Implications of Childhood Trauma for Depressed Women: An Analysis of Pathways From Childhood Sexual Abuse to Deliberate Self-Harm and Revictimization

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Data from depressed women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse were used to characterize clinical features that distinguished the two groups and to examine relationships of childhood sexual abuse to lifetime deliberate self-harm and recent interpersonal violence. METHOD: One hundred twenty-five women with depressive disorders were interviewed and completed self-report questionnaires. Path analysis was used to examine relationships of several childhood and personality variables with deliberate self-harm in adulthood and recent interpersonal violence. RESULTS: Women with a childhood sexual abuse history reported more childhood physical abuse, childhood emotional abuse, and parental conflict in the home, compared to women without a childhood sexual abuse history. The two groups were similar in severity of depression, but the women with a childhood sexual abuse history were more likely to have attempted suicide and/or engaged in deliberate self-harm. The women with a history of childhood sexual abuse also became depressed earlier in life, were more likely to have panic disorder, and were more likely to report a recent assault. Path analysis confirmed the contributory role of childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and the significance of childhood physical abuse for recent interpersonal violence. CONCLUSIONS: Childhood sexual abuse is an important risk factor to identify in women with depression. Depressed women with a childhood sexual abuse history constitute a subgroup of patients who may require tailored interventions to combat both depression recurrence and harmful and self-defeating coping strategies.

Childhood sexual abuse is recognized as a key risk factor for depression, both during childhood (1) and subsequently (2). The severity of contact childhood sexual abuse is associated with higher rates of depression in adulthood (3), and a history of childhood sexual abuse often predicts a chronic course of depression in women (4). Sexually victimized children are often, although not invariably, also exposed to other adverse family conditions, as different forms of child abuse commonly co-occur (2). Child abuse tends to occur more frequently within families characterized by high “stress,” and parental conflict and domestic violence are strongly associated with the occurrence of both childhood sexual abuse and childhood physical abuse (5). Family contexts of parental neglect and childhood physical abuse may also place children at high risk of sexual abuse by perpetrators outside the home (6).

A key clinical issue is how women with depression who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse differ from those who were not exposed to childhood sexual abuse. Although women with a history of childhood sexual abuse do not appear to experience more severe depression, they do tend to become depressed at an earlier age (4, 7) and are more likely to attempt suicide and to engage in deliberate self-harm (7), compared to depressed women who were not exposed to childhood sexual abuse. Some evidence suggests that depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse have more features of borderline personality disorder (4, 7). However, there is no strong evidence that this group has more global personality dysfunction, compared to their depressed counterparts with no history of childhood sexual abuse (7).

We previously reported that depressed women who were sexually victimized as children experienced a general home environment characterized by more profuse adversity, compared to women without a history of childhood sexual abuse, and that childhood sexual abuse contributed independently to later acts of deliberate self-harm (7). Irrespective of the type of population studied, research has shown that deliberate self-harm is significantly more common among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse (8, 9). The aim of the present study was to further clarify the contributory role of childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm in a new group of women with depression. The subjects included in the present study were independent of those in our previous study (7).

Women who were sexually abused as children have also been found to be more vulnerable to adult sexual assault (10) (i.e., revictimization), compared with women without a history of childhood sexual abuse, and both childhood sexual abuse and childhood physical abuse have been associated with a higher likelihood of physical assault in adulthood, usually by an intimate partner (11). Thus, the present study also sought to examine the relevance of early abuse for subsequent abuse experiences among women with depression.

In this study, our aim was to further clarify the characteristics that distinguish depressed women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse by using data from an independent group of subjects. A confirmatory path analysis was conducted to investigate the predictive weight of different childhood conditions in contributing to two outcomes of clinical interest for this group: deliberate self-harm and recent interpersonal violence.

Method

Subjects

Written informed consent was obtained from patients after the procedure had been fully explained. The subjects were 126 female patients (mean age=37.8 years, SD=12.1, range=17–68) who were consecutively referred to the Mood Disorders Unit at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, New South Wales, Australia. A total of 122 patients fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for major depression, three for dysthymia, and one for adjustment disorder with depressed mood. The patients had been depressed for an average of 51 weeks (SD=60.8, range=2–350) at the time of the study. The study did not exclude patients with a chronic episode (>2 years duration).

Self-Report Questionnaires

Subjects completed a general questionnaire that consisted of questions on sociodemographic characteristics and stressful life events, including two questions about physical or sexual assault in the 12 months before their depression began (as a measure of recent experiences of interpersonal violence). Subjects also completed several self-report measures: the Measure of Parental Style (12), which included three subscales (“indifference,” “overcontrol,” and “abuse”); the 60-item NEO-Personality Inventory (13); and the seven-factor Temperament and Character Inventory (14), as well as a 142-item personality questionnaire that measures 15 personality styles that underlie the personality disorder diagnoses (15).

Assessment Interviews

A psychologist collected data on lifetime depressive episodes and anxiety disorders using the computerized Composite International Diagnostic Interview (16). A global parental conflict score was generated on the basis of three questions, each rated on a 3-point scale, that assessed perceived verbal abuse between parents, perceived physical violence between parents, and whether the parental relationship was generally volatile and/or disruptive to the family. A global emotional abuse score was similarly generated on the basis of three questions that assessed emotional neglect (i.e., one or both parents being distant or uncaring), excessive control, and verbal abuse from either parent (e.g., verbal aggression, humiliation).

Subjects were asked about any sexual or physical abuse experienced at or before age 16 years. Childhood sexual abuse was defined as any unwanted sexual experience (involving an older person or parent). Physical abuse was defined as any physical aggression or violence. If abuse experiences were affirmed, permission was asked to proceed with further questioning, consisting of methods more detailed than those used previously (7). Information was collected on the patient’s age when abuse first began and when it ceased, the identity of the perpetrator, and the frequency of abuse. The subject’s most serious reported incident was coded in terms of severity by using the following categories: 1) exposure (i.e., noncontact experiences such as exposure to pornography), 2) nonpenetrative sexual contact, and 3) any penetrative sexual contact (narrow childhood sexual abuse). The severity categories for childhood physical abuse were 1) some physical aggression (e.g., being shoved, knocked over), 2) non-life-threatening violence (e.g., physical aggression that either did or did not result in injury), or 3) life-threatening violence (e.g., involving an attempt on the patient’s life or severe beating). The patients were asked whether they had ever received counseling or psychotherapy for their abuse experiences before their current depressive episode. To gauge patients’ current subjective distress, they were asked to rate the degree to which they believed their childhood abuse experiences had a current effect (possible ratings ranged from “no impact” to “extreme impact”).

A psychiatrist then conducted an interview to collect data on current depressive features using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17) and to collect data on lifetime suicidal and self-injurious behaviors and lifetime alcohol and drug use. The psychiatrist rated depression severity on a 4-point scale from “not depressed” to “severely depressed.”

The psychiatrist made a variety of personality ratings, including a judgment of the extent to which the patient’s personality style was “disordered” across eight behavioral parameters and the degree of functionality across five relationship domains, both as defined by Millon (18) and described previously (7). The psychiatrist also rated the extent (on a scale from 0, “not at all,” to 5, “extreme”) to which each of 30 personality descriptors (i.e., key phrases) matched the patient’s long-term personality style. The descriptors were designed to assess 15 personality styles that underlie the personality disorder diagnoses (15) and allow a total personality style score to be created by summing scores for the 15 styles.

Path analysis

Path analysis was conducted to examine the predictive power of several childhood variables and personality dysfunction for both deliberate self-harm and recent interpersonal violence. An emotional abuse and neglect variable was created by summing the Measure of Parental Style parental indifference subscale score and the global emotional abuse score. A personality dysfunction variable was created by summing the total domain and parameter ratings made by the psychiatrist. As each rating assessed the effects of personality on general functioning and coping, the combined measure was viewed as the best overall measure of any existing personality disorder.

Results

Prevalence of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Thirty-seven (29.4%) of 126 women reported a history of childhood sexual abuse, as broadly defined to include both noncontact and contact forms of abuse. Two reported noncontact forms of sexual abuse (i.e., exposure to sexual acts/material), and all except one woman agreed to answer the set of questions about the abuse. We elected to study those women who experienced contact childhood sexual abuse for whom we had sufficient data (34/125 [27.2%]).

Characteristics of Childhood Sexual Abuse

The mean age at the first childhood sexual abuse incident was 9.8 years (SD=3.4, range=4–16). For the women who reported more than one incident (N=23), the abuse occurred over an average period of 3.5 years (SD=2.8, range=1–12). Mostly, the perpetrator was either a male relative outside of the immediate family (N=11) or another male known to the girl and her family (N=13). Less commonly, the abuser was said to be an older brother (N=3), a stepfather (N=4), the biological father (N=1), or a “stranger” (N=2). In terms of severity, 22 (65%) women described abuse constituting nonpenetrative contact, and the remaining 12 (35%) women reported narrow childhood sexual abuse. Seven (21%) women reported more than one perpetrator.

Table 1 presents the results of group comparisons for selected sociodemographic and key depression and anxiety variables. Women with a history of childhood sexual abuse did not differ from the remaining women on basic demographic variables. The groups were generally comparable on depression variables, including having an equivalent number of lifetime episodes and being currently depressed for a similar period. No between-groups differences in depression severity scores were found. Women with childhood sexual abuse had their first episode of depression somewhat earlier, and the majority (70%) of these women met the criterion for early-onset depression (onset before age 21 years), compared to less than half of the remaining women (44%). The two groups had similar lifetime prevalences of anxiety disorders, except for panic disorder. Significantly more of the childhood sexual abuse group (55.9%) received a diagnosis of panic disorder, compared with the remaining women (27.5%).

Table 2 reports data on childhood family variables and Measure of Parental Style scale scores for the two groups. Women with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported more conflict between parents (including domestic violence) and more emotional abuse by parents. A higher percentage (41%) of women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse reported being physically abused in the home, compared to the remaining women (11%). Self-reported Measure of Parental Style scores were consistent with these reports; the childhood sexual abuse group scored both mothers and fathers as both more abusive and more indifferent (i.e., less warm/caring) than did the remaining women.

Table 3 reports group comparisons of personality functioning and personality constructs as measured both by the psychiatrist’s ratings and by patients’ self-reports. The data show few between-group differences. The two groups had equivalent domain and parameter scores, indicating no difference in disordered personality functioning as rated by the psychiatrist. There was no difference between groups in the total psychiatrist-rated personality style score. When results for the personality style items were compared individually, patients with childhood sexual abuse histories had higher ratings on both the borderline and histrionic descriptors, although the differences between groups were no longer significant after adjustment for the family-wise error rate. When the groups were compared on personality style items modeled on the DSM personality disorder clusters, the groups had equivalent scores for cluster A and cluster C items, but the childhood sexual abuse group had significantly higher scores on the cluster B items. Thus, the groups did not appear to differ in severity of disordered personality functioning, only on certain personality style characteristics.

Group comparisons (Table 3) of the patients’ self-reported personality measures revealed no clear differences. No significant differences were found in group means for each of the NEO subscales. Women with childhood sexual abuse histories had higher “openness to experience” scores, but this difference became nonsignificant when a Bonferroni correction was applied. Further, there were no significant between-group differences in scores on the Temperament and Character Inventory subscales. There were no differences in group means for scores on individual personality style items, cluster scores, and the total personality style score.

As Table 4 shows, significantly more women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had attempted suicide in the past or had engaged in self-injurious behavior, both in the past and recently. When these data were pooled to include any act of self-injury or suicide attempt, the majority (82%) of the childhood sexual abuse group had either intentionally hurt themselves or attempted suicide at some time, compared to about half of the remaining women (48%). There were also differences in reported exposure to recent abuse experiences. More women with childhood sexual abuse histories (12%) than those without (2%) reported unwanted sexual contact constituting assault in the 12 months before the onset of the current depression. Similarly, the rate of reported physical abuse over that period was significantly higher for the childhood sexual abuse group (18%, compared to 6% for the remaining women).

Of those with a history of childhood sexual abuse, 11 (32%) had received counseling or therapy to address the abuse. As for the ratings of the current impact of the abuse, four (11.8%) women reported that the abuse had no impact on their adult life, three (8.8%) reported a slight impact, 13 (38.2%) reported a moderate impact, seven (20.6%) said that the abuse had a severe impact, and seven (20.6%) reported that it had an extreme impact.

Self-Harming Patients

Some within-group comparisons were conducted to compare women with childhood sexual abuse who had engaged in deliberate self-harm behaviors (N=19) with those who had never engaged in self-harm (N=15). We narrowed the definition of deliberate self-harm to include deliberate self-injury (e.g., cutting) and excluded suicide attempts, on the basis of the general recognition that self-injury and suicide attempts express different clinical problems and because deliberate self-harm does not typically suggest an individual’s wish to die. Thus, we controlled for the influence of any attempted suicide by creating such a binary variable and using it as a covariate in the following comparisons. For childhood factors, somewhat more of the self-harming subjects (53%), compared to the non-self-harming subjects (27%), experienced physical abuse in the home, but the difference was not significant (odds ratio=2.5, p=0.25). Self-harming subjects had a significantly higher score for illicit drug use (3.9, compared with 0.7 for non-self-harming subjects) (F=4.5, df=1, 33, p=0.04) and were more likely to have ever used alcohol excessively (36.8%, compared with 6.7%) (odds ratio=7.0, p=0.09). Almost all of the self-harming subjects (90%) were first depressed before age 21 years, compared to less than half (43%) of the non-self-harming subjects (odds ratio=11.8, p=0.01). It is not surprising that self-harming subjects had significantly higher psychiatrist-rated total personality style scores, compared with the non-self-harming subjects (34.2 versus 19.7) (F=5.8, df=1, 33, p=0.02). There were no differences between groups in rates of anxiety disorders.

Path Analysis

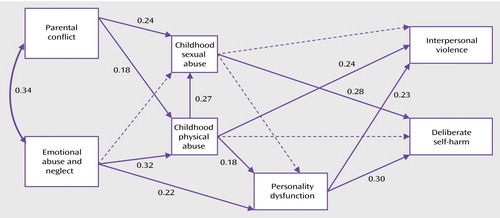

It was hypothesized that both childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse would depend on both parental conflict (i.e., conflict and domestic violence) and emotional abuse and neglect (i.e., lack of care, indifference, active verbal abuse). Figure 1 shows hypothesized pathways (i.e., all lines)—both theory-driven and data-driven—between the observed variables. The model assumed that parental conflict would be dependent on several possible unidentified factors (e.g., chronic unemployment, alcohol abuse, parental personalities). Parental conflict was considered to be a family risk factor with a relationship to both types of abuse and with a significant bidirectional relationship to emotional abuse and neglect (5). Both parental conflict and emotional abuse and neglect were considered to be vulnerability factors that heightened the risk for childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse (2). Childhood sexual abuse was also thought to be dependent to some degree on the presence of childhood physical abuse (2). It was hypothesized that personality dysfunction might be dependent on all forms of abuse directly (because of the role of childhood maltreatment in the disorganization of personality development) and that higher scores for personality dysfunction would mediate the relationship between abuse experiences and both deliberate self-harm and recent interpersonal violence. Direct pathways from childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse to both deliberate self-harm (8, 9) and recent interpersonal violence (10, 11) were also tested for the model.

The fit of the model was tested by using LISREL 8.51 (19). Path analysis indicated that the model was a good fit to the data (providing a close approximation in the study population) on the basis of goodness of fit statistics (χ2=2.08, df=6, p=0.91; root mean square error of approximation (RSMEA) = 0.00 [RSMEA confidence interval = 0.00–0.04]; comparative fit index [CFI] = 1.00; goodness of fit index [GFI] = 1.00; adjusted goodness of fit index [AGFI] = 0.98). Deletion of insignificant paths in the model (i.e., those represented by dotted lines in Figure 1) did not compromise the fit (χ2=9.52, df=10, p=0.48; RSMEA=0.00; CFI=1.00; GFI=1.00; AGFI=0.94).

Figure 1 shows the final model in which the significant paths are represented by bold lines. Both parental conflict and emotional abuse and neglect were associated with childhood physical abuse, and childhood physical abuse was associated with interpersonal violence either directly or through a mediating link with higher personality dysfunction scores. Childhood physical abuse was associated with deliberate self-harm through a mediating link either with higher personality dysfunction scores or with childhood sexual abuse. Parental conflict was directly associated with childhood sexual abuse. As expected, childhood physical abuse was directly associated with childhood sexual abuse. However, rather than finding the hypothesized direct link from emotional abuse and neglect to childhood sexual abuse, we found that childhood physical abuse mediated the link between emotional abuse and neglect and childhood sexual abuse. Childhood sexual abuse was not independently associated with the mediating variable of personality dysfunction or with interpersonal violence, but it was associated with deliberate self-harm in a direct link. High scores for emotional abuse and neglect were associated with both interpersonal violence and deliberate self-harm through a mediating link with higher personality dysfunction scores.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports (4, 7), our findings show that depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse could not be distinguished from those without a childhood sexual abuse history on the basis of depression severity, although women with childhood sexual abuse did develop depression earlier in life.

Women with a history of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to receive a diagnosis of lifetime panic disorder, compared with women without this history. This finding is consistent with research linking early trauma to adult anxiety in general and more specifically to panic disorder in women (20).

The home environment for those with a history of childhood sexual abuse was rated as more emotionally and physically abusive and as having more parental conflict. Subjects’ ratings of maternal indifference suggested that women with childhood sexual abuse held particularly strong perceptions of deprivation in maternal care.

Between-group comparisons of several personality measures identified few differences. In particular, the extent of disordered personality functioning, as measured by domain (i.e., dysfunctional relationships) and parameter (i.e., dysfunctional behaviors) ratings, did not differ between groups, which indicates that, as a group, depressed patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse were no more likely to have disordered personality functioning than depressed patients without a childhood sexual abuse history. However, patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse had higher scores on cluster B personality disorder items, which suggests that childhood trauma in the form of sexual abuse may instigate the development of phenomenology and symptoms specific to a cluster B personality picture. This relationship is not surprising, given that many features consistent with cluster B personality disorders appear early in the presentation of child sexual abuse victims (e.g., self-injury, affect dysregulation) (21). In this study, the between-group difference in scores on cluster B personality disorder items was almost entirely synonymous with the difference in prevalence of deliberate self-harm and was no longer significant after adjustment for the presence of deliberate self-harm. Given that deliberate self-harm is a diagnostic criterion for borderline personality disorder, this might offer a circular explanation as to why women with childhood sexual abuse often acquire a borderline personality disorder label or that deliberate self-harm might change the threshold for meeting disorder “caseness” criteria.

Our results demonstrate that depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse have a strong propensity toward self-damaging behaviors. Significantly more depressed women with a childhood sexual abuse history acted on self-harm impulses, compared with those who had not reported childhood sexual abuse. Almost half of the women with lifetime deliberate self-harm had a history of sexual abuse. Thus, when self-harm accompanies depression, it could be viewed as a potential indicator of childhood sexual abuse. The significantly higher rate of lifetime deliberate self-harm in women with childhood sexual abuse cannot be explained in terms of depression severity, and this higher rate constitutes strong evidence for the key relationship between childhood sexual abuse and subsequent self-harm.

We examined the data for differences between abused women who engaged in self-harm and those who did not. Some evidence for additive effects of abuse was observed, in that women with sexual abuse histories who engaged in self-harm reported more physical abuse by parents, compared to the non-self-harming group. Romans et al. (9) also found that women with childhood sexual abuse who engaged in self-harm were more likely to report childhood physical abuse and parental conflict, compared to abused women who did not report self-harm. In the current study, patients with childhood sexual abuse who reported self-harm became depressed earlier in life, compared to those who did not report self-harm, and they were also more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol. Excessive alcohol use among women with childhood sexual abuse who reported self-harm was also observed in the study by Romans et al. (9). It is noteworthy that both deliberate self-harm and drug and alcohol abuse may be perceived as “short-circuiting” strategies for diverting painful emotions (2).

These tentative results suggest that there are probably important etiological differences between childhood sexual abuse victims who later engage in deliberate self-harm and those who do not. Such differences may well relate to factors such as the age of the child at the time of the abuse, the severity of the abuse, disclosure dynamics (i.e., lack of validation) (22), or the child’s connection to the perpetrator (i.e., trust violation). Lange et al. (23) found that family reactions after disclosure of childhood sexual abuse as well as the victim’s beliefs, including self-blame, were strongly associated with subsequent distress in adults.

Path analysis confirmed that the presence of parental conflict was significantly correlated with subjects’ reports of parental emotional abuse and neglect and that these factors were linked with the two outcome variables—recent interpersonal violence and deliberate self-harm—through the presence of childhood abuse factors (childhood sexual abuse and childhood physical abuse). It is important to note that the emotional abuse and neglect measure was associated with personality difficulties, and higher scores on this measure were associated with recent sexual or physical assault and with lifetime deliberate self-harm. This finding highlights the significance of emotional abuse and neglect as important developmental factors linked with adult problems in self-definition and self-worth.

Parental conflict was significantly associated with both childhood physical abuse and childhood sexual abuse. These results support the findings from previous studies that have identified chronic parental conflict and domestic violence as key risk factors for child abuse (2). Parental conflict appears to be an important factor that renders children vulnerable to sexual abuse by perpetrators outside the home. The risk is further compounded by the high likelihood that child sex offenders target children from families with problems (6).

We found that the emotional abuse and neglect measure was not directly linked to childhood sexual abuse but was indirectly linked through the presence of childhood physical abuse. This result is consistent with our finding that most perpetrators of childhood sexual abuse were either family friends or relatives outside the home but that most physical abuse was carried out by parents. This finding adds validity to our retrospective data, in that those women who reported childhood sexual abuse did not give a “blanket” account of an emotionally bleak relationship with parents, but that such reporting was mediated by the presence of childhood physical abuse by parents. The present study found that the presence of childhood physical abuse was a key risk factor for childhood sexual abuse, a result commensurate with other evidence showing a strong correlation between childhood sexual abuse perpetrated by a non-family-member and childhood physical abuse by parents (2).

The association between childhood physical abuse and deliberate self-harm was less direct and seemed to be mediated either by the presence of childhood sexual abuse or by higher personality dysfunction scores. Path analysis confirmed that childhood sexual abuse was directly associated with deliberate self-harm and that this association required no significant mediation by high personality dysfunction scores. Path analysis demonstrated the absence of a direct relationship between childhood sexual abuse and adult victimization in the form of a sexual or physical assault in the year preceding the onset of the current depression. This finding is consistent with previous reports (22, 24) and suggests that the experience of revictimization during adulthood might be largely dependent on the presence of childhood physical abuse, either alone or in combination with childhood sexual abuse. Wind and Silvern (22) found that childhood sexual abuse was associated with revictimization in women only for women who had also experienced childhood physical abuse. In the study by Schaaf and McCanne (24), women with both childhood sexual abuse and childhood physical abuse had a higher rate of adult sexual and/or physical victimization (77%) than women with childhood physical abuse only (51%), women with childhood sexual abuse only (33%), and women with neither childhood sexual abuse nor childhood physical abuse (31%). Together, these results suggest that the presence of both types of abuse in childhood puts women at exceptionally high risk for later assaults. We recorded the occurrence of any abuse experienced by patients in a 12-month interval before their current episode of depression. The fact that we found a significant pattern of revictimization in that brief period among women with an abuse history suggests that the lifetime rate of experiencing such assaults may be relatively high in these women.

Our finding that only one-third of the women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had ever received a psychological intervention targeted at the abuse may be consistent with reports that abuse victims are more likely to somatize their distress and therefore utilize medical services rather than seek counseling (25). Alternatively, this finding might point to an inadequacy in previous treatment paradigms, particularly given the clinical characteristics of the study subjects (who had had recurrent depression from a young age), their previous contact with mental health services, and the reports by the majority of abused subjects that their abuse experiences had at least a moderate impact on their adult life. The low proportion of abused women who had received any type of abuse-focused treatment suggests a large unmet clinical need in this group of patients.

This study had some limitations that must be considered in interpreting the data. One limitation was the cross-sectional design. Gaining information about childhood sexual abuse retrospectively has advantages (e.g., immediate and comprehensive information) as well as possible disadvantages (e.g., memory biases). To minimize biases in reporting, we used a detailed interview that focused on specific circumstances. Also, although the study group comprised women with depression, the literature suggests that perception of major past events is not significantly affected by mood state and that depressed subjects’ perceptions of their parents appear to remain consistent after recovery from depression (26).

Conclusions

Women with depression who report a history of childhood sexual abuse develop depression at a younger age, are more likely to engage in deliberate self-harm behaviors and/or suicide attempts, and are more likely to experience physical or sexual assault in adulthood, compared to depressed women without childhood sexual abuse. Depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse constitute a unique subgroup that requires tailored treatment. One integrative approach includes group work programs (27) that facilitate the resolution of themes of guilt, isolation, and secrecy. The positive outcomes of such intervention programs reported in the literature (28) should encourage wider scale application of such methods.

The identification of childhood sexual abuse in patients who present with depression is important because a history of childhood sexual abuse is likely to play a key role in lowering the threshold to both onset and recurrence of depression. Early trauma that remains unresolved may further complicate recovery from a depression for which a different etiology has been ascribed and, as such, is a crucial determinant to characterize.

|

|

|

|

Received July 18, 2002; revision received July 9, 2003; accepted Dec. 4, 2003. From the School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, and the Mood Disorders Unit, Black Dog Institute, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Gladstone, The Villa, Mood Disorders Unit, Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick, NSW 2031, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by program grant 2223208 from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors thank Christine Boyd, Kay Parker, and Dusan Hadzi-Pavlovic for assistance related to this research.

Figure 1. Path Analysis of Relationships of Childhood Abuse and Personality Variables to Deliberate Self-Harm and Recent Interpersonal Violence Among Depressed Women With a History of Childhood Sexual Abusea

aAll hypothesized pathways between study variables are shown. Significant paths are indicated with solid lines labeled with path coefficients; broken lines indicate nonsignificant paths.

1. Calam R, Horne L, Glasgow D, Cox A: Psychological disturbance and child sexual abuse: a follow-up study. Child Abuse Negl 1998; 22:901–913Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bifulco A, Moran P: Wednesday’s Child: Research Into Women’s Experience of Neglect and Abuse in Childhood, and Adult Depression. London, Routledge, 1998Google Scholar

3. Cheasty M, Clare AW, Collins C: Relation between sexual abuse in childhood and adult depression: case-control study. BMJ 1998; 316:198–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Zlotnick C, Ryan CE, Miller IW, Keitner GI: Childhood abuse and recovery from major depression. Child Abuse Negl 1995; 19:1513–1516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bowen K: Child abuse and domestic violence in families of children seen for suspected sexual abuse. Clin Pediatr 2000; 39:33–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Elliott M, Browne K, Kilcoyne J: Child sexual abuse prevention: what offenders tell us. Child Abuse Negl 1995; 19:579–594Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Gladstone G, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Austin MP: Characteristics of depressed patients who report childhood sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:431–437; correction, 156:812Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Hjelmeland H: Repetition of parasuicide: a predictive study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1996; 26:395–404Medline, Google Scholar

9. Romans SE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Herbison GP, Mullen PE: Sexual abuse in childhood and deliberate self-harm. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1336–1342Link, Google Scholar

10. Russell DEH: The Secret Trauma: Incest in the Lives of Girls and Women. New York, Basic Books, 1986Google Scholar

11. Chu JA, Dill DL: Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 149:887–892Google Scholar

12. Parker G, Roussos J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Mitchell P, Austin M-P: The development of a refined measure of dysfunctional parenting and assessment of its relevance in patients with affective disorders. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1193–1203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Costa PT, McCrae RR: The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1985Google Scholar

14. Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR: A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:975–989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wilhelm K: Modeling and measuring the personality disorders. J Pers Disord 2000; 14:189–198Crossref, Google Scholar

16. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1 (CIDI-A). Sydney, Australia, WHO Research and Training Centre, 1997Google Scholar

17. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Millon T: Personality prototypes and their diagnostic criteria, in Contemporary Directions in Psychopathology: Toward the DSM-IV. Edited by Millon T, Klerman GL. New York, Guilford, 1986, pp 639–669Google Scholar

19. Joreskog KG, Sorbom D: LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling With the SIMPLIS Command Language. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993Google Scholar

20. Stein MB, Walker JR, Anderson G, Hazen AL, Ross CA, Eldridge G, Forde DR: Childhood physical and sexual abuse in patients with anxiety disorders and in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:275–277Link, Google Scholar

21. Swanston HY, Tebbutt JS, O’Toole BI, Oates KR: Sexually abused children 5 years after presentation: a case-control study. Pediatrics 1997; 100:600–608Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Wind TW, Silvern L: Parenting and family stress as mediators of long-term effects of child abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1994; 18:439–453Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Lange A, De Beurs E, Dolan C, Lachnit T, Sjollema S, Hanewald G: Long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse: objective and subjective characteristics of the abuse and psychopathology in later life. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:150–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Schaaf KK, McCanne TR: Relationship of childhood sexual, physical, and combined sexual and physical abuse to adult victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse Negl 1998; 22:1119–1133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Newman MG, Clayton L, Zuellig A, Cashman L, Arnow B, Dea R, Taylor CB: The relationship of childhood sexual abuse and depression with somatic symptoms and medical utilization. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1063–1077Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH: Psychopathology and early experience: a reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull 1993; 113:82–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Chew J: Women Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse: Healing Through Group Work. New York, Haworth Press, 1998Google Scholar

28. Gorey KM, Richter NL, Snider E: Guilt, isolation and hopelessness among female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: effectiveness of group work intervention. Child Abuse Negl 2001; 25:347–355Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar