Familial Variation in Episode Frequency in Bipolar Affective Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Bipolar affective disorder is a familial illness characterized by recurrent episodes of mania and depression, but little is known about the familial nature of episode recurrence or its associated clinical features. The authors analyzed the recurrence frequency of affective episodes (episode frequency), along with associated clinical and demographic variables, in families with at least three members with a major affective disorder. METHOD: Members of 86 families ascertained through probands with bipolar affective disorder who had two or more first-degree relatives with a major affective disorder were interviewed by psychiatrists and assigned an all-sources diagnosis. Data for 407 subjects with a major affective disorder were analyzed. Episode frequency was estimated as the number of episodes of major depression, mania, and hypomania per year of illness. RESULTS: Episode frequency was smoothly distributed over the range of 0.02–20.2 episodes/year. Episode frequency was significantly correlated among relatives (r=0.56, p<0.004). Earlier age at onset, bipolar II disorder, hallucinations or delusions, alcoholism, and suicidal behavior were all more prevalent in the highest than in the lowest quartiles of episode frequency. Female gender and recurrent major depression were more prevalent in the lowest quartile. Panic disorder, substance abuse, and thyroid disease were all unrelated to episode frequency. Subjects with DSM-IV rapid cycling did not differ from other affected subjects for most of the variables tested. CONCLUSIONS: Episode frequency is a highly familial trait in bipolar affective disorder, associated with several indicators of severity, and may be useful in defining clinical subtypes of bipolar affective disorder with greater genetic liability. DSM-IV rapid cycling was not supported by these data as the best predictor of familiality or severity.

All patients with bipolar affective disorder experience recurrent episodes of major depression, mania, hypomania, or mixed states, but the frequency with which episodes recur can range from one in several years to many per day (1). As many as 20% of people with bipolar affective disorder experience rapid cycling, defined by DSM-IV as four or more affective episodes in a year (1, 2). Rapid cycling is more common in women and in people with bipolar II disorder (1, 3–5). Hypothyroidism, steroid hormones, and the use of antidepressants have been associated with rapid cycling, but these findings are controversial (6–10). Rapid cycling is just one extreme of the spectrum of episode frequency. Few studies have examined the full range of episode frequency in bipolar affective disorder.

Similarly, although bipolar affective disorder is a familial illness, the nature of episode frequency as a familial trait has not been investigated extensively (1, 11). Several studies have addressed morbid risk for bipolar disorder among the relatives of rapid-cycling probands (4, 5, 12, 13), and some studies have addressed the tendency of rapid cycling to run in families (14, 15), but we are aware of no previous studies that directly measure the familiality of episode frequency. This issue is important, because the absence of familiality could suggest that episode frequency is under the primary control of nongenetic factors. We report here an analysis of episode frequency in families ascertained for a genetic linkage study of bipolar affective disorder. We also examined the relationship between episode frequency and age at onset, suicidal behavior, psychosis, panic disorder, alcoholism, substance abuse, and thyroid disease in these families. We found that episode frequency is a highly familial trait, associated with several indicators of severity, that may help define clinical subtypes of bipolar affective disorder with the greatest genetic liability.

Method

Subjects

A total of 625 subjects in 86 families ascertained for a genetic linkage study (16) were eligible for the current analysis. All study volunteers gave written informed consent after the procedures had been fully explained.

Families were ascertained through a proband with a reported history of bipolar I disorder and at least two first-degree relatives (at least two siblings or at least one sibling and only one parent) with a major affective disorder.

Among affected subjects, the average level of education was 14.3 years (SD=3.0), and 77.3% were employed. Twenty-six percent were married, 55.8% were separated or divorced, and the rest were widowed or never married.

Clinical Assessment

All subjects were interviewed by a psychiatrist who used the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (17). Two additional psychiatrists reviewed the interview notes, family informant data, and medical records before assigning best-estimate diagnoses under Research Diagnostic Criteria (18). The diagnosis of bipolar II disorder required recurrent major depression as well as hypomania. All diagnoses were found to be highly reliable, on the basis of assessments of co-rated and test-retest interviews, as well as agreement between the psychiatrists who provided the best-estimate diagnoses (19). Final diagnoses among the probands were as follows: bipolar I disorder, N=71; bipolar II disorder, N=12; and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, N=3. In the total study group of probands and their family members, 23.0% (N=144) had bipolar I disorder, 24.2% (N=151) had bipolar II disorder, 16.2% (N=102) had recurrent unipolar depression, 1.6% (N=10) had schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, 7.0% (N=44) had an uncertain diagnosis, and 27.8% (N=174) were deemed unaffected. Of the 407 affected subjects, 64% were female.

Retrospective lifetime self-report data for several clinical variables were collected with the SADS-L. This study focused on age at onset and number of episodes of mania, hypomania, and major depression, which were derived directly from the corresponding items in the SADS-L instrument. Age at onset was defined as age at first mania or major depression, whichever was earlier (20). The number of episodes was estimated by the interviewer, who worked with each subject to define in detail the most severe episode of mania, hypomania, and major depression, then asked, “How many episodes like this have you had in your lifetime?” Subjects were asked to count periods of illness separated by at least 2 months of recovery as separate episodes. Continuous periods of illness involving a switch in polarity were counted as two episodes, provided that each pole appeared to fulfill the diagnostic criteria, but these switches were uncommon.

Data were also extracted for six clinical variables that have been associated with bipolar affective disorder in the literature: alcoholism, substance abuse, panic disorder, psychosis, suicidal behavior, and thyroid disease (1). Thyroid disease data (hypo- or hyperthyroidism) were not collected during the first year of the study but were available from 312 affected and 149 unaffected subjects ascertained later.

Statistical Analysis

Episode frequency was calculated on the basis of the total reported episodes of major depression, mania, or hypomania per year of illness, as follows: episode frequency = total number of episodes of illness/(age at interview – age at onset). Five subjects with an illness duration of less than 2 years were excluded, because a small denominator may inflate the episode frequency and subjects may tend to volunteer for a study around a time of increased illness activity. Reports of mixed episodes are not elicited by the SADS-L, so data for mixed episodes are not included in this calculation. Because episode frequency showed a highly skewed distribution, the values were log-transformed.

The data were stored by using a relational database system that was based on Paradox (versions 5 and 8) (Corel Corp., Ottawa, Canada) (21).

Continuous variables were analyzed by t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), and categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Because the use of relatives’ data in the ANOVA could lead to biased estimates of variance, familiality was also assessed in a mixed-effects regression procedure in which the likelihood ratio test was used to compare the log likelihoods of “intercept-only” models and models that include family membership as a random effect (22). The mixed-effects model assumes that data within clusters are dependent (as is the case for data from relatives) and estimates the degree of dependency along with the parameters of the model.

The ANOVA was performed with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and the regression analyses were performed with MIXREG (23). The alpha level was set at 0.05. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

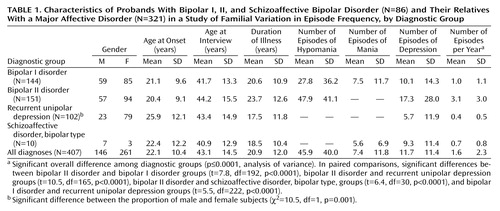

The variables used in the analysis of episode frequency, along with their relationship to gender and diagnostic group, are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences among diagnostic groups in mean age at onset, duration of illness, or gender, except for the expected higher prevalence of women in the recurrent unipolar depression group.

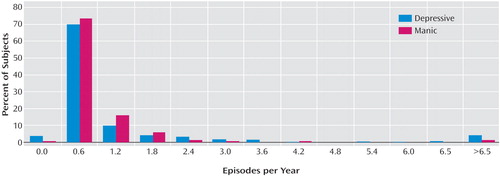

Episode frequency was smoothly distributed over the range of 0.02 to 20.2 episodes per year in this group of subjects (Figure 1). We observed no discontinuity at the DSM-IV rapid-cycling threshold of four episodes per year. The distributions were similar when depressive, manic, and hypomanic episodes were considered separately, so only the total episode frequency was considered in the subsequent analyses.

Association With Diagnostic Group

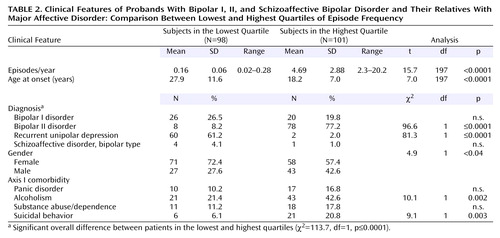

Episode frequency was significantly associated with diagnostic group (p<0.001). Specific comparisons revealed that episode frequency was highest among subjects with bipolar II disorder and lowest among subjects with recurrent unipolar depression (Bonferroni corrected p<0.001 for each of four comparisons). When subjects in the lowest and highest quartiles of episode frequency (range=0.02–0.28 episodes/year and range=2.3–20.2 episodes/year, respectively) were contrasted (Table 2), recurrent unipolar depression was more prevalent in the lowest quartile, and bipolar II disorder was more prevalent in the highest quartile (p≤0.0001).

Association With Other Variables

Gender

There was no significant difference in episode frequency between male and female subjects (t=1.39, df=403, n.s.), but subjects in the lowest quartile of episode frequency were more likely to be female (Table 2).

Age at onset

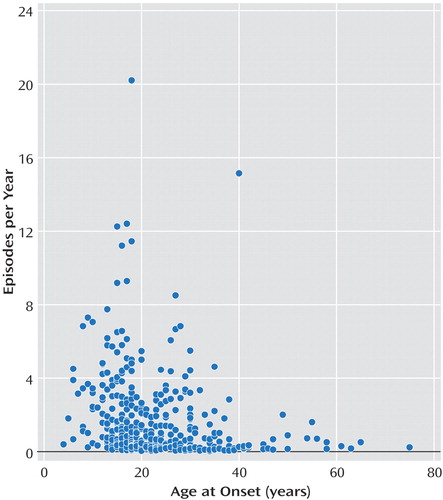

Age at onset was negatively correlated with episode frequency (r=–0.19, N=401, p<0.001). However, the relationship was not strictly linear (Figure 2). The highest episode frequencies were seen among subjects with onset between ages 15 and 18 years. Similarly, age at onset was significantly lower among those in the highest quartile of episode frequency (Table 2).

Psychosis

Psychosis, defined here as hallucinations or delusions (1), frequently complicated bipolar affective disorder in this group of subjects; 31.2% of subjects reported a history of psychosis at some time during their illness. Episode frequency was significantly higher in subjects with a history of psychosis than in those with no such history (F=5.53, df=1, 392, p<0.02).

Suicidal behavior and other axis I comorbidities

Typical patterns of suicidal behavior and comorbidity were observed in this group of subjects (1, 24, 25). Alcoholism was the most common comorbid disorder, found in 33.8% (N=136) of the subjects. Suicidal behavior was present in 20.6% (N=83), illicit substance abuse/dependence in 16.7% (N=67), and panic disorder in 11.9% (N=48).

Episode frequency was significantly associated with some but not all of these variables. Episode frequency was significantly associated with alcoholism (F=8.64, df=1, 400, p=0.003) and with a history of suicidal behavior (F=7.23, df=1, 400, p=0.007). Panic disorder and illicit substance abuse/dependence were not associated with episode frequency (F=2.49, df=1, 397, n.s., and F=2.35, df=1, 400, n.s., respectively). Similar results were observed in the quartiles analysis (Table 2), which also demonstrates the direction of each association.

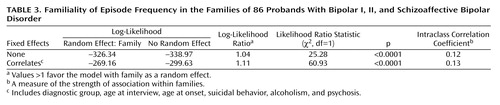

Familiality

Episode frequency was significantly correlated among probands and their affected relatives (intraclass r=0.56, F=1.53, df=96, 321, p<0.004), suggesting that more than 30% of the variance in episode frequency was accounted for by family membership.

The familiality of episode frequency was confirmed in the mixed regression analysis (Table 3), which accounted for the nonindependence of data among relatives. Episode frequency remained strongly familial when the correlated variables (diagnostic group, age at interview, age at onset, psychosis, alcoholism, and suicidal behavior) were included in the model as fixed effects. This finding showed that the familiality of episode frequency in this group of subjects was not due solely to any familial tendency of the correlated variables.

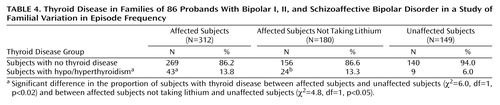

Thyroid disease comorbidity

There was no significant difference in episode frequency between subjects with thyroid disorder and those without thyroid disorder. However, 43 (13.8%) of 312 affected subjects and nine (6%) of 149 unaffected subjects reported a history of thyroid disease (Table 4). A similar proportion of affected subjects who were exposed to lithium (19 [14.3%] of 132) and affected subjects who were not exposed to lithium (24 [13.3%] of 180) reported thyroid disease, and both of those groups were significantly more likely to report thyroid disease than were the unaffected subjects (p<0.05). The prevalence of thyroid disease is generally considered to be greater in females and to increase with age (26), but this pattern did not account for our findings. The proportion of female subjects was similar in the groups with and without thyroid disease, and the mean age at interview was lower among affected subjects with thyroid disease than among unaffected subjects (mean=46.6 years, SD=11.9, versus mean=68.5 years, SD=11.0) (t=3.9, df=30, p<0.001).

DSM-IV rapid cycling

Forty-six subjects (11.1%) met the DSM-IV criteria for rapid cycling (four or more episodes/year). These subjects were significantly more likely than those reporting fewer than four episodes/year to have a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder (87.1%) (χ2=55.2, df=1, p<0.0001). However, none of the other demographic or clinical variables analyzed in this study differed between the subjects with DSM-IV rapid cycling and the other subjects. We did not detect significant evidence that the categorical trait of rapid cycling was familial in this study group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study demonstrated for the first time that episode frequency, defined as the number of affective episodes per year, is a familial trait in bipolar affective disorder. We further showed that the familiality of episode frequency is not accounted for by other, correlated variables, such as affective diagnosis subtype, psychosis, alcoholism, or suicidal behavior. As a familial trait associated with several indicators of disease severity, episode frequency may help to define clinical subtypes of bipolar affective disorder with greater genetic liability. These data did not support DSM-IV rapid cycling as the best predictor of familiality or severity.

The data were collected from 407 subjects in 86 families, to our knowledge the largest data set ever studied for episode frequency. Diagnoses were highly reliable and were made by including all available data in a best-estimate procedure. The primary data used in estimating episode frequency were retrospective and thus subject to recall bias. There was no reason to expect, however, that relatives would be correlated in their recall bias; thus, recall bias alone cannot account for our findings. The data collection methods had other limitations. Subjects with two or more episodes of mania were not questioned in detail about all hypomanic episodes. Thus, true episode frequency was probably underestimated for subjects with bipolar I disorder. This underestimation was also unlikely to account for our main findings, because the exclusion of hypomanic episodes did not change the distribution of episode frequency in this study group. No data were collected on treatment, so it was not possible to control for potential treatment effects on episode frequency in these data.

DSM-IV defines subjects with four or more major affective episodes in a year as having rapid cycling. The published studies of rapid-cycling subjects, so defined, have not consistently detected familial aggregation (4, 5, 12–15). We found little support for the DSM-IV definition of rapid cycling in this study group. As a categorical trait, rapid cycling was not familial in this analysis, even though we found significant evidence of familiality when we considered subjects across the full range of episode frequency. Rapid cycling was associated with the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder, but it was not correlated with any of the other clinical features we examined. Our retrospective data did not allow us to identify subjects with discrete periods of rapid cycling punctuating a course of illness with few other episodes. We cannot rule out familial effects in these subjects.

The evidence linking hypothyroidism and rapid cycling is controversial. The association of hypothyroidism with major affective disorders and the presence of thyroid antibodies in patients with major affective disorders have been described in numerous publications, but the biological relationship between these two illnesses remains unclear (6–8, 10). Our data, which relied solely on subjects’ self-report, were limited by lack of information from thyroid function tests and thyroid antibodies assays. Nevertheless, the rate of reported thyroid disease among unaffected subjects (6%) appeared similar to the population rate of 5.9% (26), and the rate of reported thyroid disease among the lithium-treated subjects was similar to that reported in another study (27). Thus, we do not appear to have greatly under- or overestimated the rates of thyroid disease in these study subjects. We found, as have others, that thyroid disease was more common among affected subjects and that this difference remained significant even after subjects with a history of lithium exposure were dropped from the analysis. We found no association between thyroid disease and episode frequency in the study group, consistent with previous studies (4, 5, 28).

Alcoholism and substance abuse are known to be highly associated with major affective disorders (1, 24, 25). In a previous study that included some of the subjects also included in the present analysis, alcoholism was found to be associated with a higher rate of suicide attempts and to be clustered in a subset of families (29). The present study extended this finding by demonstrating that alcoholism and suicide attempts are both strongly associated with episode frequency. Our new results suggest that the association between alcoholism and suicidal behavior is mediated, at least in part, by an increase in episode frequency.

Episode frequency was also associated with other clinical features of bipolar affective disorder. Age at onset (itself a significant predictor of prognosis, comorbidity, and treatment response in bipolar affective disorder [30]) was strongly associated with episode frequency in this study group. We also found that episode frequency was significantly associated with psychotic features. It is possible that episode frequency accounts for some of the tendency of psychotic features to run in families with bipolar affective disorder (31, 32). An earlier analysis of a subset of these subjects indicated that episode frequency tended to increase in successive generations of a pedigree, a phenomenon known as anticipation (33). A complete analysis of anticipation is beyond the scope of the study reported here, but if anticipation were present in the current study group, it would tend to decrease the familiality of episode frequency and thus could not account for our findings.

It may come as a surprise that the highest quartile of episode frequency contained many subjects with bipolar II disorder, which is traditionally considered less severe than bipolar I disorder, as well as many subjects with early onset, psychotic features, alcoholism, and suicidal behavior, clear indicators of a severe illness. This finding is consistent with previous reports indicating more chronicity and a higher rate of comorbidity and suicidal behavior in bipolar II disorder, compared to bipolar I disorder (34, 35). These results imply that the traditional view of severity, which emphasizes mania, may be too narrow. Bipolar II disorder is in many ways more “severe” than bipolar I disorder.

These findings have implications for genetic research in bipolar affective disorder. As a quantitative trait, episode frequency may offer an alternative phenotype that would be more powerful than the categorical phenotypes typically used in genetic linkage and association studies. Episode frequency may also offer an approach to genetic heterogeneity in bipolar affective disorder, because subjects with similar episode frequencies may be more likely to share genetic determinants. Episode frequency is also associated with several indicators of disease severity. To the extent that disease severity is related to genetic liability, episode frequency may help to define clinical subtypes of bipolar affective disorder with a greater burden of genetic risk factors. However, further data concerning the heritability of episode frequency—for example, in twins—is needed before we can make confident predictions about the potential value of episode frequency as a phenotype in genetic research.

In conclusion, we found that episode frequency is a familial trait in bipolar affective disorder. These data also raise concerns about the DSM-IV definition of rapid cycling in bipolar affective disorder. We suggest that episode frequency is an important clinical feature of bipolar affective disorder, with implications for severity, comorbid conditions, and genetic research.

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 57th annual meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Philadelphia, May 16–18, 2002. Received Jan. 29, 2003; revision received June 24, 2004; accepted Aug. 2, 2004. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore; Division of Genetic Epidemiology in Psychiatry, Central Institute of Mental Health, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany; and the Unit on the Genetic Basis of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, NIMH, Bethesda, Md. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Fisfalen, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, California at 15th St., Chicago, IL 60608; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the NIMH Intramural Research Program and NIH, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Chicago Brain Research Foundation, and the Edward F. Mallinckrodt, Jr., Foundation. Additional support for family recruitment was provided by the Charles A. Dana Foundation. The authors thank Sylvia G. Simpson, Dean MacKinnon, and Melvin G. McInnis for contributing to the family evaluations, Donald Hedeker for advice on the use of MIXREG, and the family volunteers who make this work possible.

Figure 1. Number of Depressive and Manic Episodes per Year Since Onset of Major Affective Disorder in Probands With Bipolar I, II, and Schizoaffective Bipolar Disorder (N=86) and Their Relatives With Major Affective Disorder (N=321)a

aThe distribution of hypomanic episodes per year of illness was similar (data not shown).

Figure 2. Relationship of Age at Onset of Major Affective Disorder With Episode Frequency in Probands With Bipolar I, II, and Schizoaffective Bipolar Disorder (N=86) and Their Relatives With Major Affective Disorder (N=321)

1. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

2. Dunner DL, Fieve RR: Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:229–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Leibenluft E: Women with bipolar illness: clinical and research issues. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:163–173Link, Google Scholar

4. Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M: Rapidly cycling affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:126–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Nurnberger J Jr, Guroff JJ, Hamovit J, Berrettini W, Gershon E: A family study of rapid-cycling bipolar illness. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:87–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bauer MS, Whybrow PC: Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder, I: association with grade I hypothyroidism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:427–432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bartela L, Pellegrini L, Meschi M, Antonangeli L, Bogazzi F, Dell’Osso L, Pinchera A, Placidiet GF: Evaluation of thyroid function in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 1990; 34:13–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Haggerty JJ Jr, Evans DL, Golden RN, Pedersen CA, Simon JS, Nemeroff CB: The presence of antithyroid antibodies in patients with affective and nonaffective psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 27:51–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Esposito S, Prange AJ Jr, Golden RN: The thyroid axis and mood disorders: overview and future prospects. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:205–217Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kupka RW, Nolen WA, Post RM, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, Keck PE Jr, Leverich GS, Rush AJ, Suppes T, Pollio C, Drexhage HA: High rate of autoimmune thyroiditis in bipolar disorder: lack of association with lithium exposure. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:305–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Gershon ES, Hamovit J, Guroff JJ, Dibble E, Leckman JF, Sceery W, Targum SD, Nurnberger JI Jr, Goldin LR, Bunney WE Jr: A family study of schizoaffective, bipolar I, bipolar II, unipolar, and normal control probands. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:1157–1167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Maj M, Magliano L, Pirozzi R, Marasco C, Guarneri M: Validity of rapid cycling as a course specifier for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1015–1019Link, Google Scholar

13. Bauer MS, Calabrese J, Dunner DL, Post R, Whybrow PC, Gyulai L, Tay LK, Younkin SR, Bynum D, Lavori P, Price RA: Multisite data reanalysis of the validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:506–515Link, Google Scholar

14. MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Gershon E, Nurnberger JI Jr, Reich T, DePaulo JR: Rapid switching of mood in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:921–928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Gershon ES, Nurnberger JI Jr, DePaulo JR Jr: Association of rapid mood switching with panic disorder and familial panic risk in familial bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1696–1698Link, Google Scholar

16. Simpson SG, Folstein SE, Meyers DA, DePaulo JR: Assessment of lineality in bipolar I linkage studies. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1660–1665Link, Google Scholar

17. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Simpson SG, McMahon FJ, McInnis MG, MacKinnon DF, Edwin D, Folstein SE, DePaulo JR: Diagnostic reliability of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:736–740Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. McMahon FJ, Stine OC, Chase GA, Meyers DA, Simpson SG, DePaulo JR Jr: Influence of clinical subtype, sex, and lineality on age at onset of major affective disorder in a family sample. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:210–215Link, Google Scholar

21. McMahon FJ, Thomas CJ, Koskela RJ, Breschel TS, Hightower T, Rohrer N, Savino C, McInnis MG, Simpson SG, DePaulo JR: Integrating clinical and laboratory data in genetic studies of complex phenotypes: a network-based data management system. Am J Med Genet 1998; 81:248–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D: Applications of mixed-effect models in biostatistics. Sankhya Series B 2000; 62:70–103Google Scholar

23. Hedeker D, Gibbons RD: MIXREG: a computer program for mixed-effects regression analysis with autocorrelated errors. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1996; 49:229–252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, Rochussen JR, Rush AJ, Post RM: Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:420–426Link, Google Scholar

25. Feinman JA, Dunner DL: The effect of alcohol and substance abuse on the course of bipolar affective disorder. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:43–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Howell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, Braverman LE: Serum TSH, T4 and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:489–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Johnston AM, Eagles JM: Lithium-associated clinical hypothyroidism: prevalence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:336–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Post RM, Kramlinger KG, Joffe RT, Roy-Byrne PP, Rosoff A, Frye MA, Huggins T: Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder: lack of relation to hypothyroidism. Psychiatry Res 1997; 72:1–7Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Potash JB, Kane HS, Chiu Y-F, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, McInnis MG, McMahon FJ, DePaulo JR Jr: Attempted suicide and alcoholism in bipolar disorder: clinical and familial relationships. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2048–2050Link, Google Scholar

30. Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, Keller M, Leon AC, Endicott J, Schettler P, Judd L, Mueller T: The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:914–920Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Potash JB, Willour VL, Chiu Y-F, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, Pearlson GD, DePaulo JR Jr, McInnis MG: The familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1258–1264Link, Google Scholar

32. Potash JM, Chiu YF, Mackinnon DF, Miller EB, Simpson SG, McMahom FJ, McInnis MG, DePaulo JR Jr: Familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in a replication set of 69 bipolar disorder pedigrees. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2003; 116:90–97Crossref, Google Scholar

33. McInnis MG, McMahon FJ, Chase GA, Simpson SG, Ross CA, DePaulo JR Jr: Anticipation in bipolar affective disorder. Am J Hum Genet 1993; 53:385–390Medline, Google Scholar

34. Angst J, Gamma A, Sellaro R, Lavori PW, Zhang H: Recurrence of bipolar disorders and major depression: a life-long perspective. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 253:236–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Maser J, Rice JA, Solomon DA, Keller MB: The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord 2003; 73:19–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar