A Survey of New Yorkers After the Sept. 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms among residents/workers in Manhattan 3–6 months after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. METHOD: A total of 1,009 adults (516 men and 493 women) were interviewed in person throughout Manhattan. All answered questions about themselves before and after September 11 that included their emotional status. RESULTS: A total of 56.3% had at least one severe or two or more mild to moderate symptoms. Women reported significantly more symptoms than men. Loss of employment, residence, or family/friends correlated with greater and more severe symptoms. The most distressing experiences appeared to be painful memories and reminders; dissociation was rare. Only 26.7% of individuals with severe symptoms were obtaining treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Over half of the individuals had some emotional sequelae 3–6 months after September 11, but the percent was decreasing. Only a small portion of those with severe responses was seeking treatment.

On Sept. 11, 2001, terrorists crashed two major airliners into the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, causing both of its towers to collapse within a short period of time. Two additional planes were hijacked, one crashing into the Pentagon and the other over a Pennsylvania field. Approximately 3,000 individuals were killed. The events of this one morning left much of the world in a state of mass emotional shock and in particular left the United States and even more so New York City in a state of panic about the daily safety of all citizens and dread about what could occur next. Since most victims of this disaster were killed, it was quickly realized that the main medical response needed in its aftermath was psychiatric. Teams of psychiatrists were thus mobilized (1), and centers for counseling were established to serve all displaced survivors and the families of deceased victims.

There has been only one disaster of greater magnitude in the United States (i.e., with respect to the number of civilian deaths), the Galveston hurricane of 1900, in which more than 6,000 were killed. Certainly the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City, the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, and several natural disasters such as floods and fires left many people homeless and/or unemployed. Several reports of the psychiatric consequences of these kinds of events exist (1–7), and they suggest that early detection and treatment may prevent long-term disability from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or chronic anxiety and depression. The events of September 11 were unusual in that most people could not avoid being affected in some way, since television news, the Internet, and newspapers were filled with repetitive pictures of the mass destruction of lower Manhattan, fumes and odors were present throughout much of Manhattan, smoke was visible from ground zero for many weeks afterward, and police and the National Guard were densely posted throughout the city. We thus felt it important for the future planning of psychiatric services throughout New York City and its suburbs to assess the psychiatric well-being of a representative cohort of those who live or work in Manhattan. The following describes interviews of over 1,000 New Yorkers 3 to 6 months later.

Method

In-person interviews of people in New York City were conducted from Dec. 15, 2001, until Feb. 28, 2002. Manhattan was subdivided into seven regions: lower (within the vicinity of ground zero), Greenwich Village to 14th Street, 14th to 30th Streets, 31st to 59th Streets, West 60th to 100th Streets, East 60th to 100th Streets, and Washington Heights (northern Manhattan). Indoor public sites with space for semiprivate interviews were used. These included public libraries, motor vehicle bureaus, cafes, and commuter train and ferry stations. Interviews were conducted from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. or later in the evening 7 days a week in order to survey both employed and unemployed individuals. Selection of subjects was based on sex, age, and ethnic and racial groups to provide a representative sample of New Yorkers similar to the distribution reported in the 2000 New York City census (8, 9).

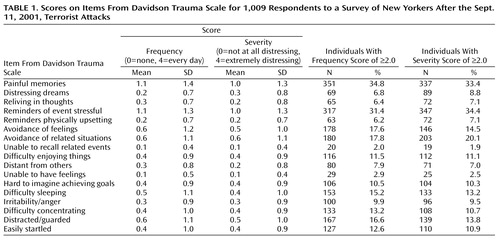

Interviewers who had prior experience working in clinical psychiatry were trained by one of the authors (L.E.D.) to perform structured interviews that included questions about demographics, personal losses and exposure to the event, and medical, psychiatric, and medication histories of each individual before Sept. 11, 2001, and a similar history for the time after September 11 until the day of the interview. The Davidson Trauma Scale (10) was used to detect the presence, frequency, and severity of symptoms that are characteristic of individuals who develop PTSD (11) (Table 1). Each of the 17 items on the Davidson Trauma Scale was scored from 0 to 4 for both frequency (0=none to 4=every day) and severity within the past week (0=not at all distressing to 4=extremely distressing). A total score is obtained by adding the frequency and severity scores for each item (range=0–136). Three subscales were defined by using this scale (10, 11): intrusion, avoidance/numbing, and hyperarousal. The intrusion score is calculated as the cumulative score of frequency and severity scores for five questions relating to this category, the avoidance/numbing score as the cumulative score for six corresponding questions, and the hyperarousal score as the cumulative score for four corresponding questions. A score of 8.0 on any one item is considered the highest level of pathology, while a score of 0.0 means that the item is not present. On the basis of previous studies (10), 82.1% of the individuals with diagnosed DSM-IV PTSD reported a score of 24 or higher on the Davidson Trauma Scale; thus, 24 is considered by Davidson to be a cutoff for an approximate 4 to 1 likelihood that an individual has PTSD. Davidson reported high test-retest reliability for this scale within a 1-week period (r=0.86, p<0.0001), and its validity was shown by high correlation with other similar scales (10).

The amount of direct exposure to the event was assessed by quantifying the involvement of the individual’s experience (from evacuation from the World Trade Center, to watching the events from a distance, to watching the events on television, to not even seeing the events on television). The impact of the events was similarly quantified personally and professionally (i.e., loss of a relative or employment). Alcohol consumption was addressed and quantified by number of drinks per week.

The institutional review boards of both New York University Medical Center and Mount Sinai Medical Center approved this study. The subjects were approached and explained the nature of the study; those willing to complete the interview gave written informed consent for participation. The interviews were performed and coded to mask each individual’s identity and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

The data were analyzed by using SPSS, Version 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago). Standard frequency distributions for each symptom and syndrome were calculated. Analyses of covariance (with items from the Davidson Trauma Scale as dependent variables, demographic characteristics as independent variables, and sex and age as covariates) were used to detect differences between the individuals who were or were not previously in psychiatric treatment. Pearson’s correlations were used to determine associations between variables.

Results

Of the 1,779 individuals approached, a total of 1,009 adults (56.7%) completed the interview. These were 516 men and 493 women (mean age=36.0 years, SD=13.4, range=18–85). A total of 850 (84.2%) of the interviewees either worked or lived in Manhattan at the time of the attacks. A total of 58.1% were Caucasian; the remainder were African American (21.3%), Hispanic (10.4%), or “miscellaneous other” (10.2%). A total of 5.3% were unemployed, 12.7% were unskilled workers, 34.1% were skilled workers, 30.4% were professionals/executives, 12.1% were students, and 5.1% were “other.” Of those who refused to participate, 47.2% were men, 52.7% were women, and 51.5% were Caucasian.

A total of 28.9% (N=292) of those interviewed had their employment changed in some way by the disaster (e.g., they lost a job, lost time from work, or had hours or responsibilities reduced or changed). A total of 10.5% (N=106) lost a close family member and/or friend, although 72.3% (N=730) did not know of anyone who died as a result of the event. A total of 4.8% (N=48) lost their place of residence.

The most frequent symptoms appearing in approximately one-third of the group were recurring painful memories and discomfort while experiencing reminders of the event (Table 1). For all individuals, the mean total score on the Davidson Trauma Scale was 14.3 (SD=16.7); the mean intrusion score was 5.6 (SD=6.4), the mean avoidance/numbing score was 4.6 (SD=6.5), and the mean hyperarousal score was 4.2 (SD=7.0). The mean total score for the men was 11.7 (SD=13.8); for the women, it was 17.0 (SD=18.8). The women reported significantly more total symptoms than the men (F=26.0, df=1, 1007, p<0.001), and this was true for all three syndromes.

The 63 individuals who were in previous psychiatric treatment had significantly greater mean scores on the Davidson Trauma Scale (total: F=15.3, df=1, 994, p<0.0001; intrusion: F=11.5, df=1, 994, p<0.001; hyperarousal: F=13.3, df=1, 994, p<0.0001; and avoidance/numbing: F=7.2, df=1, 994, p<0.007) than those who reported no prior treatment.

A total of 56.3% of all subjects (N=568) (21.7% of the men [N=112] and 62.3% of the women [N=307]) had total scores higher than 8.0 (representing at least one very severe symptom or two or more mild to moderate symptoms). A total of 11.3% of the subjects (N=114) reported that they were currently receiving psychotherapy or other trauma- or grief-related counseling that began after September 11. Only 7.7% (N=78) obtained treatment independently, while 3.6% (N=36) obtained treatment at their job (either voluntarily or as required). A total of 1.4% (N=14) were receiving psychotropic medications. A total of 18.5% of the individuals (69 men and 118 women) had Davidson Trauma Scale scores higher than 24.0. Of these, only 26.7% (N=269) reported that they were receiving any kind of treatment.

The higher the Davidson Trauma Scale score, the closer one’s residence was to the disaster (r=–0.14, p<0.01). Similarly, the greater the direct exposure to the event, the higher the current Davidson Trauma Scale score (r=0.22, p<0.001), and the greater the occupational disturbance, the higher the Davidson Trauma Scale score (r=0.20, p<0.01). The greater the time from September 11 until the interview, the less the psychopathology seen (total score on the Davidson Trauma Scale: r=–0.19, p<0.01; intrusion score: r=–0.19, p<0.01; avoidance/numbing score: r=–0.16, p<0.01; hyperarousal score: r=–0.14, p<0.01).

Surprisingly few individuals reported an increase in alcohol consumption as a result of the September 11 events (6.8%, N=69), and very few of those interviewed admitted to the use of any “street drugs” before or after September 11 (4.8% [N=48] before and 4.0% [N=40] afterward). There was no statistically significant increase in any medication intake after September 11.

Discussion

A total of 1,009 individuals were interviewed in Manhattan about how they were coping after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. A total of 56.3% individuals had some evidence of residual emotional distress 3–6 months later, the amount of which (consistent with previous literature [5–7, 12–18]) was correlated with having a preexisting psychiatric disorder, having great direct exposure to the traumatic event, and being a woman. The form of this distress was most commonly painful memories and anxiety when reminders occurred, rather than signs of avoidance and numbness. Although it might have been expected that alcohol and drug use would increase as a consequence of the terrorist attacks (4), we failed to find this to be true.

There have been two previous surveys published about the prevalence of emotional stress in New York City and nationally as a consequence of the events of Sept. 11, 2001 (19, 20), and more are likely to come. Both of these were conducted earlier than the present study and relied on random telephone interviews. Despite the differences in methodology of these studies, the rate of detected symptoms in the present study is similar and even somewhat higher than that in reference 20.

Our results surprisingly show that very few of those interviewed (11.3%) received any psychiatric help or took medications for anxiety, depression, or psychotic conditions despite the city-wide escalation in psychiatric services. Of those people (18.5% of the total) considered to have enough symptoms to put them at risk for PTSD, only 26.7% were receiving counseling or psychiatric treatment. Thus, it appears that even in New York City, where psychiatrists and other mental health professionals are in large abundance, those who could be in need of treatment may still not be adequately pursuing it. Nevertheless, those with severe symptoms were far fewer than what we expected, given the magnitude and amount of personal exposure to this disastrous event.

|

Received April 10, 2002; revisions received July 11 and Aug. 20, 2002; accepted Oct. 12, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, New York University; Disaster Psychiatry Outreach, Inc., New York; and Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. DeLisi, Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Department of Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, 650 First Ave., Fifth Floor, New York, NY 10016; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by Disaster Psychiatry Outreach, Inc., a nonprofit organization providing psychiatric care to victims of disasters. Dr. Adam Turner and Shannon MacDonald contributed to the initial planning of the research protocols.

1. Lagnatto L: Disaster psychiatry volunteers minister to the distraught. Wall Street Journal, Sept 14, 2001, p B19Google Scholar

2. Dew MA, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC, Dunn LO, Parkinson DK: Mental health effects of the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor restart. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1074-1077Link, Google Scholar

3. North CS: The course of post-traumatic stress disorder after the Oklahoma City bombing. Mil Med 2001; 166(suppl 12):51-52Google Scholar

4. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755-762Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Green BL, Lindy JD: Post-traumatic stress disorder in victims of disasters. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1994; 17:301-309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, Najarian LM, Fairbanks LA, Tashjian M, Pynoos RS: Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:911-916Link, Google Scholar

7. Katz CL, Pellegrino L, Pandya A, Ng A, DeLisi LE: Research on psychiatric outcomes and interventions subsequent to disasters: a review of the literature. Psychiatry Res 2002; 110:201-217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Table 5 Population by Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin, for the 15 Largest Counties and Incorporated Places in New York:2000. http://www.census.gov/census2000/states/ny.htmlGoogle Scholar

9. New York City Department of City Planning. http://www.ci.nyc.ny.us/html/dcp/html/census/popdiv.htmlGoogle Scholar

10. Davidson J: Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS). North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems, 2003Google Scholar

11. Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R, Feldman ME: Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 1997; 27:153-160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Carr VJ, Lewin TJ, Webster RA, Kenardy JA, Hazell PL, Carter GL: Psychosocial sequelae of the 1989 Newcastle Earthquake, II: exposure and morbidity profiles during the first 2 years post-disaster. Psychol Med 1997; 27:167-178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Shore JH, Tatum EL, Vollmer WM: Psychiatric reactions to disaster: the Mount St Helens experience. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:590-595Link, Google Scholar

14. Yehuda R: Current concepts: post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:108-114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Helzer JE, Robin LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630-1634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Rosenberg SD: Premilitary MMPI scores as predictors of combat-related PTSD symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:479-483Link, Google Scholar

17. Smith EM, North CS, McCool RE, Shea JM: Acute postdisaster psychiatric disorders: identification of persons at risk. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:202-206Link, Google Scholar

18. Zlotnick C, Zimmerman M, Wolfsdorf BA, Mattia JI: Gender differences in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder in a general psychiatric practice. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1923-1925Link, Google Scholar

19. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliot MN, Zhou AJ, Kanouse DE, Morrison JL, Berry SH: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1507-1512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sandro G, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:982-987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar