The Volume-Quality Relationship of Mental Health Care: Does Practice Make Perfect?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: An extensive literature has demonstrated a relationship between hospital volume and outcomes for surgical care and other medical procedures. The authors examined whether an analogous association exists between the volume of mental health delivery and the quality of mental health care. METHOD: The study used data for the 384 health maintenance organizations participating in the Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS), covering 73 million enrollees nationwide. Analyses examined the association between three measures of mental health volume (total annual ambulatory visits, inpatient discharges, and inpatient days) and the five HEDIS measures of mental health performance (two measures of follow-up after psychiatric hospitalization and three measures of outpatient antidepressant management), with adjustment for plan and enrollee characteristics. RESULTS: Plans in the lowest quartile of outpatient and inpatient mental health volume had an 8.45 (95% CI [confidence interval]=4.97–14.37) to 21.09 (95% CI=11.32–39.28) times increase in odds of poor 7- and 30-day follow-up after discharge from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Low-volume plans had a 3.49 (95% CI=2.15–5.67) to 5.42 (95% CI=3.21–9.15) times increase in odds of poor performance on the acute, continuation, and provider measures of antidepressant treatment. CONCLUSIONS: The large and consistent association between mental health volume and performance suggests parallels with the medical and surgical literature. As with that previous literature, further work is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying this association and the potential implications for using volume as a criterion in plan choice.

Since Luft et al. (1) first documented an inverse relationship between the number of procedures performed in a hospital and mortality, the positive association between volume of care delivery and outcomes of care has been documented across a variety of settings and health conditions (2, 3). The strength and consistency of this association has led organizations such as the Leapfrog group to recommend referral of patients to high-volume hospitals for a range of surgical and medical procedures (4).

This study examines whether a parallel association exists between the volume of mental health delivery and mental health performance for plans participating in the Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS), the most widely used health plan report card in the United States (5). We tested whether, or to what degree, plans that deliver more mental health services also perform better on mental health quality indicators.

Method

The study used data from HEDIS 2000, comprising 1999 performance data from 384 plans covering 73 million enrollees nationwide. All analyses included both reporting and nonreporting plans (6).

Volume Measures

The vast majority of previous examinations of the volume-outcome relationship—88.6% in one review (7)—examined hospital-level indicators of volume. These hospital-level indicators have been used because they reflect the capacity to treat specialized conditions and because, in the absence of physician identifiers, they are used as proxies for clinician volume. While previous studies have not examined these associations for health plans, analogous mechanisms would be expected to apply, particularly for health maintenance organizations (HMOs), that by definition are both insurers and providers of care (8).

For the current study, the National Center for Quality Assurance provided three measures of volume of mental health services. A first outpatient measure examined the total annual number of plan members using any ambulatory mental health services during the study year. Two others examined inpatient volume of care in the study year: the total number of members with an inpatient mental health hospitalization and the total number of inpatient mental health days.

Performance Measures

The volume/outcome relationship has almost exclusively been studied for acute, life-threatening conditions in which mortality serves as a fairly reliable indicator of successful or unsuccessful treatment. However, for mental disorders, like other chronic conditions, mortality is rare, and other clinical outcomes, such as symptoms, are expensive and time consuming to measure on a routine basis. Thus, HEDIS, like other general health and mental health report card systems (9, 10), relies primarily on process measures rather than outcomes measures to assess quality.

HEDIS 2000 included five mental health quality measures (11). Two indicators of follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness assessed the percentage of members hospitalized for a mental disorder with a mental health visit within 7 and 30 days of hospital discharge. Three measures assessed the appropriateness of antidepressant medication management. The first—effective treatment in the acute phase—assesses the percentage of adult members diagnosed with a new episode of depression and given an antidepressant drug who had prescriptions filled for a continuous trial of medication treatment during the 12-week period after initiation of the treatment. The second—effective continuation treatment—represents the percentage of adult members diagnosed with a new episode of depression and given an antidepressant who continued to have prescriptions filled for an antidepressant for at least 6 months after beginning the medication. The third—optimal practitioner contacts—represents the percentage of adult members diagnosed with a new episode of depression with at least three mental health follow-up visits (with either a primary care physician or mental health practitioner) in the 12 weeks after diagnosis.

Other Variables

Several other plan-level variables were used both for descriptive purposes and as control variables in multivariate analyses. These included the proportion of members who were women; the proportion of enrollees in each of four age groups; the percentage of enrollees with Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial insurance; and the plan’s geographical location.

Analytic Strategy

A first set of analyses provided descriptive statistics on each of the key independent and dependent variables. In keeping with the strategy used in most of the previous volume/outcome literature (7), dichotomous variables were created for each of the quality and volume indicators, dividing the bottom quartile from the remainder of the study group. Logistic regression was used to model the association between the bottom quartile of performance on each mental health quality measure and the bottom quartile of each of the volume measures, with adjustment for the mean age and the proportion of women in the plan, the public-private mix of enrollees, and the proportion of enrollees in each of eight U.S. geographic regions. SAS version 8.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 384 plans, representing 90% of all individuals enrolled in U.S. HMOs (5), participated in HEDIS 2000. Enrollee and plan characteristics, inpatient and outpatient mental health volume, and performance measures are reported in Table 1.

In multivariate models with adjustment for enrollee plan characteristics, plans with a low volume of mental health care had substantially lower mental health performance ratings on both of the two measures of follow-up after discharge (Table 2). Plans with a low volume of ambulatory mental health visits were 13.63 (95% confidence interval [CI]=7.66–24.24) times more likely to have poor follow-up within 7 days of discharge from mental health hospitalization and 21.09 (95% CI=11.32–39.28) times more likely to have poor follow-up in the 30 days after discharge from mental health hospitalization. Plans with the lowest volume of inpatient mental health use were 8.45 (95% CI=4.97–14.37) to 14.68 (95% CI=8.04–26.80) times more likely to perform poorly on those two measures of inpatient follow-up.

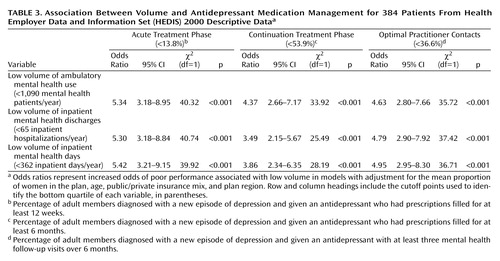

Low-volume plans also had considerably lower performance on the HEDIS acute, continuation, and optimal practitioner measures of antidepressant management. Low volume of ambulatory mental health service use was associated with a 4.37 times (95% CI=2.66–7.17) increase in odds of poor performance on these three indicators (Table 3). Similarly, low volume of inpatient mental health service use was associated with a 3.49 times (95% CI=2.15–5.67) to 5.42 times (95% CI=3.21–9.15) increase in odds of poor performance on the antidepressant management measures.

Discussion

HMOs with lower inpatient and outpatient volumes of care were consistently and substantially more likely to perform poorly on the HEDIS mental health performance measures. The literature on volume and outcomes of medical care can provide a useful context for understanding the potential explanations for—and implications of—these findings.

Low Volume of Care and Poor HEDIS Performance

Two primary hypotheses have been posited for explaining the volume/outcome relationship in acute medical care—“selective referral” and “practice makes perfect” (12). Under the first scenario, plans with a reputation for high quality of care would attract more enrollees: quality would drive volume of service delivery. Unfortunately, in today’s health market, it is relatively uncommon for purchasers and consumers to use quality indicators, particularly mental health measures, in choosing their coverage (13, 14). Thus, while quality-based purchasing represents an important goal, it is not likely to be the primary explanation for the volume/performance association observed in this study.

The mechanism most frequently invoked as explaining the volume/outcome relationship in medical and surgical care is the notion that “practice makes perfect.” Surgeons that perform more coronary bypass operations have lower mortality rates, even after adjustment for severity of illness, likely as a result of their greater experience (15). Intensive care units with high daily censuses are particularly successful at managing high-risk deliveries, presumably because of their ability to offer highly specialized services (16). A recent study suggested a complex relationship between clinical-level and hospital-level volume that varies across differing procedures (17).

One might expect that many of the same principles underlying the volume/outcomes association in medical and surgical care would apply to the delivery of mental health services. For a particular clinician, experience in interventions ranging from psychopharmacology to psychotherapy might be expected to lead to greater proficiency. Indeed, this may be one way of understanding the finding that patients treated by specialty mental health providers are more likely to receive guideline-concordant care than those treated by primary care physicians (18). Because the current study examined only plan-level associations, it will be important for further research to examine whether these patterns are also evident at the level of individual clinicians.

For mental health organizations, there may also be benefits to specialization. Psychiatric clinics and inpatient units are often organized by diagnoses (e.g., schizophrenia) or needs (e.g., homeless clinics) to provide expertise and specialized services. A central argument for “carving out” mental health care has been that it allows for economies of scale that cannot be provided through general medical plans (19).

However, specialization also brings potential pitfalls. Geographic consolidation of services, such as ECT, can raise barriers to access (20); proliferation of subspecialists may lead to fragmentation (21). The challenge facing any mental health system is how to capture the benefits of specialized, “high-volume” services while ensuring appropriate access to—and integration among—those services.

A critical issue in determining the appropriate balance between specialization and integration is what a recent Institute of Medicine report termed the “volume of what?” question (7). For instance, it is not known how much of the volume-outcome association seen for carotid endarterectomies can be explained by experience with that particular procedure, experience in a specialized subset of those operations, or more general experience in surgical vascular procedures. In the current study, the large and consistent associations across different measures and domains suggest that the mechanisms linking volume and quality may be relatively nonspecific. Indeed, the broadest and largest associations were seen for the two measures of follow-up after hospitalization, which span both inpatient and outpatient mental health care. High inpatient or outpatient volume is likely to reflect more—and more experienced—mental health staff, as well as greater experience in administratively managing mental health care. Again, more work is needed to better delineate the precise mechanisms linking specific dimensions of volume to mental health performance.

Limitations

The study’s findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Data were available only at the plan level rather than at the provider level, limiting the ability to determine how many of the observed associations reflect higher-volume clinicians or characteristics of the higher-volume plans. HEDIS performance measures are relatively crude proxies for mental health quality, covering only a limited range of domains and providing no information on clinical outcomes. Finally, the fact that both the volume measures and performance indicators rely on service use data makes it difficult to fully disentangle these two domains. Further work would benefit from the use of prospectively collected data, volume information for both providers and plans, and quality assessment that includes both process and clinical outcome measures, such as symptom profiles. It may be particularly useful to examine this relationship for more specifically defined procedures and populations, such as the case of ECT in severe depression.

Implications

Given these limitations, we regard the results of the study as exploratory rather than definitive. Although it is still premature to recommend that purchasers choose mental health coverage based on plans’ mental health volume, we hope that the study’s findings will encourage others to further explore this volume/quality framework in mental health. Understanding when and how greater experience leads to better care may ultimately prove an important tool for improving that care. As Hall of Fame Football Coach Vince Lombardi famously remarked, “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.”

|

|

|

Received Aug. 14, 2003; revision received Oct. 27, 2003; accepted Feb. 18, 2004. From the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University; Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh; RAND, Pittsburgh; and the Office of Research, National Center for Quality Assurance, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Druss, Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd., NE, Rm. 606, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded in part by NIMH grant K08-MH-01556.

1. Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC: Should operations be regionalized? the empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med 1979; 301:1364–1369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hewitt M: Interpreting the Volume-Outcome Relationship in the Context of Health Care Quality: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, 2000Google Scholar

3. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, Welch HG, Wennberg DE: Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1128–1137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, Salber P, Buck CR Jr: Improving the safety of health care: the Leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract 2000; 3:313–316Medline, Google Scholar

5. National Center for Quality Assurance: The State of Managed Care Quality 2000. Washington, DC, NCQA, 2000Google Scholar

6. McCormick D, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Wolfe SM, Bor DH: Relationship between low quality-of-care scores and HMOs’ subsequent public disclosure of quality-of-care scores. JAMA 2002; 288:1484–1490Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR: Appendix C: how is volume related to quality in health care? a systematic review of the research literature, in Interpreting the Volume-Outcome Relationship in the Context of Health Care Quality: Workshop Summary. Edited by Hewitt M. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, 2000, pp 27–62Google Scholar

8. Robinson JC: The Corporate Practice of Medicine. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1999Google Scholar

9. Hermann RC, Leff HS, Palmer RH, Yang D, Teller T, Provost S, Jakubiak C, Chan J: Quality measures for mental health care: results from a national inventory. Med Care Res Rev 2000; 57(suppl 2):136–154Google Scholar

10. Brook R, McGlynn EA, Cleary P: Quality of health care, part 2: measuring quality of care. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:966–970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Druss BG, Miller CL, Rosenheck RA, Shih SC, Bost JE: Mental health care quality under managed care in the United States: a view from the Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:860–862Link, Google Scholar

12. Luft HS, Hunt SS, Maerki SC: The volume-outcome relationship: practice-makes-perfect or selective-referral patterns? Health Serv Res 1987; 22:157–182Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rost K, Smith J, Fortney J: Large employers’ selection criteria in purchasing behavioral health benefits. J Behav Health Serv Res 2000; 27:334–338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Scanlon D, Chernew M: HEDIS measures and managed care enrollment. Med Care Res Rev 1999; 56:56–84Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hannan EL, Siu AL, Kumar D, Kilburn H Jr, Chassin MR: The decline in coronary artery bypass graft surgery mortality in New York State: the role of surgeon volume. JAMA 1995; 273:209–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Phibbs CS, Bronstein JM, Buxton E, Phibbs RH: The effects of patient volume and level of care at the hospital of birth on neonatal mortality. JAMA 1996; 276:1054–1059Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennber DE, Lucas FL: Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2117–2127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, Peterson DA: Treatment process and outcomes for managed care patients receiving new antidepressant prescriptions from psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:395–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Frank RG, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Some economics of mental health “carve-outs.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:933–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hermann RC, Dorwart RA, Hoover CW, Brody J: Variation in ECT use in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:869–875Link, Google Scholar

21. Rothman AA, Wagner EH: Chronic illness management: what is the role of primary care? Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:256–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar