid cycling to be given antidepressants (67% versus 57%) (χ2=4.60, df=1, p=0.03), antipsychotics (52% versus 32%) (χ2=19.08, df=1, p<0.00001), and thyroid hormone (32% versus 22%) (χ2=6.71, df=1, p=0.01).

Variables Related to Episode Frequency

The subjects were grouped by the number of full-duration DSM-IV episodes in the first year of prospective follow-up, as follows: no episodes (N=74) and one (N=110), two (N=78), three (N=71), four (N=46), five (N=39), six (N=24), seven (N=24), eight (N=22), nine (N=13), and 10 or more episodes (N=38).

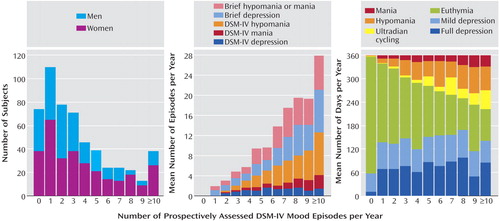

Figure 1 illustrates prospective illness characteristics in relation to overall episode frequency. Increasing episode frequency was largely attributable to manic and hypomanic episodes. The number of DSM-IV depressive episodes was relatively constant in the groups of patients with five or more full-duration DSM-IV-defined mood episodes per year. Similarly, the average number of days per year during which patients experienced hypomanic, manic, or ultradian cycling gradually increased with the number of full-duration DSM-IV-defined episodes per year, and the average number of days during which patients were depressed was relatively consistent among the groups of patients with one or more episodes per year. The number of additional brief episodes progressively increased along with the frequency of full-duration DSM-IV-defined episodes.

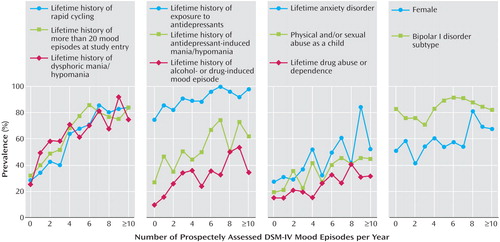

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the overall frequency of full-duration DSM-IV-defined episodes and the prevalence of the variables that distinguished patients with and without rapid cycling. Except for bipolar I disorder subtype and female gender, these variables tended to increase in prevalence as a function of episode number (r=0.15–0.37, all p<0.0001). The prevalence of bipolar I disorder subtype had a somewhat uneven pattern. An increase in the percentage of female patients at eight episodes could indicate nonlinearity; 53% of patients with zero to seven episodes were women, compared to 73% of patients with eight or more episodes (χ2=8.65, df=1, p=0.003), although the percentage of women among patients with nine and 10 or more episodes was lower than the percentage of women among patients with eight episodes. None of the other curves showed evidence of nonlinearity suggestive of this or any other cutoff point for separating patients with rapid cycling from those without rapid cycling. We reanalyzed the comparisons reported in Table 1 and Table 2 with a definition of rapid cycling as eight or more episodes; 73 subjects had rapid cycling according to this definition. Female gender was the only variable with a greater significance in the reanalysis than in the original analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first comparative investigation of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder that systematically used both a categorical and a dimensional analysis and is one of the few studies (18, 19) in which the diagnosis of rapid cycling was based on prospectively observed episode frequency.

In this group of 539 outpatients with bipolar disorder, prospective evaluation revealed a 38% prevalence of rapid cycling as defined by DSM-IV criteria. Notable findings in patients with rapid cycling were considerably greater severity and frequency of manic episodes and a greater severity of depressive episodes, compared to patients without rapid cycling. Patients with rapid cycling had as many brief mood episodes as full-duration DSM-IV episodes. However, there was a lack of clear boundaries between the patients with and without rapid cycling on any of the prospective and retrospective variables examined as a function of episode number.

The prospective course of illness indicates that the study subjects were considerably ill despite extensive treatment. The prospective illness characteristics of the 419 bipolar I disorder patients were similar to findings in a group of 146 patients with bipolar I disorder who were followed for 2–20 years in the Collaborative Depression Study (20). The patients in the Collaborative Depression Study were depressed an average of 31.9% of the time, manic for 2.3%, hypomanic for 7.0%, and cycling/mixed for 5.9%. The patients in our study experienced those mood states 35.6%, 3.9%, 8.7%, and 3.3% of the time, respectively.

These findings confirm that the main burden for a majority of patients with bipolar illness is depression (21); patients with rapid cycling were depressed 39.5% of the time, and patients without rapid cycling were depressed 33.2% of the time. It is interesting to note that in all patients (both with and without rapid cycling) who had one or more full-duration episodes per year, the average amount of time in a depressed state was fairly stable, regardless of the total number of episodes (Figure 1). In contrast, the proportion of time in a hypomanic, manic, or ultradian cycling state was significantly higher in patients with rapid cycling (27.1% of the time versus 7.7% of the time in patients without rapid cycling) and increased progressively as a function of episode frequency.

When we compared the prior illness histories of the patients with and without rapid cycling, we found that five independent variables were associated with rapid cycling in the logistic regression analysis: previous rapid cycling, a greater number of previous mood episodes, bipolar I disorder subtype, history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse, and lifetime drug abuse.

A previous history of rapid cycling and a history of more than 10 mood episodes before study entry were the strongest predictors of rapid cycling during the first year of prospective follow-up. This finding suggests that some patients have a propensity toward rapid cycling that may be expressed periodically or more continuously.

Our finding that rapid cycling was more prevalent among patients with bipolar I disorder contrasts with various reports of overrepresentation of patients with rapid cycling among bipolar II disorder patients (6). However, two large studies also failed to report a preponderance of rapid-cycling patients among patients with bipolar II disorder (22, 23).

Childhood physical or sexual abuse was associated with higher episode frequency. We previously reported that early abuse was associated with an earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder, serious suicide attempts, and comorbid drug abuse and anxiety disorders (12). These findings suggest that early traumatic experiences may contribute to a later adverse illness course.

Substance abuse is highly comorbid with bipolar disorder (11), and patients with rapid cycling may be particularly sensitive to the destabilizing properties of alcohol and drugs, as they frequently reported prior induction of depressive and manic/hypomanic episodes by these agents. Alternatively, patients with faster cycling frequencies may use these substances at a higher rate.

Several factors were associated with rapid cycling in the univariate but not in the multivariate analysis, indicating that these factors were intercorrelated with one or more of the factors mentioned earlier. As in other studies (6), we found a modest overrepresentation of women among the patients with rapid cycling, especially among those with higher episode frequencies. Our finding of a younger age at onset of bipolar disorder in patients with rapid cycling was also found in previous studies (23–25), as was our finding of a longer duration of illness in patients with rapid cycling (4, 5), although most studies reviewed found no differences (6). Our finding of a longer time between first symptoms and first medication treatment in patients with rapid cycling raises the question of whether earlier recognition and treatment might prevent or attenuate this more problematic course.

Prior histories of both dysphoric mania/hypomania and ultradian cycling were more prevalent in patients with rapid cycling than in patients without rapid cycling. These associations were confirmed during prospective follow-up, which suggests that depressive features pervade both manic and depressive phases of the illness in patients with faster cycle frequencies. Our study was not designed to evaluate the contribution of antidepressants to the development of rapid cycling. Still, 54% of patients in the study who had been treated with antidepressants reported having experienced an antidepressant-induced switch to mania/hypomania in the past, a phenomenon that has been associated with a subsequent rapid-cycling course (26).

The most rigorous studies of family history of mood disorders reported no significant differences in family history between patients with and without rapid cycling (4–6, 19, 27, 28). We found that a parental history of major mood disorder (bipolar disorder and/or depression) was more likely in patients with rapid cycling than in those without rapid cycling. More prominent was our finding of a parental history of drug abuse in patients with rapid cycling. However, rapid cycling was also associated with the occurrence of childhood adversity, which suggests that parental substance abuse and the associated environmental instability may have indirectly contributed to the risk of rapid cycling.

The results of our study must be considered in the context of several limitations. Although our study population is in many respects comparable to other groups of outpatients (10), 80% of the subjects in our study had bipolar I disorder, almost 60% reported a lifetime history of psychotic symptoms, and 38% had a rapid-cycling course. This greater overall severity of illness may restrict the generalizability of our findings. The exclusion of patients with less than 1 year of follow-up may have affected the representativeness of the study subjects. Moreover, the retrospective data on previous illness characteristics covered a period of many years and thus were susceptible to inaccuracies. An inevitable limitation is the fact that we studied the naturalistic course of treated bipolar disorder.

Despite these limitations, our findings can be used in the further conceptualization of rapid cycling in bipolar disorder, defined as the occurrence of four or more mood episodes per year (1). Kendell (29) proposed that boundaries between two clinical syndromes may be indicated by a nonlinear relationship between symptom measures and an independent variable on which the syndromes differ markedly. Like Bauer et al. (3), we found no bimodal distribution of the number of episodes per year. They reported that the proportion of women increased markedly among patients with four to eight episodes per year and even reached 100% among patients with nine or more episodes per year. We found a larger proportion of women among patients with eight or more episodes per year. However, this potential nonlinearity was not confirmed in analyses of any of the other risk factors we examined (Figure 1). Likewise, changing the boundary for rapid cycling from four to eight episodes per year did not essentially change the results of our dichotomous comparisons.

In conclusion, our overall findings suggest that rapid cycling is a dimensional course specifier with an arbitrarily defined cutoff at four episodes per year on a continuum of episode frequency seen in the naturalistic course of treated outpatients with bipolar disorder.

|

|

|

Presented at the Fifth International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, Pittsburgh, June 12–14, 2003. Received Feb. 19, 2004; revisions received May 14 and June 29, 2004; accepted Aug. 2, 2004. From Altrecht Institute for Mental Health Care and University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands; the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program and the Biological Psychiatry Branch, NIMH, Bethesda, Md.; the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; the UCLA Mood Disorders Research Program, Los Angeles; the Psychopharmacology Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati; the Mental Health Care Line and General Clinical Research Center, Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cincinnati; Psychiatrische Klinik der Ludwig-Maximilian Universität, Munich; Universitätsklinik für Psychiatrie der Universität Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Kupka, Altrecht Institute for Mental Health Care, Tolsteegsingel 2A, 3582 AC Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute. The authors thank Adriaan Honig, M.D., Ph.D., Baer Arts, M.D., Titus van Os, M.D., Ph.D., Pieternel Kölling, M.D., Herro Kraan, M.D., Ph.D., Max Sonnen, M.D., Rocco Hoekstra, M.D., Onno Habekotté, M.D., Harm-Jan Pot, M.D., Albert Blom, M.D., and Rein Holleboom, M.D., for patient recruitment and data collection in the Netherlands.

Figure 1. Gender, Mood Episode Type, and Number of Days in Mood States in 539 Outpatients With Bipolar Disorder, by Frequency of Full-Duration DSM-IV Mood Episodes Prospectively Assessed in a 1-Year Study of Illness Coursea

aThe number of subjects in each DSM-IV mood episode frequency group was as follows: no episodes (N=74) and one (N=110), two (N=78), three (N=71), four (N=46), five (N=39), six (N=24), seven (N=24), eight (N=22), nine (N=13), and 10 or more episodes (N=38).

Figure 2. Prevalence of Risk Factors for Rapid Cycling in 539 Patients With Bipolar Disorder, by Frequency of Full-Duration DSM-IV Mood Episodes Prospectively Assessed in a 1-Year Study of Illness Coursea

aThe number of subjects in each DSM-IV mood episode frequency group was as follows: no episodes (N=74) and one (N=110), two (N=78), three (N=71), four (N=46), five (N=39), six (N=24), seven (N=24), eight (N=22), nine (N=13), and 10 or more episodes (N=38).

1. Dunner DL, Fieve RR: Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:229–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bauer MS, Whybrow P: Validity of rapid cycling as a modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV, in DSM-IV Source Book, vol 2. Edited by Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Pincus HA, Ross R, First MB, Davis WW. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1996, pp 299–314Google Scholar

3. Bauer MS, Calabrese J, Dunner DL, Post R, Whybrow PC, Gyulai L, Tay LK, Younkin SR, Bynum D, Lavori P, Price AR: Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:506–515Link, Google Scholar

4. Maj M, Magliano L, Pirozzi R, Marasco C, Guarneri M: Validity of rapid cycling as a course specifier for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1015–1019Link, Google Scholar

5. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Formicola A, Tortorella A: Reliability and validity of four alternative definitions of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1421–1424Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Leverich GS, Nolen WA: Rapid and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1483–1494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

8. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition, version 2.0 (SCID-I/P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

9. Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Rush AJ, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Denicoff KD, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Kupka R, Kramlinger KG, Post RM: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, I: longitudinal methodology. J Affect Disord 2001; 67:33–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, Nolen WA, Denicoff KD, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, Rush AJ, Kupka R, Frye MA, Bickel M, Post RM: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, II: demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. J Affect Disord 2001; 67:45–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, Rochussen JR, Rush AJ, Post RM: Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:420–426Link, Google Scholar

12. Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE Jr, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Altshuler LL, Rush AJ, Kupka R, Frye MA, Autio KA, Post RM: Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:288–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Post RM, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, Keck PE Jr, Leverich GS, Rush AJ, Suppes T, Pollio C, Drexhage HA: High rate of autoimmune thyroiditis in bipolar disorder: lack of association with lithium exposure. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:305–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Leverich GS, Post RM: Life charting of affective disorders. CNS Spectr 1998; 3:21–37Google Scholar

15. Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Rush AJ, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Kupka R, Frye MA, Hatef J, Brotman MA, Post RM: Validation of the prospective NIMH Life-Chart Method (NIMH-LCM-p) for longitudinal assessment of bipolar illness. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1391–1397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Meaden PM, Daniels RE, Zajecka J: Construct validity of life chart functioning scales for use in naturalistic studies of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2000; 34:187–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hochberg Y: A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1988; 75:800–802Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Cowdry RW, Wehr TA, Zis A, Goodwin FK: Thyroid abnormalities associated with rapid cycling bipolar illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:414–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M: Rapidly cycling affective disorder: demographics, diagnosis, family history, and course. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:126–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Judd LJ, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:530–537Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, Rapport DJ, Suppes T, Shirley ER, Kimmel SE, Caban SJ: Bipolar rapid cycling: depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 14):34–41Google Scholar

22. Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lattuada E, Smeraldi E: Rapid cycling mood disorder: clinical and demographic features. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:336–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Calabrese JR, Allen MH, Thomas MR, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Shelton MD, Ketter TA, Goldberg JF, Bowden CL, Sachs GS: Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1902–1908Link, Google Scholar

24. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Rhodes LJ, Keck PE Jr, Cookson J, Anderson J, Bolden-Watson C, Asher J, Monaghan E, Zhou J: The efficacy of lamotrigine in rapid cycling and non-rapid cycling patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:953–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL: Early age at onset as a risk factor for poor outcome of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2003; 37:297–303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Koukopoulos A, Caliari B, Tundo A, Minnai G, Floris G, Reginaldi D, Tondo L: Rapid cyclers, temperament, and antidepressants. Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:249–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Nurnberger J Jr, Guroff JJ, Hamovit J, Berrettini W, Gershon E: A family study of rapid-cycling bipolar illness. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:87–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lish JD, Gyulai L, Resnick SM, Kirtland A, Amsterdam JD, Whybrow PC, Price AR: A family history study of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 1993; 48:37–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kendell RE: The choice of diagnostic criteria for biological research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:1334–1339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar