Bed Closures and Incarceration Rates Among Users of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined incarceration rates of users of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mental health services in 16 northeastern New York State counties between 1994 and 1997—a time of extensive bed closures in the VA system—to determine whether incarceration rates changed during this period. METHODS: Data were obtained for male patients who used inpatient and outpatient VA mental health services between 1994 and 1997 and for men incarcerated in local jails during this period. For comparison, services use and incarceration data were obtained for all men who received inpatient behavioral health care at community general hospitals and state mental hospitals between 1994 and 1996 in the same counties. Probabilistic population estimation, a novel statistical technique, was employed to evaluate the degree of overlap between clinical and incarceration populations without relying on person-specific identifiers. RESULTS: Of all male users of VA mental health services between 1994 and 1997, a total of 15.7 percent—39.6 percent of those age 18 to 39 years and 9.1 percent of those age 40 years and older—were incarcerated at some time during that period. Dual diagnosis patients had the highest rate of incarceration (25 percent), followed by patients with substance abuse problems only (21 percent) and those with mental health problems only (11 percent). The rate of incarceration among male patients hospitalized in VA facilities was lower than among men in general hospitals or state hospitals (11.6 percent, 23 percent, and 21.7 percent, respectively), but was not significantly different. No significant increase occurred in the annual rate of incarceration among VA patients from 1994 to 1977 (3.7 percent to 4 percent), despite extensive VA bed closures during these years. CONCLUSIONS: Substantial proportions of mental health system users were incarcerated during the study period, especially younger men and those with both substance use and mental health disorders. Rates of incarceration were similar across health care systems. The closure of a substantial number of VA mental health inpatient beds did not seem to affect the rate of incarceration among VA service users.

Various studies have demonstrated that mental illness is far more prevalent among jail detainees than among the general population (1,2,3), and that the number of jail detainees with mental illness has increased substantially in recent years (4). These findings have raised concern that some people with mental disorders are inappropriately channeled into the criminal justice system because of budget-driven reductions in the number of public mental hospital beds and an inadequate supply of community-based mental health services (5,6). In response to this concern, jail diversion programs have been established in a growing number of localities to identify arrestees with mental illness and divert them into public mental health systems, where they can receive more appropriate and effective care (7,8,9).

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between mental illness and criminal behavior (10,11), and several studies have documented involvement in the criminal justice system of patients in assertive community treatment or intensive case management programs (12,13,14,15). However, little attention has been focused on the broader issue of involvement in the criminal justice system among patients receiving services from entire health care systems—that is, a population-based approach.

The finding that large numbers of detainees have mental illness may mean that incarceration is an indicator of treatment failure at the level of individual clinical programs or of entire service systems. Pandiani and associates (15) used incarceration rates to evaluate the performance of ten community support programs in Vermont. The study reported here extends this approach to compare population-based frequency of incarceration among users of various mental health systems; to identify specific risk factors for incarceration among such patients; and to determine whether inpatient bed closures were associated with changes in rates of incarceration. If incarceration is frequent in vulnerable populations, monitoring rates of incarceration among clients of specific providers may be useful as a measure of quality of care or as an indicator of the adverse impact of changes in patterns of service delivery or in the availability of treatment resources.

The lack of data on incarceration among mental health service users is largely due to concerns about client confidentiality. These concerns often prohibit the sharing of administrative data that disclose unique client identifiers—for example, Social Security numbers—between mental health service providers and the criminal justice system (16). Survey data based on direct interviews could be used to assess recent criminal justice system involvement, but such data are likely to be biased by underreporting (12) and are costly to obtain on a large scale.

In this study we used probabilistic population estimation, a novel statistical technique that provides estimates of overlaps of populations based exclusively on the distribution of birth dates in different datasets, without relying on specific patient identifiers. We used this approach to estimate incarceration rates among users of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) behavioral health services in 16 counties in northeastern New York State between 1994 and 1997—a time of substantial change in VA during which approximately one-third of inpatient mental health beds were closed across the VA system nationally (17). We also examined incarceration rates for different diagnostic groups of VA patients. Finally, we compared rates of incarceration among patients hospitalized for mental illness in VA facilities, in general hospitals, and in state hospitals between 1994 and 1996.

Methods

Subjects

Comprehensive data were collected for the years 1994 through 1997 for all adult male users of VA behavioral health services programs and for all men incarcerated in 16 counties in northeastern New York state. The counties are Albany, Allegheny, Chemung, Chenango, Columbia, Cortland, Essex, Franklin, Greene, Herkimer, Jefferson, Lewis, Otsego, Schenectady, Steuben, and Washington. For the purposes of comparison, data were collected for all men who received inpatient behavioral health care services in general hospitals and state mental hospitals in the same counties between 1994 and 1996.

Data on the VA sample were extracted from two computerized national workload files: the patient treatment file, which is a discharge abstract file that documents all episodes of VA hospital care, and the outpatient care file, a workload file that documents all VA outpatient service use. Service codes and residence zip codes in these files allowed identification of all users of VA psychiatric services, substance abuse services, or both types of services—that is, dual diagnosis patients—during each year. Over the four-year study period, data were obtained on 5,603 male VA system users, including 5,445 users of outpatient services and 1,682 users of inpatient services.

Data on persons incarcerated in local jails were obtained from correctional authorities for the 16 counties. A total of 44,783 episodes of incarceration involving an unduplicated total of 27,869±728 adult male residents between 1994 and 1997 were described in this file. All unique personal identifiers except date of birth were stripped from the incarceration files by the agencies responsible for the files. The procedure for determining the unduplicated number of people represented in this dataset is described below.

Data on users of inpatient behavioral health services in general hospitals were obtained from the New York State Department of Health. These data describe 15,510 episodes of hospitalization involving 9,039±115 male patients in the study area who were hospitalized for psychiatric disorders in general hospitals between 1994 and 1996. The procedure for determining the unduplicated number of people represented in this dataset is described below.

Data on inpatients of state mental hospitals in the 16 counties were obtained from the New York Office of Mental Health. This file included 1,896 computer records that described episodes of hospitalization for 1,321 male patients who were hospitalized for psychiatric disorders in state mental hospitals in the study area between 1994 and 1996.

Statistical method

Estimation of overlap between the samples was based entirely on probabilistic population estimation, a statistical procedure that was developed to facilitate the use of existing operational and administrative datasets for mental health service systems research. The procedure, its derivation, and validation studies are described in detail elsewhere (16,18,19). This method addresses the question of how many individuals in datasets from two organizations are served by both of them. The following paragraphs describe the application of this procedure in the current study and demonstrate the precision and validity of the estimates.

In order to derive estimates of the number of individuals represented in the criminal justice and the general hospital datasets, each dataset was broken into smaller data subsets in which all records listed the same year of birth—for example, all records in the subset were for men born in 1945. The number of distinct birthdays that occurred in each data subset was counted. The number of persons necessary to produce the observed number of birthdays was calculated using the formula where Pj is the population estimate for subset j, and lj is the number of birthdays observed in the year. Confidence intervals for the estimate were calculated using a similar procedure. Estimates of the total number of individuals represented in the complete dataset and the confidence intervals for this estimate were obtained by combining the results for every year-of-birth cohort in the original dataset. Because this procedure uses the number of dates of birth represented in a dataset rather than the number of records in the dataset, the dataset may include multiple records for a single individual—for example, event or episode records.

where Pj is the population estimate for subset j, and lj is the number of birthdays observed in the year. Confidence intervals for the estimate were calculated using a similar procedure. Estimates of the total number of individuals represented in the complete dataset and the confidence intervals for this estimate were obtained by combining the results for every year-of-birth cohort in the original dataset. Because this procedure uses the number of dates of birth represented in a dataset rather than the number of records in the dataset, the dataset may include multiple records for a single individual—for example, event or episode records.

In order to probabilistically determine the number of individuals shared across datasets that do not use unique person identifiers, the sizes of three populations are determined, and the results are compared. First, the number of persons represented in the dataset that describes each of the service sectors is determined. In this study, the datasets came from a behavioral health service system and a criminal justice system. A third dataset is formed by combining the two original datasets and determining the number of individuals represented in the combined dataset. In this study, the number of individuals represented in the original and the combined (concatenated) datasets were determined using probabilistic population estimation.

The number of individuals who are shared by the two datasets is the difference between the sum of the numbers of people represented in the two original datasets and the number of people represented in the combined dataset. This result occurs because the sum of the number of people represented in the two original datasets will include a double count of every person who is represented in both datasets. The number of individuals represented in the combined dataset does not include this duplication. The difference between these two numbers is the size of the duplication between the two original datasets, the size of the caseload overlap.

Because the VA datasets included a unique person identifier, it was possible to compare actual unduplicated counts of the number of persons represented in these datasets with the probabilistic estimates of the number of individuals represented. Table 1 presents the results of this comparison for three diagnostic groups and for the population of VA clients overall. In every case, the probabilistic estimate was within 1 percent of the true value, and the 95 percent confidence interval of the estimate included the true value in every case. In a larger demonstration, the 95 percent confidence interval would include the true value in 19 of every 20 demonstrations.

Results

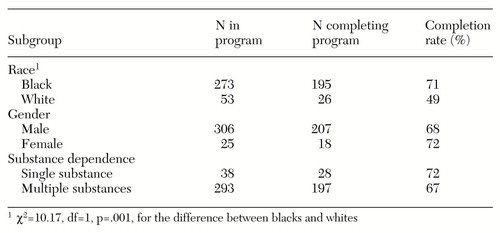

As Table 2 shows, of the 5,603 adult males who used VA behavioral health service between 1994 and 1997, a total of 15.7 percent were also incarcerated at some time during that period. Among patients age 18 to 39 years, the incarceration rate was 39.6 percent; among those age 40 years and older, the rate was 9.1 percent. Estimated rates of incarceration were similar among inpatients and outpatients, with a trend toward higher rates of incarceration among inpatients. Dual diagnosis patients had the highest rates of incarceration (25.2 percent), followed by patients with substance abuse problems only (21.2 percent) and those with psychiatric problems only (11.4 percent).

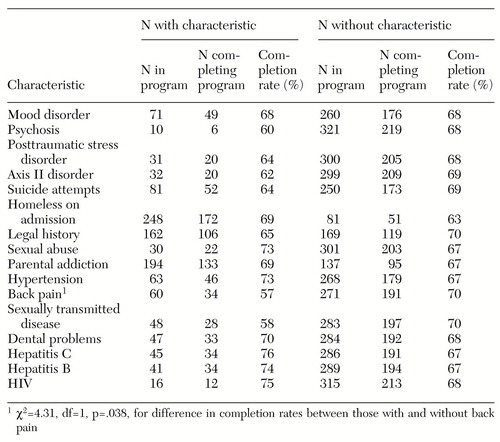

Table 3 shows the incarceration rates among patients in the three service systems and the general population. The overall rate of incarceration among patients hospitalized in VA facilities (11.6 percent) was lower than the rates among patients in general hospitals (23 percent) and in state hospitals (21.7 percent). Among patients age 18 to 39 years, rates of incarceration—20 to 30 percent—were similar across health care systems. Older patients in state hospitals were more likely to have been incarcerated (23.7 percent) than older patients in general hospitals (12.6 percent) or VA medical centers (8.3 percent). The odds ratios in Table 3 indicate that incarceration rates were two to four times greater among hospitalized patients than among the general population (the reference group) and were four to 12 times higher among older patients.

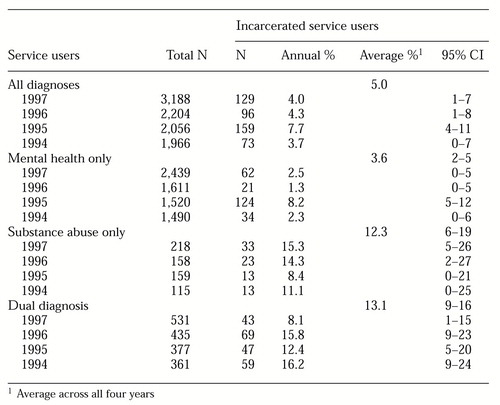

As Table 4 shows, the average annual rate of incarceration for VA patients during the four-year study period was 5 percent, with a rate of 3.6 percent among mental health patients, 12.3 percent among substance abuse patients, and 13.1 percent among dual diagnosis patients. Incarceration rates showed little variability over the four years, and there was no evidence of significantly increased incarceration for any particular diagnostic group.

Discussion

This study documented substantial incarceration among users of inpatient and outpatient VA behavioral health services in northeastern New York State between 1994 and 1997; however, incarceration rates among this population were not substantially different from those of persons who received inpatient behavioral health services in other sectors. Annual incarceration rates among users of VA services did not change during this four-year period, a time of significant bed closures in VA facilities.

Altogether, more than 15 percent of all male VA mental health patients and almost 40 percent of those age 18 to 39 years were incarcerated at some time in the study period. The highest risk for incarceration was among the dual diagnosis patients (25 percent) followed by patients with substance abuse problems alone (21 percent) and those with psychiatric problems alone (11 percent). For younger patients, the incarceration rates of hospitalized patients in VA facilities, general hospitals, and state hospitals were similar. Among older patients, those in state hospitals were more likely to have been incarcerated.

Study limitations

Several methodological limitations of this study require comment. First, the probabilistic estimates of population overlap tend to include wide confidence intervals when populations are of vastly different sizes. In this case, most of the incarcerated persons were younger than 40 years, and most of the veterans were older than 40 years. This type of discrepancy results in a needle-in-the-haystack problem for the statistical methodology.

It should be noted, however, that alternative methods can also provide wide confidence intervals. Standard sample survey methods would need to obtain usable responses from at least 1,000 recipients of inpatient behavioral health services in the 16 counties studied in order to obtain similar confidence intervals. Issues of the representativeness of samples and response bias, the validity of responses, and the cost associated with original data collection would remain.

Nevertheless, the wide confidence intervals produced by this analysis limit our ability to employ multivariate analysis of risk factors for incarceration. Although we can identify increased risk of incarceration among younger patients and among those with substance abuse disorder, we cannot determine whether these observations are attributable to the fact that younger patients are also more likely to have a substance use problem.

Second, it is possible that although no increase in incarceration among VA system users was shown, some patients may have dropped out of the system altogether and have been incarcerated as a result of lack of treatment. We think this development is unlikely because, despite reduced availability of inpatient treatment in VA facilities, the number of veterans who received inpatient or outpatient mental health treatment from the VA system increased steadily over the years covered by this study (see Table 4).

Third, data on rates only of incarceration are available here. Encounters with the criminal justice system without either arrest or incarceration are far more common than incarceration (12). However, incarceration represents a very serious level of involvement and thus is a suitable indicator of treatment failure.

Fourth, it is possible that other systems increased their bed availability and VA patients found other sources of hospital care. However, a similar study of cross-system use of hospital care found that both VA and non-VA bed capacity declined, and there was no increased use of non-VA hospital care by VA patients (20).

A final limitation is our use of data from a limited geographic area. The generalizability of our results to other localities is unknown.

Risk factors

This study examined some risk factors for incarceration of male mental health service users at both the individual client level and the service system level. The observation that youth, mental illness, and substance abuse are major risk factors for incarceration among men receiving mental health services is consistent with findings from studies based on community surveys (1,6) and incarcerated populations (12) and confirms these findings.

The general similarity in rates of incarceration among younger patients hospitalized in VA and non-VA service systems suggests general comparability of risk among younger hospitalized patients. The growing use of utilization review procedures and the use of both general hospitals and state mental hospitals as well as VA medical centers to care for indigent people with severe mental illness most likely account for the increased homogeneity of patients treated in these three settings in recent years.

The large proportion of older patients who were admitted to state hospitals and who were incarcerated, compared with the proportions admitted to VA facilities and to general hospitals, is more difficult to explain. Compared with the general population of similar age, older state hospital patients were at greater risk for incarceration than any other subgroup examined in this study. This finding may reflect incarceration of people with marginal community existences who are at high risk of incarceration because they lack residential alternatives.

Regarding the concern that rapid changes in public and private mental health systems in recent years may have adversely affected vulnerable people with mental illness (21,22,23,24,25), we found no greater risk of incarceration among patients hospitalized in VA facilities in 1997 than in 1994, despite substantial VA bed closures during these years. For reasons specified above, the data presented here do not allow us to conclude that bed closures had no adverse effect on VA patients.

Incarceration is a crude indicator of adverse effect, albeit one that is frequently referred to in casual conversation about the plight of the mentally ill population. This study is the first of which we are aware that empirically examined rates of incarceration as a potential indicator of the adverse effects of bed reductions, and our findings were negative. Although we found no evidence of such effects, it is possible that VA patients obtained supplementary outpatient treatment to make up for reduced access to VA hospital care, or that bed closures resulted in adverse effects other than incarceration, such as suicide or homelessness. Further studies are under way to examine these possibilities.

Conclusions

Although this study found that substantial numbers of users of VA mental health services were incarcerated between 1994 and 1997, the risk of incarceration was similar to that of users of other health care systems and did not increase in association with the closure of inpatient beds. The study illustrates both the potential value and the limitations of this indicator of adverse effects of system change.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Lucille M. Schacht, M.S., to data management and analysis.

Dr. Rosenheck and Dr. Hoff are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Connecticut-Massachusetts Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center in West Haven, Connecticut, and the departments of psychiatry and public health at Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Banks and Dr. Pandiani are affiliated with the Bristol Observatory in Bristol, Vermont. Dr. Banks is also affiliated with the New York State Office of Mental Health in Albany. Send correspondence to Dr. Rosenheck, VA Connecticut Health Care System (182), 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516-2770 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

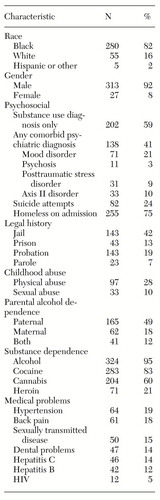

Table 1. Actual population sizes and probabilistic estimates of user populations of Veterans Affairs behavioral health services from 1994 to 1997

|

Table 2. Estimated rates of incarceration among users of Veterans Affairs behavioral health service from 1994 to 1997

|

Table 3. Incarceration rates across three service system populations and in the general population from 1994 to 1996

|

Table 4. Estimated rates of incarceration among users of both inpatient and outpatient Veterans Affairs behavioral health service from 1994 to 1997

1. Teplin L: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663-669, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Teplin L: Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. American Journal of Public Health 84:290-293, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, et al: Chronic mental illness and the criminal justice system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:718-723, 1988Google Scholar

4. Jail Inmates 1992. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1993Google Scholar

5. Torrey EF, Stieber J, Ezekial J: Criminalizing the Mentally Ill: The Abuse of Jails as Mental Hospitals. Washington, DC, Public Citizens' Health Research Group and National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1992Google Scholar

6. Teplin L: The criminalization of the mentally ill: speculation in search of data. Psychological Bulletin 94:54-67, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Steadman HJ, Morris SM, Dennis DL: The diversion of mentally ill persons from jails to community-based services: a profile of programs. American Journal of Public Health 85:1630-1635, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Barbera SS, Dennis DL: A national survey of jail diversion programs for mentally ill detainees. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1109-1113, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Hoff RA, Baranosky MV, Buchanan J, et al: The effects of a jail diversion program on incarceration: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 27:377-386, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

10. Harry B, Steadman HJ: Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services 39:862-866, 1988Link, Google Scholar

11. Taylor P: Schizophrenia and crime: distinctive patterns in association, in Mental Disorder and Crime. Edited by Hodgins S. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

12. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GO: Legal system involvement and costs for persons in treatment for severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:641-647, 1999Link, Google Scholar

13. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152-165, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Solomon P, Draine J, Meyerson A: Jail recidivism and receipt of community mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:793-797, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Using incarceration rates to measure mental health program performance. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:300-311, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Personal privacy versus public accountability: a technological solution to an ethical dilemma. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:456-463, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck RA, Dilella D: National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 1997 Report, West Haven, Conn, Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1998Google Scholar

18. Banks SM, Pandiani JA: Probabilistic population estimation of the size and overlap of data sets based on date of birth. Statistics in Medicine, in pressGoogle Scholar

19. Banks SM, Pandiani JA: The use of state and general hospitals for inpatient psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 88:448-451, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck RA, Banks S, Pandiani J: Does closing beds in one public mental health system result in increased use of hospital services in other systems? Mental Health Services Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

21. Leslie D, Rosenheck RA: Changes in inpatient mental health utilization and cost in a privately insured population:1993-1995. Medical Care 37:457-468, 1999Google Scholar

22. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Inpatient treatment of comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders: a comparison of public sector and privately insured populations. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 26:253-268, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Shifting to outpatient care? Mental health utilization and costs in a privately insured population. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1250-1257, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Ma C, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health care carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

25. Popkin MK, Lurie N, Manning W, et al: Changes in process of care for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia in Utah's prepaid mental health plan. Psychiatric Services 49:518-523, 1998Link, Google Scholar