Impact of Outpatient Commitment on Victimization of People With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to evaluate the effectiveness of outpatient commitment in reducing victimization among people with severe mental illness. METHOD: One hundred eighty-four involuntarily hospitalized patients were randomly assigned to be released (N=99) or to continue under outpatient commitment (N=85) after hospital discharge. An additional group of patients with a recent history of serious violent behavior (N=39) was nonrandomly assigned to at least a brief period of outpatient commitment following hospital disharge. All three groups were followed for 1 year, and case management services plus additional outpatient treatment were provided to all subjects. Outcome data were based on interviews with the patients and informants as well as service records. RESULTS: Subjects who were ordered to outpatient commitment were less likely to be criminally victimized than those who were released without outpatient commitment. Multivariate analysis indicated that each additional day of outpatient commitment reduced the risk of criminal victimization and that outpatient commitment had its effect through improved medication adherence, reduced substance use or abuse, and fewer violent incidents. CONCLUSIONS: Protection from criminal victimization appears to be a positive, unintended consequence of outpatient commitment.

Outpatient commitment is designed to be a less restrictive alternative to involuntary hospitalization for people with mental illness who are at risk of becoming dangerous to themselves or others (1, 2). Many view it as particularly useful for people with severe mental illness who are unable or unwilling to comply with treatment, frequently relapse, become dangerous, and require hospitalization (3–5). In outpatient commitment, patients are ordered by law to the care of a treatment provider, almost always a community mental health center, to receive treatment, services, and supervision deemed necessary to maintain them and to control the symptoms thought to produce their dangerous behavior (2, 6).

From its origin, a purpose of outpatient commitment was to prevent violence directed against themselves or others by people with severe mental illness (2, 4–8). In the late 1990s, advocates for outpatient commitment legislation emphasized rare acts of random violence by people with untreated psychoses to gain support in different states (9). Few considered the potential role of outpatient commitment in preventing harm to people with severe mental illness from others who might attack or victimize them, although there are high rates of victimization among people with severe mental illness (10–12). In this article we examine the impact that outpatient commitment had on reducing victimization of people with severe mental illness.

Research has been accumulating on the high rate of victimization among clinical populations (10–13). One study found that more than three-fifths of newly hospitalized psychiatric patients reported being physically victimized by their partners and that just under half reported being physically victimized by other family members (13). Victimization of people with severe mental illness occurs outside the home as well. On the streets the severely mentally ill are especially vulnerable not only because of impaired judgment and visible symptoms of disorder but also because frequent co-occurring substance abuse and/or poverty place them in areas with high crime rates. A previous report based on the same data used in the current study found that people with severe mental illness in both rural and urban localities were 2.5 times more likely than the general population to be victims of violent crime (11). Homelessness increases the risk of victimization.

Outpatient commitment may reduce victimization indirectly by increasing patients’ long-term participation in community treatment and services, which will, in turn, improve their mental health and social functioning and eventually lower their risk of exposure to crime and violence. Specifically, outpatient commitment might reduce victimization by helping an individual obtain more stable housing. A regular residence in which to sleep, eat, and spend time would reduce homelessness and the attendant high rate of physical and sexual assault. Additionally, provision of other services such as psychosocial therapy and rehabilitation could reduce exposure to victimization. Assistance with obtaining income support and help with money management could reduce the need for theft and other illegal behaviors that tend to place people in the company of dangerous individuals who victimize them.

Medication adherence can be expected to reduce symptoms of severe mental illness and thus reduce victimization. Psychotic symptoms and bizarre behavior can lead to tense and conflictual situations (14), which, in turn, may result in a patient’s victimization—either because others become violent toward the patient or because the patient lashes out physically and others react with stronger violence. By facilitating adherence and ensuring more consistent follow-up, outpatient commitment may lead to reduced symptoms, better functioning in social relationships, and improved judgment (15). In turn, these changes should lessen a person’s vulnerability to abuse by others and lower the probability of becoming involved in dangerous situations where victimization is more likely.

Finally, to the extent that medication and psychosocial treatment reduce alcohol and drug abuse, they should indirectly reduce victimization by improving perception, judgment, and self-control; diminishing hostility and subsequent provocative behavior; preventing exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms; and eliminating the need to seek addictive substances and the means to procure them in perilous places and situations (14–16).

Through these multiple influences, outpatient commitment should reduce victimization among people with severe mental illness. In this article we focus on reduction of criminal victimization, using 12 months of follow-up data from a study of outpatient commitment for people with severe mental illness. We tested the effect of outpatient commitment on victimization in two sets of multivariate models. The first set has controls for baseline characteristics that are hypothesized to be associated with victimization (10, 11, 16). The second set has tests for the mechanisms (mediating variables) through which we expect outpatient commitment to affect criminal victimization: medication compliance, substance abuse, and dangerous situations.

North Carolina, the study site, permits commitment to psychiatric inpatient facilities on the basis of mental illness and danger to self or others and encourages outpatient commitment as a less restrictive alternative for people meeting these criteria. North Carolina also permits outpatient commitment for people who are mentally ill but not currently dangerous if they have 1) the capacity to survive safely in the community with available supports, 2) a history of need for treatment to prevent deterioration that would predictably result in dangerousness, and 3) a mental status that limits or negates their ability to make an informed decision to seek or comply voluntarily with recommended treatment. A district court judge in a civil commitment hearing can order mandatory outpatient commitment for a period not to exceed 90 days. Outpatient commitment can be renewed for successive periods of 180 days if a judge in a new hearing finds the criteria are still met. The order designates a treatment facility but no treatment plan, leaving determination of type, amount, and frequency of medication and services to clinical decisions. If a patient fails to adhere to the recommended treatment, the clinician may request that a law officer escort the patient to the community provider for examination and hopeful persuasion to accept treatment. Medication may not be forced, however, and involuntary hospitalization can occur only with a new commitment procedure.

Method

This analysis used longitudinal data on 223 subjects enrolled in the Duke Mental Health Study, to our knowledge the first randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of outpatient commitment (8). Subjects were involuntarily admitted patients with severe mental illness who were recruited from a state mental hospital and three general hospitals serving the catchment areas of participating mental health centers. Since involuntary admission accounts for about 90% of the admissions to state mental hospitals in North Carolina, patients admitted under this status are representative of the patient population with severe and persistent mental disorders, particularly the subgroup of repeatedly admitted patients in the public mental health system.

To be eligible, subjects had to be 18 years of age or older; be residents of participating counties; have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective or other psychotic disorder, or major affective disorder with a duration of at least 1 year; have significant functional impairment; have received intensive treatment within the past 2 years. Due to safety and liability concerns, subjects with a recent history of assaultiveness (causing injury to someone or using a weapon to harm or threaten someone) could not be randomly assigned to release from outpatient commitment but are included in the study as a nonrandomly assigned comparison group.

Between November 1992 and March 1996, we identified eligible patients from daily hospital admission records and discussion with treatment teams. While subjects were awaiting court-ordered outpatient commitment, we offered them improved access to services by means of case management, monetary remuneration for each follow-up interview, and possible random assignment to release from their outpatient commitment orders. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects. Of 374 identified eligible patients, only 43 (11.5%) refused to participate.

We randomly assigned subjects either to continue under their outpatient commitment orders or to be released from outpatient commitment. All subjects were discharged to participating mental health centers in nine contiguous urban and rural counties, where they received case management plus additional services according to locally developed treatment plans.

Although outpatient commitment is designed to protect society and to serve patient welfare, available studies were unclear as to whether outpatient commitment or accompanying services accomplished these goals (17). Because of the substantial evidence available before we began our study that services made a difference in patients’ well-being and the argument that it was services and not the law’s coercion that made the difference in previous outpatient commitment studies, we randomly assigned subjects to outpatient commitment while giving all subjects improved access to services through case management, a service not generally available in the area. Intensity of treatment varied, but uniformity existed in the treatment adherence protocol by which clinicians promptly rescheduled missed appointments. For an outpatient commitment subject at the threshold of three consecutive missed appointments, mental health centers obtained a pick-up order from the court clerk for the sheriff to bring the subject immediately for evaluation and hopeful persuasion to accept treatment. Comparison subjects at the threshold of three consecutive missed appointments received prompt unscheduled home visits and counseling about the consequences of treatment nonadherence. Alternatively, mental health centers could seek a court hearing to determine eligibility for inpatient commitment for subjects in either group. The study protocol permitted earlier intervention before three missed appointments if clinically indicated. Mental health center compliance with the treatment adherence protocol was excellent.

Initial outpatient commitment orders could vary by up to 90 days. Before initial orders lapsed, we notified clinicians of the need to reevaluate outpatient commitment legal criteria and seek recommitment if appropriate. These determinations created variability in the total length of outpatient commitment orders. If a subject were rehospitalized, the hospital could reinitiate outpatient commitment procedures. Subjects in the comparison group were “immunized” from outpatient commitment for the year (the same logic was used in immunizing comparison subjects from outpatient commitment during the year of follow-up as was used in removing them from outpatient commitment at the beginning of the study). Comparison subjects who were inadvertently given outpatient commitment were released from the order. Involuntary or voluntary hospital admissions occurred in both groups as clinically indicated.

An exception to the randomization procedure was necessary for 67 subjects with a history of serious assault involving weapon use or physical injury to another person within the preceding year. These subjects underwent an initial period of outpatient commitment—up to 90 days—as ordered by the court, but clinicians and the courts determined renewals. This violent group was included because it represents a key population to which outpatient commitment is targeted. Since they varied in renewal of court orders beyond initial periods and in the number of services received, as did randomly assigned group members, their outcomes could be analyzed by duration of commitment and frequency of services. Our multivariate analysis of the pooled data from all subjects incorporates a statistical control for inclusion of this nonrandomly assigned, seriously violent group.

Data collection procedures have been described elsewhere (2, 5, 8). Briefly, at baseline we conducted structured interviews with each subject and a family member or other informant who knew the respondent well. Follow-up interviews were conducted with the subject, a collateral informant, and the case manager at 4, 8, and 12 months. Hospital records supplemented baseline interviews and, along with mental health center records, provided information on follow-up services and treatment. Diagnoses from hospital discharge summaries showed high levels of agreement with results of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18) conducted on a subgroup of 100 patients.

We interviewed 223 (184 randomly assigned and 39 not randomly assigned) of the original 331 subjects at the 12-month follow-up. Attrition in the outpatient commitment and comparison groups was random: almost all differences in distribution of their baseline characteristics were not significant. Most important, there was no significant difference between groups in baseline victimization. We found two baseline clinical differences between the two groups: those ordered to outpatient commitment had lower levels of insight (19) and were more likely to be noncompliant than the comparison group. These differences tend to operate against our hypothesis that outpatient commitment reduces criminal victimization; thus, any support we found was a conservative estimate.

We measured criminal victimization at baseline and at each of the three follow-up interviews by subject responses to two questions: In the past 4 months, have you been a victim once or more than once of violent crime, such as assault, rape, or mugging? and Have you been a victim of a nonviolent crime, such as burglary, theft of property or money, or being cheated? A positive response at any interview indicating the occurrence of at least one incident of violent or nonviolent criminal victimization during the study year was our dependent variable.

Information on our three mediating variables was derived from interviews with subjects, case managers, and collateral informants. We defined medication noncompliance as never or only sometimes taking prescribed psychotropic medications as prescribed. We defined substance use as drinking alcohol or using illicit drugs once to several times per month or more frequently. We defined substance abuse as the occurrence of any problems with family, friends, job, police, or physical health related to alcohol or drug use, or a diagnosis of psychoactive substance use disorder.

We measured dangerous situations indirectly by violent incidents involving subjects. Respondents were asked whether they had been picked up by police or arrested for physical assault on another person, had been in fights involving physical contact, or had threatened someone with a weapon. Case managers and collateral informants responded to comparable questions about subjects. A composite index indicated whether at least one violent incident was reported by any interviewee during the study year (5). It is unlikely that violent incidents and criminal victimization tap the same encounters among our subjects because most of their violence occurs in homes involving family and friends. Such domestic assaults tend not to be reported as criminal victimization (13). Also, most subject criminal victimization tends to be nonviolent.

Mental health center service records provided information on treatment and services. We summed all encounters for case management, medication, psychotherapy, and other services in an outpatient services utilization index. Four other predictor variables included psychiatric symptoms, functional impairment, insight, and social support. The total score of symptoms and the paranoid symptoms subscale score of the Brief Symptom Inventory (20) provided measures of psychiatric symptoms. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (21) indicated functional status and severity of psychiatric disturbance rated on a continuum of 0 to 100 from most to least impaired. The Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (19) assessed insight defined as the ability of people with severe mental illness to recognize their illness and need for treatment. The Duke Social Support Scale (8) provided a measure of respondents’ subjective perceptions of their value in a social network, whether the network would provide help if needed, and satisfaction with the quantity and quality of received support.

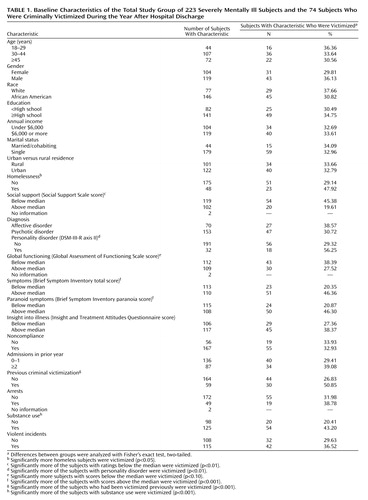

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study group as a whole. These subjects were mainly young adults, slightly more of whom were men (53.4%), about two-thirds African American, of low educational attainment (36.8% did not graduate from high school), and of low annual income (mean=$7,814). Only about one-fifth of the subjects were married or cohabiting, and just over half were living in cities/suburbs; the rest were living in small towns and rural areas. Just over one-fifth were homeless in the 4 months before the index hospitalization. These characteristics closely match the sociodemographic composition of subjects initially screened for the study and of the severely mentally ill population in the state hospital.

Clinically the study group was composed predominantly of people with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other psychosis (68.6%); the rest had a mood disorder. Subjects had moderate functional impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale median score=47) (18, 22), averaged 1.4 psychiatric hospital admissions in the year before the baseline hospitalization, and had high noncompliance rates (74.9%). In the 4 months before hospitalization, 56.1% used alcohol or illicit drugs; of the 128 subjects who used substances, 79—nearly two-thirds—had family, work, or legal problems related to substance abuse. Violent incidents were common (51.6%), and 22.0% had been picked up or arrested by police.

Results

Seventy-four respondents (33.2%) reported being criminally victimized at least once during the follow-up period: 22 (9.9%) suffered violent victimization, and 64 (28.7%) suffered nonviolent victimization (12 were victimized both violently and nonviolently). These figures reflect only a slight increase over the proportion of criminal victimization in the 4 months before baseline (27.2%, 8.2%, and 22.4%, respectively). The rate of nonviolent victimization was slightly higher than the national annual rate of 21.1%, but the violent victimization rate was more than three times as high as the national rate of 3.1% (23).

Table 1 presents the unadjusted baseline predictors of victimization in the follow-up period. Only perceived social support significantly lowered the risk of criminal victimization; homelessness, symptoms, paranoid symptoms (21), previous victimization, substance use, and a personality disorder diagnosis significantly elevated the risk. We also found that subjects who reported being victimized had more outpatient service encounters during the year, on average, than their counterparts who were not victimized (9.1 service events per month compared with 6.0 service events per month) (F=3.87, df=1, 221, p=0.05).

The simple relationship between outpatient commitment and criminal victimization was significant in the hypothesized direction among the randomly assigned subjects. The 85 subjects who were ordered to outpatient commitment were significantly less likely than the 99 comparison subjects to have had any criminal victimization during the follow-up period (N=20 [23.5%] versus N=42 [42.4%]) (χ2=6.5, df=1, p<0.01). Furthermore, risk of victimization decreased with increased duration of outpatient commitment—from 42.4% [N=42] among the subjects in the comparison group (no outpatient commitment) to 26.1% [N=12] among the 46 subjects with less than 6 months of outpatient commitment, to 20.5% [N=8] among the 39 subjects with 6 months or more of outpatient commitment (χ2=7.6, df=2, p<0.05). This same relationship held when the nonrandomly assigned seriously violent group was added.

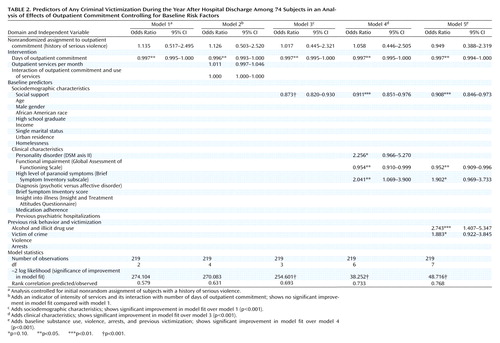

We estimated a series of logistic regression models to test the effect of outpatient commitment on criminal victimization controlling for other predictors of victimization. Complete data were available on all variables for 219 subjects, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Variable reduction, necessitated by the large number of potential predictors, was accomplished through a series of staged analyses. In all stages we controlled for the nonrandomly assigned group with a history of serious violence by first entering a dichotomous variable for membership in this group. Second, in all stages we entered a continuous variable indicating days in outpatient commitment. We selected other variables stepwise at each stage for the subsequent stage if p<0.10.

Table 2 presents the effect of outpatient commitment and baseline predictors on criminal victimization in the 12-month follow-up period. Model 1 shows that increasing the number of days on outpatient commitment significantly reduced the odds of victimization when we controlled for initial nonrandom assignment of subjects with a history of serious violence. Model 2 adds an indicator of intensity of services and its interaction with number of days of outpatient commitment. Neither had a significant effect on criminal victimization. Model 3 adds sociodemographic characteristics and shows that only perceived social support exerted a significant independent effect. Higher levels of perceived social support reduced the odds of victimization. Model 4 introduces clinical characteristics. Personality disorder and a high level of paranoid symptoms each more than doubled the odds, while better functioning (higher Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score) reduced the odds of criminal victimization. Finally, model 5 adds baseline substance use, violence, arrests, and previous victimization. Neither earlier violence nor arrests was significantly associated with criminal victimization, but alcohol and illicit drug use almost tripled the odds and previous criminal victimization almost doubled the odds of criminal victimization during the study year. Personality disorder lost significance and dropped out as a predictor when these two variables were added. This set of models shows that outpatient commitment exerted an independent effect on reduced criminal victimization that was not diminished by patient characteristics; number of days of outpatient commitment maintained statistical significance in the presence of controls for baseline predictors of victimization.

The odds ratio of days of outpatient commitment, 0.997, indicates that the risk of victimization was reduced on average about one-third of 1% (0.003) for each additional day of outpatient commitment. This small change in risk per day adds up to a large change over months; specifically, it adds up to a 10% reduction over 1 month and a larger percentage change over multiple months.

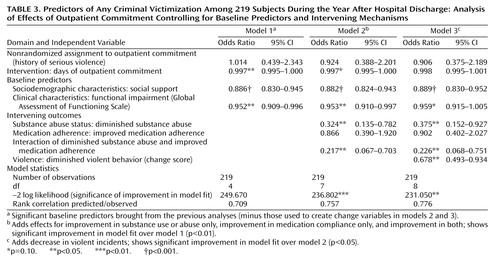

To test our hypothesis that outpatient commitment reduces the risk of criminal victimization by improving treatment adherence, which reduces substance abuse and the likelihood of being in dangerous situations, we examined in a second set of models with medication nonadherence, substance use or abuse, and violent incidents as mediating variables through which outpatient commitment affected victimization (Table 3). As in the previous analyses (Table 2), these models included in each stage the control variable for nonrandom assignment (the seriously violent group) and days of outpatient commitment.

We constructed change score variables for substance use or abuse, medication compliance, and the combination of these two (correlated) variables. Substance use or abuse was coded as a three-level variable (0=no use, 1=use without problems, 2=diagnosis or problems with substance abuse reported from any source) for two time frames: baseline (4 months before hospitalization) and 12-month summary. The difference between values for these two variables constituted the change score on substance use or abuse. Subjects scoring 0 (no change) were recoded so that a higher score was assigned for maintaining a more favorable status (e.g., staying drug-free) than for maintaining a poor status.

Similarly, we constructed a change score for medication adherence, incorporating all sources of information to determine whether the subject had failed to take medications as prescribed or only took them some of the time. On the basis of the distribution of these change scores and to facilitate categorical analysis, we constructed dichotomous variables measuring any improvement versus no improvement in medication adherence and substance abuse. (About one-third of the study group improved on each of these measures.) Finally, we tested the interaction effect of these change variables using logistic regression with dummy coding for three dichotomous effects: improved adherence only, diminished substance abuse only, and the combination of improved adherence and diminished substance abuse (5, 24).

Model 1 presents the significant baseline predictors brought from the previous analyses (minus those used to create change variables in models 2 and 3). Model 2 adds effects for improvement in substance use or abuse only, improvement in medication compliance only, and improvement in both. Model 3 examines all of these plus decrease in violent incidents. Diminished substance use or abuse and diminished substance use or abuse combined with improved medication adherence significantly reduced criminal victimization. Furthermore, when they were added to the equation, the direct effect of outpatient commitment on criminal victimization was reduced to nonsignificance, as expected. A decrease in violent incidents added in model 3 also significantly reduced the odds of criminal victimization. This second set of models shows that outpatient commitment’s direct effect on criminal victimization is rendered nonsignificant in the presence of these mediating factors; thus, they support the hypothesis that outpatient commitment reduces criminal victimization through improving treatment adherence, decreasing substance abuse, and diminishing violent incidents.

Discussion

As have previous reports from the Duke Mental Health Study (5, 8, 24), we found a positive effect of outpatient commitment in the current study. People with severe mental illness who were ordered by the court to mental health treatment in the community were significantly less likely to be criminally victimized than severely mentally ill comparison subjects who were not court-ordered into treatment. Comparison subjects were almost twice as likely to be victimized as were outpatient commitment subjects, despite both groups’ having case management, individualized treatment plans, and home visitation if they missed three treatment appointments. Additionally, duration of outpatient commitment mattered (victimization risk decreased with more days of outpatient commitment), and outpatient commitment affected victimization by inducing behavioral changes in treatment adherence, substance use or abuse, and avoidance of violent incidents.

Service intensity was not a significant factor, but its lack of significance does not mean that the amount of services received is unrelated to victimization. The significant positive bivariate association between services per month and criminal victimization suggests another causal path: subjects who become criminally victimized receive more services.

Although our design is a randomized controlled trial, it deviates from strict randomization in two ways. It included a subgroup of people who had a recent history of serious violent behavior that prevented their being assigned randomly to the comparison group. Had these subjects been excluded, our findings would not be generalizable to the crucially important subpopulation that they represent. Nonetheless, over half of this subgroup did not have outpatient commitment renewed once their initial orders expired and so were unexposed to outpatient commitment during much of the follow-up. Nonrenewal produced variation in length of time under outpatient commitment and its effect on victimization.

The second deviation from strict randomization was assignment of length of time of outpatient commitment, which varied as clinicians and courts applied the legal criteria for renewal of outpatient commitment. Not randomizing renewal could have led to the biased conclusion of attributing an intervention effect to subjects who might have been less likely to be victimized because of preexisting lower risk. This bias could only apply if subjects at higher risk of victimization were less likely to have their court orders renewed, but the legal criteria for outpatient commitment work in the opposite direction.

Although our analysis supports the hypothesis that outpatient commitment reduces victimization, four methodological factors probably led to an underestimation of this effect. 1) We measured only criminal victimization, not other types of victimization. 2) Subjects may have underreported criminal victimization because much of it occurred in domestic settings at the hands of family and friends (25). Such violence tends not to be reported as criminal assault (10, 13). 3) There is a greater likelihood of victimization among people who are violent (26), and the seriously violent subjects were all initially assigned to outpatient commitment. 4) There was differential attrition in our randomized groups by risk factors for victimization (lower nonadherence and higher insight among comparison subjects). These four factors tend to yield a conservative bias and likely lower the estimate of outpatient commitment’s effect on victimization.

|

|

|

Received Aug. 14, 2001; revision received Dec. 27, 2001; accepted April 10, 2002. From the Department of Sociology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; and the Department of Mental Health Law and Policy, University of South Florida, Tampa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hiday, Department of Sociology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-48103 and MH-51410 (University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill/Duke Program on Services Research for People With Severe Mental Disorders).

1. Hiday VA, Goodman RR: The least restrictive alternative to involuntary hospitalization, outpatient commitment: its use and effectiveness. J Psychiatry Law 1982; 10:81-96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hiday VA: Outpatient commitment: official coercion in the community, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996, pp 29-47Google Scholar

3. Hiday VA, Scheid-Cook TL: A follow-up of chronic patients committed to outpatient treatment. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:52-58Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, George L, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, Borum R, Wagner HR: Interpreting the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: a conceptual model. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1997; 25:5-16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Borum R, Hiday VA, Wagner HR, Burns BJ: Involuntary out-patient commitment and reduction of violent behavior in persons with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:324-331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Gerbasi JB, Bonnie RJ, Binder RL: Resource document on mandatory outpatient treatment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2000; 28:127-144Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hiday VA, Scheid-Cook TL: The North Carolina experience with outpatient commitment: a critical appraisal. Int J Law Psychiatry 1987; 10:215-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, Borum R: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1968-1975Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Appelbaum PS: Thinking carefully about outpatient commitment. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:347-350Link, Google Scholar

10. Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Drake RE: Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: prevalence, correlates, treatment and future research directions. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:685-696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:62-68Link, Google Scholar

12. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. J Ment Health Adm 1997; 24:152-165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cascardi M, Mueser KT, DeGiralomo J, Murrin M: Physical aggression against psychiatric inpatients by family members and partners. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:531-533Link, Google Scholar

14. Hiday VA: The social context of mental illness and violence. J Health Soc Behav 1995; 36:122-137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bloom JD, Mueser KT, Muller-Isberner R: Treatment implications of the antecedents of criminality and violence in schizophrenia and major affective disorders, in Violence Among the Mentally Ill: Effective Treatment and Management Strategies. Edited by Hodgins S. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer Academic, 2000, pp 145-169Google Scholar

16. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Ackerson TH, Alterman AI, Miles KM, Noordsy DL: Antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder and substance abuse in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:473-477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hiday VA: Coercion in civil commitment: process, preferences, and outcome. Int J Law Psychiatry 1992; 15:359-377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

19. McEvoy J, Apperson L, Appelbaum P, Ortlip P, Brecosky J, Hammill K, Geller JL, Roth L: Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:43-47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med 1983; 13:595-605Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766-771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Patterson DA, Lee M-S: Field trial of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale—Modified. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1386-1388Link, Google Scholar

23. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Criminal Victimization in the United States, 1992. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1994Google Scholar

24. Swanson JW, Borum R, Swartz MS, Hiday VA, Wagner HR, Burns BJ: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce arrests among persons with severe mental illness? Criminal Justice and Behavior 2001; 28:156-189Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR: Male-female differences in the setting and construction of violence among people with severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33(suppl 1):S68-S74Google Scholar

26. Allgulander C, Nilsson B: Victims of criminal homicide in Sweden: a matched case-control study of health and social risk factors among all 1,739 cases during 1978-1994. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:244-247Link, Google Scholar