Prevalence of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Those With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Individuals with serious mental illness have elevated smoking rates, and smoking is a significant risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The goal was to determine the prevalence of COPD among those with serious mental illness. METHOD: The authors surveyed a random sample of 200 adults with serious mental illness with questions from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study III that were previously used to estimate the national prevalence of COPD. They compared the prevalence of COPD in the sample to a randomly selected matched subset of national comparison subjects. RESULTS: The prevalence of COPD was 22.6%. Those with serious mental illness were significantly more likely to have chronic bronchitis (19.5% versus 6.1%) and emphysema (7.9% versus 1.5%) than the comparison subjects. CONCLUSIONS: The prevalence of COPD is significantly higher among those with serious mental illness than comparison subjects. Improved primary and secondary prevention is warranted.

People with serious mental disorders are more than twice as likely to smoke relative to the overall adult population (1–3). Because chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) accounts for nearly 60% of all smoking-attributable disease (4), individuals with serious mental disorders are likely to be at high risk for developing this disease. Some studies have reported that individuals with schizophrenia have higher mortality rates from all respiratory diseases than the general population (5, 6); however, to our knowledge, there are no studies that report the prevalence of COPD among individuals with serious mental illness.

The goal of our study was to determine the prevalence of COPD in a sample of individuals with serious mental illness and compare this prevalence to the prevalence of COPD among a matched group of national comparison subjects.

Method

Our study of somatic comorbidity has been previously described (7, 8). We used a cross-sectional design to survey outpatients receiving psychiatric care at the University of Maryland in Baltimore and Sheppard Pratt Health System. Participants were selected in order to obtain 50 subjects with schizophrenia, 50 with schizoaffective disorder, 50 with recurrent major depressive disorder, and 50 with bipolar affective disorder. Within each diagnostic group, patients were selected in random order until the predetermined number of consenting patients was obtained. Interview items were drawn from the National Health Interview Survey, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The interviews were conducted in the period from March to December 2000. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Sheppard Pratt Health System. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Seventy-three percent (N=200) of 275 eligible individuals provided informed consent and completed an in-person interview. Individuals were paid $15 for participation in the study.

Individuals who answered “yes” to the following question from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III survey—“Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had 1) chronic bronchitis or 2) emphysema?”—were defined as having COPD. These exact questions have been used in published reports to estimate the prevalence of COPD in the general population (9). Individuals who answered “yes” to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had asthma?” were defined as having asthma. Individuals who answered “yes” to the question, “Are you currently being treated for 1) chronic bronchitis or 2) emphysema?” were defined as receiving treatment for these conditions. Individuals who answered “yes” to both the following questions—1) “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes (approximately 5 packs) during your entire lifetime?” and 2) “Do you smoke cigarettes now?”—were defined as current smokers.

We calculated percentages for dichotomous responses, including our primary outcome of interest, the prevalence of COPD, and means with standard deviations for continuous variables.

Separate univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify individual variables significantly associated with having COPD. We considered variables known to be associated with COPD among individuals in the general population, including age, gender, and smoking status.

We compared the study group with a randomly selected subset from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III survey data set. The study sample was stratified into groups by age, race, and gender. For each individual in a group, 15 matches were selected without replacement from the corresponding group in the national data set with SAS software. The study group was divided into 3-year age groups for matching. We were unable to appropriately match the race of six Asian Pacific Islanders, five Native Americans, and four “other” ethnic categories to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data set. This left 185 subjects in the matched data set. The matched data sets included 185 of the 200 items from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. A total of 2,891 individuals comprised the total group for the comparisons with items from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III.

Because we did not find any significant differences in the prevalence of COPD when we stratified the group by diagnosis, we present the prevalence for the entire group—those with serious mental disorders.

Results

The mean age of the 200 subjects was 44.0 years (SD=8.9). Over half were women (N=105, 52.5%), 112 (56.0%) were Caucasian, 96 (48.5%) reported being married, and 145 (72.9%) reported having a high school degree.

The prevalence of current smoking was 121 of 199 (60.5%). Among current smokers, 28 of 121 (23.1%) reported quitting smoking for a year or longer.

With respect to use of medical health care, 176 of 200 (88%) reported having a regular place to go when they were sick or needed advice about their health.

The prevalence of COPD was 22.6%: 39 of 199 (19.6%) reported having chronic bronchitis, 15 of 200 (7.5%) reported having emphysema, and nine of 200 (4.5%) reported having both. The prevalence of asthma was 18.5%. Among those reporting a diagnosis of COPD, 15 of 45 (33.3%) also reported having asthma.

Independent predictors associated with having a diagnosis of COPD included age (adjusted odds ratio=1.04, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.00–1.10, p<0.04), being male (adjusted odds ratio=3.52, 95% CI=1.52–8.15, p=0.003), and being a current smoker (adjusted odds ratio=8.83, 95% CI=1.98–39.34, p=0.004). Of those who reported having COPD, 16 of 45 (35.6%) reported receiving treatment for this condition.

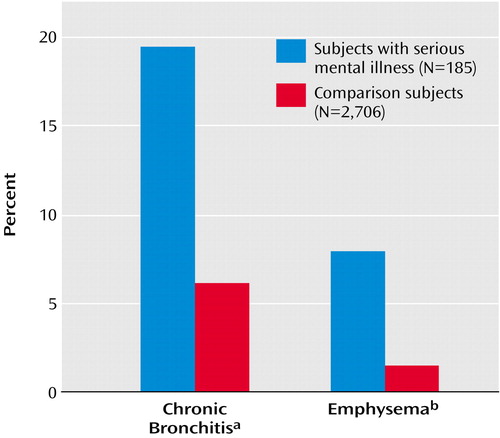

Compared to national comparison subjects who were matched on age, gender, and race, those with serious mental illness were significantly more likely to report a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (19.5% versus 6.1%) (χ2=35.5, df=1, p<0.0001; crude odds ratio=3.75, 95% CI=2.53–5.55) as well as emphysema (7.9% versus 1.5%) (χ2=38.8, df=1, p<0.0001; crude odds ratio=5.69, 95% CI=3.08–10.48) (Figure 1).

Discussion

Individuals with serious mental illness in our study had over three times the odds of having chronic bronchitis and over five times the odds of having emphysema than a matched group of national comparison subjects. Overall, the reported prevalence of COPD among those with serious mental illness in our study was 22.6%. This compares to a reported prevalence of 5% for COPD in the general population for a similar age group (9). We also found a considerable overlap between COPD and asthma, which is true for the general population as well (10). Consistent with previous research, we found the prevalence of current smoking to be 60.5%, which is more than twice the average in Maryland (27.4%) (11) and nationally (22.6%). Not surprisingly, smoking was the strongest independent predictor of COPD, with smokers having over eight times the odds of having COPD than the nonsmokers in our group.

We also found that a third of the individuals with COPD reported being treated for this condition. However, because we were unable to compare our results to the general population, we were not able to determine whether this is a deviation from treatment of COPD in the general population.

Our study did have limitations. First, our definition of COPD was based on self-reports without confirmation from spirometry or medical records review. However, the questions we used to define an individual as having COPD were taken from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III and have been used in published reports to estimate the prevalence of COPD for the general population (9). Our estimates were likely to underestimate the true prevalence as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III reported that 63% of respondents who had documented low lung volume (forced expiratory volume in 1 second less than 80% predicted) when tested with spirometry did not self-report a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12). This underscores the need to include spirometry in any future studies. Second, the study group was derived from Baltimore and may not generalize to the U.S. population as a whole. Third, this study was a cross-sectional design, so we were able to identify only associations and not causations. Fourth, we may not have been able to control for potential residual confounders (e.g., socioeconomic status) that may have led to a biased estimate of COPD.

COPD has been called the “silent epidemic” and is the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S. general population. This “epidemic” seems to be even more silent among individuals with serious mental illness who are at particular risk of developing this condition from smoking, which is a modifiable risk factor. This highlights the need for improved primary and secondary interventions targeted at smoking cessation as well as a campaign to increase awareness among primary care providers and mental health specialists to screen for this condition.

Received Jan. 15, 2004; revisions received March 26 and April 14, 2004; accepted May 14, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Services Research, and the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine; and the Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. Address reprint requests to Dr. Himelhoch, Department of Psychiatry, Division of Mental Health Services Research, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 685 West Baltimore St., MSTF Building, Suite 300, Baltimore, MD 21201-1549; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the National Association or Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Dr. Dixon, principal investigator) and by the University of Maryland Statewide Health Network/Other Tobacco-Related Diseases Grant (Dr. Lehman, principal investigator). Dr. Daumit was supported by NIMH grant K08-MH-01787, and Dr. Kreyenbuhl was supported by NIMH grant KO1-MH-066009-02.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema in Subjects With Serious Mental Illness Compared to a Matched Group of National Comparison Subjects

aSignificant difference between subjects with respect to prevalence of chronic bronchitis (χ2=35.5, df=1, p<0.0001).

bSignificant difference between subjects with respect to prevalence of emphysema (χ2=38.8, df=1, p<0.0001).

1. Chiles JA, Cohen S, Maiuro R: Smoking and schizophrenic psychopathology. Am J Addict 1993; 2:315–319Crossref, Google Scholar

2. de Leon J, Dadvand M, Canuso C, White AO, Stanilla JK, Simpson GM: Schizophrenia and smoking: an epidemiological survey in a state hospital. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:453–455Link, Google Scholar

3. Lasser K, Wesley Boyd J, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bohr D: Smoking and mental illness a population based prevalence study. JAMA 2000; 284:2606–2610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hyland A, Li Q, Giovino GA, Yang J, Cummings KM: Cigarette Smoking-Attributable Morbidity by State. Buffalo, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, 2003, pp 1–5Google Scholar

5. Buda M, Tsuang MT, Fleming JA: Causes of death in DSM-III schizophrenics and other psychotics (atypical group): a comparison with the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:283–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Joukamaa M, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Raitsalo R, Lehtinen V: Mental disorders and cause-specific mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179:498–502Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dickerson FB, McNary SW, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl J, Goldberg RW, Dixon LB: Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Med Care 2003; 441:560–570Google Scholar

8. Sokal J, Messias E, Dickerson F, Kreyenbuhl J, Brown CH, Goldberg RW, Dixon LB: Comorbidity of medical illnesses among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:421–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance—United States, 1971–2000. Respir Care 2002; 47:1184–1199Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E: Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:1683–1689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation Program: First Annual Tobacco Study Cigarette Restitution Fund Program. Baltimore, State of Maryland, 2002, pp 1–50Google Scholar

12. Cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:842–844Medline, Google Scholar