Genetic Boundaries of the Schizophrenia Spectrum: Evidence From the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Identification of the genetically related disorders in the putative schizophrenia spectrum is an unresolved problem. Data from the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia, which was designed to disentangle genetic and environmental factors influencing risk for schizophrenia, were used to examine clinical phenotypes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adopted-away offspring of mothers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. METHOD: Subjects were 190 adoptees at broadly defined genetic high risk who had biological mothers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, including a subgroup of 137 adoptees at narrowly defined high risk whose mothers had DSM-III-R schizophrenia. These high-risk groups, followed to a median age of 44 years, were compared diagnostically with 192 low-risk adoptees whose biological mothers had either a non-schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis or no lifetime psychiatric diagnosis. RESULTS: In adoptees whose mothers had schizophrenia, the mean lifetime, age-corrected morbid risk for narrowly defined schizophrenia was 5.34% (SE=1.97%), compared to 1.74% (SE=1.00%) for low-risk adoptees, a marginally nonsignificant difference. In adoptees whose mothers had schizophrenia spectrum disorders, the mean age-corrected morbid risk for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder was 22.46% (SE=3.56%), compared with 4.36% (SE=1.51%) for low-risk adoptees, a significant difference. Within the comprehensive array of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, schizotypal personality disorder was found significantly more often in high-risk than in low-risk adoptees. The frequency of the group of nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses collectively differentiated high-risk and low-risk adoptees, but the frequencies of the separate disorders within this category did not. The two groups were not differentiated by the prevalence of paranoid personality disorder and of affective disorders with psychotic features. CONCLUSIONS: In adopted-away offspring of mothers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, the genetic liability for schizophrenia-related illness (with the rearing contributions of the biological mothers disentangled) is broadly dispersed. Genetically oriented studies of schizophrenia-related disorders and studies of genotype-environment interaction should consider not only narrowly defined, typical schizophrenia but also schizotypal and schizoid personality disorders and nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses.

The question of the boundaries of schizophrenia has been controversial ever since 1911, when Eugen Bleuler (1) observed that certain “fundamental” features of Kraepelin’s dementia praecox (2) could be found in “latent” form. However, after Kety et al. (3) in 1968 introduced the term “schizophrenia spectrum” to refer to all disorders that are “to some extent genetically transmitted” with schizophrenia, the identification of which disorders should be under this genetic umbrella became a focus of investigation.

Efforts to develop operational definitions of latent schizophrenia led to development of the criteria for DSM-III schizotypal personality disorder. In DSM-III-R, cluster A, or the “odd cluster,” of presumptively schizophrenia-related, nonpsychotic personality disorders included schizotypal (4), schizoid (5), and paranoid (6, 7) personality disorders. Avoidant personality disorder (8, 9) has been proposed as an addition to this group.

In addition, many studies have proposed or rejected schizophrenia spectrum status for at least six psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia—schizoaffective disorder (6), schizophreniform disorder (10), delusional disorder (6, 11, 12), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (6, 13), and bipolar and depressive disorders with psychotic features (10, 14). However, identification of the specific nonpsychotic and psychotic disorders that belong within the genetic boundary of the “schizophrenic spectrum” is acknowledged in DSM-IV-TR to be an “unresolved problem.” As a starting point for this report, we designated the following array of psychoses and personality disorders as the putative broad spectrum that we would evaluate: DSM-III-R schizophrenia; schizotypal, schizoid, paranoid, and avoidant personality disorders; schizoaffective, schizophreniform, and delusional disorders; bipolar disorder with psychosis; depressive disorder with psychosis; and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. The landmark Danish adoption studies of Kety et al. (3) that initiated the study of the schizophrenia spectrum used two primary designs for identifying the family members designated as being at genetic risk. The study by Kety et al. (3) started with proband adoptees and primarily targeted their siblings and half-siblings. Kendler and colleagues (5, 15) redetermined the diagnoses of these subjects using the DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia and a narrow spectrum of schizoaffective disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, and paranoid personality disorder.

A companion study in Denmark by Rosenthal et al. (16) that focused on adopted-away offspring was most similar in design to the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia, which provided the data used in the analyses reported here. Lowing et al. (17) redetermined the diagnoses of 39 index adoptees and comparison subjects from the Rosenthal study using DSM-III criteria but retained the more global, nonoperational DSM-II criteria for the proband parents who gave offspring up for adoption.

Using the DSM-III-R criteria, we evaluated a much larger group of proband biological mothers and their adopted-away offspring. In addition, the adoptees were independently reevaluated in an 18-year follow-up. In recent publications (18, 19), we reported data on the initial direct assessment of communication patterns of the adoptive rearing parents, providing an opportunity to evaluate genotype-environment interaction in the schizophrenia spectrum. This report focuses on the genetic side of the coin. The goal of this analysis was to suggest genetically informative clinical phenotypes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders that may deserve consideration in current gene-mapping approaches.

Method

Subject Selection

The full details of subject selection have been reported previously (20). In summary, hospital records for all 19,447 women admitted to Finnish psychiatric hospitals from January 1, 1960, through 1979 were reviewed to identify those who had at least once received a diagnosis of a schizophrenic or paranoid psychosis. This list was checked manually through every census and parish register in the country to find index mothers who had given one or more offspring up for adoption. Their index offspring and their adoptive families were demographically matched with adoptive families and offspring who had been given up for adoption by diagnostically unscreened biological mothers who had a full array of psychiatric and physical illnesses, as found in the community.

Diagnostic Procedures for Biological Mothers

Later, research diagnoses made by using the DSM-III-R criteria were obtained through review of initial and subsequent hospital and clinic records and personal research interviews carried out with all available index and comparison biological mothers and fathers (21, 22). The diagnosticians who provided the research diagnoses for the mothers were blind to the status of the adopted-away offspring.

In addition, Finnish national computerized registers were searched for all subjects in the study. A register giving reasons for death was searched through November 2000, and the hospital discharge register for all public and private inpatients was searched through December 31, 2000. Other registers were searched through October 1994 for records of diagnoses that justified disability pension; information on sick leave prescribed by a doctor; records of free medication prescribed for certain illnesses, including psychoses; and information about criminality.

Adoptee Diagnostic Procedures

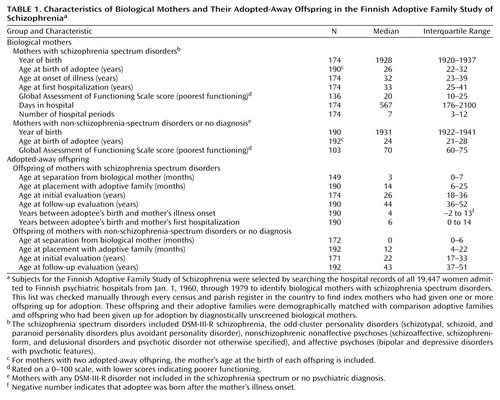

Initial and follow-up evaluations of the adoptees were carried out in two waves with a median interval of 18 years (Table 1). Whenever possible, these evaluations included personal interviews, as well as a review of hospital records and registers and interviews with family members and other informants. The follow-up interviews were conducted by research psychiatrists who were blind to the results of all prior assessments of the adoptees and of both the biological and the adoptive relatives. The follow-up interview schedules included an expanded lifetime version of the Present State Examination (23), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (24), and the Structured Interview for Schizotypy (25). Personal interviews were carried out either initially or at follow-up, or both, with 346 adoptees (176 high-risk and 170 low-risk adoptees, 90.6% of all adoptees). An updated register search for data on all subjects took place at the end of 2000.

Risk Reassignments of Adoptees

The original selection of proband biological mothers was based on hospital records in which the global ICD-8 and ICD-9 criteria for schizophrenia (code 295 in ICD-8 and ICD-9 and DSM-II) and paranoid psychosis (code 297) were used. The “index” and “comparison” selection process for the adoptees had been truly epidemiological, but their diagnoses had been made by using nonoperational criteria (20). In contrast, we report here final research diagnoses made by using DSM-III-R, updated through December 2000, for biological mothers and for both the high-risk and low-risk adoptees. The biological mothers of the low-risk adoptees included women who may have had a non-schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis and in that respect are not “supernormal control subjects” (26).

Here we focus on specific diagnostic phenotypes of the biological mothers and assess the associated genetic risk in the adoptees. Therefore, we reassigned adoptees so that all high-risk adoptees had biological mothers with confirmed research diagnoses within the broad putative schizophrenia spectrum and all low-risk adoptees had biological mothers with no psychiatric diagnosis or with a non-schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis. The high-risk adoptees included those at narrowly defined high risk (whose mothers had DSM-III-R schizophrenia) and those at broadly defined high risk (whose mothers had any lifetime diagnosis in the broad putative schizophrenia spectrum).

First we added 16 second-born offspring of the 170 index mothers and two second-born offspring of the 201 comparison mothers. Changes based on later personal interviews and other information were as follows: 1) Three biological mothers in the original index sample were found on later research to have nonspectrum diagnoses; one had nonpsychotic depression, one had alcoholic hallucinosis with antisocial personality disorder, and one had borderline personality disorder (this mother gave two offspring up for adoption). These four adoptees were assigned to the low-risk group. 2) Fourteen comparison mothers were found to have research diagnoses in the putative broad schizophrenia spectrum, and their 15 offspring were assigned to the genetic high-risk group. After the initial selection, two of these mothers developed schizophrenic symptoms, one developed major depression, and one developed bipolar disorder, both of the latter with psychotic features. With research evaluation, the other 10 comparison mothers were found to have personality disorders within the putative spectrum: three with schizotypal personality disorder (one with two offspring), one with schizoid personality disorder, one with paranoid personality disorder, and five with avoidant personality disorder.

In an effort to ensure diagnostic consistency, we eliminated seven adoptees who originally were in the index epidemiological group but who had no registered psychiatric treatment. We can be confident that they did not have a psychotic disorder, but they could have had an untreated schizophrenia spectrum personality disorder.

In summary, after diagnostic reassignment, the study groups consisted of 190 adoptees at “broadly defined” genetic high risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders (the offspring of 174 mothers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders), which included a subsample of 137 adoptees at “narrowly defined” high risk (the offspring of 125 mothers with schizophrenia), and 192 adoptees at genetic low risk (the offspring of 190 mothers with a non-schizophrenia-spectrum disorder or no psychiatric diagnosis).

Sample Demographic/Clinical Characteristics

At register follow-up in December 2000, the median ages of the study groups were 44 years for the high-risk adoptees and 43 years for the low-risk adoptees (Table 1). By follow-up, most of the adoptees had passed through the age of primary risk for onset of schizophrenia. Of the high-risk adoptees, 92 were male and 98 female. Of the low-risk adoptees, 90 were male and 102 were female.

Clinical data about the biological mothers were obtained primarily at three points in time: 1) from hospital records dating from the median year of 1961 for mothers at a median age of 33 years; 2) from personal interviews, most of which were carried out from 1980 to 1983; and 3) from comprehensive register and record follow-ups that were concluded in 2000. During their lifetimes, the biological mothers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders had experienced severe illness with multiple long hospitalizations. It is especially noteworthy that the high-risk adoptees were born a median of 4 years before the onset of the mother’s illness and a median of 6 years before the mother’s first hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

Cross-tabulated categories of diagnostic prevalence were collapsed to dichotomies, and initial analyses were done on the basis of two-by-two tables calculating relative risk with confidence intervals and p values from one-tailed chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The Kaplan-Meier method, as operationalized in the survival analysis procedure of the SPSS for Windows software (27), was used to obtain curves for the estimated cumulative proportions of high-risk versus low-risk adoptees by age at onset of schizophrenia and all psychoses. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to yield the estimates of age-corrected lifetime morbid risk for psychoses (28). The statistical significance of the differences between survival curves for the high-risk group and those for the low-risk group was determined by using the log-rank test.

Results

Offspring of Mothers With Schizophrenia

Adoptees with schizophrenia

First, we evaluated whether the liability for schizophrenia was transmitted to adoptees in the form of narrowly defined “typical” schizophrenia. This stringent test of liability began by assessing the prevalence of schizophrenia among the 137 adoptees whose biological mothers had schizophrenia, compared to the prevalence among the 192 low-risk adoptees. As Table 2 shows, seven (5.1%) high-risk adoptees had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, compared to three (1.6%) low-risk adoptees. (The diagnoses of schizophrenia for the three low-risk adoptees were independently confirmed by two diagnosticians, and their biological mothers were personally and independently interviewed.) The relative risk of a diagnosis of schizophrenia for the high-risk adoptees was 3.27 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.86–12.42, p=0.07, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 3).

Similarly, in the Kaplan-Meier procedure with age at onset entered for schizophrenia, the difference in the lifetime, age-corrected morbid risk for schizophrenia between the high-risk adoptees and the low-risk adoptees approached significance (p=0.06, log-rank test) (Table 4).

Adoptees with schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Table 2 shows that the liability was by no means limited to schizophrenia. Collectively, the prevalence for the odd-cluster personality disorder diagnoses, with avoidant personality disorder included, significantly differentiated the narrowly defined high-risk adoptees from the low-risk adoptees. Eleven of the 137 narrowly defined high-risk adoptees, compared to four of 192 low-risk adoptees, had an odd-cluster personality disorder (relative risk=3.85, 95% CI=1.25–11.85, χ2=6.50, df=1, p=0.01) (Table 3).

The most frequent specific diagnosis, next to schizophrenia itself, was schizotypal personality disorder, found in four (2.9%) of the 137 high-risk adoptees and in none of the low-risk adoptees (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test). Indeed, schizotypal personality disorder was the only disorder that was found significantly more often in the high-risk adoptees than in low-risk adoptees.

The nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses were less prevalent than the personality disorders, with none of them standing out as distinctive. Collectively these disorders occurred in three of the 137 high-risk adoptees versus none of the 192 low-risk adoptees (p=0.07, Fisher’s exact test). The mean age-corrected morbid risk was 3.40% (SD=2.12%) for the adoptees at narrowly defined high risk and 0.0% for the low-risk adoptees (p=0.04, log-rank test).

In contrast, the differentiation of adoptees with affective psychoses was nonsignificant: the prevalence was three among the 137 narrowly defined high-risk adoptees and one among the 192 low-risk adoptees (relative risk=4.20, 95% CI=0.44–39.99, p=0.20, Fisher’s exact test). The mean difference in morbid risk was 3.98% (SD=2.64%) for the high-risk adoptees versus 0.55% for the low-risk adoptees (SE=0.54%) (p=0.18, log-rank test).

Among all of the offspring of the mothers with schizophrenia, we found a total of 24 adoptees with disorders representing the broad group of nine schizophrenia spectrum disorders, including seven with schizophrenia. In contrast to the marginal differentiation of high-risk and low-risk adoptees with schizophrenia, the differentiation of adoptees with any broad schizophrenia spectrum disorder was highly significant: 24 (17.5%) of 137 versus eight (4.2%) of 192 (relative risk=4.20, 95% CI=1.95–9.08, χ2=16.23, df=1, p<0.001).

Similarly, the mean age-corrected morbid risk for broad spectrum diagnoses for the adoptees with narrowly defined high risk was 20.28% (SE=4.10%) versus 4.36% (SE=1.51%) for low-risk adoptees (p<0.001, log-rank test) (age at onset for personality disorders was set at 18 years).

Offspring of Mothers With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Adoptees with schizophrenia

We consider here the total group of 190 adoptees with biological mothers with disorders in the putative broad schizophrenia spectrum, including 53 adoptees whose mothers had a spectrum disorder other than schizophrenia. The prevalence of typical schizophrenia in this larger group of high-risk adoptees increased to 12 (6.3%) of 190 versus three (1.6%) of 192 low-risk adoptees, a significant difference (χ2=5.72, df=1, p=0.02). Also, the differentiation in morbid risk was significant (Table 4).

Adoptees with schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Within the full group of 190 adoptees whose mothers had broadly defined schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 15 (7.9%) were given an odd-cluster personality diagnosis. The differentiation from low-risk adoptees was highly significant (χ2=6.82, df=1, p=0.009) (Table 3). The two disorders with significantly different prevalences in the full group of 190 adoptees, compared with the low-risk adoptees, were schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder (Table 3). Among the personality disorders, schizoid personality disorder, the second best differentiating disorder, was found in five high-risk adoptees, compared with one low-risk adoptee (relative risk=5.08, 95% CI=0.60–42.85, p=0.11, Fisher’s exact test). However, the two groups were not differentiated by the prevalence of paranoid personality disorder, which was found in one adoptee in the high-risk group and one in the low-risk group. Avoidant personality disorder was slightly but nonsignificantly more prevalent among the broadly defined high-risk adoptees (four of 190 versus two of 192).

Although none of the nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses considered separately were prevalent enough to differentiate high-risk from low-risk adoptees, collectively these disorders, which were found in five high-risk adoptees and no low-risk adoptees, differentiated the two groups (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test). With schizophrenia excluded, the mean age-corrected morbid risk for these disorders in the high-risk group was 4.23% (SE=1.97%) versus 0.0% for the low-risk group (p=0.02, log-rank test).

The prevalence of affective psychoses among the adoptees at broadly defined high-risk was not significantly different from the prevalence among the low-risk adoptees (p=0.11, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 3). The difference between groups in morbid risk for affective psychoses was not significant (p=0.10, log-rank test) (Table 4). For bipolar disorder alone, the differentiation in morbid risk between groups was somewhat better (p=0.07, log-rank test).

Most broadly, when all offspring with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder whose biological mothers had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder were considered as a group, the differentiation of high-risk and low-risk adoptees was most highly significant: 37 (19.5%) of 190 high-risk adoptees had a broadly defined schizophrenia spectrum disorder versus eight (4.2%) of 192 low-risk adoptees (relative risk=4.67, 95% CI=2.24–9.77, χ2=21.53, df=1, p<0.001). The mean age-corrected morbid risk was 22.46% (SE=3.56%) for the high-risk group and 4.36% (SE=1.51) for the low-risk group (p<0.001, log-rank test).

General Liability to Psychiatric Disorder

Finally, we considered the possibility that the liability to schizophrenia transmitted in families is a general liability to psychiatric disorders. This possibility was tested, first, by evaluating whether the high-risk adoptees had an increased prevalence and relative risk of DSM-III-R clusters B and C personality disorders (not including avoidant personality disorder). The difference in prevalence between the high-risk and low-risk adoptees was not statistically significant: 33 of 190 high-risk adoptees (17.4%, SE=3.2%) versus 22 of 192 low-risk adoptees (11.5%, SE=2.3%) (relative risk=1.53, 95% CI=0.90–2.61, χ2=2.44, df=1, p=0.12). None of the major non-schizophrenia-spectrum axis I disorders (nonpsychotic mood disorder, anxiety disorders, and alcohol abuse) separately or collectively differentiated the adoptees with either narrowly defined or broadly defined high risk from the low-risk adoptees (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study of genetic liability for schizophrenia-related disorders, we evaluated adoptees for the presence of schizophrenia and 10 other psychiatric disorders as part of a putative schizophrenia spectrum. (Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified was found in the biological mothers at high risk but not in the adoptees.) This group of disorders is a wider array than has been examined in previous family or adoption studies of schizophrenia-related disorders. Schizotypal personality disorder clearly stood out from the other odd-cluster personality disorders as more prevalent among adoptees at genetic high risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders than among adoptees at low risk. Paranoid personality disorder and major depression with psychotic features were the least closely linked to the rest of the putative schizophrenia spectrum. The difference in prevalence between the high-risk and low-risk groups for schizoid personality disorder was between that for schizotypal personality disorder and paranoid personality disorder. The difference in prevalence of avoidant personality disorder was also marginal, as it was found in both the low-risk and high-risk groups. The nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses aggregated significantly, but none of them stood out in the way that schizotypal personality disorder did. Nor did the nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses differentiate high-risk and low-risk adoptees as clearly as did the odd cluster of personality disorders as a group.

The status of the affective psychoses in relation to the schizophrenia spectrum is controversial, although they are usually excluded from the schizophrenia spectrum. However, Kendler et al. (29) suggested they should be placed at the outer margin of the spectrum. By including them in the putative spectrum, we explored this possibility. We found that neither bipolar disorder with psychotic features nor depressive disorder with psychotic features significantly differentiated high-risk from low-risk adoptees, although the p value was closer to the range of significance for bipolar disorder (p=0.07).

The most widely cited adoption study of schizophrenia, the Danish study headed by Kety (3), was comparable to the Finnish study in that both studies obtained comprehensive national samples by using epidemiological records and registers, not sampling “by convenience.” However, the Danish and Finnish studies differed in one critical respect: in the Danish study, the targeted relatives of the proband adoptees were their siblings, half-siblings, and parents, but none of the relatives were offspring; in the Finnish study, all of the targeted biological relatives were offspring.

Although parents, siblings, and offspring are all first-degree relatives of probands, the common practice of aggregating data for these relationships is not justifiable. Gottesman’s summary analysis of nonadoption family studies found that the risk for developing schizophrenia was 13% in offspring of probands with schizophrenia, compared to 9% in siblings and 6% in parents (30). However, nearly all of these studies were carried out before the use of the DSM-III criteria, issued in 1980, or the DSM-III-R criteria, issued in 1987, and it is uncertain whether use of the newer criteria would modify these figures. Differences in risk between studies may have been caused by differences in subjects’ rate of reproductive infertility and age at onset of schizophrenia and related disorders.

To our knowledge, only two prior studies have examined the risk of developing schizophrenia in offspring reared by biological parents with schizophrenia (31–33). These studies found morbid risks for schizophrenia of 16.2% (31) and 11.1% (32, 33) in the offspring, approximating the 13% reported by Gottesman from earlier nonadoption studies (30). Thus, the morbid risk for schizophrenia in the Finnish adoptees whose biological mothers had schizophrenia was much lower (5.34%). Can this difference be attributed to protective rearing by the adoptive parents? We shall examine this issue more fully in a forthcoming article on the interaction of genetics and family rearing environment.

The Finnish study had a substantial number (N=137) of adoptees whose mothers had schizophrenia, permitting us to look for a full array of broad schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the offspring. However, a limitation of the study was the relatively small number of adoptees whose biological mothers had schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses other than typical schizophrenia. This sampling imbalance resulted from the initial selection of mothers with hospital diagnoses of schizophrenia or paranoid psychosis. It was surprising to find that of the 53 adoptees at broadly defined genetic risk, 24.5% met the criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis across seven categories, including five adoptees with typical schizophrenia.

Overall, these findings suggest a low-level multifactorial liability, dispersed across the broad range of disorders found in the offspring of mothers with typical schizophrenia, but also found collectively in the smaller sample of offspring of mothers with other disorders in the broad schizophrenia spectrum. The traditional categorical approach to diagnosis used in this study should be supplemented by further research using dimensional, latent class (34), and “domain” (35) approaches to the classification of clinical phenotypes. The findings reported here strengthen the case for going beyond a narrow definition of schizophrenia both in refined research on the genetics of phenotypes and in genetic mapping approaches (36, 37).

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 19, 2001; revision received March 11, 2003; accepted March 19, 2003. From the Departments of Psychiatry, University of Oulu; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Tienari, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oulu, PL 5000, 90014 Oulun Yliopisto, Oulu, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH 39633 (Dr. Wynne), the Scottish Rite Schizophrenia Research Program (Dr. Wynne), and the Finnish Academy (Dr. Tienari, Dr. Moring). The authors thank Kenneth Kendler, M.D., for consultative assistance and Mikko Naarala, M.D., Jukka Pohjola, M.D., Merja Kaleva, M.D., Asko Niemelä, M.D., Sami Räsänen, M.D., Hannu Säävälä, M.D., Tarja Lämsä, M.D., Kalevi Hassinen, M.D., Outi Saarento, M.D., Markku Seitamaa, M.A., and Kristiina Kurki-Suonio, M.D., for their participation in interviewing and other aspects of the study.

1. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (1911). Translated by Zinkin J. New York, International Universities Press, 1950Google Scholar

2. Kraepelin E: Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. Leipzig, Barth, 1903Google Scholar

3. Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH, Schulsinger F: The types and prevalence of mental illness in the biological and adoptive families of adopted schizophrenics. J Psychiatr Res 1968; 6(suppl 1):345–362Google Scholar

4. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M: Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:17–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM: An independent analysis of the Danish Adoption Study of Schizophrenia, VI: the relationship between psychiatric disorders as defined by DSM-III in the relatives and adoptees. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:555–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM, Tsuang MT: Psychiatric illness in first-degree relatives of schizophrenic and surgical control patients: a family study using DSM-III criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:770–779Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM: Genetic relationship between paranoid personality disorder and the “schizophrenic spectrum” disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:1185–1186Link, Google Scholar

8. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, O’Hare A, Spellman M, Walsh D: The Roscommon Family Study, III: schizophrenia-related personality disorders in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:781–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Asarnow RF, Nuechterlein KH, Fogelson D, Subotnik KL, Payne DA, Russell AT, Asamen J, Kuppinger H, Kendler KS: Schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorders in the first-degree relatives of children with schizophrenia: the UCLA Family Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:581–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Maier W, Falkai P, Wagner M: Schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a review, in Schizophrenia. Edited by Maj M, Sartorius N. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999, pp 311–371Google Scholar

11. Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM, Strauss JS: An independent analysis of the Copenhagen sample of the Danish Adoption Study of Schizophrenia, III: the relationship between paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:985–987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kendler KS, Hays P: Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia: a family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:547–551Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Prescott CA, Gottesman II: Genetically mediated vulnerability to schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin of North Am 1993; 16:245–267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kendler KS: Schizophrenia: genetics, in Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, pp 1147–1158Google Scholar

15. Kendler KS, Gruenberg A, Kinney D: Independent diagnoses of adoptees and relatives as defined by DSM-III in the provincial and national samples of the Danish Adoption Study of Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:456–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosenthal D, Wender PH, Kety SS, Schulsinger F, Welner J, Ostergaard L: Schizophrenics’ offspring reared in adoptive homes, in The Transmission of Schizophrenia. Edited by Rosenthal D, Kety SS. London, Pergamon Press, 1968, pp 377–391Google Scholar

17. Lowing PA, Mirsky AF, Pereira R: The inheritance of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a reanalysis of the Danish adoptee study data. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1167–1171Link, Google Scholar

18. Wahlberg KE, Wynne LC, Oja H, Keskitalo P, Pykäläinen L, Lahti I, Moring J, Naarala M, Sorri A, Seitamaa M, Läksy K, Kolassa J, Tienari P: Gene-environment interaction in vulnerability to schizophrenia: findings from the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:355–362Link, Google Scholar

19. Wahlberg KE, Wynne LC, Oja H, Keskitalo P, Anias-Tanner H, Koistinen P, Tarvainen T, Hakko H, Lahti I, Moring J, Naarala M, Sorri A, Tienari P: Thought disorder index of Finnish adoptees and communication deviance of their adoptive parents. Psychol Med 2000; 30:127–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Tienari P, Wynne LC, Moring J, Läksy K, Nieminen P, Sorri A, Lahti I, Wahlberg KE, Naarala M, Kurki-Suonio K, Saarento O, Koistinen P, Tarvainen T, Hakko H, Miettunen J: Finnish Adoptive Family Study: sample selection and adoptee DSM-III-R diagnoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:433–443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Tienari P, Lahti I, Sorri A, Naarala M, Wahlberg KE, Ronkko T, Moring J, Wynne LC: The Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia: possible joint effects of genetic vulnerability and family interactions, in Understanding Major Mental Disorder: The Contributions of Family Interaction Research. Edited by Hahlweg K, Goldstein MJ. New York, Family Process Press, 1987, pp 33–54Google Scholar

22. Tienari P, Sorri A, Lahti I, Naarala M, Wahlberg KE, Moring J, Pohjola J, Wynne LC: Genetic and psychosocial factors in schizophrenia: the Finnish Adoptive Family Study. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:477–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N: The Measurement and Classification of Psychiatric Symptoms: An Instructional Manual for the PSE and CATEGO Programs. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1974Google Scholar

24. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1986Google Scholar

25. Kendler KS, Lieberman JA, Walsh D: The Structured Interview for Schizotypy (SIS): a preliminary report. Schizophr Bull 1989; 15:559–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kendler KS: The super-normal control group in psychiatric genetics: possible artifactual evidence for coaggregation. Psychiatr Genet 1990; 1:45–53Google Scholar

27. SPSS Advanced Models 10.0. Chicago, SPSS, 1999Google Scholar

28. Parmar MK, Machin D: Survival Analysis: A Practical Approach. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1996Google Scholar

29. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, Spellman M, O’Hare A, Walsh D: The Roscommon Family Study, II: the risk of nonschizophrenic nonaffective psychoses in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:645–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Gottesman II: Schizophrenia Genesis. New York, WH Freeman, 1991Google Scholar

31. Parnas J, Cannon T, Jacobsen B, Schulsinger H, Schulsinger F, Mednick S: Lifetime DSM-III-R diagnostic outcomes in the offspring of schizophrenic mothers: results from the Copenhagen High-Risk Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:707–714Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Squires-Wheeler E, Adamo U, Basset A, Cornblatt B, Kestenbaum C, Rock D, Roberts S, Gottesman I: The New York High-Risk Project: psychoses and cluster A personality disorders in offspring of schizophrenic parents at 23 years of follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:857–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Adamo U, Rock D, Roberts S, Basset A, Squires-Wheeler E, Cornblatt B, Endicott J, Papec S, Gottesman I: The New York High-Risk Project: prevalence and comorbidity of axis I disorders in offspring of schizophrenic patients at 25-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1096–1102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Walsh D: The structure of psychosis: latent class analysis of probands from the Roscommon Family Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:492–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AMI: Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:578–583Link, Google Scholar

36. Rutter M: Psychiatric genetics: research challenges and pathways forward. Am J Med Genet 1994; 54:185–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kendler KS, O’Neill FA, Burke J, Murphy B, Duke F, Straub RE, Shinkwin R, Ni Nuallain M, MacLean CJ, Walsh D: Irish study on high-density schizophrenia families: field methods and power to detect linkage. Am J Med Genet 1996; 67:179–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar