Effectiveness of Psychotherapy for Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders in psychotherapy outcome studies. METHOD: Fifteen studies were located that reported data on pretreatment-to-postreatment effects and/or recovery at follow-up, including three randomized, controlled treatment trials, three randomized comparisons of active treatments, and nine uncontrolled observational studies. They included psychodynamic/interpersonal, cognitive behavior, mixed, and supportive therapies. RESULTS: All studies reported improvement in personality disorders with psychotherapy. The mean pre-post effect sizes within treatments were large: 1.11 for self-report measures and 1.29 for observational measures. Among the three randomized, controlled treatment trials, active psychotherapy was more effective than no treatment according to self-report measures. In four studies, a mean of 52% of patients remaining in therapy recovered—defined as no longer meeting the full criteria for personality disorder—after a mean of 1.3 years of treatment. A heuristic model based on these findings estimated that 25.8% of personality disorder patients recovered per year of therapy, a rate sevenfold larger than that in a published model of the natural history of borderline personality disorder (3.7% recovered per year, with recovery of 50% of patients requiring 10.5 years of naturalistic follow-up). CONCLUSIONS: Psychotherapy is an effective treatment for personality disorders and may be associated with up to a sevenfold faster rate of recovery in comparison with the natural history of disorders. Future studies should examine specific therapies for specific personality disorders, using more uniform assessment of core pathology and outcome.

Individuals with personality disorders have pervasive and long-standing traits affecting their perception and thinking about themselves and others, their impulse and affect regulation, and their interpersonal and other social role functioning. Their long-standing impairment in functioning and their personal distress are well documented (1–4). They are also heavy users of mental health resources (5). Nonetheless, there is a paucity of empirical studies examining the outcome of personality disorders treated with psychotherapy, with few controlled studies. Given current concerns about cost containment and accountability, there is reason to examine the evidence to date for the efficacy of psychotherapy for personality disorders. This need for evidence of efficacy applies also to psychopharmacologic treatments for personality disorders, which have tended to produce exciting findings in early and/or open studies followed by more disappointing or equivocal findings in later and/or more-controlled studies (6). We considered it timely to review the small but growing empirical literature on the outcome of personality disorders treated with psychotherapy. While controlled treatment studies are few, systematic examination of these along with naturalistic treatment studies may reveal consistent findings relevant to the efficacy of psychotherapy for personality disorders.

We found 15 studies reporting empirical data on the outcome of personality disorders after either short- or long-term psychotherapy that fitted our criteria for analysis. These studies used a variety of both observer- and self-rated outcome measures, assessing response to treatment at follow-ups of variable durations. Taking these differences across studies into account, we addressed four questions. 1) What is the evidence for improvement in symptoms, social role functioning, or core psychopathology after psychotherapy? 2) Do different patterns of change emerge when one compares observer-rated and self-rated outcome measures? 3) What is the relation between treatment duration and the amount of improvement? 4) What is the evidence that individuals with personality disorders recover following psychotherapy, and how long does it take?

There is a widely held belief that personality disorders are intractable to psychotherapy. This review should help clinicians test this belief against the available empirical evidence. We also hope that the findings will stimulate further research to improve the psychotherapeutic treatments currently available.

METHOD

We collected reports of empirical outcome studies on the psychotherapy of personality disorders that were published from 1974 to 1998, using computer searches (MEDLINE and PsycINFO) supplemented by a manual search. We included studies that 1) used systematic methods to make personality disorder diagnoses, 2) used validated outcome assessments, and 3) reported data that allowed either calculation of within-condition effect sizes or determination of recovery from the personality disorder. Given the potential for systematic differences due to measurement perspective (7), we examined self-report and observer-rated outcome measures separately. Whenever the data were available, we examined the percentage of subjects with personality disorders who recovered versus time in treatment. When multiple reports were available from the same study, we selected the one with the longest posttreatment follow-up. Fifteen studies (8–22) met these inclusion criteria.

Because different studies used different outcome measures, durations of treatment, and follow-up periods, we converted their results into effect sizes to facilitate comparing results across studies. In a randomized, controlled treatment trial, the usual way of calculating an effect size for a given measure represents whether the final mean scores of the experimental and control treatment groups differ. The difference between these means at the end of treatment is then divided by the standard deviation of the difference between the pretreatment score and the posttreatment score of all subjects. This number represents the degree to which the results deviate from the null hypothesis. Cohen (23, p. 40) considers the magnitude of such effect sizes to be interpretable as follows: 0.20=small effect, 0.50=medium, and 0.80=large.

The 15 studies required us to make the following deviations from the method described above. First, there were only three randomized, controlled treatment trials (10, 16, 17). The remaining studies presented naturalistic observations of patient groups in treatment or comparisons of two active treatments. We adjusted for this by calculating within-condition effect sizes for all studies. We subtracted the pretreatment score from the posttreatment score for each measure and then divided by the standard deviation of the score at intake. As appropriate, signs were reversed so that a positive effect size always indicated improvement. Because this method does not adjust for change that might occur in the control group of a randomized, controlled treatment trial, the magnitude of the effect size may be different than it would be with the use of Cohen’s method.

In the randomized, controlled treatment trials (10, 16, 17), because the comparison groups were small and usually of unequal size, the standard deviations at baseline often varied between the comparison groups. Using the smaller of two standard deviations in the denominator would yield a larger effect size. To make the effect sizes more comparable across studies, whenever there was more than one patient group, we calculated a pooled baseline standard deviation, which has also been suggested by Rosenthal (24).

We were interested in long-term change and, therefore, examined results at the last follow-up. Whenever studies included multiple measures, we calculated the effect size for each measure separately, then reported the median values of the effect sizes for the self-report and observer-rated measures, thus summarizing the study’s overall results. We then examined the relationships between other variables of interest, such as duration of treatment, and these summary effect sizes, using nonparametric Spearman correlations. Data on recovery from a personality disorder were plotted as a function of treatment duration, and then number of treatment sessions, with the use of simple linear regression to estimate the percentage of each study group that had recovered at follow-up. Survival analysis was not used because the unit of observation was the study group rather than the individual case. Finally, the number of studies meeting our criteria was relatively small, and therefore statistical power was quite low. Not including analyses for potential confounders and follow-up analyses, we planned eight a priori tests for the four hypotheses. The Bonferroni correction would set alpha at p=0.006, although given the interdependence of the outcomes, this may be too conservative. We present statistical trends (e.g., p>0.05) alongside significant findings in order not to overlook potentially important findings and to make the best use of the data for heuristic purposes.

RESULTS

Description of Studies

The 15 studies differed with respect to the characteristics of the patients, the treatments, and the study designs.

Patients

Four studies (8, 11, 17, 19) focused largely on borderline personality disorder, one (12) mostly on borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder, two on other specific types—avoidant (10) and antisocial (9)—and eight (13–16, 18, 20–22) on mixed types from one to all three clusters of DSM personality disorders. Thirteen studies involved outpatients, while one study (8) involved hospitalized patients and one (12) day hospital patients. Most study subjects were self-referred. Potential sources of selection bias were largely unreported.

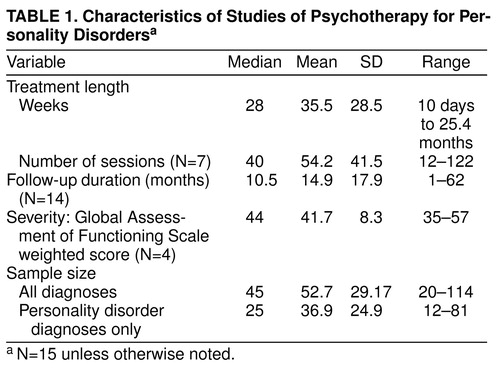

Four studies reported severity of illness at intake as the mean score on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) or the Health-Sickness Rating Scale (in Karterud et al. [12], the mean Health-Sickness Rating Scale score=40; in Hoglend [14; and personal communication, 1996], the mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score=57; in Diguer et al. [15], the mean Health-Sickness Rating Scale score=47.5; and in Linehan et al. [17], the mean GAS score=35). This yielded an overall weighted mean score of 41.7 (table 1), which falls in the low DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score range of 41–50, characterized by “serious symptoms…OR any serious impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning.”

Four studies required the presence of an axis I disorder for inclusion, specifically, opiate dependence (9), bulimia nervosa (13), or major depression (15, 21). Four studies (9, 12, 14, 16) listed the overall prevalence of one or more comorbid axis I diagnoses other than those required for inclusion, yielding a mean of 63.8% (SD=21.7%). The most prevalent diagnoses, in descending order, were mood, adjustment, anxiety, substance, somatoform, other, and eating disorders.

Treatment modality and duration

Six studies (11, 12, 14–16, 18) used dynamic psychotherapy, three (10, 13, 17) used cognitive behavior therapy, and three (8, 9, 21) compared the two. One (22) examined supportive psychotherapy. Two (19, 20) studied interpersonal group therapy, one of which (19) included an individual dynamic control therapy but pooled the results.

Among studies of dynamic treatments, Stevenson and Meares (11) looked at the effects of a 1-year course of twice-weekly dynamic psychotherapy based on self psychology theory. Karterud et al. (12) examined the outcome of long-term dynamic psychotherapy in a 6-month day hospital program. Hoglend (14) studied the effects of intermediate-term dynamic psychotherapy lasting an average of 27.5 sessions. Winston et al. (16) examined the differential effectiveness of two dynamic therapies—short-term anxiety-provoking psychotherapy and brief adaptive psychotherapy—each given for 40 weeks—compared with a 15-week waiting-list control condition before treatment for the same patients. Monsen et al. (18) looked at the effect of intensive psychodynamic psychotherapy, based on self psychology and an object relations model, administered for an average of 25.4 months.

Among studies of cognitive behavior treatments, Linehan et al. (17) studied the effects of dialectical behavior therapy on parasuicidal women with borderline personality disorder, treated for 1 year, compared with unspecified, community “treatment as usual.” Alden (10) studied three types of short-term behavioral therapy—graded exposure, graded exposure plus social skills training, and graded exposure plus social skills training plus an intimacy focus—administered over 10 weeks, compared with a waiting-list control group. Having found no significant differences among active treatments, she compared the pooled results with those from the control group. Fahy et al. (13) compared the outcome, after 8 weeks of cognitive behavior therapy, of patients with bulimia nervosa with and without a comorbid personality disorder.

Liberman and Eckman (8) compared the effects of insight-oriented psychotherapy and behavioral therapy in a 10-day hospitalization program. Woody et al. (9) compared the effects of adding either supportive-expressive or cognitive behavior psychotherapy to drug counseling among opiate addicts for 24 weeks. The two types of psychotherapy were of equal efficacy, so the researchers compared the pooled results with those of drug counseling alone. Hardy et al. (21) compared dynamic/interpersonal and cognitive behavior therapies for outpatients with a major depressive episode, with or without a personality disorder, over either 8 or 16 weeks. The two therapies were generally equally effective.

Rosenthal et al. (22) treated individuals with cluster C personality disorders with 40 sessions of supportive psychotherapy.

Monroe-Blum and Marziali (19) compared interpersonal group psychotherapy for 35 weeks with open-ended individual dynamic psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Budman et al. (20) conducted 72 90-minute sessions of interpersonal group psychotherapy over 18 months.

Nine studies (9, 14–17, 19–22) used explicit treatment manuals. Stevenson and Meares (11) used weekly seminars and therapist supervision instead of a manual to increase adherence to a particular type of therapy.

Concurrent use of medication was rarely reported. Woody et al. (9) reported that all subjects were on methadone maintenance. Linehan et al. (17) reported less use of psychotropic medication by the experimental group than by the treatment-as-usual group at follow-up.

Treatment duration was highly variable, with a median of 28 weeks and a median of 40 sessions (Table 1). Follow-up was done in 14 studies, with a median of 10.5 months. Frequency of sessions varied from daily, for inpatients (8) and day hospital patients (12), to once or twice weekly for outpatient psychotherapies (9–11, 13–22).

Study designs

Three studies (10, 16, 17) were randomized, controlled treatment trials with a waiting-list or nonspecific treatment condition; three (8, 19, 21) were randomized comparisons of two active treatments, although one (19) pooled the results of the comparison groups. Stevenson and Meares (11) used a patient-as-own-control design, comparing their sample 1 year before and 1 year after active treatment. The other studies (9, 12–15, 18, 20, 22) reported naturalistic observation of treatment groups.

Outcome measures

Three studies (13, 16, 22) reported only self-rated measures, and two (14, 20) only observer-rated measures, while the remaining ones (9–12, 15, 17–19, 21) reported both. The most frequently used self-report outcome measures were the Symptom Checklist-90-R, target complaints, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, and the Beck Depression Inventory. The most frequent observer-rated measures were the Health-Sickness Rating Scale or the GAS and the Social Adjustment Scale. Two studies (14, 18) measured dynamic change with the use of reliable, valid measures.

Substantive Findings

Retention-attrition

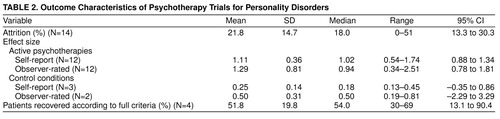

The percentages of dropouts varied greatly, with a mean of 21.8% (table 2). The highest percentages of dropouts, 42% and 51%, were found in the two longer-term group therapy conditions (19, 20). The five shorter-duration treatments (16 weeks or less) had fewer dropouts than did the nine longer-duration treatments (8.2% versus 29.3%; t=3.54, df=12, p=0.004). When duration was controlled, dropout rate did not correlate significantly with other study variables, including effect sizes.

Effect sizes

At follow-up, active psychotherapies for personality disorder groups yielded unweighted mean effect sizes of 1.11 for self-report measures and 1.29 for observer-rated measures (table 2). These mean effect sizes were significantly greater than zero for both self-report measures (t=10.75, df=10, p=0.0001) and observer-rated measures (t=5.55, df=11, p=0.0002). By contrast, waiting-list or treatment-as-usual control conditions yielded lower unweighted mean effect sizes at follow-up or at the end of the waiting-list period (Table 2). However, these probability estimates did not take into account the fact that some improvement might have been due to regression to the mean. Among the three randomized, controlled treatment trials, the differences in within-condition effect size between psychotherapy and the control condition for self-report measures yielded an unweighted mean difference of 0.75, which is significantly greater than zero (t=13.18, df=2, p=0.006). The mean difference in effect sizes weighted by sample size was 0.78 (t=21.03, df=2, p=0.002). Among the two randomized, controlled treatment trials reporting observer-rated measures, the differences in effect size yielded an unweighted mean difference of 0.50 (t=4.54, df=1, p=0.14); the mean difference in effect size weighted by sample size was 0.57 (t=7.43, df=1, p=0.085). Finally, no differences were attributable to study design for either self-report (F=1.63, df=2, 9, p=0.24) or observer-rated (F=0.14, df=2, 9, p=0.87) effect sizes.

One concern is a possible publication bias against studies reporting negative findings, the so-called “file-drawer problem” (24, 25). To consider this, we calculated the effect of potential unpublished studies by assuming a zero difference in effect size between active therapy and the control condition. Adding one such study would diminish our self-report findings to a trend (t=2.93, df=3, p=0.06), which would persist even if the other 12 of our 15 studies had been randomized, controlled treatment trials with unreported null effects (t=1.86, df=14, p=0.08).

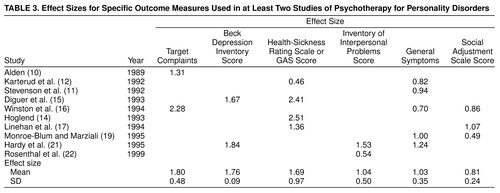

Table 3 displays the mean effect sizes for measures used in two or more studies. The largest were for self-report target complaints, the Beck Depression Inventory scores in the two depressed samples, and observer-rated global functioning. Next came two self-reports: the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems and general symptoms. The lowest was for ratings of social adjustment (e.g., the Social Adjustment Scale). In addition, Karterud et al. (12) reported change on the Health-Sickness Rating Scale by personality disorder type, in increasing magnitude of effect size: schizotypal personality disorder (–0.03), borderline personality disorder (0.45), other largely cluster C personality disorders (0.96), and patients without a personality disorder (1.46). Diguer et al. (15) also reported higher effect sizes for patients without a personality disorder than for those with a personality disorder. These differences suggest that diagnosis influences change in global functioning. Finally, the two studies requiring major depression reported larger mean effect sizes than the remaining 13 studies for both self-report measures (mean=1.17 versus mean=0.99; t=3.86, df=10, p=0.003) and observer-rated measures (mean=2.29 versus mean=1.10; t=2.20, df=10, p=0.05).

Treatment duration and effect sizes

The correlation between duration and effect size was negative for self-reported outcomes (rs=–0.46, N=12, p=0.13), whereas it was positive for observer-rated outcomes (rs=0.14, N=12, p=0.66). However, when length of follow-up was partialed out, self-report effect size correlated with treatment duration (rs=–0.71, N=9, p=0.04), while observer-rated effect size was still nonsignificant. Following up on this, we compared the mean self-report effect sizes of the five shorter-term studies (16 weeks or less) with those of the seven longer-term studies (mean=1.38 versus mean=0.92; t=2.86, df=10, p=0.02). The larger self-report effect size for the shorter-term treatments raises the question of whether self-report measures reflect some transient change that diminishes with longer treatments, something not found with observer-rated measures.

Recovery from personality disorder

Four studies (11, 14, 18, 20) reported the percentage of subjects no longer meeting criteria for a personality disorder at follow-up (table 2). All used medium- to long-term dynamic/interpersonal therapies. The diagnostic composition of the study groups included cluster B and C patients, with 53% (N=42 of 79) having borderline personality disorder. The mean proportion recovered was 51.8% (t=5.23, df=3, p=0.01) after a mean of 78 sessions over a mean of 67 weeks (1.3 years).

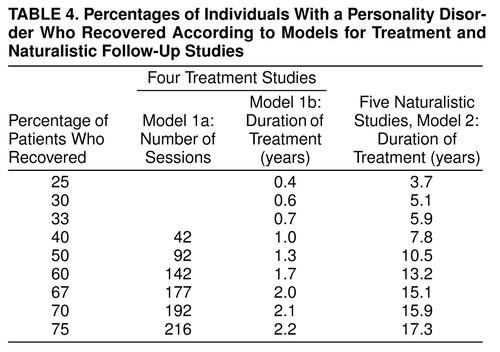

We examined percentage recovered as a function of treatment length. Inspection of a scatterplot indicated a relationship between these two variables (somewhat less so with number of sessions). We performed simple linear regressions predicting the percentage of patients in each sample who recovered, weighted by sample size, by entering the number of therapy sessions (model 1a) and treatment duration in years (model 1b). While neither model was statistically significant, they allowed us to calculate the hypothetical values for the treatment duration associated with recovery for a range of 25%–75% of cases, the approximate range of the studies’ observations. We then compared these models with a similar linear regression model derived from five natural history (not treatment) studies of recovery from borderline personality disorder previously published by the first author (1). Table 4 displays the results of this comparison.

The natural history studies of borderline personality disorder (model 2) yielded an estimated recovery rate of 3.7% per year (t=3.30, df=3, p=0.05; 95% CI=0.14%–7.28%). On the basis of the four active treatment studies, model 1b produced a recovery rate of 25.8% per year (t=1.98, df=2, p=0.19; 95%CI=–5.8%– 67.4%), a rate seven times greater than that observed in the naturalistic follow-up studies. Model 1a indicated a recovery rate of 0.20% of cases per therapy session (t=0.55, df=2, p=0.64; 95% CI=–0.96%–1.36%). The 95% confidence intervals for models 1a and 1b include a recovery rate of zero. This indicates that while these models can serve heuristic purposes, they should not be accepted as validated. In table 4, models 1a and 1b suggest that 92 treatment sessions or 1.3 years of treatment would yield recovery from personality disorder according to the full criteria in 50% of mixed personality disorder subjects. By comparison, model 2 suggests that 10.5 years of naturalistic follow-up would yield recovery in 50% of subjects with borderline personality disorder. All models included only subjects still in follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Limitations of the Review

The major limitation of this review is the availability of only 15 studies from which our conclusions are derived. This is especially problematic given differences across studies in diagnoses, severity of illness, design, treatment modality and duration, and assessment methods. However, by using meta-analysis we were able to detect some consistent patterns. Nonetheless, further validation and detection of more specific effects will require substantially more studies. Meta-analysis itself has limitations (25), such as equating studies within broad categories (e.g., dynamic or cognitive behavior therapy), which may obscure meaningful differences within treatment modalities (26).

Another concern is generalizability to community populations seeking treatment. Patients not referred to a study, refusing to join, or dropping out before follow-up may differ in some significant way from patients admitted to and continuing in treatment. Any bias would limit generalization from these findings. This may be especially problematic when one is considering the results from a few studies, as we have done in comparing recovery from personality disorders. Few studies reported these data. In one exception, Stevenson and Meares (11), reported that 48 (81%) of 59 eligible patients joined the study, 11 (23%) of the 48 dropped out, and a further seven (15%) were omitted from analyses because they decided to continue treatment beyond the 1-year study period. While intention-to-treat analyses would mitigate the effects of bias due to dropout, patients with personality disorders often drop out from follow-up assessments as well as treatment.

Treatment dropouts represent a special case of the potential for bias. The percentage of dropouts was significantly lower for treatments of shorter duration than for those of longer duration. After control for duration of treatment, the percentage of dropouts did not correlate with other study variables, decreasing the likelihood that dropout was a source of bias in our overall results. The overall mean rate of attrition (21%) compares favorably with that of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (27), which had a 31% dropout rate for personality disorders across all treatments, with the largest for clusters B (40%) and A (36%) and the lowest for cluster C (28%). The mean dropout rate of 28% for our longer-duration treatment studies is comparable to the mean dropout rate of 28% for the natural history follow-up studies (1). This suggests that the present treatment studies were at no higher risk for bias due to dropout than these other studies of personality disorders. However, patient characteristics that predict dropout should be examined.

It is interesting that subjects with borderline personality disorder who agreed to participate in a randomized, controlled treatment trial comparing group therapy with individual therapy (19) had a high dropout rate even before treatment began, after learning of their random treatment assignment (9% refused individual therapy and 19% group therapy, 28% total), as well as during the course of therapy (39% of those accepting assignment). In both cases the dropout rate was higher for group therapy. Budman et al. (20) reported that 51% of patients dropped out of group therapy, especially those with borderline personality disorder. These investigators subsequently modified their treatment model to include individual sessions for patients with borderline personality disorder, similar to the model of Linehan et al. (17). This suggests that acceptability to patients is a problem for group therapy in comparison with individual treatments. Further study is warranted, given the popularity of the group modality as a response to concerns about the cost of treatment. If limitation of treatment choice results in a high proportion of treatment refusal, especially for patients with borderline personality disorder, then clinical settings may ipso facto exclude patients needing treatment.

There was much heterogeneity in sample selection, including differences in personality disorder types, severity of illness, comorbidity, and treatment setting. Generally, cluster A disorders were least represented. Cluster B and C disorders were about equally represented, with cluster C disorders generally involving less impairment. However, the single type most often studied was borderline personality disorder. Thus, most of our conclusions are generalizable to a mix of personality disorder types with a high proportion of borderline patients.

The heterogeneity of diagnostic assessments across studies hampers comparison. This is worsened by the demonstrated lack of agreement between most diagnostic instruments when they have been compared (4, 28, 29). However, whenever a high proportion of studies report similar findings despite such differences, it indicates a robust finding or signal, despite the noise. This is the case here.

The confounding of personality disorder types with treatment types and duration of treatment makes it difficult to conclude that any one type of treatment consistently demonstrates greater effects than no treatment or a comparison treatment. However, in the randomized, controlled treatment trials, all experimental treatments were superior to waiting-list or control treatment conditions.

The studies assessed outcome in a variety of ways, with no single measure used by most studies. While most studies included both self-report and observer-rated measurement perspectives, several used only one. Finally, in many instances it was not clear how clinically significant the results were, or whether the patients improved into a healthy range of scores.

Using pretreatment and posttreatment within-condition effect sizes permitted direct comparison of studies with different personality disorder diagnoses, study designs, outcome measures, and treatments, given that most lacked control/comparison groups. Lack of such a strategy makes meaningful summary even more difficult (30). One criticism is that the conclusions about effect size may lack specific meaning. However, the degree of improvement was sizable for all measures in Table 3, so averaging them was also reasonable.

Within-condition effect sizes may overestimate true change, not adjusting for change due to attention alone, time, or regression toward the mean. However, using this approach for the three randomized, controlled treatment trials, we found larger effect sizes for active psychotherapy than for waiting-list or control treatments—differences of moderate to large magnitude, albeit significant only for self-report measures. Our analyses confirmed the original authors’ findings that each active treatment had significantly greater efficacy than the control conditions.

Major Findings

Positive effects of psychotherapy

All studies of active psychotherapies of personality disorders reported positive outcomes at termination and at follow-up. The within-condition effect sizes were large for both self-report and observer-rated measures (mean=1.11 and mean=1.29, respectively), although not necessarily comparable to what Cohen (23) considered large for between-condition comparisons. Effect sizes for the randomized, controlled treatment trials did not differ significantly from those for the uncontrolled studies. This lessens the possibility that the uncontrolled studies inflated the overall effect sizes. The control conditions in the randomized, controlled treatment trials produced only small to medium within-condition effects, and the differences between subjects receiving active psychotherapy and control subjects were significant for self-report measures, whereas they were of lower magnitude and significance for observer-rated measures. Although our findings are based on only 15 studies, we consider them to be robust for the following reasons. The results are highly consistent across both controlled and uncontrolled studies despite widely varying designs. They are also consistent with findings in the general psychotherapy literature that active treatment is more effective than no treatment or minimal treatment (31).

One caveat is the possibility that there could be other randomized, controlled treatment trials with negative findings that are still unpublished. Hypothetically, we calculated that one additional study with zero difference in effect would diminish the significance of our finding for self-report measures to p=0.06. However, Petitti (32, p. 130) has noted a problem with the assumption that the effect is zero, when the current evidence is otherwise, and does not recommend this approach. Further empirical reassurance on this issue can be found from two additional randomized, controlled trials (27, 33). Although they were not included in this review because of incomplete data for calculating effect sizes (27) or failure to analyze groups with and without personality disorders separately (33), these studies did find significantly better effects for individual or group psychotherapy than for control conditions, further supporting our findings. Nevertheless, the stability of our findings is best determined by additional studies.

Does improvement represent state rather than trait change? This may be true to some degree for self-report measures, for which shorter-term treatments had a larger mean effect size than longer-term treatments. When length of follow-up was controlled, effect size was highly negatively correlated with duration of treatment. This suggests the hypothesis that some of the improvement in self-report outcome may be state-dependent, with the best outcome apparent after a few weeks or months (as evidenced in shorter-term treatments) but later followed by some return to the prior mood state (as evidenced in longer-term treatments). This “honeymoon effect” in the shorter-term treatments was not apparent with observer-rated measures. Nonetheless, the significant difference in self-report outcomes between active therapy and control conditions in randomized, controlled treatment trials indicates that significant change occurred beyond regression toward the mean.

Differential effects by diagnosis

In all studies, individuals with personality disorders did not improve to the same degree as those without personality disorders (9, 12, 13, 15, 21). The NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (27) obtained a similar finding for some measures. Karterud et al. (12) found that patients from the anxious cluster C improved more than patients with borderline personality disorder, who in turn improved more than schizotypal patients. Schizotypal personality disorder appeared to require a longer treatment than the 7 months allotted (12). In his own case series, Stone (34) also noted that schizotypal personality disorder showed more limited improvements than borderline personality disorder. Similarly, Woody et al. (9) found that patients with antisocial personality disorder did not have good outcomes except in the presence of comorbid depression. The association with depression may indicate the ability to form attachments and develop a positive therapeutic alliance (35).

Treatment duration

Among shorter-duration therapies, Alden (10) noted that the changes which patients with avoidant personality disorder made after a 10-week treatment were insufficient to consider them healthy and recommended evaluating longer-duration treatments.

Comparison of the four treatment studies (11, 14, 18, 20) with the five natural history studies (1) suggests a relation between treatment duration and no longer meeting the full criteria for a personality disorder at follow-up. The models in Table 4 estimated that 25% of patients with personality disorders would recover by about 0.4 years, 50% by 1.3 years or 92 sessions, and 75% by 2.2 years or about 216 sessions. Although they are not statistically significant, models 1a and 1b fit the data from the four treatment studies well enough for heuristic purposes. The accuracy of these models is likely to diminish outside the range of the observed data. Thus, for number of sessions (model 1a), recovery is estimable between about 40% and 75% of cases, while for duration of treatment (model 1b), recovery is estimable between about 25% and 75% of cases. Within these ranges the models appear reasonably linear, but the true recovery rates, if known, might vary more toward the extremes. In the shorter time frame, a percentage of patients may appear recovered purely as an artifact of diagnostic error at admission, resulting in false positive cases, or at follow-up, resulting in false negative cases. Some error may be due to state effects, such as acute distress or an axis I episode that biased findings of the admission interview. In a longer time frame, most clinicians know of individuals with treatment-refractory personality disorders who still meet criteria after 5–8 years of treatment. Recovery as a function of time in treatment probably varies with some meaningful patient characteristics. For instance, patients who recover in a shorter time frame may include those with certain cluster C types of disorder, a higher level of functioning, and the abilities to maintain a good therapeutic alliance and to tolerate distressing affects. Finally, the models exclude dropouts, who may in fact be harder to treat, thus biasing the findings and the model toward overestimating recovery.

As shown in Table 4, psychotherapy was associated with about a sevenfold faster rate of recovery than was found in the natural history studies of borderline personality disorder (25.8% versus 3.7% per year). Given similar proportions of attrition in both sets of studies, this difference is not due to dropout bias. The lower proportion of patients with borderline personality disorder (53%) in the four treatment studies may have influenced this comparison, under the likely assumption that cases of borderline personality disorder are harder to treat than the other types, largely cluster C. However, the natural history of borderline personality disorder includes often receiving treatment (1, 5, 36); thus, natural history does not imply lack of treatment. While four studies are insufficient for providing a statistically significant estimate, they do suggest the hypothesis that psychotherapy speeds recovery from a personality disorder—which includes many patients with borderline personality disorder—by a factor of seven over the natural history of borderline personality disorder. This hypothesis is worthy of further validation.

Outcome perspective

Self-report and observer-rated measures demonstrated similar effect sizes at follow-up. However, for self-report measures, larger effects were found among the shorter-term treatments. This confirms our a priori concern that the two measurement perspectives might yield differing results.

The inverse relation between treatment duration and self-report outcomes is paradoxical and intriguing. Cognitive behavior therapy was largely represented among shorter-term treatments (8, 10, 13, 21), with only one longer-term cognitive behavior treatment (parasuicidal patients with borderline personality disorder) (17), which demonstrated one of the lowest self-report effect sizes. Among the longer-term therapies, five (11, 12, 16, 18, 20) were dynamic/interpersonal. Thus, severity and personality disorder type are confounded with therapy type and duration. Cluster C disorders were generally given shorter-duration treatments, usually cognitive behavior therapy. Borderline and other more severe types of personality disorder tended to receive longer-duration treatments, usually dynamic. These data alone cannot resolve the relative contributions of personality disorder type, therapy type, and therapy duration in predicting self-report outcome.

Three possibilities could account for this. The first is that most shorter-duration treatments involved less severely ill patients, who then reported feeling better to a greater degree than did sicker patients treated in longer-term therapy. Another possibility is that longer-duration studies tended to treat patients with borderline and other more severe types of personality disorder who might not have reported as much subjective improvement as cluster C patients, regardless of treatment duration. A third possibility is that observer-rated improvement is more tied to duration of treatment, whereas self-reported improvement is initially highly responsive to treatment in the short term (honeymoon effect), followed by some regression to the mean as longer-term therapeutic work continues. This is consistent with the finding of Kopta et al. (37) that changes in distress and character have different patterns of response over a year of psychotherapy. The interpretation of effect sizes should consider the possibility of a honeymoon effect in the early weeks or months of treatment. Self-report measures may show great response early on but then diminish somewhat, creating a potential bias favoring shorter-term treatments. Use of both measurement perspectives and long-term follow-up should mitigate this problem.

Recommendations

In the examination of these studies, several issues arose repeatedly, which should influence future studies.

1. More studies should examine the differential responses of specific types of personality disorder to specific psychotherapies, since existing data suggest that this is an important phenomenon.

2. In addition to demographic, diagnostic, and severity data, studies should report referral sources and rates of refusal to enter treatment as well as dropout rates. This will help in assessing the generalizability of the findings.

3. Randomized, controlled treatment trials will aid in comparing the effects of specific treatments across types of personality disorder or of treatments for the same type of personality disorder. The use of intent-to-treat analyses, which are used widely in pharmacological trials, should also aid in applying the interpretation of efficacy data to wider considerations of effectiveness.

4. By contrast, the field also needs more naturalistic, observational studies of patients in psychotherapy. As a source of “therapeutic diversity,” these will help us discover effective ingredients not presently in treatment manuals, thereby informing the next generation of treatments.

5. There should be efforts to standardize treatments and/or to describe and measure treatments actually delivered. Randomized, controlled treatment trials usually involve the use of a manual and training seminars followed by group supervision, as well as measurement of therapist competence and adherence to the manual (38). Whenever studies use a naturalistic, observational approach or a treatment-as-usual comparison condition, investigators should assess what treatments were delivered. This may involve interviewing patients about the treatments or assessing taped sessions with the use of standardized measures.

6. Studies should include longer durations of treatment. Most patients with personality disorders do not recover rapidly. Some who do recover rapidly may in fact represent false positive cases. Treatments of less than 1 year’s duration may better be characterized as treating crises, a series of crises, symptoms of distress, or a concurrent axis I disorder rather than core personality disorder psychopathology. Other researchers have drawn similar conclusions. Shea et al. (27) found that at the end of 16 weeks of treatment, subjects with personality disorders had a lower recovery rate from major depression and were more impaired in social functioning than those without personality disorders, findings similar to those of Diguer et al. (15). Kopta et al. (37) demonstrated that characterologic change occurs much later than symptomatic change. Furthermore, characterologic change may actually continue after the end of treatment (delayed effects) (14, 39). It would be useful, for instance, to determine the effective duration (i.e., “dose”) that produces recovery in 25%, 50%, and 75% of individuals with a given personality disorder type. Durations of treatment sufficient to obtain 50% recovery would facilitate detecting which characteristics of patients with personality disorders are highly responsive to treatment, which are responsive but likely to require longer treatment, and which are treatment-resistant and likely to require treatment modifications.

7. Greater uniformity of outcome measures across studies would improve comparison of findings. These should assess several domains of psychopathology and functioning, include observer-rated measures, not focus solely on distress-related symptoms, and include specific problem areas for each disorder. The data in Table 3 suggest that measures vary in their effect sizes following treatment, and therefore reliance on more volatile measures (e.g., target complaints) may impede comparison with studies using measures that are more resistant to change (e.g., social functioning). Studies should also report the percentage of subjects no longer meeting the criteria for a personality disorder at follow-up, using similar measures at intake and follow-up to avoid errors due to poorly comparable methods (4, 28).

8. Studies should include measures of core psychopathology purported to play a causal role in the development and/or maintenance of the disorders (40). Improvement in putative core factors should predict remaining free of personality disorder traits. This should strengthen the links among diagnosis, mechanism of action, and response to treatment, adding to the convergent validation of both disorder and treatment. From a psychodynamic perspective, studies might include the assessment of defense mechanisms, the core conflictual relationship theme, or another dynamic formulation method (41). From a cognitive behavior perspective, studies might assess dysfunctional attitudes, specific schemas, or response to a pathological schema-activation paradigm.

9. Finally, in the spirit of Wilhelm Reich’s early attempts to understand character (42), studies should report data on patients who dropped out or deteriorated with treatment, to discover which treatments are not well tolerated or might adversely affect certain individuals. This involves a certain degree of scientific courage, however, which may require that the researchers be as well analyzed as their treatment findings!

CONCLUSIONS

All 15 studies found significant improvement in patients with personality disorder following psychotherapy. Controlled and naturalistic studies produced findings of similar magnitude, while control treatments or waiting-list conditions, according to data available from three studies, produced less improvement. Four studies found that a mean of 52% of patients recovered—defined as no longer meeting the full criteria for a personality disorder at follow-up—after a mean of 1.3 years of treatment. A heuristic model based on those findings estimated that 25.8% of patients with personality disorder recovered per year of psychotherapy, a rate sevenfold larger than that in a previously published model of recovery in the natural history of borderline personality disorder. While the small number of studies on which these conclusions are based warrants caution, the consistency of the findings suggests that both psychodynamic and cognitive behavior therapies are effective in improving the distress and functioning of individuals with personality disorders. Treatments lasting less than 1 year may be effective for select types, such as some cluster C personality disorders, while the majority of personality disorder types are likely to require longer treatments. More research is needed to confirm and extend these findings.

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of Personality Disorders, Dublin, June 21–24, 1995; the 149th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 4–9, 1996; and the annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Amelia Island, Fla., June 19–23, 1996. Received July 17, 1996; revisions received Feb. 24 and Sept. 28, 1998, and Feb. 22, 1999; accepted March 13, 1999. From the Institute of Community and Family Psychiatry, McGill University; and Harvard Medical School at the Erikson Institute, Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Mass. Address reprint requests to Dr. Perry, Institute of Community and Family Psychiatry, Sir Mortimer B. Davis-Jewish General Hospital, 4333 Chemin de la côte Ste-Catherine, Montreal, Que. H3T 1E4, Canada. The authors thank Andrew C. Leon, Ph.D., for help in considering issues involving calculation of effect sizes.

|

|

|

|

1. Perry JC: Longitudinal studies of personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1993; 7(suppl):63–85Google Scholar

2. Merikangas KR, Weissman MM: Epidemiology of DSM-III axis II personality disorders, in Psychiatry Update: American Psychiatric Association Annual Review, vol 5. Edited by Frances AJ, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1986, pp 258–278Google Scholar

3. Perry JC, Vaillant GE: Personality disorders, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 5th ed, vol 2. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1989, pp 1352–1387Google Scholar

4. Perry JC: Problems and considerations in the valid assessment of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1645–1653Google Scholar

5. Perry JC, Lavori PH, Hoke L: A Markov model for predicting levels of psychiatric service use in borderline and antisocial personality disorders and bipolar type II affective disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1987; 21:215–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Soloff P: Pharmacolgic therapies in borderline personality disorder, in Borderline Personality Disorder: Etiology and Treatment. Edited by Paris J. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992, pp 319–348Google Scholar

7. Fiske DW: Measuring the Concepts of Personality. Chicago, Aldine Press, 1971, pp 68–89Google Scholar

8. Liberman RP, Eckman T: Behavior therapy vs insight-oriented therapy for repeated suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:1126–1130Google Scholar

9. Woody GE, McLellan T, Luborsky LL, O’Brien CP: Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:1081–1086Google Scholar

10. Alden L: Short-term structured treatment for avoidant personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 56:756–764Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Stevenson J, Meares R: An outcome study of psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:358–362Link, Google Scholar

12. Karterud S, Vaglum S, Friis S, Irion T, Johns S, Vaglum P: Day hospital therapeutic community treatment for patients with personality disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:238–243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Fahy TA, Eisler I, Russell GFM: Personality disorder and treatment response in bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:765–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hoglend P: Personality disorders and long-term outcome after brief dynamic psychotherapy. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:168–181Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Diguer L, Barber JP, Luborsky L: Three concomitants: personality disorders, psychiatric severity, and outcome of dynamic psychotherapy of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1246–1248Google Scholar

16. Winston A, Laikin M, Pollack J, Samstag LW, McCullough L, Muran JC: Short-term psychotherapy of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:190–194Link, Google Scholar

17. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1771–1776Google Scholar

18. Monsen JT, Odland T, Eilertsen DE: Personality disorders: changes and stability after intensive psychotherapy focusing on affect consciousness. Psychotherapy Res 1995; 5:33–48Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Monroe-Blum H, Marziali E: A controlled trial of short-term group treatment for borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1995; 9:190–198Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Budman S, Demby A, Soldz S, Merry J: Time-limited group psychotherapy for patients with personality disorders: outcomes and drop-outs. Int J Group Psychother 1996; 46:357–377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hardy GE, Barkham M, Shapiro DA, Stiles WB, Rees A, Reynolds S: Impact of cluster C personality disorders on outcomes of contrasting brief psychotherapies for depression. J Clin Consult Psychol 1995; 63:997–1004Google Scholar

22. Rosenthal RN, Muran JC, Pinsker H, Hellerstein D, Winston A: Interpersonal change in brief supportive psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res 1999; 8:55–63Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

24. Rosenthal R: Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research: Applied Social Research Methods, vol 6. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1991Google Scholar

25. Light RJ, Pillemer DB: Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1984Google Scholar

26. Kazdin AE: Methodology, design, and evaluation in psychotherapy research, in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. Edited by Garfield S, Bergin AE. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, pp 19–71Google Scholar

27. Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin I, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP: Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:711–718Link, Google Scholar

28. Perry JC: Reply to Drs Skodol, Hyler and Oldham: Valid assessment of personality disorders (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1905–1906Google Scholar

29. Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Morey L: Personality disorders assessment: the challenge of construct validity. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:205–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Shea MT: Psychosocial treatment of personality disorders. J Personality Disord 1993; 7(suppl):167–180Google Scholar

31. Luborsky L, Diguer L, Luborsky E, Singer B, Dichter D, Schmidt K: The efficacy of dynamic psychotherapies: is it true that “everyone has won and all must have prizes”? in Psychodynamic Treatment Research: A Handbook for Clinical Practice. Edited by Miller N, Luborsky L, Barber JP, Docherty JP. New York, Basic Books, 1993, pp 497–516Google Scholar

32. Petitti DB: Meta-Analysis, Decision Analysis and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Methods for Quantitative Synthesis in Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

33. Piper WE, Rosie JS, Azim HFA, Joyce AS: A randomized trial of psychiatric day treatment for patients with affective and personality disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:757–763Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Stone MH: Psychotherapy with schizotypal borderline patients. J Am Acad Psychoanal 1983; 11:87–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Gerstley L, McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Woody GE, Luborsky L, Prout M: Ability to form an alliance with the therapist: a possible marker of prognosis for patients with antisocial personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:508–512Link, Google Scholar

36. Skodol AE, Buckley P, Charles E: Is there a characteristic pattern to the treatment history of clinic outpatients with borderline personality? J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:405–410Google Scholar

37. Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, Beutler LE: Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:1009–1016Google Scholar

38. Barber JP, Crits-Christoph P, Luborsky L: Effects of therapist adherence and competence on patient outcome in brief dynamic therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:619–622Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Crits-Christoph P: The efficacy of brief dynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:151–158Link, Google Scholar

40. Perry JC: Challenges in validating personality disorders: beyond description. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:273–289Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Perry JC: Scientific progress in psychodynamic formulation. Psychiatry 1989; 52:245–249Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Reich W: Character Analysis, 3rd ed. New York, Simon & Shuster, 1949Google Scholar