Agitated Depression in Bipolar I Disorder: Prevalence, Phenomenology, and Outcome

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study aimed to explore how prevalent agitated depression is in bipolar I disorder, whether it represents a mixed state, and whether it differs from nonagitated depression with respect to course and outcome. METHOD: From 313 bipolar I patients with an index episode of major depression, the authors selected those fulfilling Research Diagnostic Criteria for agitated depression. These 61 patients were compared to 61 randomly recruited bipolar I patients with an index episode of nonagitated depression and 61 randomly recruited bipolar I patients with an index episode of mania regarding demographic, historical, and clinical features. The two depressive groups were also compared regarding time to recovery from the index episode, treatment received for that episode, percentage of time spent in an affective episode during a prospective observation period, and 5-year outcome. RESULTS: Patients with agitated depression were consistently not elated or grandiose, but one-fourth had the cluster of symptoms with racing thoughts, pressured speech, and increased motor activity, and one-fourth had the paranoia-aggression-irritability cluster. Compared to patients with nonagitated depression, they had a longer time to 50% probability of recovery from the index episode, were more likely to receive standard antipsychotic drugs during that episode, and spent more time in an affective episode during the observation period. CONCLUSIONS: The occurrence of agitated depression in bipolar I disorder is not rare and has significant prognostic and therapeutic implications. Whether the co-occurrence of a major depressive syndrome with one or two of these symptomatic clusters makes up a “mixed state” remains unclear.

The depressive phase of bipolar disorder has been often described as marked by psychomotor retardation. Goodwin and Jamison (1), in reviewing the literature on the phenomenology of bipolar disorder, stated that “activity and behavior are almost always slowed in bipolar depression.” Beigel and Murphy (2) reported that “the unipolar patient, when he is depressed, is significantly more active, verbal, and openly hostile than the bipolar patient, who is more likely to be physically retarded.” Himmelhoch et al. (3) described “agitated psychotic depression associated with severe hypomanic episodes” as a “rare syndrome,” which occurred in only 12 out of 550 subjects with manic-depression illness who were treated during 7 years. However, Mitchell et al. (4) noticed that, when the comparison was limited to patients with endogenous depression, there was a tendency for bipolar depressed patients to be rated as more agitated than unipolar ones; Spitzer et al. (5) found that agitated depression, defined according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (6), occurred in 29% of bipolar I patients versus 24% of those with recurrent major depression, and Koukopoulos et al. (7) reported that 27% of depressed bipolar I patients, compared with 25% of patients with nonbipolar depression, suffered from “anxious-excited depression.”

“Excited depression” was classified by Kraepelin (8) as a mixed state, and his pupil, Weygandt (9), was the first to use the term “agitated depression,” referring to a mixed state characterized by a depressed mood, psychomotor agitation, and flight of ideas. These views were widely debated at the beginning of the 20th century, with some authors (10–12) agreeing that agitated depression was a mixed state, and others (13, 14) maintaining that psychomotor agitation was just a manifestation of severe anxiety.

The idea that agitated depression represents a full major depressive syndrome accompanied by subsyndromal mania, just as dysphoric mania can be conceptualized as a full manic syndrome accompanied by subsyndromal depression, has been recently revived by several authors (7, 15–19). Akiskal and Mallya (15) described 25 cases of “resistant” depression characterized by unrelenting dysphoria-irascibility, severe agitation, refractory anxiety, unendurable sexual excitement, intractable insomnia, suicidal obsessions and impulses, and “hystrionic” demeanor but genuine expressions of intense suffering and concluded that this cluster was “compatible with a mixed state.” Koukopoulos et al. (7) reported on 46 cases of anxious-excited depression, consisting of depressed mood, inner tension, restlessness, racing thoughts, despair, emotional lability, irritability, suicidal ideas and impulses, initial or middle insomnia, and occasional aggressiveness and sexual excitement. They described the “inner agitation” of these patients as a “great energy that strikes and possesses their minds and sometimes their bodies too,” a force that “is so violent that it cannot be anything but manic in nature” (16). They proposed a set of diagnostic criteria for “mixed depression,” requiring the occurrence of a major depressive episode and at least two of the following symptoms: motor agitation, psychic agitation or intense inner tension, and racing or crowded thoughts (16). Perugi et al. (17, 18) reported on two samples of patients with a “depressive mixed state” consisting of agitation, psychotic depression with irritable mood, pressured speech, and/or flight of ideas. An elated, expansive, or irritable mood was present in 76% of the first patient group and 65.6% of the second; inflated self-esteem or grandiosity in 16% and 15.6%, respectively; a decreased need for sleep in 4% and 6.2%; and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with potential painful consequences in 12% and 9.4%, respectively. However, Swann et al. (20) found that, in a sample of patients with agitated depression defined according to the RDC, scores for mania were minimal, resembling scores for depression in subjects with nonmixed mania. Furthermore, Schatzberg and DeBattista (21) listed several differential criteria between agitated depression and a mixed episode, including the lack, in the former condition, of grandiosity, a stated decreased need for sleep, external distractibility (in agitated depression, distractibility is internally driven), an increase in goal-directed activities (in agitated depression, the agitation is purposeless), and an increased interest in pleasurable activities.

Thus, the prevalence and the nature of agitated depression in bipolar disorder represent a matter of controversy. The importance of this issue is not only theoretical. Agitated depression is consistently regarded as a condition that is difficult to treat and, contrary to retarded depression, is often not responsive to and can even be exacerbated by antidepressants (3, 7, 15–18, 21). Moreover, patients with major depression in whom there is “a mental alertness, associated with tense, apprehensive, and restless behavior” have been described as “the most dangerous type of patients with mental disease, so far as suicide is concerned” (22). If the occurrence of agitated depression in bipolar disorder is not rare, specific recommendations must be developed for its management. If it represents a mixed state, treatment options that are preferred in dysphoric mania will have to be considered.

The present study aimed to approach this issue by providing a tentative answer to the following questions:

| 1. | What is the prevalence of agitated depression among bipolar I patients seen at a center specialized in the management of affective disorders? | ||||

| 2. | Are patients with agitated bipolar depression different from those with nonagitated bipolar depression with respect to any demographic or historical feature? | ||||

| 3. | Is the clinical picture of agitated bipolar depression different from that of nonagitated bipolar depression with respect to any feature, besides those included in the definition of the former condition, and in particular, are manic features significantly more frequent in agitated than in nonagitated depression? | ||||

| 4. | What are the similarities and the differences between the clinical picture of agitated bipolar depression and that of mania? | ||||

| 5. | Is agitated bipolar depression treated differently from nonagitated bipolar depression in clinical practice? | ||||

| 6. | Are the course and the outcome of agitated bipolar depression significantly different from those of nonagitated bipolar depression? | ||||

| 7. | Is the pattern of agitated depression consistent over consecutive depressive episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder? | ||||

Method

Subjects and Procedures

The study was carried out at the Centre for Affective Disorders of the First Psychiatric Department of Naples University between January 1, 1978, and December 31, 1996, after approval of the protocol by the university’s review board. We selected those who met the RDC for agitated depression from among all consecutive new inpatients and outpatients who had an index episode fulfilling RDC for major depression, who gave written informed consent to participate in the study, who could be interviewed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (23), and who received a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder according to the RDC. For each enrolled patient with agitated bipolar depression, we randomly recruited from the same center, during the same year, one patient with an index episode of nonagitated major depression and a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and one bipolar I patient with an index episode of mania (according to RDC, as ascertained by the SADS). The SADS was administered by trained psychiatrists whose interrater reliability had been formally tested and found to be satisfactory (see reference 24).

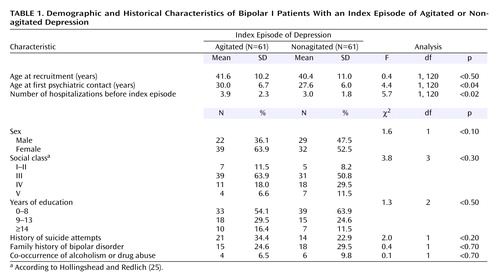

At the time of recruitment, the following demographic and historical variables were recorded for each patient: sex, age, social class (according to Hollingshead and Redlich [25]), years of education, age at first psychiatric contact, number of previous hospitalizations in a psychiatric ward, history of suicide attempts, history of bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives (as assessed by the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria [26]), and co-occurrence of alcoholism or drug abuse (according to the RDC). The symptomatological features of the index episode at its peak were assessed in each patient by the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (27), which was administered by trained psychiatrists whose interrater reliability had been formally tested and found to be satisfactory (see reference 24). The psychiatrists were not aware of the group to which each patient belonged.

Starting from the time of recruitment, each patient with an index episode of agitated or nonagitated depression was examined every second month, by use of the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale and the version of the SADS for measuring change (SADS-C). Treatment was not under the control of the researchers but was carefully recorded at each visit. New affective episodes were recorded and classified according to the RDC. Five years after recruitment, all patients, whether or not they were still attending the center, were contacted for a brief interview, during which the Strauss-Carpenter Outcome Scale (28) was administered by a trained psychiatrist (see reference 29) who was not aware of the group to which each patient belonged.

Data Analysis

Patients with agitated versus nonagitated depression were compared with respect to demographic and historical variables using analysis of variance or the chi-square test with Yates’s correction, as appropriate. The chi-square test with Yates’s correction was used to compare patients with agitated depression, nonagitated depression, and mania with respect to the RDC/SADS profile (percentage of manic and depressive items rated as positive). Analysis of variance was adopted to compare the three patient groups with respect to mean scores on individual Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale items.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the probability of recovery from the index episode in patients with agitated versus nonagitated depression. Differences between them were explored with the log-rank test. Recovery was defined as a period of at least 8 consecutive weeks in which the mood disturbance required by the RDC criterion A for mania, hypomania, or major depression was not present.

Analysis of variance was used to compare the percentage of time spent in an affective episode during the observation period (whatever its duration) by patients with an index episode of agitated versus nonagitated depression. Analysis of variance was also used to compare these two patient groups with respect to the mean global score on the Strauss-Carpenter Outcome Scale at the 5-year follow-up interview. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was used to explore the consistency between the index episode and each of the depressive episodes recorded during the observation period with respect to the RDC subtype of depression (agitated versus nonagitated).

Results

Of the 313 consecutive new patients with an index episode of major depression and a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder seen during the study period, 61 (19.5%) met the RDC for agitated depression. They were 22 men and 39 women, with a mean age at the time of recruitment of 41.6 years (SD=10.2, range=23–64). The two comparison groups consisted of 61 patients with an index episode of nonagitated depression and a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (29 men and 32 women; mean age 40.4 years, SD=11.0, range=23–65) and 61 bipolar I patients with an index episode of mania (30 men and 31 women; mean age 39.4 years, SD=10.9, range=21–59). Patients with agitated depression, compared to those with nonagitated depression, were significantly older at the time of first psychiatric contact and had a significantly higher number of hospitalizations in a psychiatric ward before the index episode (Table 1).

The RDC/SADS profile of the patients with agitated depression differed from that of patients with nonagitated depression in several respects. Besides being significantly more likely to present physical restlessness/psychomotor agitation and increased talkativeness (as expected on the basis of the RDC definition of agitated depression), the former patients also displayed irritability, flight of ideas or racing thoughts, distractibility, and sexual hyperactivity with a significantly higher frequency and were significantly less likely to show psychomotor retardation, loss of energy or fatigability, and loss of interest in usual activities. Delusional guilt occurred in 15 patients with agitated depression (24.6%) and in four with nonagitated depression (6.6%) (χ2=6.2, df=1, p<0.01). Mood-incongruent delusions and hallucinations were absent in the patient groups recruited for this study because they are incompatible with a diagnosis of major depression or mania according to RDC (contrary to DSM-IV). No patient with agitated depression had an elated mood or inflated self-esteem, only one reported a decreased need for sleep or an excessive involvement in activities with potentially painful consequences, and only two were more active than usual socially or at work (Table 2).

Compared to those with mania, patients with agitated depression were significantly more likely to present each of the symptoms and signs included in the RDC definition of major depression, except for poor or increased appetite, sleeping too much, and psychomotor retardation, whereas they were significantly less likely to present each of the symptoms and signs included in the RDC definition of mania, except for irritable mood and physical restlessness (Table 2). Seven patients with agitated depression also fulfilled the RDC for mania, while eight manic patients also met the RDC for probable major depression and three met the RDC for definite major depression (the RDC do not have a distinct category for mixed states, contrary to DSM-IV). On the other hand, 24 patients with agitated depression (39.3%) did not show any of the symptoms and signs included in the RDC definition of mania except for physical restlessness (required by definition).

On the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale, the patients with agitated depression had significantly higher mean scores than those with nonagitated depression on the items regarding hostility, pressure of speech, flight of ideas, agitation, inner tension, suicidal thoughts, labile emotional responses, and ideas of persecution (this last item, in the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale, includes also undue suspiciousness and exaggerated self-consciousness). Compared to patients with mania, those with agitated depression had significantly higher mean scores on the items regarding depressed mood, inner tension, pessimistic thoughts, and suicidal thoughts, and significantly lower mean scores on the items regarding elation, pressure of speech, flight of ideas, ideas of grandeur, reduced sleep, increased sexual interest, increased energy, and disinhibition (Table 3). Of note, all patients with agitated depression scored 0 on the items for elation, ideas of grandeur, and increased energy, and all but three scored 0 on the item “disinhibition.”

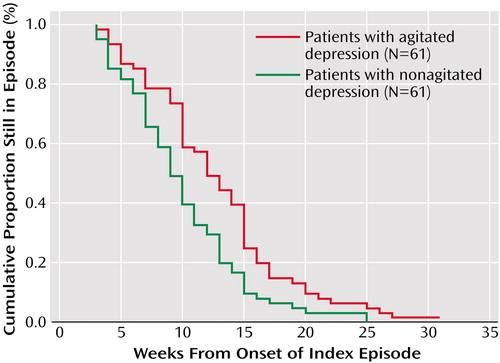

The time to 50% probability of recovery from the index episode was significantly longer in the patients with agitated versus nonagitated depression: 12 weeks (95% CI=10.1–13.9) versus 9 weeks (95% CI=7.7–10.3); log-rank=8.6, df=1, p<0.003 (Figure 1). A total of 52 patients with agitated depression (85.2%) and 57 patients with nonagitated depression (93.4%) received antidepressants during the index episode (χ2=1.4, df=1, p<0.20). In 12 patients with agitated depression (23.1%), one or more antidepressants were discontinued because of worsening of symptoms; this occurred in five patients with nonagitated depression (8.7%) (χ2=3.2, df=1, p<0.07). Twenty-two patients with agitated depression (36.1%) versus eight of those with nonagitated depression (13.1%) received standard antipsychotic drugs during the index episode (χ2=7.5, df=1, p<0.006). Nine patients with agitated depression (14.6%) versus four with nonagitated depression (6.6%) switched from depression to mania during the index episode (χ2=1.4, df=1, p<0.20).

All patients with agitated and nonagitated depression were evaluated every second month for at least 3 years, and 83.6% of the former and 85.2% of the latter for the entire period of 5 years. Patients with an index episode of agitated depression were experiencing an affective episode during the observation period for a significantly higher percentage of time (mean=24.3%, SD=11.6%) than those with an index episode of nonagitated depression (mean=18.5%, SD=10.8%) (F=8.1, df=1, 120, p<0.005). Of the 35 patients with an index episode of agitated depression who had at least one further depressive episode during the observation period, 23 (65.7%) had only depressive episodes fulfilling the RDC for the agitated subtype. Of the 32 patients with an index episode of nonagitated depression who had at least one further depressive episode, 28 (87.5%) had only episodes not fulfilling the RDC for agitated depression. Cohen’s kappa coefficient measuring the consistency of the diagnosis of agitated depression during the observation period ranged from 0.58 to 0.68.

The 5-year follow-up interview was possible in 53 patients with agitated depression (86.9%) and in 55 of those with nonagitated depression (90.2%). Among both patient groups, patients who were lost to follow-up did not differ significantly from the others with respect to baseline clinical features. The mean global score on the Strauss-Carpenter Outcome Scale was not significantly different in patients with an index episode of agitated depression (mean=10.7, SD=2.1) compared to those with nonagitated depression (mean=11.0, SD=2.1) (F=0.4, df=1, 106, p<0.50).

Discussion

This study, the largest carried out as yet on agitated depression in bipolar I disorder, confirms that this condition is not at all rare, although the observed prevalence (19.5%) was somewhat lower than that reported by Spitzer et al. (5) and Koukopoulos et al. (7) (29% and 27%, respectively). Patients with agitated bipolar I depression, compared to those with nonagitated depression, tend to have the first psychiatric contact at a later age and to be hospitalized more frequently in a psychiatric ward.

Is agitated bipolar I major depression, as defined by the RDC, a mixed state? Most probably, not in all cases, since more than one-third of our agitated depressive patients did not present any of the symptoms and signs included in the RDC definition of mania, except for physical restlessness (required by definition). However, 14 of our patients with agitated depression (23.0%) presented three of the four symptoms and signs included by Cassidy et al. (30) in factor 2 for mania (racing thoughts, pressured speech, and increased motor activity; the fourth sign, increased contact, is not considered either in the RDC or in the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale). Fourteen of our patients (23.0%) had all the symptoms and signs included by the same authors in factor 5 for mania (paranoia, aggression, and irritability; the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale item “hostility” corresponds to “aggression,” as defined by Cassidy et al. [31]). Eight of our patients (13.1%) showed both three symptoms and signs of factor 2 and all the symptoms and signs of factor 5. It is important to emphasize that the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale item “agitation,” more explicitly than the item “increased motor activity” of Cassidy et al., refers to purposeless physical restlessness as opposed to an increase in goal-directed activities.

In our group, the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale “agitation” or RDC “physical restlessness” was present in 100% of the patients with agitated depression and 96.7% of those with mania, whereas the RDC subitem “more active than usual socially or at work” was rated as positive in 90.2% of the patients with mania but only in 3.3% of the patients with agitated depression. This is a major difference and corresponds to one of the differential criteria between agitated depression and a mixed bipolar episode proposed by Schatzberg and DeBattista (21). However, one other differential criterion suggested by these authors was not validated by our data: Schatzberg and DeBattista maintained that distractibility in agitated depression is “internally driven” rather than “external,” whereas one-third of our patients with agitated depression presented distractibility as defined by the RDC (i.e., “attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli”).

Also noteworthy is that 16.4% of our patients with agitated depression showed sexual hyperactivity, a symptom which is certainly not typical of major depression but was mentioned by Akiskal and Mallya (15), Koukopoulos et al. (7, 16), and Perugi et al. (17, 18) in their descriptions of agitated depression as a mixed state. On the other hand, inflated self-esteem (present in 16% and 15.6%, respectively, of the patients with mixed depression described by Perugi et al. [17, 18]) was totally absent in our group, and excessive involvement in activities with potentially painful consequences was present in only one of our patients (1.6%), compared with the 12% and 9.4% reported by Perugi et al. (17, 18) in their two samples. Thus, in summary, our patients with agitated bipolar I depression were consistently not elated or grandiose, but one-fourth of them had the racing thoughts-pressured speech-increased motor activity cluster and one-fourth had the paranoia-aggression-irritability cluster. What is the specificity of these clusters for mania? Does the co-occurrence of one or both of these clusters with a major depressive syndrome make up a “mixed state”? Relevant to this issue is the observation that, out of the eight patients with a diagnosis of mania recruited in our study who also fulfilled the RDC for probable major depression (i.e., patients who would receive today a diagnosis of depressive or dysphoric mania), only two were either elated or grandiose, while five presented the racing thoughts-pressured speech-increased motor activity cluster, and five presented the paranoia-aggression-irritability cluster. Apparently, agitated depression and dysphoric mania are partially overlapping conditions.

Our findings confirm that the RDC diagnosis of agitated bipolar I depression has significant prognostic and therapeutic implications (although, of course, extrapolations from group data to individual cases should always be made cautiously). Our patients with that diagnosis, compared to those with nonagitated depression, had a significantly longer time to recovery from the index episode, were more likely to receive standard antipsychotic drugs during the index episode, and spent a significantly higher proportion of time in an affective episode during the observation period. Treatment guidelines and algorithms for bipolar disorder have almost completely ignored this reality up until now. On the basis of our data, should mood stabilizers that are currently preferred for use in dysphoric mania, in particular valproate, also be considered for use in agitated bipolar depression? What is the comparative efficacy of lamotrigine, currently regarded as the most effective mood stabilizer in the depressive phase of bipolar disorder, in agitated versus nonagitated bipolar depression? These are questions open to research.

|

|

|

Received Jan. 7, 2003; revision received May 13, 2003; accepted May 15, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Naples, Naples, Italy. Address reprint requests to Dr. Maj, Clinica Psichiatrica, Primo Policlinico Universitario, Largo Madonna delle Grazie, I-80138 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Cumulative Probability of Remaining in the Index Episode for Bipolar I Patients With Agitated (N=61) Versus Nonagitated (N=61) Depressiona

aThe time to 50% probability of recovery from the index episode was 12 weeks (95% CI=10.1–13.9) in patients with agitated depression and 9 weeks (95% CI=7.7–10.3) in those with nonagitated depression (log rank=8.6, df=1, p<0.003).

1. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-depressive illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

2. Beigel A, Murphy DL: Unipolar and bipolar affective illness: differences in clinical characteristics accompanying depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1971; 24:215–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Himmelhoch JM, Coble P, Kupfer DJ, Ingenito J: Agitated psychotic depression associated with severe hypomanic episodes: a rare syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:765–771Link, Google Scholar

4. Mitchell P, Parker G, Jamieson K, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, Brodaty H, Boyce P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roy K: Are there any differences between bipolar and unipolar melancholia? J Affect Disord 1992; 25:97–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 2nd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1975Google Scholar

7. Koukopoulos A, Pani L, Serra G, Minnai G, Reginaldi D: La dépression anxieuse-excitée: un syndrome affectif mixte. Encephale 1995; 21(special number 6):33–36Google Scholar

8. Kraepelin E: Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch für Studirende und Aerzte, 8th ed. Leipzig, Germany, Barth, 1909Google Scholar

9. Weygandt W: Ueber die Mischzustaende des manisch-depressiven Irreseins. Munich, Lehmann, 1899Google Scholar

10. Dreyfus GL: Die Melancholie, ein Zustandsbild des manisch-depressiven Irreseins. Jena, Germany, Fischer, 1907Google Scholar

11. Specht G: Ueber die Strukture und klinische Stellung der Melancholia agitata. Zentralbl Nervenheilkr Psychiatrie 1908; 39:449–469Google Scholar

12. Thalbitzer S: Die manisch-depressive Psychose: das Stimmungs-irresein. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1908; 43:1071–1127Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Westphal A, Koelpin O: Bemerkungen zu dem Aufstaze von Prof Dr G Specht: Ueber den Angstaffect im manisch-depressiven Irresein. Zentralbl Nervenheilkr Psychiatrie 1907; 18:729–731Google Scholar

14. Stransky E: Das manisch-depressive Irresein. Leipzig, Germany, Deuticke, 1911Google Scholar

15. Akiskal HS, Mallya G: Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:68–73Medline, Google Scholar

16. Koukopoulos A, Koukopoulos A: Agitated depression as a mixed state and the problem of melancholia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22:547–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Micheli C, Musetti L, Paiano A, Quilici C, Rossi L, Cassano GB: Clinical subtypes of bipolar mixed states: validating a broader European definition in 143 cases. J Affect Disord 1997; 43:169–180Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Micheli C, Socci C, Madaro D: Clinical characterization of depressive mixed state in bipolar-I patients: a report from the Pisa-San Diego collaborative study. J Affect Disord 2001; 67:105–114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McElroy SL, Freeman MP, Akiskal HS: The mixed bipolar disorders, in Bipolar Disorders:100 Years After Manic-Depressive Insanity. Edited by Marneros A, Angst J. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer, 2000, pp 63–87Google Scholar

20. Swann AC, Secunda SK, Katz MM, Croughan J, Bowden CL, Koslow SH, Berman N, Stokes PE: Specificity of mixed affective states: clinical comparison of dysphoric mania and agitated depression. J Affect Disord 1993; 28:81–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Schatzberg AF, DeBattista C: Phenomenology and treatment of agitation. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 15):17–20Google Scholar

22. Jameison GR: Suicide and mental disease: a clinical analysis of one hundred cases. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1936; 36:1–12Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Maj M, Veltro F, Pirozzi R, Lobrace S, Magliano L: Pattern of recurrence of illness after recovery from an episode of major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:795–800Link, Google Scholar

25. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1958Google Scholar

26. Endicott J, Andreasen NC, Spitzer RL: Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1975Google Scholar

27. Åsberg M, Montgomery SA, Perris C, Schalling D, Sedvall G: A comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1978; 271:5–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 27:739–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Bartoli L: Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:30–35Link, Google Scholar

30. Cassidy F, Forest K, Murry E, Carroll BJ: A factor analysis of the signs and symptoms of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:27–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Cassidy F, Murry E, Forest K, Carroll BJ: Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:187–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar