Suicide Risk in Relation to Socioeconomic, Demographic, Psychiatric, and Familial Factors: A National Register–Based Study of All Suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Suicide risk was addressed in relation to the joint effect of factors regarding family structure, socioeconomics, demographics, mental illness, and family history of suicide and mental illness, as well as gender differences in risk factors. METHOD: Data were drawn from four national Danish longitudinal registers. Subjects were all 21,169 persons who committed suicide in 1981–1997 and 423,128 live comparison subjects matched for age, gender, and calendar time of suicide by using a nested case-control design. The effect of risk factors was estimated through conditional logistic regression. The interaction of gender with the risk factors was examined by using the log likelihood ratio test. The population attributable risk was calculated. RESULTS: Of the risk factors examined in the study, a history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorder was associated with the highest odds ratio and the highest attributable risk for suicide. Cohabiting or single marital status, unemployment, low income, retirement, disability, sickness-related absence from work, and a family history of suicide and/or psychiatric disorders were also significant risk factors for suicide. Moreover, these factors had different effects in male and female subjects. A psychiatric disorder was more likely to increase suicide risk in female than in male subjects. Being single was associated with higher suicide risk in male subjects, and having a young child with lower suicide risk in female subjects. Unemployment and low income had stronger effects on suicide in male subjects. Living in an urban area was associated with higher suicide risk in female subjects and a lower risk in male subjects. A family history of suicide raised suicide risk slightly more in female than in male subjects. CONCLUSIONS: Suicide risk is strongly associated with mental illness, unemployment, low income, marital status, and family history of suicide. The effect of most risk factors differs significantly by gender.

A better understanding of risk factors for suicide as well as of the magnitude of the effect of known risk factors in the general population is crucial for the design of suicide prevention programs. Suicide risk in the general population has been reported to be associated with male gender (1), single marital status (2, 3), unemployment (4, 5), lower social class (6), substance abuse (7), physical illness (6, 8), and psychiatric disorders (1, 9, 10). However, the relative importance and the magnitude of these effects, as well as gender differences in these effects, are poorly understood. On the basis of a 5% sample of suicides in Denmark, we previously estimated suicide risk in relation to a wide range of socioeconomic factors and mental illness (11, 12). However, those reports might have underestimated the effect of socioeconomic factors because the data for those variables were based on records from a period 2 years before the time of the suicide. In addition, statistical power in those studies was not sufficient to examine some less common factors associated with suicide risk. Several other findings for suicide risk factors have not been examined in detail. Suicidal behavior has been found to cluster in families (13, 14), but it remains unclear to what extent this can be explained by the familial clustering of psychiatric disorders and other factors. Also, suicide mortality rates are generally higher in urban than in rural areas in many countries (15), but very little research has addressed the effect of urbanization in the context of other individual factors. In addition, parenthood has been suggested to be protective against suicide (16, 17), but very few empirical studies of this relationship have been done (18).

In this study, we used data for the total national sample of cases of suicide in Denmark over a 17-year period to 1) investigate the joint effect on the risk of suicide in the general population of a large range of factors regarding family structure, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, mental illness, and family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders; 2) examine gender differences in risk factors for suicide; and 3) estimate the population attributable risk associated with identified risk factors for suicide in order to evaluate their influence on the population level.

Method

Data Sources

This study was based on data from four Danish longitudinal registers. The Cause-of-Death Register, part of the Danish Medical Registers on Vital Statistics (19), includes records on the cause and date of all deaths in Denmark and has been computerized since 1969. Suicide was coded in the register with the ICD-8 codes E950–E959 during 1969–1993 and the ICD-10 codes X60–X84 since 1994. The Danish Psychiatric Central Register (20), which has been computerized since 1969, covers all psychiatric inpatient facilities in Denmark and cumulatively records admission and discharge data, including dates and main and auxiliary diagnoses. The IDA Database (21), a Danish acronym for the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research, contains longitudinal annual information on labor market conditions and sociodemographic information for all individuals living in Denmark. The Danish Civil Registration System (22) contains a personal identifier for all individuals residing in Denmark and includes links to their parents. By using these links, the first-degree relatives (i.e., children, father, mother, and siblings, through links to father and mother) of an individual listed in the Danish Civil Registration System can be identified. A large proportion of the population, however, has no registered links to their first-degree relatives because 1) the person was not living with a parent/child in the year 1969, 2) the parent/child died before the year 1969, 3) the parent/child emigrated from Denmark before the year 1979, or 4) the person immigrated to Denmark as an adult. In practice, these selection mechanisms mean that a link to at least the mother is available for almost everybody born in Denmark during or after 1960, with the proportion of persons with a link to the mother gradually decreasing with birth year to about 50% of those born in 1952. For persons born before 1952, it is rarely possible to establish links to parents or siblings.

The unique personal identifier in the Danish Civil Registration System (22) for each subject was used as a key to retrieve and merge individual information from different databases. Approval for the study was obtained from the Danish Data Protecting Agency.

Subjects

Suicide cases were identified in the Cause-of-Death Register with a restriction that the person who committed suicide was residing in Denmark during the year before the year of the suicide and thus had complete socioeconomic information in the IDA Database for that previous year. A total of 21,169 cases of suicide were selected for the period from January 1, 1981, to December 31, 1997, which accounted for 99.64% of all suicides for this 17-year period in Denmark.

Comparison subjects were drawn from a 5% random sample of the total population in the IDA database by using a nested case-control design (23), matching for age, gender, and calendar time of the suicide (i.e., each person who committed suicide was matched with an individual who was alive and observed in the 5% sample of population in the IDA Database on the date of suicide and who had the same gender and birth year as the person who committed suicide). If more than 20 eligible comparison subjects were available for one person who committed suicide, then 20 comparison subjects were randomly chosen from that group. Otherwise, all eligible comparison subjects were selected. This procedure was followed for each suicide, resulting in a sample of 423,128 matched comparison subjects matched for the total of 21,169 persons who committed suicide. In only a few cases of suicide involving persons older than age 93 years was it not possible to find 20 comparison subjects.

Variables

Variables included in this study were chosen on the basis of the results of our preliminary analyses and previous studies. Socioeconomic and demographic information for each subject was extracted from IDA Database records for the 1 year before the year of the matching time. The marital status categories were married, cohabiting (defined by Statistics Denmark as living at the same address with a partner of opposite sex and <15 years’ difference in age), or single. Registered partners (i.e., homosexual couples living under the same legal status as a married couple) could be distinguished from single persons only from 1994 onward. Other categories for family structure included parenthood status (parent of a child <2 years old, 2–3 years old, 4–6 years old, or no young child, according to the age of the youngest child). Labor market status was classified into nine mutually independent categories, including fully employed, <20% degree of unemployment, 20%–80% degree of unemployment, >80% degree of unemployment, age pensioner (indicating retirement after age 60), disability pensioner (indicating retirement owing to permanent disability before age 60), receipt of other social benefits, out of labor market (receiving no social benefits), and full-time student. The degree of unemployment was measured by the proportion of weeks in the year for which unemployment benefits were paid. Annual gross income and wealth (property or debt) were divided into four quartiles on the basis of the 5-year age-group-specific distribution in the general population in the calendar year. Place of residence was classified according to the degree of urbanicity by using three categories: the capital area (the Copenhagen and Frederiksberg municipality and its suburbs), cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, and other areas. Ethnicity was grouped according to the subject’s citizenship and place of birth as follows: Danish citizens born in Denmark, Danish citizens born in Greenland, Danish citizens born abroad, and non-Danish citizens. Presence of a sickness-related absence from work (i.e., absence for more than 3 consecutive weeks due to illness) was noted.

Data on psychiatric hospitalization history were derived from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register and updated to the specific matching time. Psychiatric hospitalization history was classified as never admitted, currently admitted, and 1–7 days, 8–30 days, 1–6 months, 7–12 months, or >1 year since the date of the latest discharge.

To gain access to data on family history of psychiatric disorder and suicide, we first identified the first-degree relatives of study subjects from the Danish Civil Registration System, then merged their personal identifiers with the Danish Psychiatric Central Register and the Cause-of-Death Register to see whether the relatives were represented in those databases. In this study, a record of family suicide history meant that at least one relative died from suicide during the period from January 1, 1970, to the matching time. A record of family psychiatric history meant that at least one relative had been hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder some time during the period from April 1, 1969, to the matching time.

Statistical Method

Descriptive analyses were carried out by using SAS. The effects of study variables were examined with conditional logistic regression by using the PhReg procedure in SAS release 6.12 (24), which yielded Wald chi-square test values, odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The full model of joint analysis could not be replaced by a reduced model. The p value for the interaction between gender and a specific variable was based on the likelihood ratio test by comparing the likelihood value of the full model, including all variables and gender interactions with each category of all variables, with the likelihood value of the same model excluding only the gender interactions with each category of the specific variable. The population attributable risk was calculated as described by Bruzzi et al. (25) on the basis of adjusted relative risks from the joint analysis and the distribution of exposure among the subjects who committed suicide. The asymptotic 95% CIs were calculated by using the delta method (26).

Results

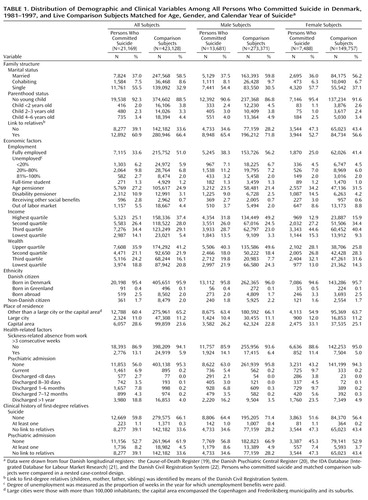

Of the total of 21,169 persons who committed suicide, 35.4% (N=7,488) were female and 64.6% (N=13,681) were male. Their ages ranged from 9 to 103 years, with a mean of 52.1 years (SD=17.7) (50.6 years [SD=18.0] for the male subjects and 55.0 years [SD=16.9] for the female subjects). Table 1 shows the distribution of the study variable categories among the male and female subjects who committed suicide and their comparison subjects.

Risk Factors for Suicide

The results of a conditional logistic regression analysis examining risk factors for suicide are shown in Table 2. For all subjects, the crude odds ratios associated with each factor reflected expected effects, on the basis of previous findings. However, when all variables were included in the full model and adjusted for the each others’ effects, the effect of each factor changed because of the interactions and confounding. A psychiatric disorder leading to hospitalization was the most prominent risk factor for suicide, and risk was extremely high for those recently discharged from the hospital. Both a family suicide history and a family psychiatric history significantly increased suicide risk. Those who were single or cohabiting had a higher suicide risk than those who were married. The protective effect of having young children was significant only for parents of a child less than 2 years old. Urbanization was not a risk factor for suicide after the effects of all other factors were controlled. Danish citizens born in Greenland or other countries had a higher risk of suicide, and non-Danish citizens had a lower risk, compared with citizens born in Denmark. The effect of a low level of wealth was reversed in the joint analysis. However, the effect of unemployment remained significant, and the odds ratios clearly increased with the degree of unemployment. Also, the risk was significantly higher for those in the lowest income quartile.

In addition, registered partners included as a separate category in the analysis had an odds ratio of 4.31 (95% CI=2.23–8.36) in the crude analysis and 3.63 (95% CI=1.71–7.67) in analyses with adjustment for other factors in the full model.

Gender Differences in Risk Factors

The results of gender interaction tests and separate joint analyses for male and female subjects indicated that the general effects of the risk factors reflected different effects in male and female subjects (Table 2). Although many risk factors were significant for both genders, the effect size and even the direction of many factors differed prominently by gender. A psychiatric history had a stronger effect on suicide risk in female than in male subjects, and a family suicide history raised suicide risk slightly more in female than in male subjects. Suicide risk increased with the degree of unemployment in male subjects but not in female subjects. Compared to both high and low income, a middle-level income markedly reduced suicide risk in female but not in male subjects. Being a non-Danish citizen was associated with a significantly lower risk of suicide in male subjects, whereas being a foreign-born Dane was a significant risk factor only for female subjects. Moreover, suicide risk was reduced for male subjects residing in more urbanized areas, whereas the opposite was the case for female subjects. In addition, the protective effect of parenthood for male subjects was significant only for those with a child <2 years old, whereas the protective effect remained significant for female subjects with a child up to 6 years old.

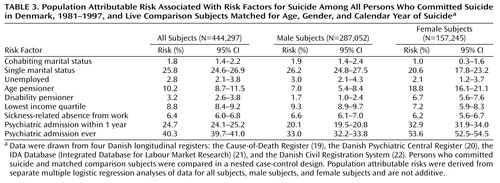

Population Attributable Risk

Table 3 presents the population attributable risk associated with the risk factors that were identified as important in terms of effect size and exposure level in the general population. The factor with the highest attributable risk was a psychiatric disorder leading to hospitalization, followed by being single and being retired (age pensioner).

Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

Data in Danish registers are collected systematically and uniformly and without the purpose of being used for specific research. Use of such data may reduce the risk of differential misclassification bias. On the other hand, the selection of variables that can be included in the analysis is largely dependent on the availability of data in source registers, making some variables of interest, e.g., previous suicide attempts, absent in this study. Also, information on psychiatric illness not leading to hospitalization was not included in the register before the year 1995, which might result in an underestimate of mental illness in the analyses presented here. Nevertheless, because this study used data retrieved from Danish longitudinal registers, it is, to our knowledge, the largest case-control study in suicide research in terms of both the number of suicides and the number of variables included in the analysis. The large number of suicides yielded good statistical power for the study of relatively uncommon risk factors, and the large number of variables allowed estimation of the relative importance of a range of factors associated with suicide.

Findings and Explanations

This study demonstrates that a history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorder was the strongest risk factor for suicide in terms of both effect size and attributable risk in the general population in Denmark and that this risk factor increased suicide risk significantly more in female than in male subjects. These findings are highly consistent with our previous reports (11, 12) and also in line with the literature (9, 27, 28), although our estimates of suicide risk are likely to be low. Also, the finding of a high risk of suicide for people with disability or a sickness-related absence from work is concordant with other reports (6, 8). The obvious decrease in the odds ratios associated with disability and sickness-related absence from work in the joint analysis, compared with the crude analysis, might be explained by the strong association between these two variables and mental illness.

The findings regarding the effect of labor market status, income, and wealth on suicide (with adjustment only for age and gender) are compatible with other reports (4, 5). However, the fact that the odds ratios for these variables decreased markedly or even reversed with further adjustment for other factors suggests that the effects of socioeconomic factors on suicide tend to be overestimated when the distribution of psychiatric disorders is not taken into account. Our results showing that economic stressors such as unemployment and low income increase suicide risk more in male than in female subjects are in line with the results of our previous study (12) and support the hypothesis that men respond more strongly to poor economic conditions than women do (29).

As for family structure, previous studies have reported that single people are more likely to commit suicide (2, 3), but our study further shows a significantly higher risk of suicide for cohabiting people even though cohabitation is almost equivalent to an officially certified marriage relationship in the eyes of most people in Denmark. Moreover, consistent with a few studies reporting that same-gender sexual orientation is associated with suicidality (30, 31), our results clearly show an elevated suicide risk for homosexuals, although this effect was likely to be underestimated because data were available only for those choosing to officially register as partners and only for the period after 1994. Taken together, our results suggest that a traditional family structure may be associated with lower suicide risk, although we cannot determine if the lower risk results from a protective effect of marriage, e.g., in the face of setbacks or difficulties, or from a marriage selection effect (32). In addition, our findings of gender differences in relation to the effects of marital status and parenthood on suicide risk support the hypothesis first suggested by Durkheim (17) that the protective effect of marriage for women is largely an effect of being a parent. This hypothesis is also concordant with the so-called attachment effect suggested by Adam (16). In our study, being a parent of a young child, rather than being married per se, appeared to explain the apparent protective effect of marriage for women, whereas marriage appeared to be a protective factor in its own right for men (33).

With regard to demographic factors, this study shows that living in urban areas, in the context of other factors, increased suicide risk in female subjects but reduced the risk in male subjects. This difference might be explained by aspects of living in a big city that affect men and women differently, e.g., better job opportunities may be more likely to benefit men, whereas women may be more vulnerable in a competitive environment than their male counterparts. The high risk of suicide for Danish citizens born in Greenland may be explained by the Greenlandic cultural tradition of seeing suicide as an acceptable solution for problems rather than as a mortal sin (34). The finding of a high risk of suicide for foreign-born Danes is consistent with a Swedish study by Johansson et al. (6), but this effect was prominent only for female subjects, after other factors were adjusted. Meanwhile, this study showed that male non-Danish citizens had a lower risk of suicide, perhaps due to racial differences in suicide risk (35) and/or cultural differences in attitudes toward suicidal behavior. Denmark has relatively few immigrants, with female immigrants often coming from Western European and other Nordic countries where suicide rates in women are generally high, and male immigrants, especially those with a non-Danish citizenship, coming from a broader spectrum of countries. The fact that a relatively large proportion of male immigrants come from Islamic countries where suicide rates traditionally are low may also contribute to our findings. Another explanation may be that female immigrants to Denmark often come for the purpose of marriage rather than work or business, and thus they may have fewer contacts with other people, may be more isolated from the society, may be less independent, and may experience more stressors, compared to male immigrants.

The familial clustering of suicidal behaviors and psychiatric disorders has been demonstrated in studies of both adolescent and adult suicide victims and attempters (14, 36, 37). Our study further shows that the two familial factors raise the risk of suicide even after the effects of the person’s own psychiatric admission status and other factors are adjusted, although this finding may apply only to relatively young subjects because older people in this study rarely had registered links to their relatives. Since people with a psychiatric disorder are more likely to commit suicide (28), one could argue that liability for suicidal behavior is familially transmitted as a trait dependent on psychiatric disorder. However, our findings suggest that it is less likely that family clustering of suicidal behavior is due only to familial transmission of mental illness. We address this issue elsewhere (38). In addition, the slightly stronger influence of family suicide history in women might be explained by gender differences in reactions toward bereavement (39).

Research and Clinical Implications

The socioeconomic environment in Denmark is similar to that in other Scandinavian countries and would probably also be comparable to that in most Western European countries. However, it may be difficult to generalize the findings of this study to other countries with different social, economic, or cultural conditions. Nevertheless, this large record linkage study has demonstrated the joint effect of a wide range of factors on suicide risk. The results suggest several factors that may be targeted in suicide prevention programs; at the same time they suggest that the effects may differ in various segments of population, e.g., by gender.

We believe, as also suggested by others (11, 40), that mental illness should be a focus for preventive interventions and assessment of these interventions. General strategies with the potential of reducing suicide rates include providing psychiatric professionals and general practitioners with better training in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, as well as continuing psychiatric patients’ care beyond the point of clinical recovery. Also, broader approaches such as reducing unemployment and improving social cohesion might have some, although probably limited, effect on suicide rates.

|

|

|

Received Dec. 6, 2001; revision received July 16, 2002; accepted Oct. 8, 2002. From the National Center for Register-Based Research, Aarhus University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Qin, National Center for Register-Based Research, Aarhus University, Taasingegade 1, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Danish Research Council, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and the Danish National Research Foundation. The authors thank Prof. Niels Westgaard-Nielsen and Prof. Tor Eriksson of the Center for Labour Market and Social Science Research at Aarhus University for their helpful suggestions.

1. Lawrence DM, Holman CD, Jablensky AV, Fuller SA: Suicide rates in psychiatric in-patients: an application of record linkage to mental health research. Aust NZ J Public Health 1999; 23:468-470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kposowa AJ: Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54:254-261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK: Social factors in suicide. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:747-753Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lewis G, Sloggett A: Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment: record linkage study. Br Med J 1998; 317:1283-1286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johansson SE, Sundquist J: Unemployment is an important risk factor for suicide in contemporary Sweden: an 11-year follow-up study of a cross-sectional sample of 37,789 people. Public Health 1997; 111:41-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Johansson LM, Sundquist J, Johansson SE, Bergman B: Ethnicity, social factors, illness and suicide: a follow-up study of a random sample of the Swedish population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:125-131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Murphy GE: Psychiatric aspects of suicidal behaviour: substance abuse, in The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Edited by Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2000, pp 135-146Google Scholar

8. Stenager EN, Madsen C, Stenager E, Boldsen J: Suicide in patients with stroke: epidemiological study. Br Med J 1998; 316:1206-1210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Baxter D, Appleby L: Case register study of suicide risk in mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 175:322-326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Goldacre M, Seagroatt V, Hawton K: Suicide after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care. Lancet 1993; 342:283-286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Erikson T, Qin P, Westergaard-Nielsen N: Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet 2000; 355:9-12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Qin P, Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Westergard-Nielsen N, Eriksson T: Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:546-550Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Roy A, Nielsen D, Rylander G, Sarchiapone M: The genetics of suicidal behaviour, in The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Edited by Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2000, pp 209-221Google Scholar

14. Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Liotus L, Schweers J, Balach L, Roth C: Familial risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:52-58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. World Health Organization: World Health Statistics Annual. Geneva, WHO, 1989Google Scholar

16. Adam KS: Environmental, psychosocial, and psychoanalytic aspects of suicidal behavior, in Suicide Over the Life Cycle: Risk Factors, Assessment, and Treatment of Suicidal Patients. Edited by Blumenthal SJ, Kupfer DJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 39-96Google Scholar

17. Durkheim E: Suicide. Translated by Spaulding JA, Simpson G. New York, Free Press, 1966Google Scholar

18. Hoyer G, Lund E: Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:134-137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Sundhedsstyrelsen [The Danish National Board]: Dødsårsagerne 1991 [Cause of Death in Denmark 1991]. Copenhagen, Danish National Board, 1993Google Scholar

20. Munk-Jorgensen P, Mortensen PB: The Danish Psychiatric Central Register. Dan Med Bull 1997; 44:82-84Medline, Google Scholar

21. Danmarks Statistik: IDA—en integreret database for arbejdsmarkedsforskning. Copenhagen, Danmarks Statistiks trykkeri, 1991Google Scholar

22. Malig C: The Civil Registration System in Denmark: Technical Papers of the International Institute for Vital Registration and Statistics, vol 66. Bethesda, Md, IIVRS, 1996Google Scholar

23. Clayton D, Hills M: Statistical Models in Epidemiology. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

24. SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements Through Release 6.12, Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1997Google Scholar

25. Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Schairer C: Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol 1985; 122:904-914Medline, Google Scholar

26. Agresti A: Categorical Data Analysis. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1990Google Scholar

27. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann JH, Forbes NT, Caine ED: Relationships of age and axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1001-1008Link, Google Scholar

28. Harris EC, Barraclough B: Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:205-228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Crombie IK: Can changes in the unemployment rates explain the recent changes in suicide rates in developed countries? Int J Epidemiol 1990; 19:412-416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bagley C, D’Augelli AR: Suicidal behaviour in gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Br Med J 2000; 320:1617-1618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Herrell R, Goldberg J, True WR, Ramakrishnan V, Lyons M, Eisen S, Tsuang MT: Sexual orientation and suicidality: a co-twin control study in adult men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:867-874Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL: Marriage protection and marriage selection—prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Soc Sci Med 1996; 43:113-123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Hawton K: Sex and suicide: gender differences in suicidal behaviour. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:484-485Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Thorslund J: Ungdomsselvmord og moderniseringsproblemer blandt Inuit i Grønland [Youth Suicide and Modernization in Greenland]. Holte, Denmark, Forlaget SOCPOL, 1992Google Scholar

35. Shiang J: Does culture make a difference? racial/ethnic patterns of completed suicide in San Francisco, CA 1987-1996 and clinical applications. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1998; 28:338-354Medline, Google Scholar

36. Murphy GE, Wetzel RD: Family history of suicidal behavior among suicide attempters. J Nerv Ment Dis 1982; 170:86-90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D: Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1155-1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB: Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case-control study based on longitudinal registers. Lancet 2002; 360:1126-1130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Cleiren M, Diekstra RF, Kerkhof AJ, van der Wal J: Mode of death and kinship in bereavement: focusing on “who” rather than “how.” Crisis 1994; 15:22-36Medline, Google Scholar

40. Appleby L: Prevention of suicide in psychiatric patients, in The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Edited by Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2000, pp 617-630Google Scholar