The Effectiveness of Psychodynamic Therapy and Cognitive Behavior Therapy in the Treatment of Personality Disorders: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors conducted a meta-analysis to address the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders. METHOD: Studies of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy that were published between 1974 and 2001 were collected. Only studies that 1) used standardized methods to diagnose personality disorders, 2) applied reliable and valid instruments for the assessment of outcome, and 3) reported data that allowed calculation of within-group effect sizes or assessment of personality disorder recovery rates were included. Fourteen studies of psychodynamic therapy and 11 studies of cognitive behavior therapy were included. RESULTS: Psychodynamic therapy yielded a large overall effect size (1.46), with effect sizes of 1.08 found for self-report measures and 1.79 for observer-rated measures. For cognitive behavior therapy, the corresponding values were 1.00, 1.20, and 0.87. For more specific measures of personality disorder pathology, a large overall effect size (1.56) was seen for psychodynamic therapy. Two cognitive behavior therapy studies reported significant effects for more specific measures of personality disorder pathology. For psychodynamic therapy, the effect sizes indicate long-term rather than short-term change in personality disorders. CONCLUSIONS: There is evidence that both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy are effective treatments of personality disorders. Since the number of studies that could be included in this meta-analysis was limited, the conclusions that can be drawn are only preliminary. Further studies are necessary that examine specific forms of psychotherapy for specific types of personality disorders and that use measures of core psychopathology. Both longer treatments and follow-up studies should be included.

Personality disorders are characterized by long-standing and pervasive dysfunctional patterns of cognition, affectivity, interpersonal relations, and impulse control that cause considerable personal distress (DSM-IV) (1, 2). In subjects with personality disorders, psychosocial impairment and the use of mental health resources are high (3–5). The prevalence of patients with personality disorders in inpatient and outpatient psychiatric populations is high (e.g., the prevalence of borderline personality disorder is estimated to be between 15% and 25% [6]). However, there is a considerable lack of empirical research on treatment of personality disorders with psychotherapy, with only a few randomized controlled studies (7). To address concerns about costs of mental health services, empirical data about the efficacy of psychotherapy in the treatment of personality disorders are needed. There is evidence that psychotherapy in general is an effective treatment for personality disorders (7, 8), but existing studies indicate that outcome may differ for different forms of psychotherapy (9, 10) and different personality disorders (11, 12).

For this reason, this review examined the effects of the two most frequently applied forms of psychotherapy in the treatment of personality disorders, psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Our review addressed the following questions:

| • | What is the evidence of improvement in symptoms, social functioning, or core psychopathology after psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy? | ||||

| • | Is there evidence of improvement in specific types of personality disorders after psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy? | ||||

| • | Do individuals with personality disorders recover after psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy? | ||||

| • | Are there differences between self-report and observational measures? | ||||

| • | Is there a correlation between outcome and duration of treatment? | ||||

| • | What other factors are connected with outcome (gender, inpatient versus outpatient status, use of therapy manuals, experience of therapists)? | ||||

Since only a few randomized controlled treatment studies exist, we included both controlled and naturalistic treatment studies.

Method

We collected studies of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy that were published between 1974 and 2001 by carrying out a computerized search using MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Current Contents. We included studies that 1) examined specific and explicitly described forms of psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy, 2) used standardized methods for diagnosing personality disorders, 3) used reliable and valid instruments for the assessment of outcome, and 4) reported data that allowed calculation of within-group effect sizes or assessment of personality disorder recovery rates.

In order to assess long-term change after psychotherapy, we selected the longest posttreatment follow-up for evaluation.

Twenty-two studies met these inclusion criteria (9, 10, 12–31). Three of these studies examined the effects of both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy (9, 10, 13). Since there were only three randomized controlled studies for psychodynamic therapy and five for cognitive behavior therapy, we calculated within-group effect sizes for all studies by using Cohen’s d (32). For each measure, we subtracted the posttreatment mean from the pretreatment mean and divided the difference by the pretreatment standard deviation of the measure. If there was more than one patient group, we calculated a pooled baseline standard deviation, as suggested by Rosenthal (33). If necessary, signs were reversed so that a positive effect size always indicated improvement. Whenever multiple measures were applied in a study, we assessed the effect size for each measure separately and calculated the mean effect size in order to assess the overall outcome of the study. We computed both unweighted effect sizes and effect sizes weighted by the sample size in order to yield unbiased estimators of effect sizes (34). Since Cohen’s d gives the amount of change in units of the standard deviation, a standardization of different scalar values of outcome measures is achieved. However, different outcome measures may be more sensitive to change than others (e.g., measures of depression versus measures of personality traits). Thus, the effect sizes of different outcome measures may not be comparable. For this reason, it may be useful to assess effect sizes for certain (classes of) outcome measures separately (33). Therefore, we not only computed an overall effect size but also assessed effect sizes separately for measures that were more specific to the core pathology of personality disorders. Furthermore, we assessed effect sizes for self- and observer-rated measures separately, thus taking different observer perspectives into account. If necessary, we used other statistics reported than means and standard deviations (e.g., t or chi-square statistics) to calculate effect sizes (32). If studies included patients with and without personality disorders, effect sizes were calculated separately for both groups. There was a problem with the study of Woody et al. (13), which pooled the results of the two forms of therapy that were applied. Since the authors found no significant differences between the two forms of therapy applied, we decided to include this study and used the resulting pooled effect sizes as estimates for both forms of therapy. Since the differences between treatments were not significant, no systematic error is implied by this procedure. There was a similar problem with the study of Springer et al. (14), which did not report pre- and posttreatment means and standard deviations for the outcome measures. They reported t values of outcome data for the total sample of patients in the therapy and the control condition. Since they did not find significant differences between the therapy and the control condition in outcome measures, we decided to use these data to estimate the effect sizes of the inpatient cognitive behavior therapy condition. We included these studies so as not to reduce the already small number of studies. However, were these studies not included, the results would not change substantially.

Effect sizes are only one measure of effectiveness. The percentage of patients who recovered or in whom was seen a reliable or clinically significant change in the target measures is even more important. For this reason, we assessed rates of improvement whenever possible.

We calculated correlations between outcome and the following factors: length of therapy, patient gender, inpatient versus outpatient status, use of therapy manuals, clinical experience of therapists as reported in the studies, and study design (randomized versus naturalistic).

Results

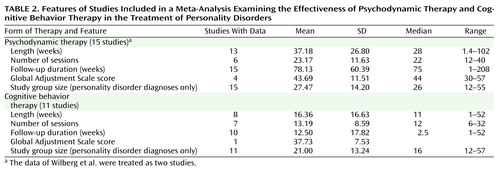

Fourteen studies of psychodynamic therapy (9, 10, 12, 13, 15–24) and 11 studies of cognitive behavior therapy (9, 10, 13, 14, 25–31) met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Two further studies examined the effects of psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapy combinations (35, 36).

Overview of Studies

Psychodynamic therapy

As will be subsequently described, the 14 studies of psychodynamic therapy used different forms. Psychoanalysis was not applied. In most of the studies, psychodynamic therapy was time-limited. The effects of outpatient individual psychodynamic therapy were examined in eight studies. Woody et al. (13) compared the effects of either 12 sessions of manualized supportive-expressive psychodynamic therapy (which used the Luborsky manual) or cognitive behavior therapy (per Beck), which were added to standard drug counseling. Stevenson and Meares (15) examined the outcome of a 1-year psychoanalytically oriented (self-psychological) regimen of outpatient psychotherapy. Therapy was conducted by trainees who received weekly supervision. Hoglend (16) studied the outcome of manualized psychodynamic focal therapy, which lasted an average of 27.5 sessions. Adherence to the manual was ensured. Winston et al. (17) compared short-term anxiety-provoking therapy (after Davenloo) to both another form of psychodynamic therapy (brief adaptive psychotherapy) and to a waiting list control condition. Each form of psychotherapy was administered for 40 weekly sessions. Manuals were used, and adherence was tested and ensured. Monsen et al. (19) studied a form of psychodynamic therapy that focused on object relations and self-psychology. Therapists were specially trained and supervised. Therapy lasted an average of 25 months. Munroe-Blum and Marziali (20) compared a time-limited group treatment with individual psychodynamic therapy. Each form of therapy lasted an average of 17 sessions. Manuals were used and adherence was ensured. Since the authors did not find significant differences between individual and group therapy, Munroe-Blum and Marziali (20) pooled the results of both conditions. However, the authors reported the results separately for the two conditions (personal communication, June 25, 2001). Since group therapy was based on an interpersonal rather than on a psychodynamic model, only the results reported for individual psychodynamic therapy were included in this review. Hardy et al. (10) compared the effects of manualized psychodynamic/interpersonal therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in depressed patients with and without cluster C personality disorders. In both forms of therapy, eight versus 16 sessions were applied. Diguer et al. (18) studied the effects of 16 sessions of supportive-expressive psychodynamic therapy (which followed Luborsky’s manual) in depressed outpatients with and without a personality disorder.

In three studies, psychodynamic treatment was applied within a partial hospitalization program for patients with personality disorders. Karterud et al. (12) examined psychodynamically oriented day hospital community treatment, which lasted for an average of 6 months. Wilberg et al. (21) reported the results of psychodynamic community day treatment with subsequent outpatient psychoanalytic group therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. These results were compared with a treatment-as-usual condition, i.e., psychodynamic day hospital treatment without group therapy. Since the authors had found significant differences between the two kinds of psychodynamic treatments, we assessed the effect sizes of the two treatments separately. Bateman and Fonagy (22) compared an analytically oriented partial hospitalization treatment program for borderline patients (maximum 18 months) with standard psychiatric care. Outcome data for an 18-month follow-up were recently reported (37).

Three studies examined the outcome of an inpatient psychodynamic treatment. Liberman and Eckman (9) compared insight-oriented therapy with behavioral therapy in the treatment of patients with repeated suicide attempts, each given for 32 sessions within a 10-day hospital treatment. Tucker et al. (23) studied the results of inpatient psychotherapeutic treatment that focused on interpersonal relations and intrapsychic organization. Patients were treated for an average of 8.4 months. Antikainen et al. (24) looked at the effects of inpatient psychotherapeutic community treatment for borderline patients that focused on the so-called split-type defense mechanisms. Treatment lasted for an average of 3 months.

Cognitive behavior therapy

Three of the aforementioned studies also reported data for the outcome of behavioral or cognitive behavior therapy (9, 10, 13). Eight other studies examined cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders. Linehan et al. (25) studied the interpersonal effects of dialectical behavior therapy. The manualized treatment lasted for 1 year and was compared with treatment as usual. This was true of another study of dialectical behavior therapy, which compared the effects of dialectical behavior therapy to treatment as usual in patients with borderline personality disorder who had comorbid drug dependence (26). Bohus et al. (27) applied dialectical behavior therapy to the inpatient treatment of female parasuicidal borderline patients that lasted for 3 months. In a randomized controlled study, Springer et al. (14) compared a modification of dialectical behavior therapy in an inpatient setting with a control condition. In this study, short-term group treatment was given to patients with personality disorders for 13 days (mean=6.3 sessions). Since it was not clear whether the applied form of therapy represented dialectical behavioral therapy, we prefer to regard it as a form of cognitive behavior therapy. Alden (28) examined three specific forms of cognitive behavior therapy treatments that were compared to a waiting list control condition. The manualized treatment consisted of 10 weekly group sessions. Adherence to the manuals was demonstrated by ratings of therapy sessions. Fahy et al. (29) studied cognitive behavior therapy in bulimia nervosa patients with and without personality disorders. The treatment lasted for 8 weeks. In a study by Stravynski et al. (30), outpatients with diffuse social phobia and avoidant personality disorder received 12 sessions of social skills training, either alone or combined with cognitive modification. Manuals were used, and ratings of therapy sessions were applied to ensure adherence to the manuals. Outcome did not differ significantly between the two therapies. For this reason, we assessed a mean overall effect size for the treatments. Brown et al. (31) studied the effects of cognitive behavior therapy in three groups of patients: patients with generalized social phobia (those with and those without avoidant personality disorder) and patients with nongeneralized social phobia. For this study, no data that allowed calculation of effect sizes in the form of Cohen’s d were provided; however, data referring to recovery were reported.

Psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapy combinations

Johnson et al. (35) studied a treatment that integrated cognitive behavior treatment of bulimic symptoms with psychodynamic therapy. They compared the outcome of borderline and nonborderline bulimic patients. As the pretreatment standard deviations were not published, we estimated the effect sizes conservatively by using the published t values (35, pp. 620–622). Ryle and Golynkina (36) examined the effects of time-limited cognitive-analytic therapy on a group of outpatients with borderline personality disorder. The outcome data of these two studies of combined therapies were treated separately in our meta-analysis.

Summary of Study Characteristics

Table 2 presents the length, number of sessions, follow-up duration, and other features of the psychodynamic and cognitive behavior studies. Treatment manuals were used in five studies of psychodynamic therapy (10, 13, 16–18) and in four studies that used cognitive behavior therapy only (25, 26, 28, 30). Stevenson and Meares (15) used weekly therapist supervision instead of a manual to ensure adherence to the applied form of therapy. This was true for Ryle and Golynkina (36), who in addition examined a measure of therapist competence. With a few exceptions (9), therapists had been specially trained in psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy. In two studies of psychodynamic therapy, therapies were conducted mostly by trainees (15, 21). Concurrent use of medication was reported in nine studies (10, 12, 13, 22, 24–27, 36).

Patient groups

Patients with borderline personality disorder were treated in seven of the psychodynamic therapy studies (9, 15, 20–24). Patients with borderline personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, and other personality disorders were studied by Karterud et al. (12). Mixed types from all three DSM-III personality disorder clusters were treated in two studies (17, 19). The patients in the study by Hoglend (16) had cluster B or C personality disorders. Hardy et al. (10) studied patients with major depression and a concomitant diagnosis of a cluster C personality disorder. Diguer et al. (18) reported the results of patients with major depression and a concomitant diagnosis of a personality disorder without specifying the types of personality disorders. Woody et al. (13) reported the results for opiate addicts with and without antisocial personality disorder. Thus, predominantly the severe forms of personality disorders (clusters A and B) were treated in most of the studies. Personality disorders predominantly of a neurotic level of dysfunction (cluster C) were treated in only two studies of psychodynamic therapy (10, 17). The study of Hoglend (16) included almost identical proportions of cluster C and cluster B patients (about 50% each).

In the seven studies using cognitive behavior therapy only, patients with borderline personality disorder (25–27), bulimia nervosa with and without personality disorder (29), and patients with avoidant personality disorder (28, 30, 31) were studied. Linehan et al. studied parasuicidal women with borderline personality disorder (25) and women with borderline personality disorder and drug dependence (26). Bohus et al. (27) reported the outcome for borderline inpatients. Springer et al. (14) examined a sample of inpatients with personality disorder, of which 50% were diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder.

Two studies required an axis I diagnosis of major depression as an inclusion criterion (10, 18), and for two studies opiate addiction or substance use disorder were required (13, 26). In one of the studies that used cognitive behavior therapy only, a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa was required (29); in two other studies, a diagnosis of social phobia was required (30, 31). In seven studies, information was given about the prevalence of comorbid axis I diagnoses (12, 13, 16, 17, 22, 26, 36). The most prevalent comorbid axis I diagnoses, in descending order, were depression (major depression or dysthymia), adjustment and anxiety disorders, substance abuse, somatoform disorder, and eating disorders.

Design and outcome measures

Three studies of psychodynamic therapy used randomized controlled designs with a waiting list or a nonspecific treatment condition (13, 17, 22). Four studies included randomized comparisons of two active treatments (9, 10, 13, 20). Of the studies using cognitive behavior therapy only, five studies applied randomized controlled designs (14, 25, 26, 28, 30). The other studies were naturalistic observations of therapy groups.

Three studies used only self-report outcome measures (9, 14, 17), two studies used only observer-rated measures (16, 24), and the other studies used both. The most frequently used self-report instruments were the Beck Depression Inventory (9, 10, 18, 20, 22, 24, 27) and the SCL-90-R (10, 12, 17, 19, 22, 27). The most frequently used observer-rated measures were the Health-Sickness Rating Scale and the Global Adjustment Scale (12, 16, 18, 23, 25). In all studies, observer-rated measures were assessed by using structured interview methods that were applied by independent assessors.

Effect Size Analyses

Psychodynamic therapy studies

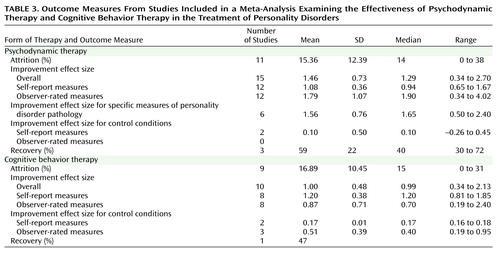

As seen in Table 3, psychodynamic therapy yielded an unweighted mean overall effect size of 1.46 (SD=0.73), which significantly differed from zero (t=7.73, df=14, p=0.0001). For self-report measures, the unweighted mean effect size was 1.08 (SD=0.36); for observer-rated measures, it was 1.79 (SD=1.07). These mean effect sizes both differed significantly from zero (self-report: t=10.51, df=11, p=0.0001; observer-rated: t=5.78, df=11, p=0.0001). Adjusted for sample size (34), the corresponding effect sizes were 1.40 (t=7.85, df=14, p<0.001), 1.03 (t=10.95, df=11, p=0.0001), and 1.71 (t=5.91, df=11, p=0.0001). In the two randomized controlled studies that reported data for the control condition (17, 22), active psychodynamic therapy was significantly more effective than the control conditions. For these two studies, the differences in within-condition effect sizes between psychodynamic therapy and the control condition yielded an unweighted mean difference of 1.32 for self-report measures. For observer-rated measures, only one study provided data that allowed comparison of active psychodynamic therapy with a control condition (22). We used the t and chi-square statistics reported by Bateman and Fonagy (22) to calculate effect sizes (32 [pp. 67, 223, 225]). Psychodynamic therapy yielded medium to large between-condition effect sizes for mean duration of inpatient episodes (d=4.29), number of individuals no longer self-mutilating (w=0.45), and number of individuals no longer parasuicidal (w=0.34).

Cognitive behavior therapy studies

For the 11 studies that used cognitive behavior therapy, there was a mean unweighted mean overall effect size of 1.00 (SD=0.48), which significantly differed from zero (t=6.56, df=9, p=0.0001). For self-report measures, the unweighted mean effect size was 1.20 (SD=0.38); for observer-rated measures, it was 0.87 (SD=0.71). These mean effect sizes both differed significantly from zero (self-report: t=8.95, df=7, p=0.0001; observer-rated: t=3.43, df=7, p=0.01). Adjusted for sample size (34), the corresponding effect sizes were 0.95 (t=6.67, df=9, p=0.0001), 1.14 (t=9.11, df=7, p=0.0001), and 0.82 (t=3.47, df=7, p=0.01). In three of the five randomized controlled studies (25, 26, 28), active cognitive behavior therapy was significantly more effective than the control conditions. In one study, no significant difference was found between cognitive behavior therapy and a discussion control group (14). For the three studies (25, 26, 28) that reported the relevant data, the differences in within-condition effect size between cognitive behavior therapy and the control condition yielded an unweighted mean difference of 0.81 for self-report measures and 0.50 for observer-rated measures. While these values correspond to medium to large effect sizes (32), the mean differences in effect sizes did not differ significantly from zero (t=4.76, df=1, p=0.13 and t=4.00, df=2, p=0.06, respectively) on account of the small number of studies. In the study of Linehan et al. (38), dialectical behavior therapy yielded a significantly greater reduction in parasuicidal acts than the control condition. We used the means and standard deviations reported by Linehan et al. to calculate effect sizes. For the reduction in parasuicidal acts, dialectical behavioral therapy yielded a medium between-condition effect size of 0.53.

In Table 4, the mean unweighted effect sizes for the most frequently used measures are presented. Effect sizes for both patients with and without personality disorders were assessed. For psychodynamic therapy, the largest effect sizes in personality disorders were found with the Health-Sickness Rating Scale or Global Adjustment Scale. For cognitive behavior therapy, the largest effect sizes were found with the Beck Depression Inventory.

Psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapy combination studies

For the two studies using combinations of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy (35, 36), we found a mean unweighted effect size for self-report measures of 0.79. Observer-rated measures data that allowed calculation of mean effect sizes in the form of Cohen’s d were not available.

Correlations of Measures and Recovery Rate

Self-rated and observer-rated measures showed a positive but nonsignificant correlation in studies of both psychodynamic therapy (rs=0.32, N=9, p=0.41) and cognitive behavior therapy (rs=0.26, N=6, p=0.62). However, for cognitive behavior therapy, only six studies provided both self-rated and observer-rated measures.

Three studies reported data referring to recovery from personality disorder after psychodynamic therapy, defined as no longer fulfilling the full criteria for personality disorder (15, 16, 19). Using these data, we calculated a mean recovery rate from personality disorders of 59% after a mean of 15 months of treatment. Concerning cognitive behavior therapy, only Brown et al. (31) reported data referring to recovery rates. After treatment, 47% of the patients were no longer diagnosed with avoidant personality disorder. These results and the definition of recovery, which is debatable, will be subsequently discussed.

Factors Influencing Outcome and Effect Size Analyses

Diagnosis

In eight studies, the effects of psychodynamic therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder were reported (9, 12, 15, 20–24). The mean unweighted overall effect size was 1.31 (SD=0.71). The mean unweighted effect sizes for self-rated and observer-rated measures were 1.00 (SD=0.25) and 1.45 (SD=1.09), respectively. These effect sizes were significantly different from zero (t=5.25, df=7, p=0.001; t=10.47, df=6, p=0.0001; t=3.28, df=5, p=0.02). The mean treatment duration was 33 weeks (SD=26.85). Adjusted for sample size, the corresponding effect sizes were 1.27 (t=5.18, df=7, p=0.001), 0.96 (t=10.27, df=6, p=0.0001), and 1.35 (t=3.47, df=5, p=0.02).

Four studies reported the effects of cognitive behavior therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder (14, 25–27). The mean unweighted overall effect size was 0.95 (SD=0.31). The mean unweighted effect sizes for self-rated and observer-rated measures were 0.97 (SD=0.24) and 0.81 (SD=0.54), respectively. The mean treatment duration was 22 weeks (SD=26.84). Adjusted for sample size, the corresponding effect sizes were 0.89, 0.92, and 0.76.

Core pathology of personality disorders

Some of the studies included measures that were more specific to personality disorders. For psychodynamic therapy, two studies reported results for the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (10, 22). Interpersonal problems are of some importance, since they are regarded as one of the core problems in personality disorders (39, also DSM-IV). For another measure of social functioning, the Social Adjustment Scale, outcome was reported by two other studies (17, 20). Monsen et al. (19) applied a measure of affect consciousness. They also reported data for the MMPI and for Morey’s Personality Disorder Scales, but these data were not included in our meta-analysis because effect sizes were not reported for all scales. Stevenson and Meares (15) reported outcome data referring to a measure of DSM-III criteria. Hardy et al. (10) applied a measure of self-esteem. Psychodynamic therapy yielded an unweighted mean effect size of 1.56 (SD=0.76) for these more specific measures of personality disorder pathology (Table 3). This mean effect size differs significantly from zero (t=5.02, df=5, p=0.004). Adjusted for sample size, the corresponding effect size is 1.50 (t=5.02, df=5, p=0.004).

For cognitive behavior therapy, two studies (10, 25) reported large effect sizes in more specific measures of personality disorder pathology (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, Social Adjustment Scale, self-esteem, and the anger trait subscale).

Treatment duration

For psychodynamic therapy, we found a positive correlation between the overall effect size and length of treatment, although it did not yield statistical significance because of the small number of studies (rs=0.41, N=13, p=0.16). For cognitive behavior therapy, no correlation was assessed because the number of studies providing data was too small (N=8). For the same reason, no correlations with the number of sessions were assessed.

Dropouts

Studies differed with regard to the kind of dropout data that were reported: subjects dropping out during the initial assessment phase (before therapy), during therapy, after therapy, or during the follow-up period. This is one reason why dropout rates varied considerably between studies. For psychodynamic therapy, the mean dropout rate was 15.36%; for cognitive behavior therapy, it was 16.89 (Table 3). For psychodynamic therapy, the dropout rate correlated significantly and positively with the presence of a cluster A or cluster B personality disorder (rs=0.72, N=9, p=0.03); for cognitive behavior therapy, the correlation was insignificant (rs=0.33, N=8, p=0.43). Contrary to Perry et al. (8), we did not find a significant correlation between length of therapy and dropout rate for either psychodynamic therapy (rs=–0.31, N=9, p=0.41) or cognitive behavior therapy (rs=0.31, N=6, p=0.54). Since the number of studies is very small, these results can only be preliminary.

Other factors

We tested for patient gender, inpatient versus outpatient status, use of therapy manuals, clinical experience of therapists, and study design. For psychodynamic therapy, the use of a therapy manual correlated significantly and positively with effect sizes for self-rated measures (rs=0.64, N=10, p=0.05). For observer-rated measures, no such correlation was found (rs=–0.17, N=11, p=0.61). None of the other variables correlated significantly with the outcome for either psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy.

Discussion

This review addressed the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders. One major limitation of this meta-analysis is the small number of studies that could be included: 14 studies of psychodynamic therapy and 11 studies of cognitive behavior therapy. The small number of studies reduces both the results’ potential generalization and the statistical power (32). Thus, the conclusions that can be drawn are only preliminary.

With regard to the potential generalization to community populations, the dropout rates are relevant. The mean dropout rates for psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy were 15% and 17%, respectively. These rates are below the dropout rate reported by the NIMH study of depression for patients with a personality disorder, which was 31%. The total number of subjects treated for personality disorders in the studies of psychodynamic therapy was N=417; for cognitive behavior therapy, the corresponding study group size was 231.

Since the data of the longest follow-up period were used for this review, the effect sizes indicate long-term rather than short-term change in personality disorders. This is particularly true of the psychodynamic therapy studies, which had a mean follow-up period of 1.5 years (78 weeks), whereas the mean follow-up period for the cognitive behavior therapy studies was considerably shorter (13 weeks).

The effect sizes cannot be compared directly between cognitive behavior therapy and psychodynamic therapy because the data do not come from the same experimental comparisons. The studies differed with respect to various aspects of therapy, patient samples, outcome assessment, and other variables.

Within-group effect sizes may be an overestimate of the true change because of unspecific therapeutic factors, spontaneous remission, or regression to the mean. However, in the two randomized controlled studies of psychodynamic therapy (17, 22), the mean effect sizes for psychodynamic therapy exceeded that of the control condition. This was also true for the patients of the Bateman and Fonagy study in an 18-month follow-up (37). For cognitive behavior therapy, three randomized controlled studies (25, 26, 28) reported that cognitive behavior therapy was superior to a control condition.

The most frequently used outcome measures were the Beck Depression Inventory, SCL-90-R, and Global Adjustment Scale/Health-Sickness Rating Scale, which are broad measures of symptom severity and level of functioning and are nonspecific in nature. Thus, it is not clear from the data of these instruments if the corresponding effect sizes refer to changes in the personality disorders themselves or to improvements in axis I psychopathology. According to the results of this meta-analysis, both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy yielded significant improvements in more specific measures of personality disorder pathology.

Most of the patients studied who had personality disorders had comorbid axis I pathology. This is especially true of severe personality disorders such as borderline personality disorder. Studies that included patients with both axis I and axis II pathology (10, 12, 18) reported more pathological pretreatment scores (SCL-90-R global severity index, Health-Sickness Rating Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Present State Examination) for patients with personality disorders than for patients who had axis I pathology only.

Three studies of psychodynamic therapy reported rates of recovery from personality disorders. The mean recovery rate was 59%. However, defining remission as no longer meeting the criteria of the disorder at a single point in time is debatable. Significant fluctuations over time may occur that may be state dependent rather than showing lasting remission of the personality disorder in question (40–42). Long-term follow-up evaluations are necessary to study recovery from personality disorders.

Several studies reported more improvement in personality disorder patients after longer treatment durations (12, 16, 43). These results are consistent with the findings reported by Shea et al. (44) and Diguer et al. (18) for depressive patients with and without personality disorders and with the results of Kopta et al. (45), who found that improvements in character problems take longer than symptom changes. For patients with avoidant personality disorder, Alden (28) noted that changes patients made during a 10-week treatment were insufficient to consider them healthy. Perry et al. (8) estimated the length of treatment necessary for patients to no longer meet the full criteria for a personality disorder (recovery). According to these estimates, 50% of patients with a personality disorder would recover by 1.3 years or 92 sessions and 75% by 2.2 years or about 216 sessions. Certainly, these estimates can only be preliminary, and more studies are necessary to test if these estimates can be generalized.

There is evidence that treatment with psychotherapy in personality disorder patients is relevant to the cost of health care utilization. In a randomized controlled study of high utilizers of psychiatric services, Guthrie et al. (46) showed that short-term psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy was significantly superior to treatment as usual with regard to the reduction of distress and the cost of health care utilization. Since certain subgroups of patients with personality disorders are high utilizers of psychiatric services (e.g., patients with borderline personality disorder), these results are relevant for the treatment of personality disorders with psychotherapy.

In a recent meta-analysis, psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy proved to be equally effective treatments for depression (47). According to the results presented in this review, there is evidence that psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy are effective treatments of personality disorders. Further research should examine specific forms of psychotherapy for specific types of personality disorder. In order to ensure both internal and external validity, both naturalistic and randomized controlled studies are necessary. Outcome measures should focus not only on axis I pathology but also on core psychopathology. Data on health economics should be included.

|

|

|

|

Received Nov. 14, 2001; revisions received May 3, Aug. 29, and Oct. 21, 2002; accepted Nov. 5, 2002. From the Department of Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University of Göttingen; and the Tiefenbrunn Clinic, Göttingen, Germany. Address reprint requests to Dr. Leichsenring, Department of Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University of Göttingen, von-Siebold-Str. 5, 37075 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Livesley WJ, Schroeder ML, Jackson DN, Jang KJ: Categorical distinctions in the study of personality disorder: implications for classification. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:6-17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Livesley WJ, Jang KL: Toward an empirically based classification of personality disorder. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:137-151Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Perry JC, Lavori PH, Hoke L: A Marcov model for predicting levels of psychiatric service use in borderline and antisocial personality disorders and bipolar type II affective disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1987; 21:215-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Dolan BM, Warren FM, Menzies D, Norton K: Cost-offset following specialist treatment of severe personality disorders. Psychiatr Bull 1996; 20:413-417Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Oldham JM, Gunderson JG: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:295-302Link, Google Scholar

6. Gunderson JG, Zanarini M: Current overview of the borderline diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48(Aug suppl):5-14Google Scholar

7. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of psychotherapeutic treatment of personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:138-143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Perry JC, Banon E, Ianni F: Effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1312-1321Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Libermann RP, Eckman T: Behavior therapy vs insight oriented therapy for repeated suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:1126-1130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hardy GE, Barkham M, Shapiro DA, Stiles WB, Rees A, Reynolds S: Impact of cluster C personality disorders on outcomes of contrasting brief psychotherapies for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:997-1004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Stone M: Psychotherapy with schizotypal borderline patients. J Am Acad Psychoanal 1983; 11:87-111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Karterud S, Vaglum S, Friis S, Irion T, Johns S, Vaglum P: Day, hospital therapeutic community treatment for patients with personality disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:238-243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Woody GE, McLellan T, Luborsky LL, O’Brien CP: Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:1081-1086Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Springer T, Lohr N, Buchtel HA, Silk KR: A preliminary report of short-term cognitive-behavioral group therapy for inpatients with personality disorders. J Psychother Pract Res 1996; 5:57-71Medline, Google Scholar

15. Stevenson J, Meares R: An outcome study of psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:358-362Link, Google Scholar

16. Hoglend P: Personality disorders and long-term outcome after brief psychodynamic therapy. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:168-181Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Winston A, Laikin M, Pollack J, Samstag LW, McCullough L, Muran JC: Short-term psychotherapy of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:190-194Link, Google Scholar

18. Diguer L, Barber JP, Luborsky L: Three concomitants: personality disorders, psychiatric severity, and outcome of dynamic psychotherapy of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1246-1248Link, Google Scholar

19. Monsen JT, Odland T, Faugli A, Daae E, Eilertsen DE: Personality disorders: changes and stability after intensive psychotherapy focusing on affect consciousness. Psychother Res 1995; 5:33-48Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Munroe-Blum H, Marziali E: A controlled trial of short-term group treatment for borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1995; 9:190-198Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Wilberg T, Friis S, Karterud D, Mehlum L, Urnes O, Vaglum P: Outpatient group psychotherapy: a valuable continuation treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder treated in a day hospital? Nord J Psychiatry 1998; 52:213-221Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1563-1569Link, Google Scholar

23. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, Harlam D, Sher I: Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1443-1448Link, Google Scholar

24. Antikainen R, Hintikka J, Lehtonen J, Koponen H, Arstila A: A prospective follow-up study of borderline personality disorder inpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:327-335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1771-1776Link, Google Scholar

26. Linehan MM, Schmidt H, Dimeff LA, Craft JC, Kanter J, Comtois KA: Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. Am J Addict 1999; 8:279-292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Bohus M, Haaf B, Stiglmayr C, Pohl U, Böhme R, Linehan M: Evaluation of inpatient dialectical-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder—a prospective study. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:875-887Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Alden L: Short-term structured treatment for avoidant personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 56:756-764Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Fahy TA, Eisler I, Russell GFM: Personality disorder and treatment response in bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:765-770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Stravynski A, Marks I, Yule W: Social skills problems in neurotic outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:1378-1385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Brown EJ, Heimberg RG, Juster HR: Social phobia subtype and avoidant personality disorder: effect of severity of social phobia, impairment, and outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behav Ther 1995; 26:467-486Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

33. Rosenthal R: Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research: Applied Social Research Methods. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1991Google Scholar

34. Hedges LV, Olkin I: Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. New York, Academic Press, 1985Google Scholar

35. Johnson C, Tobin DL, Dennis A: Differences in treatment outcome between borderline and nonborderline bulimics at one-year follow-up. Int J Eat Disord 1990; 9:617-627Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Ryle A, Golynkina K: Effectiveness of time-limited cognitive-analytic therapy for borderline personality disorders: factors associated with outcome. Br J Med Psychol 2000; 73:197-210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:36-42Link, Google Scholar

38. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard H: Cognitive behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060-1064Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Benjamin L: Interpersonal Diagnosis and the Treatment of Personality Disorders, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 1996Google Scholar

40. Kullgren G, Armelius BA: The concept of personality organization: a long-term comparative follow-up study with special reference to borderline personality organization. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:203-212Crossref, Google Scholar

41. McGlashan TH: The Chestnut Lodge Follow-Up Study, III: long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:20-30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Pope HG Jr, Jonas JM, Hudson JI, Cohen BM, Gunderson JG: The validity of DSM-III borderline personality disorder: a phenomenologic, family history, treatment response, and long-term follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:23-30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Dolan BM, Warren F, Norton K: Change in borderline symptoms one year after therapeutic community treatment for severe personality disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:274-279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin I, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP: Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:711-718Link, Google Scholar

45. Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, Beutler LE: Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:1009-1016Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Guthrie E, Moorey J, Margison F, Barker H, Palmer S, McGrath G, Tomenson B, Creed F: Cost-effectiveness of brief psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy in high utilizers of psychiatric services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:519-526Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Leichsenring F: Comparative effects of short-term psychodynamic therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21:401-419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar