Predictors of Premature Termination of Inpatient Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined predictors of premature dropout from a voluntary specialized inpatient treatment program for anorexia nervosa. METHOD: One hundred sixty-six consecutive patients with anorexia nervosa received an admission assessment that consisted of a diagnostic interview and psychometric measures of core eating pathology and associated psychopathology. Survival analysis was used to examine the rate, timing, and prediction of dropout. Predictors included a variety of clinical, demographic, and psychometric variables. RESULTS: Compared with program completers, program dropouts were more likely to have the binge eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa (65% versus 26%), had lower restraint scores, and reported more intense maturity fears and concerns about weight. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with the binge eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa are significantly less likely to complete inpatient treatment for the disorder.

The treatment of anorexia nervosa is a challenging process at all stages of illness and recovery. Given the well-established physical and psychological consequences of malnutrition and emaciation, it is generally agreed that nutritional rehabilitation and weight restoration must constitute the first step in the recovery process (1). This step usually involves a period of inpatient treatment. It has long been realized that patients with anorexia nervosa are ambivalent about treatment and often terminate treatment early. This pattern has held true despite a gradual shift from a more restrictive behavioral approach that often involved involuntary hospitalization toward a more flexible approach in which patients maintain a greater degree of control over the treatment process and there are fewer behavioral contingencies (2). Despite these changes, dropout and premature termination remain significant problems in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

The issue of premature termination of inpatient treatment is important because research has demonstrated that dropout is predictive of poorer posttreatment outcome (3–5) The identification of factors associated with premature discharge may help with the development of strategies to reduce rates of premature discharge and thus enhance overall rates of treatment success. To our knowledge, only two studies of this issue have been conducted (6, 7). The rates of dropout were 50% in the first study (6) and 33% in the second (7). In the first study, premature termination was associated with a later age at onset of anorexia nervosa, older age at admission, longer duration of illness, lower educational status, and lower socioeconomic status. In addition, patients who received behavior therapy were significantly more likely to drop out than those who received a nonspecific approach. In the second study, anorexia nervosa type (restricting versus binge eating/purging) was the only variable found to be predictive of dropout status; patients with the binge eating/purging type were more likely to drop out. In addition, patients with early termination had significantly more previous hospitalizations. The goal of the present study was to further examine predictors of premature discharge from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa.

Method

Patients and Recruitment

The study participants were recruited from the Inpatient Eating Disorders Unit at the Toronto General Hospital. This program has been described in detail elsewhere (8). It is an intensive group therapy program that is primarily directed at the normalization of eating and the restoration of body weight. There are few behavioral contingencies, and patients are limited in their privileges to the minimum extent possible. All patients are voluntary. Patients receive a limited amount of individual psychotherapy focused on specific issues (e.g., trauma, anxiety) and may also have family therapy as indicated.

Briefly, the program provides a mixture of nutritional rehabilitation, psychosocial therapy, and medical treatments. Caloric intake is increased if the desired amount of weight gain (1 kg/week) is not achieved. Patients begin to have weekend passes in the third week of treatment and transition to attending the program as day patients about halfway through their stay in the program. Patients may be discharged from the program by staff because of lack of progress (e.g., lack of weight gain, failure to stop purging), repeated violation of program norms (e.g., purging on the unit), or the development of serious comorbidity (e.g., psychosis). Patients may leave the program voluntarily at any time. Staff-initiated terminations typically involve a process involving several weeks of discussion with the patient about the difficulties he or she is encountering in the treatment setting and encouragement to make appropriate changes. All types of premature termination of treatment were included in the analysis for this study.

Participants in this study were consecutive first-admission patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa. For the purposes of this study, dropout was defined as discharge before achieving a body mass index (kg/m2) of 20.

Assessment Measures

At admission, all patients participated in an assessment that lasted approximately 90 minutes. A complete description of the study was provided, and written informed consent was obtained. Key eating disorder symptoms were assessed with the diagnostic items of the Eating Disorder Examination (9). Measures derived from this interview included the frequency of binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretic misuse, and intense exercise; degree of concern about shape and weight; and degree of dietary restriction. Other eating disorder features were measured by using the fourth edition of the self-report version of the Eating Disorder Examination (10) and the Eating Disorder Inventory (11) The Eating Disorder Examination produces four subscale scores: shape concern, weight concern, eating concern, and restraint. The Eating Disorder Inventory is composed of eight subscales: drive for thinness, bulimia, body dissatisfaction, ineffectiveness, perfectionism, interpersonal distrust, interoceptive awareness, and maturity fears. In addition, weight and height were measured in order to calculate body mass index.

Aspects of general psychopathology were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (12), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (13), and the Padua Inventory (14), which is a measure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Family functioning was measured with the Family Assessment Measure (15).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted by using SPSS Version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). The rate, timing, and prediction of dropout were examined by using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used to examine the equality of the survival distributions for categorical predictor variables (e.g., anorexia nervosa type), and the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to test the effect of continuous predictor variables (or covariates) on the hazard function (16). On the basis of a review of the literature on prognostic indicators in anorexia nervosa, the following variables were examined: age, marital status, employment status, and living situation (alone versus with others) at admission; age at onset of the eating disorder; duration of illness; previous use of specialized treatment for an eating disorder; body mass index at admission; maximum and minimum previous weight; anorexia nervosa type (binge eating/purging versus restricting); severity of eating disorder symptoms according to Eating Disorder Examination interview; and scores on the psychometric measures. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, each covariate was entered into the model individually to examine its effect on dropout. For psychometric measures with subscales, all subscales were entered into the equation in the same step. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all analyses. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study participants consisted of 166 patients (163 female and three male patients) who met the DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa. At admission, they had a mean age of 27.1 years (SD=9.0) and a mean body mass index of 14.9 (SD=1.8). The mean duration of illness was 6.7 years (SD=7.6). The average length of stay in treatment was 10.6 weeks (SD=6.3), and the mean weight gain in treatment was 10.1 kilograms (SD=6.9). Seventy-four percent (N=123) were single, 19% (N=31) were married or in common-law relationships, and 7% (N=12) were separated or divorced. Sixteen percent (N=26) lived alone before their hospital admission, and the remaining 84% (N=140) lived with parents/relatives, a partner/spouse, or friends. The majority of participants were unemployed (41%, N=68), 27% (N=45) were employed, and 32% (N=53) were students. Of the participants who provided information about ethnic background, 90.4% were Caucasian, 4.2% were Asian, 2.4% were East Indian, and the remaining 3.0% were Middle Eastern, African Canadian, or Hispanic. Ninety-one participants (55%) met the DSM-IV criteria for the binge eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa according to the Eating Disorder Examination interview; the remaining 75 patients (45%) met criteria for the restricting type of anorexia nervosa.

Rate of Attrition

Eighty-one patients (49%) completed the program and achieved a body mass index of 20, and 85 patients (51%) experienced a premature termination of treatment before achieving a body mass index of 20. The mean length of admission for program completers was 14.9 weeks (SD=4.8), compared with 6.2 weeks (SD=4.4) for patients with premature termination (t=12.26, df=164, p≤0.0001). The mean discharge body mass index for completers was 20.4 (SD=0.5), compared with 16.9 (SD=2.0) for patients with premature termination (t=15.94, df=164, p≤0.0001).

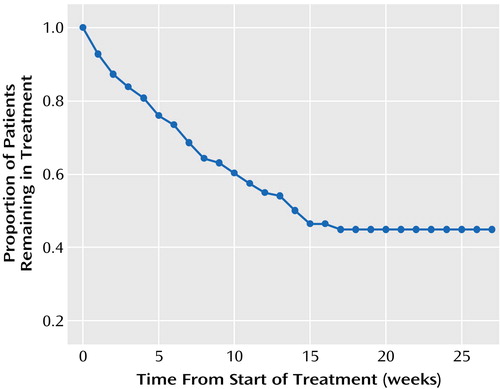

Time to Premature Termination of Treatment

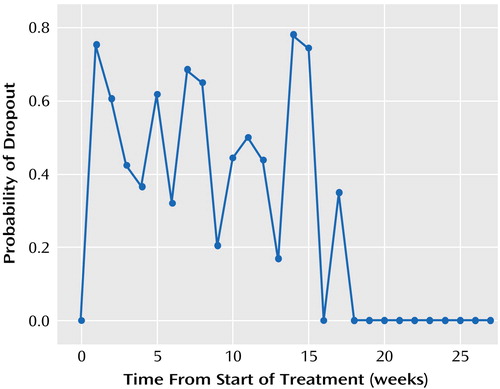

Figure 1 presents the survival curve for the entire study group of 166 patients. (Patients completing the program are censored at the time at which they complete the program.) The survival curve shows a gradual but steady decline to week 15 in the proportion of patients remaining in treatment. The median time to premature termination was 15.0 weeks (95% confidence interval [CI]=11.0–19.0). The hazard curve (Figure 2) showing probability of dropout for the entire study group (N=166) includes several peaks during the first 16 weeks, suggesting that the problem of premature termination of treatment is not confined to a particular week of participation. However, the highest peaks, which indicate the greatest probability for premature termination, occur at week 1 (probability=0.075) and again at weeks 14 (probability=0.078) and 15 (probability=0.074). There were no premature terminations after week 17.

Predictors of Premature Termination

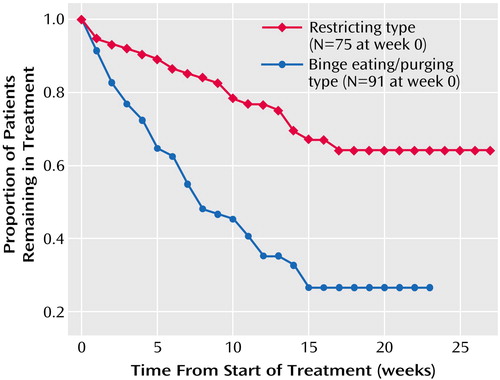

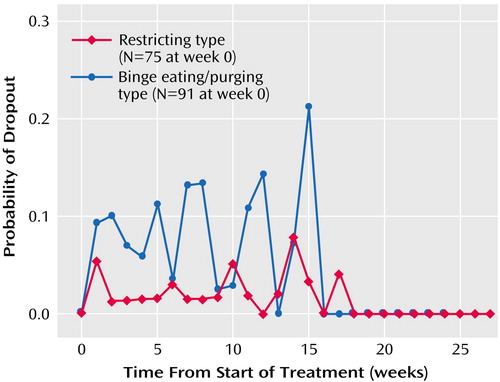

The first significant predictor of premature termination of treatment was anorexia nervosa type (Mantel-Cox χ2=24.32, df=1, p≤0.0001). Figure 3 shows the survival curves for patients with the binge eating/purging type and those with the restricting type of anorexia nervosa. (Patients completing the program are censored at the time at which they complete the program.) The overall survival rate was significantly lower for the patients with the binge eating/purging type (28%), compared with the patients with the restricting type (65%). Figure 4 shows the hazard profiles of the patients with the binge eating/purging type and those with the restricting type. Almost one-half (45%) of the patients with the binge eating/purging type experienced premature termination of treatment by week 7, compared to only 15% of the patients with the restricting type. In addition, the mean time to premature termination was significantly earlier for the patients with the binge eating/purging type (11.5 weeks, 95% CI=9.5–13.3), compared with the patients with the restricting type (20.6 weeks, 95% CI=18.4–22.8).

The second significant predictor of premature termination was body mass index at admission (hazard ratio=1.15, 95% CI=1.02–1.30, p<0.03). Patients with higher body mass indexes at admission were more likely to terminate treatment prematurely. Third, Beck Depression Inventory scores at admission were significantly associated with the probability of premature termination (hazard ratio=1.04, 95% CI=1.01–1.08, p<0.02), with higher levels of depression at baseline predicting lower survival rates.

As for the severity of eating disorder psychopathology, admission Eating Disorder Examination subscale scores for weight concern (hazard ratio=2.15, 95% CI=1.25–3.70, p=0.006) and restraint (hazard ratio=0.67, 95% CI=0.51–0.88, p=0.004) were significant predictors of premature termination of treatment. Higher weight concern scores and lower restraint scores were associated with a higher likelihood of premature termination. Finally, higher Eating Disorder Inventory maturity fears subscale scores (hazard ratio=1.05, 95% CI=1.00–1.11, p<0.04) significantly predicted premature termination.

On the basis of the hypothesis that some of these results may be accounted for by baseline differences between patients with the restricting type and patients with the binge eating/purging type, the predictor analyses were repeated with adjustment for anorexia nervosa type by forcing this variable into the Cox regression equation in the first step. After adjustment for type, only higher weight concern scores (hazard ratio=2.15, 95% CI=1.25–3.70, p=0.006), lower restraint scores (hazard ratio=0.67, 95% CI=0.51–0.88, p=0.004), and higher maturity fears scores (hazard ratio=1.07, 95% CI=1.02–1.12, p<0.02) were significantly associated with the probability of premature termination of treatment. Body mass index (p=0.37) and depression (p=0.09) no longer had a significant effect on the cumulative probability of premature termination.

Several other variables showed no significant effect on the cumulative probability of premature termination of treatment, including marital status (p=0.25) , employment status (p=0.40), living situation (p=0.71), age at onset (p=0.12), duration of illness (p=0.60), age at admission (p=0.23), maximum (p=0.55) and minimum (p=0.63) previous weight, previous use of specialized treatment for an eating disorder (p=0.43), and the frequency of binge eating (p=0.10) and purging (p=0.61) behavior in the 3 months before admission.

A post hoc decision was made to use a series of t tests to compare patients with the binge eating/purging type who had early premature termination of treatment (i.e., at 7 weeks of treatment or before) with those who had later premature termination (i.e., after 7 weeks). One result of this analysis approached significance: the patients with early premature termination had a monthly binge frequency of 42.8 episodes (SD=49.6), compared to 18.3 episodes (SD=21.7) for the patients with later premature termination (t=1.92, df=32, p=0.07).

Discussion

We identified a constellation of factors that predict premature dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. The observation that individuals with the binge eating/purging form of the illness have a significantly higher rate of dropout replicates earlier findings (4). In contrast to previous research (6), we did not find that older age at diagnosis and longer duration of illness were predictive of dropout from treatment. The findings that premature termination of treatment is associated with higher levels of weight concerns, greater maturity fears, and lower levels of restraint are new.

The large difference in the rate of premature termination of treatment between the patients with the restricting type and those with the binge eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa is striking. Not only is the absolute rate of premature termination higher in the latter group, but the premature terminations occur much earlier among the patients with the binge eating/purging type, with the majority of the terminations in this group occurring in the first 7 or 8 weeks of treatment. Our post hoc analysis comparing patients with the binge eating/purging type who had early versus late premature termination included only a small number of subjects, which possibly could have obscured relevant between-group differences. The nonsignificant finding of greater severity of illness, as evidenced by higher frequency of bingeing, in the patients with early termination suggests that further study of early versus late dropouts is warranted.

If further analysis identifies two groups of patients with the binge eating/purging type who had premature treatment termination—those with early and those with later premature termination—those with early premature termination might represent a group of patients who do not experience a rapid response to treatment. Wilson et al. (17) found that the majority of the response to cognitive behavior therapy for bingeing and purging occurs in the first 4 weeks of treatment. Individuals whose symptoms do not respond promptly might be more prone to leave treatment early. This group might benefit from additional interventions, such as focused cognitive behavior therapy, either before the initiation of intensive treatment or very early in the treatment process.

Our finding that lower restraint scores are associated with premature termination of treatment suggests that patients with premature termination have personality characteristics that include more impulsivity, leading them to be more prone to exit treatment early. Alternately, such individuals may perceive a greater degree of freedom in their eating and develop the idea that they no longer require treatment before their weight is fully restored. Patients with higher maturity fears and weight concerns would be more likely to exit treatment prematurely once the process of weight gain had become more prominent. Although some individuals might exit treatment at the first sign of weight gain, others might be able to tolerate the initial phase of treatment but decide to exit after passing some idiosyncratic threshold beyond which their concerns become too active.

Alternately, these individuals may be experiencing a more severe form of the illness and might perceive the treatment setting as overwhelming, which could lead them to develop a sense of hopelessness about recovery and an inability to continue in treatment. Further examination of the precise reasons for premature termination among patients with this psychometric profile might lead to changes in interventions that could be associated with improvements in outcome.

The treatment of the binge eating/purging type of anorexia nervosa requires further examination. Crafting alternate treatment interventions that achieve higher rates of treatment completion for this group is very important. To improve rates of treatment completion in this group, we will need to understand the nature of their decisions to terminate treatment more completely. One potentially promising approach is suggested by comparing the survival curves of the patients with the restricting type and those with the binge eating/purging type. It appears that the shapes of the two curves become very similar after 7 or 8 weeks, suggesting that at least some of the difference in the fate of the patients with the binge eating/purging type, compared to those with the restricting type, is related to specific factors experienced by patients with early premature termination. Continuing to examine the differences between patients with the binge eating/purging type who have early versus late premature termination of treatment may allow development of more effective interventions for this group of patients.

An additional area for further study is the potential differences between patients whose treatment ends because of a staff decision and those who choose to leave treatment of their own volition. Classifying patients with premature termination according to those categories can be a complex matter, as many decisions to terminate treatment are made collaboratively by the patient and the staff. In other cases, both the patient and the staff may be having similar thoughts about ending treatment early, but these views may develop at different speeds. Categorization of premature terminations requires further study before such comparisons can be made.

Received May 17, 2002; revisions received June 11 and Dec. 30, 2003; accepted Jan. 9, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Address reprint requests to Dr. Woodside, Department of Psychiatry, Toronto General Hospital, 200 Elizabeth St. 8EN-219, Toronto, Ont. M5G 2C4, Canada; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant MOP-44041 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors thank Kalam Sutandar-Pinnock for assistance with data collection and Shirley Sinclair for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Figure 1. Proportion of Patients With Anorexia Nervosa (N=166) Remaining in a Voluntary Inpatient Treatment Program Over a 27-Week Period From Start of Treatment

Figure 2. Probability of Dropout Over a 27-Week Period From Start of Treatment Among Patients With Anorexia Nervosa (N=166) in a Voluntary Inpatient Treatment Program

Figure 3. Proportion of Patients With the Restricting and Binge Eating/Purging Types of Anorexia Nervosa Remaining in a Voluntary Inpatient Treatment Program Over a 27-Week Period From Start of Treatment

Figure 4. Probability of Dropout Over a 27-Week Period From Start of Treatment Among Patients With the Restricting and Binge Eating/Purging Types of Anorexia Nervosa in a Voluntary Inpatient Treatment Program

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157(Jan suppl)Google Scholar

2. Touyz SW, Beumont PJ, Glaun D. Phillips T, Crowie I: A comparison of lenient and strict operant conditioning programs in refeeding patients with anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 517–520Google Scholar

3. Baran SA, Weltzin TE, Kaye WH: Low discharge weight and outcome in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1070–1072Link, Google Scholar

4. Halmi KA, Licinio-Paixao J: Outcome: hospital program for eating disorders, in 1989 Annual Meeting Syllabus and Proceedings Summary. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1989, p 314Google Scholar

5. Carter JC, Blackmore E, Sutandar-Pinnock K, Woodside DB: Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychol Med 2004; 34:671–679Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Vandereycken W, Pierloot R: Dropout during inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: a clinical study of 133 patients. Br J Med Psychol 1983; 56:145–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kahn C, Pike KM: In search of predictors of dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2001; 30:237–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Woodside DB, Sonnenberg S, Young K, Jonas D, Carter J, Kaplan AS, Martin R, Cowan R, Grigoriadis S: Inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa—the Toronto General Hospital Program, in Feeding Problems and Eating Disorders: Their Nature and Treatment. Edited by Cooper PJ, Stein A. New York, Harwood Academic (in press)Google Scholar

9. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination, 12th ed, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 317–360Google Scholar

10. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ: Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16:363–370Medline, Google Scholar

11. Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multi-dimensional Eating Disorder Inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983; 2:15–34Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Beck RW: Screening depressed patients in family practice: a rapid technique. Postgrad Med 1972; 52:81–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rosenberg M: Conceiving the Self. New York, Basic Books, 1970Google Scholar

14. Van Oppen P, Hoekstra RJ, Emmelkamp PMG: The structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behav Res Ther 1994; 33:15–23Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Skinner HA, Steinhauer PD, Sitarenios G: Family Assessment Measure (FAM) and process model of family functioning. J Fam Ther 2000; 22:190–210Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Luke DA: Charting the process of change: a primer on survival analysis. Am J Community Psychol 1993; 21:203–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Wilson GT, Fairburn CC, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Kraemer H: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: time course and mechanisms of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:267–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar