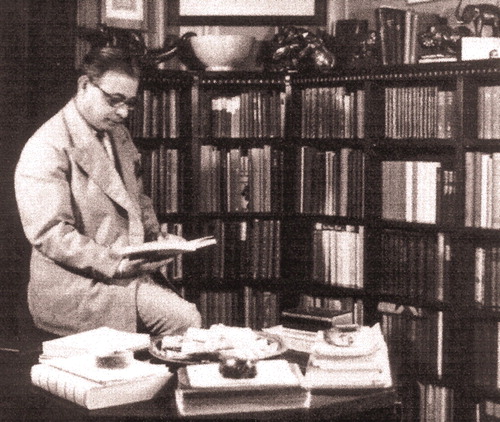

Otto Rank, 1884–1939

Viennese-American psychologist Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud’s protégé, colleague, and prescient critic, had considerable influence on American psychiatry (1–4). Secretary of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society from 1906, at age 22, and Freud’s closest associate for the next 18 years, Rank was a prolific and influential psychoanalytic author in the formative years of the movement. His scope included art, music, literature, anthropology, history, science, and philosophy.

A polymath from a humble background, Rank finished trade school as a locksmith while reading voraciously. Through Alfred Adler, his family doctor, he met Freud, who employed him and sent him to the University of Vienna, where he got his Ph.D. in 1912. (Freud discouraged going to medical school.) By then Rank had published books on art, mythology, incest, and the Lohengrin saga. After World War I he directed training at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute and worked with a number of Americans there. Rank visited the United States in 1924, addressing the American Psychoanalytic Association, which made him an honorary member. But his work with Sandor Ferenczi on a more active psychotherapeutic technique and his controversial book The Trauma of Birth (1924) brought criticism from conservative Freudians. Rank developed a more egalitarian psychotherapy focused on the here-and-now, real relationships, conscious mind, and will, rather than past history, transference, unconscious process, and wish. His ideas on the mother-child relationship and interpersonal psychotherapy are mainstream now, but in 1926 they caused the final break with Freud.

Rank then set up practice in Paris, visiting New York regularly and finally moving there in 1935. Ousted by the psychoanalytic establishment, Rank lectured widely, taught, and practiced psychotherapy in New York. (His first wife, Beata, a lay analyst specializing in children, became a training analyst in Boston, where she died in 1967.) Among his patients and/or seminar students were psychiatrists Marion Kenworthy, Frankwood Williams, Martin Peck, and George Wilbur. Rank’s post-Freudian writings include Psychology and the Soul (1930),Art and Artist (1932),Modern Education (1932),Will Therapy (1936), and Truth and Reality (1936). In October 1939, divorced and remarried, planning to become a citizen and move to California, Rank died of a reaction to sulfonamide at age 55, a month after Freud.

Otto Rank loved his new country, and Mark Twain had become his favorite author, from whom he adopted the nickname “Huck.” Out of favor while analysis was dominant in American psychiatry, Rank came to the attention of a wider public in the writings of Ernest Becker (The Denial of Death [1973]) and Anais Nin. His influence on social work came through the Pennsylvania School, and on psychology through such writers as Paul Goodman, Rollo May, and Esther Menaker. Psychiatrists who acknowledge Rank’s importance in their writings include Franz Alexander, Frederick Allen, Clara Thompson, Judd Marmor, Robert Jay Lifton, Carl Whitaker, and Irvin Yalom.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Lieberman, 3900 Northampton St., N.W., Washington, DC 20015-2951; [email protected] (e-mail).

Otto Rank

1. Rank O: A Psychology of Difference: The American Lectures. Edited by Kramer R. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1996Google Scholar

2. Lieberman EJ: Acts of Will: The Life and Work of Otto Rank. New York, Free Press, 1985; reprint, with a new preface, Amherst, Mass, University of Massachusetts Press, 1993Google Scholar

3. Otto Rank, in American National Biography, vol 18. Edited by Garraty JA, Carnes MC. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999, p 141Google Scholar

4. Lieberman EJ: Otto Rank, psychologist and philosopher ( http://www.ottorank.com )Google Scholar