Characteristics of Depressed Patients Who Report Childhood Sexual Abuse

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Depressed patients who had and had not been exposed to childhood sexual abuse were studied to determine differences in severity of depressed mood, lifetime histories of anxiety and depression, childhood environment, and disordered personality function. METHOD: Data were obtained from 269 inpatients and outpatients with major depression (171 women and 98 men) by means of structured clinical interviews and self-report questionnaires. RESULTS: Forty-six of the 269 patients reported childhood sexual abuse; 40 of these were women. These 40 women were compared with the 131 who did not report childhood sexual abuse. The patients who experienced abuse did not differ from those who had not on psychiatrist-rated mood severity estimates, but they did have higher self-report depression scores. They also evidenced more self-destructive behavior, more personality dysfunction, and more overall adversity in their childhood environment. Childhood sexual abuse status was associated with more borderline personality characteristics independently of other negative aspects of the patients’ earlier parenting. Childhood sexual abuse status was linked strongly to adult self-destructiveness, as was early exposure to maternal indifference. CONCLUSIONS: Multivariate analyses suggest that depression is unlikely to be a direct consequence of childhood sexual abuse. Childhood sexual abuse appears to be associated with a greater chance of having experienced a broadly dysfunctional childhood home environment, a greater chance of having a borderline personality style, and, in turn, a greater chance of experiencing depression in adulthood. (Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:431–437)

The long-term psychological sequelae of childhood sexual abuse have been pursued in clinical and nonclinical samples. Although linked with a plethora of psychological, emotional, and physical disturbances in adulthood, childhood sexual abuse appears most distinctively overrepresented in subjects with depressive (1–4), anxiety (5), personality (6–8), and eating disorders (9); in those who display self-destructiveness (10, 11); and in those with low self-esteem and high interpersonal sensitivity (12).

A history of childhood sexual abuse is not uncommonly reported by patients with depressive disorders (13, 14), but inadequate and deprivational parenting have also been identified as important antecedents to later depression (15–17). It remains unclear, therefore, whether childhood sexual abuse provides an independent risk factor (i.e., alone and beyond a general adverse background factor) for onset, severity, and other parameters of depressive disorder. We report a study designed to clarify these issues.

METHOD

Subjects and Measures

Our total study group comprised 269 inpatients or outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode lasting 24 months or fewer; 171 of the patients were women and 98 were men. All were assessed by one of our mood disorders unit consultants. Full details of the study are provided elsewhere (18). After complete description of the study to the patients, written informed consent was obtained.

Patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory (19) as well as a detailed self-report questionnaire covering sociodemographic variables, previous treatments, and psychiatric family history. Earlier parenting experiences were assessed by using the Parental Bonding Instrument (20) and the Measure of Parental Style (18).

Clinical Assessment Interviews

Patients participated in a semistructured interview with a research psychologist followed by a clinical interview with a consultant psychiatrist. The first interview focused on lifetime and current episodes of depression and anxiety disorders (formalized by use of the computerized Composite International Diagnostic Interview [21]). The interview determined a wide range of current and lifetime depressive symptoms, together with histories of drug and alcohol use.

The interviewing psychiatrist assessed clinical features, generated DSM-III-R and DSM-IV depressive diagnoses, completed the 21-item Hamilton depression rating scale (22) and the DSM-III-R Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, rated severity of depression for the current episode on a 0–3-point scale, and asked a set of structured questions about past and present suicidal or self-injurious behaviors.

Childhood Environment

The interviewing psychiatrist assessed specific characteristics of the patient’s childhood environment in the first 16 years. Using 3-point rating scales (0=no, 1=possibly/likely, 2=definitely), the psychiatrist judged whether the patient had been exposed to a number of early adverse parenting characteristics, including whether the patient had experienced sexual abuse by a parent or by another person before age 16. Patients were assigned to the childhood sexual abuse group if the interviewing psychiatrist rated their exposure to sexual abuse as likely or definite. The inclusion of patients whose exposure was rated as likely was based on literature suggesting a general underestimation bias in reports of childhood sexual abuse (1, 14).

Assessment of Disordered Personality Functioning

The interviewing psychiatrist judged whether the patient had a substantial personality disturbance preceding the first depressive episode and whether the patient had a long-standing pattern of interpersonal sensitivity resulting in substantial social or occupational impairment. At the end of the interview, the psychiatrist used a 6-point scale (0=not at all to 5=extreme) to rate the extent to which each of 15 personality vignette descriptors matched the patient’s long-term personality style. These descriptors were derived from the 10 DSM-IV personality disorders plus one DSM-IV personality disorder listed for further study (depressive personality disorder), three DSM-III-R personality disorder classes (passive-aggressive, self-defeating, and sadistic), and an anxious personality descriptor (nervy, tense, and a worrier). In addition, the psychiatrist used a 4-point scale (0=no, 1=possibly, 2=probably, 3=definitely) to rate the extent to which the patient’s personality style was disordered across eight parameters defined by Millon (23): inflexible/defective, causing significant personal discomfort, reducing opportunities, inability to function effectively and efficiently, inability to adjust to the environment, vicious or self-defeating cycles, tenuous stability under stress, and personal discomfort to others. The psychiatrist also rated the degree of functionality (1=functional, 2=probably dysfunctional, 3=definitely dysfunctional) across five domains where disordered personality style might be manifested (23): intimate relationships, family relationships, peer relationships, work, and work relationships. Total parameter and domain scores were obtained by summing the eight parameter and five domain scores, respectively.

RESULTS

Reported Incidence of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Forty-six (17%) of the 269 patients reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse before the age of 16 years; 40 (87%) of these 46 patients were women. Because of the preponderance of childhood sexual abuse among women, we elected to study only women; therefore, our study group comprised the 40 women who reported childhood sexual abuse compared with the 131 women who did not report childhood sexual abuse.

The mean ages of the women who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse were 39.1 (SD=13.5, range=19–74) and 44.1 (SD=15.0, range=18–77), respectively (t=1.9, df=169, p=0.06); the trend for a between-group difference in age led us to control for current age in all analyses. The women who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse did not differ significantly on other sociodemographic variables examined, including mean number of years of education, employment, marital status, and whether they were currently involved in an intimate relationship. Of the 40 women who experienced childhood sexual abuse, five (13%) had been abused by a parent only, 28 (70%) had been abused by someone other than a parent, and seven (18%) had been abused by both a parent and someone other than a parent.

Lifetime and Current Depression and Anxiety

Few clinical features distinguished patients with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. However, patients who reported childhood sexual abuse had made more visits to their psychiatrist in the previous 2 years (mean=26.8, SD=39.0, versus mean=15.1, SD=26.9) (F=4.10, df=1, p=0.04). In addition, more patients who reported childhood sexual abuse admitted to moderate or severe levels of hopelessness at interview (37 [93%] versus 97 [74%]) (χ2=4.90, df=1, p=0.02). The groups were comparable in percentages of self-reported helplessness, sinfulness, guilt, pessimism, worthlessness, and impaired self-image. More patients who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse than patients who were not reported significant feelings of self-annoyance or self-anger (34 [85%] versus 81 [62%]) (χ2=6.04, df=1, p=0.01), and more reported that they could lose control of their anger (19 [48%] versus 34 [26%]) (χ2=5.17, df=1, p=0.02).

There was a difference between groups in severity of depression as measured by self-report Beck depression scores: the patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had a mean score of 33.7 (SD=9.5), compared with 26.9 (SD=11.4) for those who had not (F=12.65, df=1, p=0.001). There were no significant differences on other depression measures: clinician-rated Hamilton depression scores were 23.8 and 22.0, respectively, for patients who had and had not been exposed to childhood sexual abuse. The consultants’ rating of depression severity yielded similar scores for the two groups (mean=2.25 and mean=2.22, respectively), as did current Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores (mean=47.2 and mean=50.1, respectively).

No differences in lifetime history measures were observed: patients who reported childhood sexual abuse had had their first episode of major depression at 25.4 years compared with 32.0 years for those with no childhood sexual abuse; the reported number of lifetime episodes of depression were 4.0 and 3.2, respectively; and duration of the current depressive episode was 35.2 and 30.4 weeks, respectively. The two groups of patients had similar rates of nonmelancholic depression according to the criteria of DSM-III-R (22 [55%] and 75 [57%]) and DSM-IV (23 [58%] versus 79 [60%]).

Lifetime prevalence of all anxiety disorders was similar for both groups: 50% of the patients in each group were given a diagnosis of any lifetime anxiety disorder. Social phobia was the most prevalent anxiety disorder for both of the groups: it occurred in 13 (33%) of the patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse and 33 (25%) of those who had not.

Parental Environment

Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse reported having an alcoholic father than did those who had not (17 [43%] versus 26 [20%]) (χ2=6.77, df=1, p=0.01). No other differences in psychiatric family history were evident.

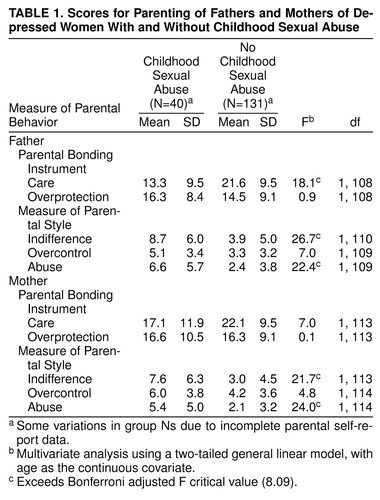

Table 1 presents the patients’ scores on the Parental Bonding Instrument and the Measure of Parental Style. Patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had significantly lower care scores for fathers only on the Parental Bonding Instrument. These patients had significantly higher indifference and abuse scores for both parents on the Measure of Parental Style. There were no differences between the groups in Parental Bonding Instrument overprotection scores and Measure of Parental Style overcontrol scores for either parent.

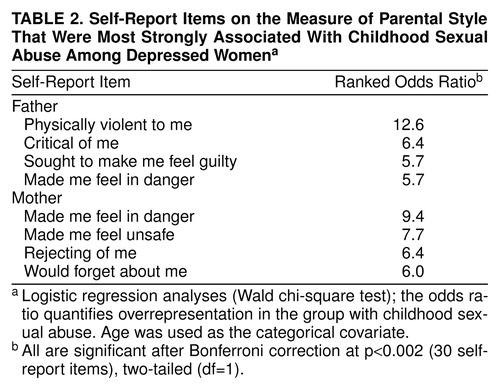

All Measure of Parental Style items were examined individually for group differences (patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse versus those who had not). Items with the four highest odds ratios (i.e., those items from the Measure of Parental Style most strongly associated with childhood sexual abuse) were ranked in descending order for fathers and mothers separately. Items of greatest distinction for fathers identified physical violence, criticism, making the child feel guilty, and making the child feel in danger. For mothers, distinctive items reflected lack of protection and maternal distance (table 2).

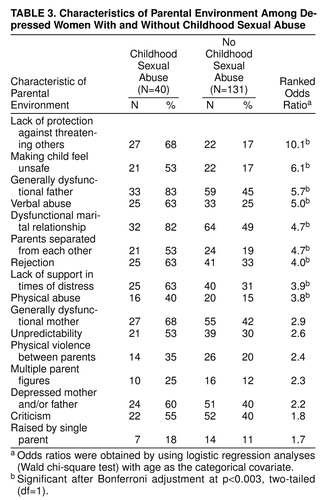

Table 3 lists the percentages of patients with and without exposure to childhood sexual abuse who reported certain parental environment characteristics during childhood. Lack of protection against threat posed by others was the most overrepresented experience affirmed by the childhood sexual abuse group. Other overrepresented characteristics were being made to feel unsafe, a dysfunctional father, verbal abuse, and exposure to an unstable relationship between parents. Hence, the general nature of the childhood environment (as measured by the Parental Bonding Instrument, the Measure of Parental Style, and interview-rated parental environment items) was able to distinguish patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse distinctly from those with no childhood sexual abuse.

Self-Injurious and Drug Use Behaviors

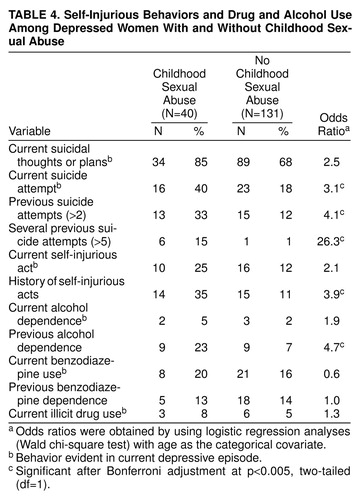

There were some notable differences in self-injurious behaviors between the two groups (table 4). Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had made a suicide attempt during their current depression, and they had also made more previous suicide attempts. Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had a previous history of self-injury or self-mutilation, and more had been dependent on alcohol in the past. However, current alcohol dependence, past and present benzodiazepine use, and illicit drug use were similar across both groups. These results may have been affected by the fact that we excluded from the study patients with drug- or alcohol-induced depression.

Personality

More patients with exposure to childhood sexual abuse than patients with no exposure (26 [65%] versus 42 [32%]) were rated as having evidence of substantial personality disturbance before their current depressive episode (χ2=12.30, df=1, p=0.001). Similarly, patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse were significantly more likely to admit to a long-standing pattern of interpersonal sensitivity (27 [68%] versus 50 [38%]) (χ2=8.80, df=1, p=0.003).

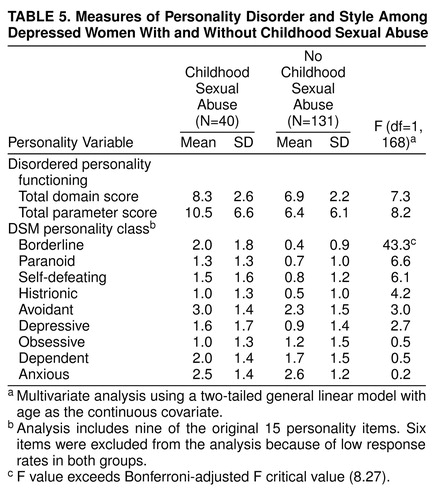

Table 5 examines the differences between the groups on a variety of measures of disordered personality function as well as styles underlying separate personality disorders. Nonsignificant trends were observed for higher domain and parameter dysfunction scores for the patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. However, the only personality item score that was significantly higher for this group was the borderline descriptor.

Multivariate Analyses

Separate logistic regression analyses were used to identify any influence of the borderline personality style variable on the association between childhood sexual abuse and suicidal and self-injurious behaviors. Borderline scores, childhood sexual abuse status, and age (less than 35, 35–50, or more than 50 years) as a categorical covariate were entered into a logistic regression model with current suicide attempt as the dependent variable. The chi-square improvement statistics were 7.20 (df=1, p=0.01) for borderline; 1.37 (df=1, p=0.24) for childhood sexual abuse, and 0.37 (df=1, p=0.83) for age. These results indicate that higher scores on the borderline item were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of there having been a suicide attempt during the current episode. Being in the childhood sexual abuse group did not add further predictive value to the chance of making a current attempt. This analysis was repeated with several suicide attempts (more than five) as the dependent variable. Again the analysis indicated that the borderline descriptor was a dominant predictor of having made more than five previous attempts at suicide (χ2=7.43, df=1, p=0.006) and that the childhood sexual abuse variable (χ2=1.04, df=1, p=0.31) and age (χ2=2.82, df=1, p=0.24) did not add any predictive value beyond that of the borderline descriptor for the existing relationship between childhood sexual abuse and previous suicide attempts.

A further analysis that used previous self-injury as the dependent variable yielded the same result. Borderline scores (χ2=26.37, df=1, p<0.001) rather than childhood sexual abuse status (χ2=0.26, df=1, p=0.69) were associated with the increased likelihood of a history of self-injury.

Thus, the borderline descriptor stood out as a significant mediating influence of self-harmful behaviors in that it appeared to account for the connection between childhood sexual abuse and self-harm. Because of its obvious significance, the borderline variable was examined against other rated parental characteristics. First, all parental environment predictors were correlated with borderline scores to assess whether any overlap existed. Modest but significant relationships were observed between borderline scores and paternal care (r=–0.34, p<0.01), maternal indifference (r=0.40, p<0.01), maternal abuse (r=0.30, p<0.01), paternal indifference (r=0.37, p<0.01), paternal care (r=–0.29, p<0.01), and childhood sexual abuse status (r=0.48, p<0.01). Although some overlap did exist, interpretations concerning the independent role or effect of each predictor variable could not be made because correlation coefficients were not high.

A linear regression analysis examined components of the parental environment (care scores on the Parental Bonding Instrument, indifference and abuse scores on the Measure of Parental Style, childhood sexual abuse status) associated with higher borderline scores. The regression model indicated that having a history of childhood sexual abuse was the only significant variable (t=4.66, df=7, 94, p<0.001) and that the other measures of parental environment were nonpredictive. This result indicates that childhood sexual abuse status contributed to higher borderline scores irrespective of other aberrant characteristics of the parental environment.

Similar analyses were conducted for current suicide attempt, previous attempts, and history of self-injury, with the aim of isolating any independent effects of childhood sexual abuse above and beyond other aberrant parental characteristics on these adult self-harm behaviors. For current suicide attempt, the only characteristic of the early environment that was a significant predictor was childhood sexual abuse status (χ2=4.12, df=1, p=0.04). For several previous suicide attempts, significant predictors were higher maternal indifference scores on the Measure of Parental Style (χ2=4.41, df=1, p=0.03) and having a history of childhood sexual abuse (χ2=4.44, df=1, p=0.03). For history of self-injury, childhood sexual abuse alone and independent of other characteristics had significant predictive value (χ2=4.39, df=1, p=0.03). Thus, for current suicide attempt and history of self-injury, childhood sexual abuse was the dominant predictive characteristic of the early environment, whereas for several previous suicide attempts, high maternal indifference scores and childhood sexual abuse were equally predictive characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Childhood sexual abuse has long been held to have a number of short-term and long-term consequences, including depression in adulthood. Having been sexually abused in childhood may increase the likelihood of depression or may influence the expression and severity of depression, either directly or indirectly, as a consequence of a more general aversive early environment. We studied a group of female patients with primary major depression, focusing on identifying nuances of the parental environment for those reporting childhood sexual abuse and then considering any role that childhood sexual abuse might bring to adult depression. Our study relied to a large degree on self-report data, a method that risks a range of retrospective biases, particularly in view of the fact that patients with a borderline personality style are recognized as tending to blame others. Thus, while we explore causal links, such noncausal possibilities must be conceded.

We found no sociodemographic differences between the patients who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse. Depressive features did not distinguish these two groups of patients, but patient-rated Beck depression scores were significantly higher for those who reported childhood sexual abuse. However, psychiatrist-rated estimates of the severity of depression did not differentiate the two groups. Nor was there any difference in the incidence of lifetime anxiety disorders. We found that patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported significantly more adverse childhood environment experiences and that multiple types of parental dysfunction were indicated. Patients who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse also differed in reporting higher self-injury and suicide attempt rates and in having more disordered personality functioning.

The latter differences, together with the fact that patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported more psychiatric visits and had higher self-report scores on hopelessness, self-disapproval, and the Beck inventory, may be consequences of childhood sexual abuse or may be explained by differences accounted for by overrepresentation of an identified personality disturbance (i.e., borderline style). Therefore, in this study group, childhood sexual abuse could not be clearly linked to greater severity of depressive symptoms per se but was significantly linked to antecedent environmental factors and long-standing patterns of dysfunctional behaviors.

It has been argued extensively that anomalous childhood environments can play a causal antecedent role in the development of depressive disorders. Even though most of our patients with exposure to childhood sexual abuse had been abused by someone other than a parent, they also reported a more detrimental parental environment than did depressed patients with no history of childhood sexual abuse. Although no more likely to have a family history of mental illness, patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse were more likely to have grown up with an alcoholic father, a finding that has been reported by others (24). Alcohol dependence, being raised by an alcoholic parent, early life stressors, and chronic psychosocial turbulence, including dissatisfaction and self-destructiveness, have also been linked to characterological depressions (25, 26).

Our patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse recalled a family environment characterized by low levels of parental care (particularly from fathers) as well as high levels of parental indifference and abuse. Similar themes, particularly that of low levels of care, have been reported in previous studies (2, 5), some of which also used the Parental Bonding Instrument (14, 27). Both of the latter studies, however, found an association between childhood sexual abuse and high levels of parental overprotection, whereas the present study found no evidence for higher Parental Bonding Instrument overprotection scores for either parent. In contrast, lack of protection against threat posed by others was the most commonly reported parental environment characteristic associated with childhood sexual abuse (table 3), which is consistent with our finding that 70% of our patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse were abused by someone other than a parent. The items in table 3 identified the childhood sexual abuse environment typically as nonprotective and nonsupportive, with conflict, violence, and marital turbulence.

Key Measure of Parental Style items for fathers portrayed a paternal relationship characterized by more general abuse and threat; for mothers, dominant items suggested a relationship characterized by lack of protection, feeling in danger, and maternal disconnectedness. Therefore, these patients, in addition to reporting sexual abuse, also recalled more severe degrees of other parental dysfunction and provided evidence of greater parental marital problems.

Our multivariate analyses allowed us to speculate on the contribution and sequential associations of aberrant parental environment, adult self-injury, and personality dysfunction for the patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. The question as to whether childhood sexual abuse may be pathogenic in any unique form or is pathogenic as part of a childhood environment with ubiquitous adversity has received attention in recent years.

For our study group, childhood sexual abuse appeared an equally predictive factor, along with high maternal indifference, of making multiple suicide attempts in adulthood, a finding highlighted in previous studies (14, 27–29). However, childhood sexual abuse was identified as a single predictor of self-destructiveness in the form of past self-injury and a current suicide attempt. In relation to personality, we found that the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and adult behaviors of self-harm (history of self-injury, several past suicide attempts, and current suicide attempt) was determined more by the influence of higher borderline descriptor scores. Thus, borderline disorder might act as a mediating factor enabling a pattern of long-standing self-destructiveness.

Figueroa et al. (30) argued that interpersonal sensitivity may act as a temperamental substrate with which sexual abuse experiences interact to effect a borderline diagnosis. For our study group, a pattern of long-standing interpersonal sensitivity was affirmed for significantly more patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse than patients with no childhood sexual abuse (68% versus 38%), a finding that provides further support for this view.

After identifying the apparently significant role of borderline personality, we aimed to track its possible evolution for our depressed group. When childhood sexual abuse was considered in conjunction with other negative aspects of the childhood environment, we found that childhood sexual abuse status was a better predictor of higher borderline personality style scores than other parental environment characteristics. Therefore, we speculate that childhood sexual abuse may well act to effect a borderline personality style as a dominant antecedent, not just as an equally negative component within a dysfunctional family style. Thus, although borderline characteristics appeared to engulf the association between childhood sexual abuse and self-harm, they could, in fact, be traced to a history of childhood sexual abuse. Even though such speculations risk circularity, we were able to disentangle some close associations for our study group, namely, that childhood sexual abuse contributed most strongly (and possibly independently) to higher borderline scores but not exclusively to some expressions of self-harm.

Even though childhood sexual abuse status had strong links to self-destructive behavior (alone or with a pattern of maternal indifference), and was a likely causative and dominant factor in the expression of borderline features, it was also closely associated with an otherwise adverse early environment. Thus, a history of childhood sexual abuse appears associated with a greater chance of exposure to earlier dysfunctional family factors, which, in turn, are associated with a greater risk of depression, disordered personality function, and other psychopathology.

Received Jan. 16, 1998; revision received June 4, 1998; accepted July 3, 1998. From the Mood Disorders Unit, Prince of Wales Hospital and the School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales; and the Department of Psychiatry, St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, N.S.W., Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Parker, Psychiatry Unit, Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick 2031, N.S.W., Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant 753205. The authors thank Kerrie Eyers, Dusan Hadzi-Pavlovic, Ian Hickie, and Christine Taylor for study assistance.

|

|

|

|

|

1. Bifulco A, Brown GW, Adler Z: Early sexual abuse and clinical depression in adult life. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:115–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Boudewyn AC, Liem JH: Childhood sexual abuse as a precursor to depression and self-destructive behavior in adulthood. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:445–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, Dechant HK, Ryden J, Derogatis LR, Bass EB: Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse—unhealed wounds. JAMA 1997; 277:1362–1368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mennen FE, Meadow D: A preliminary study of the factors related to trauma in childhood sexual abuse. J Family Violence 1994; 9:125–142Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Pribor EF, Dinwiddie SH: Psychiatric correlates of incest in childhood. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:52–56Link, Google Scholar

6. Bryer JB, Nelson BA, Miller JB, Krol PA: Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1426–1430Link, Google Scholar

7. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490–495Link, Google Scholar

8. Nigg JT, Silk KR, Westen D, Lohr NE, Gold LJ, Goodrich S, Ogata S: Object representations in the early memories of sexually abused borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:864–869Link, Google Scholar

9. Oppenheimer R, Howells K, Palmer RL, Chaloner DA: Adverse sexual experiences in childhood and clinical eating disorders: a preliminary description. J Psychiatr Res 1985; 19:357–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL: Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1665–1671Link, Google Scholar

11. Brodsky BS, Cloitre M, Dulit RA: Relationship of dissociation to self-mutilation and childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1788–1792Link, Google Scholar

12. Fox KM, Gilbert BO: The interpersonal and psychological functioning of women who experienced childhood physical abuse, incest, and parental alcoholism. Child Abuse Negl 1994; 18:849–858Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Palmer RL, Oppenheimer R, Dignon A, Chaloner DA, Howells K: Childhood sexual experience with adults reported by women with eating disorders: an extended series. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:699–703Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP: Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:721–732Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Parker G: Parental affectionless control as an antecedent to adult depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:956–960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Greenwald S, Weissman M: Low parental care as a risk factor to lifetime depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 1995; 33:173–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Parker G, Gladstone G: Parental characteristics as influences on adjustment in adulthood, in Handbook of Social Support and the Family. Edited by Pierce GB, Sarason BR, Sarason EG. New York, Plenum, 1986, pp 195–218Google Scholar

18. Parker G, Roussos J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, Austin M-P: The development of a refined measure of dysfunctional parenting and assessment of its relevance in patients with affective disorders. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1193–1203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB: A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol 1979; 52:1–10Crossref, Google Scholar

21. World Health Organisation: Composite International Interview, Version 1.2 (CIDI-A). Sydney, WHO Research and Training Centre, 1983Google Scholar

22. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Millon TA: A theoretical derivation of pathological personalities, in Contemporary Directions in Psychopathology: Toward the DSM-IV. Edited by Millon T, Klerman G. New York, Guilford Press, 1986, pp 639–669Google Scholar

24. Brown GR, Anderson B: Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood histories of sexual and physical abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:55–61Link, Google Scholar

25. Akiskal HS, Rosenthal TL, Haykal RF, Lemmi H, Rosenthal RH, Scott-Strauss A: Characterological depressions: clinical and sleep EEG findings separating “subaffective dysthymias” from “character spectrum disorders.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:777–783Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. VanValkenburg C, Akiskal HS, Puzantian V: Depression spectrum disease or character spectrum disorders? a clinical study of major depressives with familial alcoholism or sociopathy. Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:589–595Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Romans SE, Martin J, Mullen P: Women’s self-esteem—a community study of women who report and do not report childhood sexual abuse. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:696–704Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Spaccarelli S, Fuchs C: Variability in symptom expression among sexually abused girls—developing multivariate models. J Clin Child Psychol 1997; 26:24–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Stern AE, Lynch DL, Oates RK, O’Toole BI, Cooney G: Self-esteem, depression, behavior and family functioning in sexually abused girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:1077–1089Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Figueroa EF, Silk KR, Huth A, Lohr NE: History of childhood sexual abuse and general psychopathology. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:23–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar