Criminal Offending in Schizophrenia Over a 25-Year Period Marked by Deinstitutionalization and Increasing Prevalence of Comorbid Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the pattern of criminal convictions in persons with schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by both radical deinstitutionalization and increasing rates of substance abuse problems among persons with schizophrenia in the community. METHOD: The criminal records of 2,861 patients (1,689 of whom were male) who had a first admission for schizophrenia in the Australian state of Victoria in 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995 were compared for the period from 1975 to 2000 with those of an equal number of community comparison subjects matched for age, gender, and neighborhood of residence. RESULTS: Relative to the comparison subjects, the patients with schizophrenia accumulated a greater total number of criminal convictions (8,791 versus 1,119) and were significantly more likely to have been convicted of a criminal offense (21.6% versus 7.8%) and of an offense involving violence (8.2% versus 1.8%). The proportion of patients who had a conviction increased from 14.8% of the 1975 cohort to 25.0% of the 1995 cohort, but a proportionately similar increase from 5.1% to 9.6% occurred among the comparison subjects. Rates of known substance abuse problems among the schizophrenia patients increased from 8.3% in 1975 to 26.1% in 1995. Significantly higher rates of criminal conviction were found for patients with substances abuse problems than for those without substance abuse problems (68.1% versus 11.7%). CONCLUSIONS: A significant association was demonstrated between having schizophrenia and a higher rate of criminal convictions, particularly for violent offenses. However, the rate of increase in the frequency of convictions over the 25-year study period was similar among schizophrenia patients and comparison subjects, despite a change from predominantly institutional to community care and a dramatic escalation in the frequency of substance abuse problems among persons with schizophrenia. The results do not support theories that attempt to explain the mediation of offending behaviors in schizophrenia by single factors, such as substance abuse, active symptoms, or characteristics of systems of care, but suggest that offending reflects a range of factors that are operative before, during, and after periods of active illness.

The relationship between having a major mental illness and behaving in a violent or otherwise criminal manner continues to be actively debated. A consensus emerged in the 1980s and 1990s that embraced an association between mental illness and offending and in particular between schizophrenia and violent behavior (1–5). This consensus is, however, now under challenge. A view is gaining ground that the excess violence found in association with schizophrenic disorders is not a result of the illness per se but of factors such as substance abuse, the patient’s premorbid personality, and social disadvantage (6–10). It is even being argued that schizophrenia may be irrelevant to or even protective against the risk of violence (11–14).

As a result of deinstitutionalization, large numbers of people with chronic disabling mental disorders are being cared for predominantly in the community rather than in hospital settings. The adequacy of the care and support offered to mentally ill persons in the community has been questioned, and deinstitutionalization has been repeatedly linked with a supposed escalation in criminal behavior and imprisonment among persons with serious mental disorders (15–17). The rising rates of substance abuse among persons with serious mental illness have also been linked both to inadequate care and support in the community and to the supposed increase in violence in this population (18).

An earlier study based on data from only two patient cohorts (from 1975 and 1985) failed to establish the dynamics of changes in criminal behavior over the period of deinstitutionalization and particularly of the changes associated with increasing rates of comorbid substance abuse among persons with schizophrenia (19). This study examines the pattern of offending in a series of five cohorts of patients with schizophrenia admitted over the last 25 years. This study elucidates the changes that have occurred during a period when the system of care shifted from one based almost exclusively on large mental hospitals to one based entirely on care in the community and the psychiatric units of general hospitals. The longitudinal approach also gave us the opportunity to disentangle the roles of comorbid substance abuse and schizophrenia by examining the interaction between the rising levels of substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia and the pattern of criminal offending. The hypothesis that higher rates of violence among persons with schizophrenia are directly associated with the symptoms of the illness rests in part on reports that the pattern of offending among persons with schizophrenia differs from that in the general population by starting later, after the onset of active illness, and continuing longer (20). The assumption that the social dislocation and deprivation consequent on chronic disability make a major contribution to offending in persons with schizophrenia (21, 22) would also predict that offending would be concentrated after the onset of illness. To test these hypotheses, we compared the temporal pattern of offending among patients with schizophrenia to that among matched comparison subjects.

This large study of criminal behavior in persons with schizophrenia used a case-control design that allows a precise examination of the differences in patterns of offending between persons with and without this illness.

Method

The study was approved by the ethics review committees of the Victoria Department of Health, the Victoria Police Department, and Monash University.

Patient Samples

The patient cohorts were drawn from the Australian state of Victoria’s psychiatric case register, which is one of the world’s largest psychiatric registers (23). The Victorian Psychiatric Case Register covers the period from 1961 and contains data for more than 520,000 individuals. The register includes data from 95% of public outpatient, community, and inpatient services in the state but does not receive information from the private sector, which accounts for 6% of the state’s psychiatric beds (24). The register also fails to capture consultations in private psychiatric practice and consultations with general practitioners to address mental health issues. Almost all patients with schizophrenia, even those who receive most of their care in the private sector, have some contact with public services, given that all facilities for compulsory treatment and virtually all emergency and rehabilitation services are in the public sector. According to the register, 0.7% of the current population of the state of Victoria has had treatment for schizophrenia, and this proportion approaches the theoretical maximum prevalence of schizophrenia in this population.

The patient cohorts were composed of individuals who had their first contact with public mental health services in 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, or 1995 and who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia at the time of their first contact and on at least two-thirds of all subsequent contacts. Included in this broad category of schizophrenia are all diagnoses coded with DSM-IV codes 295 (ICD-10 codes F20, F25) and 297 (ICD-10 codes F22, F24). The diagnosis was made by the treating psychiatrist at the patient’s discharge or within a month of the patient’s first contact with a community service. Thus, these diagnoses represent actual clinical diagnoses, although two independent raters who used the OPCRIT system (25) to examine 100 case files had good agreement with the broad schizophrenia diagnoses made by the treating psychiatrists. The practice of determining the patient’s diagnosis at discharge or within a month of the patient’s first service contact has been shown to provide good diagnostic reliability over time (26).

Community Samples

Patterns of offending among the patient samples during the period from 1975 to 2000 were compared with those among community comparison subjects matched for age, gender, and place of residence. The comparison subjects were drawn from a database generated from criminal record searches performed as part of the state’s process for selecting citizens for jury duty. Potential jurors are randomly selected from the state’s electoral rolls, and their criminal history is checked before they are placed on jury lists. Registration for voting is compulsory in Victoria, and the electoral rolls capture 98% of the adult population. Having had a criminal conviction is not a disqualification from voting nor does it lead to removal of the person’s name from the voters’ register. Persons who are in prison for 5 years or less remain qualified to vote, although those serving sentences longer than 5 years may have their names removed from the voters’ register at 5 years and for the duration of their imprisonment. At the time the comparison subjects were selected, there were 476 people (approximately 0.0001 of the population) were serving sentences longer than 5 years (27). Deidentified copies of the criminal records of the comparison subjects matched for gender, year of birth, and area of residence with the patients with schizophrenia were made available for the present study.

Matching Procedure

To investigate patterns of offending among the patient samples, the researchers searched the database of the Victorian police department using the personal identifiers of name (surname and first name), gender, and date of birth of each member of each patient cohort. The police database records all contacts with members of the public, including all criminal charges and any subsequent convictions. Links to the national offender register allowed investigation of offenses throughout Australia. The data matching process was modeled on that used to investigate the criminal records of potential jurors, to ensure that identical procedures were followed for the patients and the comparison subjects. The researchers had no access to the names and other personal identifiers of the comparison subjects, and the police and criminal records staff had no access to the names and personal identifiers of the patients. Once record linkage was complete, the patients’ personal identifiers, other than year of birth, gender, and area of residence, were permanently removed from the database. Only data on convictions were analyzed in the present study.

Data Analysis

Convictions recorded for the patient and comparison samples were divided into 16 offense categories. The results presented here refer to convictions recorded for offenses grouped into four broad categories of violent, property-related, substance-related, and sexual offenses. We also present results for a composite category of total offending, which includes convictions recorded for any of the individual offense categories.

Violent offenses consisted of offenses that involved interpersonal violence, including assault, causing of serious injury, and homicide. This category did not include threatening behavior and property damage. Substance-related offenses included all offenses involving the possession of or trafficking in illegal drugs and all convictions for being drunk and disorderly. Sexual offenses included convictions for prostitution, but it should be noted that prostitution is legal in licensed brothels in Victoria. Thus, soliciting in the streets is the only type of prostitution likely to attract prosecution, but even that offense rarely results in conviction.

We compared the numbers of patients and matched comparison subjects who had been convicted of an offense during their lifetime to date and in the 5-year period after the patient’s first contact with the mental health service. We report data on convictions and on all judicial dispositions in which offenders were found incompetent to stand trial or were adjudicated insane. In Australian jurisdictions, findings of incompetence to stand trial or of insanity are relatively rare largely because until recently they resulted in indefinite detention in a secure psychiatric hospital. Only five subjects in the present study were found either incompetent or insane.

The true extent of substance misuse is probably underestimated by the diagnostic data recorded in the psychiatric case register because these data depend on clinicians’ adequate inquiry about and recording of the comorbidity. To allow a more accurate assessment of the interaction of substance misuse, schizophrenia, and criminal offending, we sought to increase ascertainment of substance misuse by identifying subjects with a known substance abuse problem. These subjects included those with either a diagnosis of a substance-related disorder included in the case register or a conviction for a substance-related offense.

The frequency of convictions among the patients with schizophrenia and among the comparison subjects was compared by using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Tests of significance were undertaken by using chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests, or t tests, with the level of significance set at 0.05.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The five cohorts of patients from 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995 included a total of 2,861 subjects (1,689 male patients and 1,172 female patients). The mean age at first admission was 28.1 years (SD=13.9), and the most common ages at first admission were between age 20 and 25 years. The matched comparison group included 2,861 subjects and was identical to the patient group in gender and age distribution. The number of patients in the 1995 cohort was artificially elevated by a delay in recording data for patients who were actually first seen in 1994. Separating the two groups was problematic, so all were included in the study.

Convictions

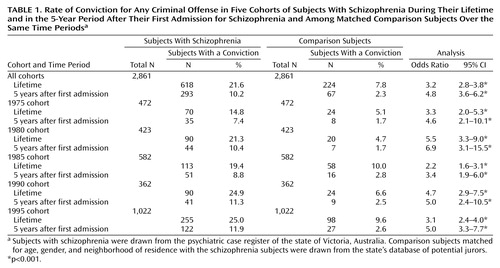

The patients with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to have been convicted of at least one offense than the community comparison subjects, both during their lifetime to date (21.6% versus 7.8%) and in the 5-year period after their first admission (10.2% versus 2.3%) (Table 1). When the cohorts were examined individually, all five were found to be more likely than the comparison subjects to have had a conviction over their lifetime and in the 5 years after their first admission (Table 1). Male patients with schizophrenia in the combined cohorts had significantly higher rates of conviction than the male comparison subjects over their lifetime (31.3% versus 11.7%) (odds ratio=3.4, 95% CI=2.9–4.1, p<0.001) and in the 5 years after their first admission (15.0% versus 3.5%) (odds ratio=4.9, 95% CI=3.7–6.6, p<0.001). The differences remained significant when the cohorts of male patients were each considered separately. For female patients, the rate of offending was significantly higher, relative to the female comparison subjects, in the combined cohorts for lifetime offending (7.7% versus 2.2%) (odds ratio=3.7, 95% CI=2.4–5.7, p<0.001) and in the 5 years after the first admission (3.3% versus 0.7%) (odds ratio=5.0, 95% CI=2.3–10.8, p<0.001), but the results for individual cohorts of female patients were not significantly different from those for the female comparison subjects.

The total number of convictions among the subjects with schizophrenia was also higher than that among the comparison subjects (8,791 versus 1,119); both male and female patients with schizophrenia had a higher total number of convictions than their matched comparison subjects (male subjects: 8,115 versus 1,045; female subjects: 676 versus 74). The mean number of convictions for each offender was significantly higher in the schizophrenia cohorts than among the comparison subjects (14.2 versus 5.0; p<0.001, t test); the male patients with schizophrenia had a higher mean number of convictions than the male comparison subjects (15.4 versus 5.3; p<0.001, t test), but there was no difference between the female patients and the female comparison subjects (mean=5.1 versus mean=2.9; n.s., t test).

The rate of criminal conviction over the lifetime to date among patients with schizophrenia gradually increased from 14.8% in the 1975 cohort to 25.0% in the 1995 cohort (Table 1). This increase occurred even though the number of years at risk for offending was greater in the earlier cohorts than in the later cohorts, because the earlier cohorts had an older average age. The patients’ rate of offending during the 5-year period after the first admission increased over the years, from 7.4% in the 1975 cohort to 11.9% in the 1995 cohort (Table 1). The rates of overall offending also increased over the years of the study in the comparison group. Among comparison subjects, the lifetime-to-date rate of offending rose from 5.1% in the group matched to the 1975 patient cohort to 9.6% in the group matched to the 1995 cohort (Table 1). Similarly, the comparison subjects showed an increase in offending in the 5 years after their matched subjects’ first admission, from 1.7% in the group matched to the 1975 cohort to 2.6% in the group matched to the 1995 cohort (Table 1). When we calculated the odds ratios for offending among subjects with schizophrenia relative to their matched comparison subjects, no consistent pattern suggestive of either a relative increase or a decrease over time in the schizophrenia group was apparent (Table 1). This finding suggests a similar increase in the rate of convictions over the period of the study among both the patients with schizophrenia and the comparison subjects.

Violent offenses

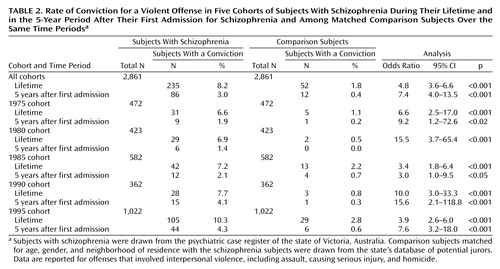

The overall frequency of violent offenses was significantly higher among the patients with schizophrenia than among the comparison subjects (8.2% versus 1.8%) (Table 2). The rate of violent offending among the patients with schizophrenia gradually increased over the years of the study from a lifetime conviction rate of 6.6% in 1975 to 10.3% in 1995 (Table 2). This increase coincided with a proportionately similar increase in the conviction rate in the comparison group, from 1.1% to 2.8%. There was no difference in the rate of increase in violent offending between the schizophrenia patients and the comparison subjects over the period of the study. The 235 patients with schizophrenia who had convictions for violent offenses over their lifetime to date had 855 separate convictions for such offenses (a mean of 3.6 per offender), compared to a total of 76 convictions accumulated by the 52 comparison subjects with convictions for violent offenses (a mean of 1.5 per offender). Thus, the rate of conviction for a violent offense was 2.4 times greater among the violent offenders with schizophrenia than among the comparison subjects who were violent offenders.

Nine subjects in the schizophrenia cohort were charged with murder. Four were convicted, one was adjudicated insane, three were convicted of lesser offenses, and one was acquitted. No murder convictions were recorded among the comparison subjects, although one comparison subject was charged and acquitted.

Male subjects in the schizophrenia cohorts had significantly more lifetime-to-date convictions for violent offenses than the male comparison subjects (13.0% versus 2.9%) (odds ratio=5.0, 95% CI=3.6–6.9, p<0.001) and significantly more convictions for violent offenses in the 5-year period after their first admission (4.6% versus 0.7%) (odds ratio=7.3, 95% CI=3.9–13.8, p<0.001). Violent offenses were largely limited to male subjects, although the rate of violent offenses by female patients with schizophrenia in the overall sample was significantly higher than that in the overall sample of female comparison subjects (1.4% versus 0.3%) (odds ratio=5.4, 95% CI=1.6–18.6, p<0.003). However, there were too few convictions for violence among women to analyze the data separately by cohort.

Property-related offenses

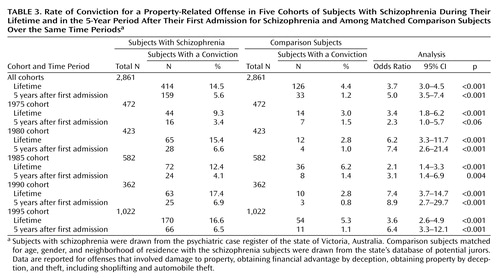

Property-related offenses were recorded for 14.5% of the patients with schizophrenia and 4.4% of the comparison subjects (Table 3). Relative to the male comparison subjects, the male schizophrenia patients had significantly higher rates of property-related offenses during their lifetime to date (20.7% versus 6.2%) (odds ratio=4.0, 95% CI=3.2–5.0, p<0.001) and during the 5 years after their first admission (7.9% versus 1.6%) (odds ratio=5.3, 95% CI=3.5–8.0, p<0.001). The differences remained significant for each of the male cohorts. In the overall sample, female patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher lifetime-to-date rate of property-related offenses than the female comparison subjects (5.6% versus 1.9%) (odds ratio=3.1, 95% CI=1.9–5.0, p<0.001) and a significantly higher rate for the 5 years after their first admission than the female comparison subjects (2.2% versus 0.5%) (odds ratio=4.4, 95% CI=1.8–10.8, p<0.001). However, the conviction rates were too low among women to allow a meaningful analysis by cohort. The rate of convictions for property-related offenses increased steadily from 1975 to 1995 among the schizophrenia patients, but the rate of increase was similar to that observed among the matched comparison subjects.

Substance-related offenses

A total of 9.4% of the schizophrenia patients and 2.3% of comparison subjects had lifetime-to-date convictions for substance-related offenses (Table 4). Male schizophrenia patients were significantly more likely to have such convictions than male comparison subjects in the total sample and in every cohort. The rates of substance-related offenses among female subjects were again too low for cohort-by-cohort analysis, although in the total sample, the female schizophrenia patients had a significantly higher rate of substance-related offenses than the female comparison subjects (1.9% versus 0.3%) (odds ratio=7.5, 95% CI=2.2–25.0, p<0.001). The frequency with which subjects with schizophrenia were convicted of a substance-related offense in their lifetime to date climbed steadily from 4.9% in 1975 to 12.9% in 1995, but this increase was matched by a proportionately similar rise among the comparison subjects (0.2% to 3.3%), resulting in no difference in the rate of increase between the schizophrenia patients and the comparison subjects (Table 4).

Sexual offenses

Male schizophrenia patients were more likely than male comparison subjects to be convicted of a sexual offense during their lifetime (1.8% versus 0.7%) (odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=1.3–5.1, p<0.01). However, the rates of sexual offending were too low to allow a meaningful analysis by cohort for male subjects. Only nine convictions for sexual offenses occurred among female subjects overall, which precluded meaningful analysis.

Time of First Treatment and Age Relative to Time of Offending

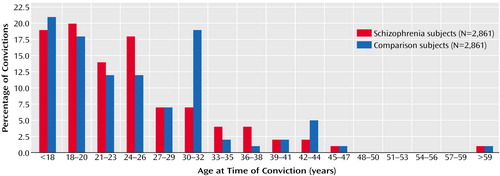

Among the patients with schizophrenia who had a criminal record, the first conviction for any offense occurred before the first psychiatric contact in 72.7% of subjects. The mean ages at first conviction did not differ significantly between the schizophrenia patients (mean=24.8 years, SD=11.2) and the comparison subjects (mean=25.6 years, SD=10.8). There was no difference between the groups in the age distribution at the time of conviction (Figure 1). Among the patients with schizophrenia who had been convicted for a violent offense, 63.8% had their first conviction for violence before their first contact with mental health services. Relative to the comparison subjects, the patients with schizophrenia did not have their first offense at a later age nor did they continue their criminal careers to a greater age.

Interaction of Substance Misuse, Schizophrenia, and Offending

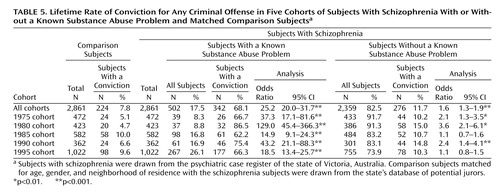

In the overall sample of schizophrenia patients, 327 (11.4%) had a record of a comorbid diagnosis of a substance use disorder and 94 of those subjects also had a conviction for a substance-related offense. Among the 269 schizophrenia patients (9.4%) who had a conviction for a substance-related offense, 175 (6.9%) subjects did not have a recorded comorbid diagnosis of a substance use disorder. Thus a total of 502 (17.5%) patients with schizophrenia had a known substance abuse problem; 421 of those subjects were male, and 81 were female. The schizophrenia patients who also had a known substance abuse problem were significantly more likely to have been convicted of an offense during their lifetime to date than those without a known substance abuse problem (68.1% versus 11.7%) (odds ratio=16.1, 95% CI=12.9–20.2, p<0.001). The relationship between a higher rate of total offending and known substance abuse problems held for both male schizophrenia patients (73.4% versus 17.3%) (odds ratio=13.2, 95% CI=10.2–17.2, p<0.001) and female schizophrenia patients (40.7% versus 5.2%) (odds ratio=12.5, 95% CI=7.4–20.9, p<0.001).

The rate of known substance abuse problems among patients with schizophrenia increased steadily from 8.3% in the 1975 cohort to 26.1% in the 1995 cohort (Table 5). This increase paralleled the rise in the rate of a recorded diagnosis of a comorbid substance-related disorder among subjects with schizophrenia from 3.8% in 1975 to 19.0% in 1995. However, the proportion of subjects with criminal offenses remained relatively stable over time among both the schizophrenia patients with a known substance abuse problem (approximately 60%–80%) and those without a known substance abuse problem (10%–15%), except for the higher rate of nearly 87% among the subjects with a known substance abuse problem in the 1980 cohort.

The results for violent offending show a similar overall pattern, with a significantly higher rate in the patients with a known substance abuse problem, compared to those without a known substance abuse problem (26.1% versus 4.4%) (odds ratio=7.7, 95% CI=5.8–10.01, p<0.001), and a similar pattern in the various cohorts. Among male schizophrenia patients, 125 (29.7%) subjects with a known substance abuse problem had a conviction for violence during their lifetime to date, compared to 94 (7.4%) subjects without a known substance abuse problem. Relative to the rate of violent offenses in the male comparison subjects (2.9%), the rate of violent offenses was significantly higher both among male schizophrenia patients with a known substance abuse problem (odds ratio=14.1, 95% CI=9.9–20.1, p<0.001) and male schizophrenia patients without a known substance abuse problem (odds ratio=2.7, 95% CI=1.9–3.8, p<0.001). The proportions of patients in these two groups who had a violent offense remained relatively constant over the years, ranging from 4% to 5% for those without a known substance abuse problem and 20% to 30% for those with a known substance abuse problem.

Among the schizophrenia patients who did not have a known substance abuse problem, lifetime rates of offending remained significantly higher than those among the comparison subjects for total offending (11.7% versus 7.8%) (odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=1.3–1.9, p<0.001), violent offenses (4.4% versus 1.8%) (odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.8–3.5, p<0.001), and property-related offenses (7.6% versus 4.4%) (odds ratio=1.8, 95% CI=1.4–2.3, p<0.001). The rate of total offending among the schizophrenia patients with a known substance abuse problem differed markedly from the rate for the matched comparison subjects (Table 5). A marked difference between these groups was also found for violent offending (26.1% versus 18%) (odds ratio=19.1, 95% CI=13.6–26.8, p<0.001). Relative to the rates of total offending among the comparison subjects, the rates in the schizophrenia patients without a known substance abuse problem were significantly greater in the 1975, 1980, and 1990 cohorts but not in the 1985 and 1995 cohorts (Table 5). The difference in the rates of violent offending between the schizophrenia subjects without a known substance abuse problem and the matched comparison subjects was significant in 1975 (5.3% versus 1.1%) (odds ratio=5.2, 95% CI=2.0–13.9, p<0.001) but nonsignificant in 1995 (4.4% versus 2.8%) (odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=0.9–2.6, n.s.).

Discussion

Main Findings

A clear association emerged between having schizophrenia and higher rates of conviction for a wide range of criminal offenses, including violent offenses. The frequency with which those entering the mental health system with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were convicted of offenses gradually increased over the period of deinstitutionalization between 1975 and 1995 but was matched by a proportionately similar increase among community comparison subjects. Subjects with both schizophrenia and substance abuse problems contributed disproportionately to the conviction rates, although the dramatic escalation in the number of subjects with schizophrenia who were known to have a substance abuse problem over the 25-year study period was not marked by an increase in offending, relative to the rates in the general population. No clear associations emerged between the onset of active illness in schizophrenia and the pattern of offending.

Limitations of the Study

The study examined data for subjects who had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia and had been treated for schizophrenia in a public mental health service. The diagnoses were not based on research diagnostic criteria but were made clinically by treating psychiatrists, virtually all of whom were trained in the use of the DSM system. The criteria used to define the study population excluded persons with drug-induced and brief psychotic episodes but included those with schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder.

The applicability to other countries of a study based on Australian data may quite reasonably be questioned. Direct comparison of crime rates across national boundaries is problematic, but the available data based on reported offense rates per 100,000 population suggest, for example, that over the period of the study the frequency of violent crimes in Victoria was only about one-third lower than in the United States (452 per 100,000 population versus 731 per 100,000 population). The differences in homicide rates were more marked (1.2 per 100,000 population versus 9.4 per 100,000 population), which could reflect the greater availability of guns in the United States combined with a higher rate of nondomestic killings (28, 29). In the case-control study reported here, however, the differences in rates of offending between the schizophrenia patients and the matched comparison subjects should be independent of the base rate of offending. It has been suggested that homicides by mentally ill offenders occur at similar rates across countries, cultures, and time periods (about 0.16 per 100,000 population per year) (30). If that hypothesis is correct, the proportion of homicides committed by persons with schizophrenia would be lower in societies with a higher overall homicide rate and higher in societies with a low homicide rate. However, more recent studies of homicide by persons with schizophrenia that have been based on clinical data, rather than court adjudications, have indicated rates of between 5% and 10%, irrespective of the local overall homicide rate (1, 31–34). Extrapolation of these findings to other forms of offending would suggest that although absolute levels of particular forms of offending may vary between Australia and other countries, including the United States, the rate of offending by persons with schizophrenia, relative to the general population, would be similar. Extrapolation must also take into consideration different patterns of mental health service provision, which, for example in the United States, vary widely between local jurisdictions, some of which have community services that are less extensive and less well funded than those in Victoria.

In selecting the matched comparison subjects in this study, it was not possible to exclude the 0.7% of individuals with schizophrenia in the community who might also have been included in the Victorian Psychiatric Case Register. This possibility introduces a bias against finding a difference between the schizophrenia group and the comparison group in our study. In addition, data were not available to determine whether any cohort members with schizophrenia had died or left the country. In contrast, the comparison group consisted of individuals known to be alive and living in Victoria at the time of data matching. This difference could introduce another bias against detecting a true higher rate of offending among the schizophrenia cohorts.

Convictions were used to quantify criminal behaviors, but this method underestimates the true prevalence of criminal behaviors. The focus on convictions captures preferentially more severe and visible instances of offending. Far higher frequencies of violent behavior are ascertained in studies that augment such official records with self-reports. Monahan and colleagues (6), for example, reported rates of assaultive behavior in schizophrenia that were several times greater than the rates for violent offenses in the current study. The current study documented serious violent and criminal behaviors over a long period of time and could be seen as representing primarily the length and depth, rather than the breadth, of the relationship between schizophrenia and violent and other offending behaviors.

The progression from offending to conviction is influenced by a range of chance and procedural variables that may affect persons with mental disorders differently than they affect mentally competent persons. For example, persons with mental disorders may be more likely to be apprehended when they offend, although the evidence remains contradictory (35–37). Once the decision to charge an individual has been made, a number of diversionary mechanisms may come into effect to move mentally ill offenders out of the criminal justice system and into the mental health system. In the current study, 757 patients with schizophrenia had been charged with at least one offense during their lifetime. Of those subjects, 613 (81.0%) were ultimately convicted and five (0.7%) were adjudicated insane or incompetent. A higher proportion of comparison subjects charged with offenses were ultimately convicted (92.2%). If the patients with schizophrenia and the comparison subjects were equally likely to have committed the offense with which they were charged, our figures would underestimate the true differences in the frequency of offending behaviors between the schizophrenia group and the comparison group.

Schizophrenia and Criminal Convictions

Despite having systematic biases likely to reduce the probability of detecting the true frequency of convictions among the subjects with schizophrenia, this study provides evidence of an association between schizophrenia and higher rates of conviction for all major types of offending, including violent offenses. The total number of convictions among subjects who had any offenses was higher for the schizophrenia patients than for the comparison subjects. In short, both the chances of offending and the chances of recidivism were significantly higher among the patients with schizophrenia than among the comparison subjects. An earlier study in this community examined the relationship between schizophrenia and offending by tracing the psychiatric histories of the subjects with schizophrenia who were convicted of offenses, albeit only for the years 1993–1995 (33). The odds ratios for having a history of schizophrenia among subjects convicted of any offense (odds ratio=3.2) or of a violent offense (odds ratio=4.4) closely paralleled the results for the schizophrenia patients in this study (any conviction: odds ratio=3.2; conviction for a violent offense: odds ratio=4.8). Thus, whether the study examines offending in schizophrenia or schizophrenia among offenders, in the community studied and during the period studied, the result is much the same: a significantly and substantially higher rate of offending is associated with schizophrenia.

Convictions for violent offenses

Earlier research has suggested that the majority of convictions for violent offenses among persons with schizophrenia are for trivial offenses such as threatening behavior and property damage (38). In the current study, however, the violent offenses committed by the patients with schizophrenia were predominantly serious offenses. Most convictions for violent offenses were for robbery with violence and inflicting actual or grievous bodily harm. Four subjects with schizophrenia were convicted of murder, and one subject charged with murder was adjudicated insane. The frequency of murder convictions among the subjects with schizophrenia was far higher than would have been expected by chance in a community whose annual murder rate during the study period fluctuated between 1 and 1.4 per 100,000 population (29).

In this study, 8.2% of all subjects with schizophrenia, and 13.0% of male subjects with schizophrenia, were convicted of a violent offense. Relative to the comparison group, subjects with schizophrenia were between 3.6 and 6.6 times more likely to have at least one conviction for a violent offense and subjects with such convictions committed 2.4 times as many offenses. These findings suggest that as much as 6%–11% of violent offending in the community could be attributable to persons with schizophrenia (calculated as the proportion of the population with schizophrenia multiplied by the relative likelihood of having a conviction for a violent offense multiplied by the number of actual offenses for each violent offender: 0.7% × (3.6 or 6.6) × 2.4=6.0%–11.1%). Among male schizophrenia patients who had a known substance abuse problem, nearly 30% had a conviction for a violent offense. These rates of offending are not only of clinical relevance but potentially of social relevance.

Convictions for property-related offenses

Convictions for property-related offenses were the most commonly recorded type of conviction among the subjects with schizophrenia. The social and occupational dysfunction associated with schizophrenia, which can drive patients into the ranks of the poor and the isolated, may contribute to property-related offending. The vast majority of the convictions for property-related offenses were for minor thefts or theft of items from shops. Such crimes are predominantly opportunistic, are seemingly aimed at the acquisition of inexpensive goods or small sums of money, and are far removed from the crimes of career criminals. The failure to provide adequate social and financial support to persons who are disabled by schizophrenia may be contributing to the use of prisons as primary providers of mental health care and to the use of judicial sentences as a primary form of intervention.

Schizophrenia as a risk factor for offending

When the rate of offending in persons with schizophrenia is compared to that in persons with other forms of mental disorder, particularly severe personality disorders, schizophrenia may appear to actually be protective against violent offending and other types of offending (11, 12). However, when a large cohort of persons with schizophrenia is compared to a general population group, as in the current study, there is a clear association between schizophrenia and higher rates of offending, including violent offending. Having schizophrenia is therefore a risk factor for offending and in particular for violent offending. Associations such as these do not necessarily reflect causal connections, but they do raise the question of the nature of the relationship between having schizophrenia and being more likely to be convicted of criminal offenses.

Deinstitutionalization and Offending

The process of deinstitutionalization began later in Victoria than in most of the United States, but there has been a similar decrease in bed numbers in both locations (15). In 1975, treatment services in Victoria were still dominated by large psychiatric hospitals, which had about 5,000 beds (18 per 10,000 population). Bed numbers decreased steadily until 1985, when the first of the large asylums was closed and the initial group of 19 community-based services opened (39). The last of the asylums was closed in 1993. In the 1990s, treatment was provided primarily in community services, and psychiatric beds were limited to about 500 acute-care and 120 extended-care beds (1.8 per 10,000) situated in general hospitals. Currently, the only stand-alone inpatient psychiatric facility in the state is a 100-bed forensic psychiatric hospital.

There has been considerable concern that deinstitutionalization has resulted in an increase in the number of people with serious mental disorders who commit criminal offenses and are sent to jail or prison. Lamb and Bachrach (15) acknowledged that “this premise is difficult to prove scientifically, because of a lack of good studies of the number of mentally ill persons who were incarcerated before deinstitutionalization” (p. 1042). They could have added that there is a similar lack of data on the rate of offending among mentally ill persons before the era of deinstitutionalization.

The results of the current study indicate an increase in the absolute levels of offending among persons with schizophrenia over the last 25 years. Clinicians are likely to be well aware that their patients’ rate of involvement with the criminal justice system has increased without necessarily also being aware of the increased rate of criminal convictions in the general population. The base rate for convictions among persons with schizophrenia in the 1975 cohort was already more than 14%, and the increase to 25% in the 1995 cohort, although proportionally similar to the increase in the general population, could quite reasonably have been experienced by clinicians and the general public as being of a different order. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is a widespread belief that the increased rate of offending among persons with schizophrenia over the period of deinstitutionalization is linked to the change from institutional to community care. This study demonstrates that this impression, however understandable, is false.

Rates of imprisonment have greatly increased in both the United States and Australia over the last 25 years. In Victoria the prison population grew from 1,651 in 1975 to 3,062 in 2000, although the rate of imprisonment continues to be lower in Victoria than in most U.S. states (27). It would be surprising if persons with schizophrenia who offend were not also being caught up in this enthusiasm for incarceration. Large numbers of persons with serious mental disorders are now being housed in jails and prisons, but this study suggests that this phenomenon reflects primarily policies within the criminal justice system rather than the effects of deinstitutionalization (10).

Substance Abuse, Schizophrenia, and Criminal Convictions

Substance abuse has been suggested as the critical mediator of the association between schizophrenia and offending, particularly violent offending. In this study the rates of known substance misuse among subjects with schizophrenia steadily increased from 8.3% in 1975 to 26.1% in 1995, and had we examined a 2000 cohort, the rate would have been well over 30%. Subjects with schizophrenia were far more likely to offend if they also had a substance abuse problem. As the rate of substance abuse increased over time, a greater proportion of the total amount of convictions in each succeeding cohort was accounted for by patients with both schizophrenia and substance abuse. Patients with substance abuse problems accounted for 37% of all lifetime-to-date offending in the 1975 cohort and 69% in the 1995 cohort. As a result, by 1995, the rate of overall offending, and of violent offending in particular, among schizophrenia patients without a known substance abuse problem had ceased to be significantly greater than that among the comparison subjects. Had the study been confined to subjects recruited after 1990, it is likely that the conclusion reached would have been that patients with schizophrenia but no substance abuse problem were no more likely to offend than the general population. Such findings are occasionally interpreted to mean that it is the substance abuse—not the schizophrenia—that is associated with higher rates of offending. Such a separation would be justified only if they were truly independent variables. Having schizophrenia, however, is associated with increased rates of substance abuse (40).

Over the 25 years of the study period the rate of substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia escalated, but the rate of criminal convictions, although it increased, increased at much the same rate as in the general population. This study indicates that schizophrenia has an association with higher rates of criminal offending that is independent of substance abuse and also suggests that to some extent patients with a predisposition to offending are also more prone to abuse substances. This finding in no way reduces the importance of the presence of substance abuse in schizophrenia as a marker of an increased risk of future offending. Nor is it incompatible with the assumption that the presence of substance abuse increases the risk of offending among persons with schizophrenia to an even greater extent. It simply indicates that substance abuse is only part of the story.

Convictions and the Onset of Schizophrenia

Some researchers have been argued that the higher rates of offending in general and of violence in particular among persons with schizophrenia are related directly to the symptoms of the schizophrenic illness (41–43). Others have, however, failed to find clear associations between active symptoms and violent behavior (44). One alternative to explaining the higher rate of offending by the influences of active symptoms is that persons with preexisting predispositions to violent and criminal behavior become even more prone to offending when they develop schizophrenia. A final hypothesis would be that crime and schizophrenia arise from common roots, be those roots genetic, social, or developmental.

If the active symptoms were the most important contributor to offending, then any increase in convictions should postdate the onset of active illness, with the result that offending would start later and persist longer than in offenders without mental illness. One objection to this hypothesis is that active symptoms are likely to have been present for some years before the first admission. Even so, if active symptoms were a major driver of offending, their presence should still have altered the overall temporal pattern of offending, which was not found. The findings are compatible, however, with there being two broad groups of offenders among patients with schizophrenia: the first and by far the largest being made up of those with a pattern of antisocial behavior dating back to childhood and adolescence and the second consisting of those who begin offending in their 30s and 40s, among whom homicide offenders are most likely to be found (45). Previous findings of a later age at onset of offending in schizophrenia have often depended heavily on studies of homicide offenders (20), which may explain why we failed to confirm the earlier suggestions of later onset. Our results do not exclude the influence of active symptoms on individual acts of offending, but they give no support to the argument that the bulk of the criminality associated with schizophrenia reflects simply the presence of such symptoms.

Schizophrenia is more than the sum of the associated positive disturbances of mental state, such as delusions and hallucinations. An episode of active psychosis can involve a subsequent erosion of the personality and the emergence of cognitive deficits that disable the individual even when such symptoms are in abeyance. At least some patients with schizophrenia may have a neurodegenerative disorder associated with defects of frontal lobe function that are present before the emergence of active symptoms (46). Deteriorating interpersonal and social relationships often predate the onset of overt disturbances of mental state in schizophrenia. In short, the factors that influence the presence of criminal behavior in schizophrenia are unlikely to be confined to the effects of active illness but appear to reflect a complex interaction between the deficits in social, psychological, and brain function that precede, accompany, and follow the overt disturbances of mental state. These influences are often compounded by the social context in which many persons with schizophrenia live.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a significant association between having schizophrenia and having a higher frequency of criminal convictions, compared with the general population. This association was found despite a number of systematic biases in the study methods that militated against detecting a higher rate of convictions among the subjects with schizophrenia. The rate of criminal offending among the subjects with schizophrenia is of both clinical and social significance and cannot be dismissed as having only trivial relevance to the amount of crime in the community.

Associations may point to the possibility of causal links, but they are not themselves expressions of causality. This study places in question some of the simpler single-factor hypotheses about the mediation of violent and criminal behaviors in schizophrenia. The study gives no support to the idea that deinstitutionalization and community care have led to higher rates of criminal and violent behavior among persons with schizophrenia. The strong relationship between comorbid substance abuse and offending in schizophrenia is confirmed, but the data on convictions over a 25-year period during which comorbid substance abuse escalated dramatically cast doubt on the role of substance abuse alone in accounting for the higher rates of offending. Theories that attribute the excess of violent and criminal behaviors in schizophrenia to the baleful influence of active symptoms predict that the criminal careers of persons with schizophrenia will differ by starting later and being concentrated in the period after the emergence of active illness. These theories were not supported by this study.

The association between schizophrenia and a higher rate of criminal convictions is likely to reflect the concatenation of a range of deleterious influences. If mental health services are to further the interests of both their patients and the community, they must become involved in identifying and treating the social and psychological factors that not only disable the patients they treat but also predispose those patients to continued offending. The findings of the current study challenge clinicians and policy makers to recognize that persons with schizophrenia have high rates of problem behaviors that require improved assessment and treatment and also to ensure that such results are not used to further stigmatize a sick and disadvantaged minority.

|

|

|

|

|

Received May 21, 2003; revision received Aug. 19, 2003; accepted Sept. 28, 2003. From the Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health and the Department of Psychological Medicine, Monash University, Victoria, Australia; and the Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria, Parkville, Victoria, Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mullen, Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health, Locked Bag 10, Fairfield, Victoria 3078, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Victorian Department of Human Services and the Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health. The study was facilitated by Project Beacon, an initiative of the Victoria Police Department to increase knowledge and skills of police in dealing with persons with mental disorders.

Figure 1. Relation of Age to Convictions for Any Criminal Offense Among Subjects With Schizophrenia and Matched Comparison Subjectsa,b

aSubjects with schizophrenia were drawn from the psychiatric case register of the state of Victoria, Australia. Comparison subjects matched for age, gender, and neighborhood of residence with the schizophrenia subjects were drawn from the state’s database of potential jurors.

bUp to the time of subject matching in 2001, subjects with schizophrenia had a total of 8,791 convictions and comparison subjects had a total of 1,119 convictions. Subjects age 48–60 years had convictions at rates of less than 0.5%, which are not represented in the figure. No consistent differences emerge between groups, although the comparison subjects in the 30–32-year age group had significantly more convictions than subjects with schizophrenia in that age group.

1. Taylor PJ, Gunn J: Violence and psychosis, I: risk of violence among psychotic men. Br Med J 1984; 288:1945–1949Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Taylor PJ, Gunn J: Violence and psychosis, II: effect of psychiatric diagnosis on conviction and sentencing of offenders. Br Med J 1984; 289:9–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, Jono RT: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:761–770Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Hodgins S: Mental disorder, intellectual deficiency, and crime—evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:476–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Monahan J: Mental disorder and violent behavior. Am Psychol 1992; 47:511–521Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, Appelbaum PS, Clark Robbins P, Mulvey EP, Roth LH, Grisso T, Banks S: Rethinking Risk Assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

7. Moran P, Walsh E, Tyrer P, Burns T, Creed F, Fahy T: Impact of comorbid personality disorder on violence in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:129–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Arseneault L, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Taylor P, Silva P: Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: results from the Dunedin Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:979–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nestor PG: Mental disorder and violence: personality dimensions and clinical features. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1973–1978Link, Google Scholar

10. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, Hadley TR: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:565–573Link, Google Scholar

11. Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, Cormier CA: Violent Offenders: Appraising and Managing Risk. Washington DC, American Psychological Association, 1998Google Scholar

12. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Roth LH, Silver E: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:393–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K: The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta analysis. Psychol Bull 1998; 2:123–142Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, Long JD: Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:1358–1366Link, Google Scholar

15. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL: Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:1039–1045Link, Google Scholar

16. Torrey EF: Out of the Shadows: Confronting America’s Mental Illness Crisis. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1997Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck RA, Banks S, Pandiani J, Hoff R: Bed closures and incarceration rates among users of Veterans Affairs mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:1282–1287Link, Google Scholar

18. Swartz JA, Lurigio AJ: Psychiatric illness and comorbidity among adult male jail detainees in drug treatment. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:1628–1630Link, Google Scholar

19. Mullen PE, Burgess P, Wallace C, Palmer S, Ruschena D: Community care and criminal offending in schizophrenia. Lancet 2000; 355:614–617Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wessely SC, Castle D, Taylor PJ: The criminal careers of incident cases of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1994; 24:483–502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Steadman HJ, Silver E: Immediate precursors of violence among persons with a mental illness: a return to a situational perspective, in Violence Among the Mentally Ill—Effective Treatments and Management Strategies. Edited by Hodgins S. Montreal, Kluwer Academic, 2000, pp 35–48Google Scholar

22. Silver E: Mental disorder and violent victimization: the mediating role of involvement in conflicted social relationships. Criminology 2002; 40:191–212Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Eaton WW, Mortensen PB, Herrman H, Freeman H, Bilker W, Burgess P, Wooff K: Long-term course of hospitalization for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:217–228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Burgess PM, Joyce CM, Pattison PE, Finch SJ: Social indicators and the predication of psychiatric inpatient service utilization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1992; 27:83–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness: development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:764–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Krupinski J, Alexander L, Carson N: Patterns of Psychiatric Care in Victoria: Health Commission of Victoria Special Publication 12. Melbourne, Victorian Government Printer, 1982Google Scholar

27. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Prisoners in Australia. Canberra, Australia, Federal Government Printer, 2001Google Scholar

28. Reiss AJ, Roth JA: Understanding and Preventing Violence. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1993Google Scholar

29. Recorded Crime, Australia, 1999: Catalog Number 4510.0. Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2000Google Scholar

30. Coid J: The epidemiology of abnormal homicide and murder followed by suicide. Psychol Med 1983; 13:855–860Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Wilcox DE: The relationship of mental illness to homicide. Am J Forensic Psychiatry 1985; 6:3–15Google Scholar

32. Eronen M, Tiihonen J, Hakola P: Schizophrenia and homicidal behavior. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:83–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P, Palmer S, Ruschena D, Browne C: Serious criminal offending in mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:477–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Erb M, Hodgins S, Freese R, Müller-Isberner R, Jöckel D: Homicide and schizophrenia: maybe treatment does have a preventive effect. Crim Behav Ment Health 2001; 11:6–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Robertson G: Arrest patterns among mentally disordered offenders. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:313–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Teplin LA: Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rates of the mentally ill. Am Psychol 1984; 39:794–803Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Engel RS, Silver E: Policing mentally disordered suspects: a reexamination of the criminalization hypothesis. Criminology 2001; 39:225–252Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Lindqvist P, Allebeck P: Schizophrenia and crime: a longitudinal follow-up of 644 schizophrenics in Stockholm. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:345–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Health and Community Services: Victoria’s Mental Health Service: The Framework for Service Delivery. Melbourne, Victorian Government Publications, 1996Google Scholar

40. Rachbeisel J, Scott, J, Dixon L: Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of research. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:1427–1434Link, Google Scholar

41. Taylor PJ: Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 147:491–498Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Link BG, Stueve A, Phelan J: Psychotic symptoms and violent behaviours: probing the components of “threat/control-override” symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:555–560Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Junginger J: Psychosis and violence: the case for a content analysis of psychotic experience. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:91–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J: Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:566–572Link, Google Scholar

45. Hodgins S, Côté G, Toupin J: Major mental disorders and crime, in Psychopathy: Theory Research and Implications for Society. Edited by Cook D, Forth A, Hare RD. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer, 1998, pp 231–256Google Scholar

46. Weinberger DR: Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:660–669Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar