Capacity to Provide Informed Consent for Participation in Schizophrenia and HIV Research

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The degree to which people with psychiatric symptoms and cognitive dysfunction can provide informed consent to participate in research is a controversial issue. This study was designed to examine the capacity of subjects with schizophrenia and subjects with HIV to provide informed consent for research participation and to determine the relationships among cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric symptoms, and decisional capacity. METHOD: Twenty-five men and women with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia and 25 men and women with HIV were recruited. The groups were compared in terms of neuropsychological functioning, psychiatric symptoms, and ability to provide informed consent to a hypothetical drug trial. RESULTS: Eighty percent of the subjects with schizophrenia and 96% of the HIV-positive subjects demonstrated adequate capacity to consent to the hypothetical drug trial, but subjects in the schizophrenia group had significantly lower scores on two of the four aspects of decisional capacity. For the subjects with schizophrenia, neuropsychological functioning and psychiatric symptoms (e.g., apathy and avolition), but not psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations and delusions), were significantly associated with decisional capacity. CONCLUSIONS: The majority of subjects who are recruited and willing to participate in schizophrenia or HIV research will have adequate capacity to provide consent. Cognitive dysfunction and the symptoms shown to be associated with impaired decisional capacity are not unique to schizophrenia and may occur with many other forms of illness. These findings underscore the importance of considering how decisional capacity will be assessed in all types of research, regardless of the specific condition being studied.

The degree to which individuals with psychiatric symptoms and impaired cognitive functioning are able to give informed consent for research participation is an important and controversial issue. Although it is generally agreed that informed consent procedures should provide adequate subject protection without placing unnecessary restriction on scientific advances, this concept is rather abstract and difficult to operationalize. What constitutes “adequate protection”? How does one define “unnecessary restriction”? Measured objectively, how vulnerable are these potential subjects?

In 1998, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission issued a report detailing 21 recommendations for conducting research on individuals with mental disorders that may affect decision-making capacity (1). Rather than resolving matters, this report has been criticized for many reasons (2), including focusing solely on psychiatric patients and diagnoses (3) while apparently ignoring the fact that decisional capacity can vary tremendously both within and across a wide range of psychiatric and general medical disorders (4). This focus on psychiatric illness may place overly stringent restrictions on mental health research and at the same time foster complacency among those conducting research on nonpsychiatric samples.

Schizophrenia research seems to have come under particularly close scrutiny during recent years, probably because of the belief that psychotic disorders are among the conditions most likely to render an individual incompetent relative to other forms of illness such as depression or vascular disease. This concern may have some validity, since several studies have found individuals with schizophrenia to have relatively impaired decision-making capacity when compared with various control groups. However, these studies have also shown that many people with schizophrenia are able to give informed consent (5, 6) and retain related information across time (7). Finally, there is recent evidence that individuals who have schizophrenia and lack adequate decision-making capacity may improve significantly with educational remediation (8).

Given that one’s diagnosis may imply relatively little about ability to provide informed consent, the question remains as to what factors are most informative regarding decisional capacity. In the current study, we sought to examine the decisional capacity of individuals with schizophrenia and those with HIV and to determine the degree to which factors such as cognitive functioning and severity of psychiatric symptoms affected this capacity. The selection of an HIV-positive subject group was based on the fact that, like those with schizophrenia, people with HIV are suffering an ongoing illness that can negatively affect both cognitive and psychiatric status, and these subjects are frequently invited to participate in research studies. Furthermore, it was expected that subjects with HIV would be demographically similar to those with schizophrenia in terms of age, education, and gender ratio.

Although we anticipated that the majority of subjects in both groups would demonstrate capacity for informed consent, we hypothesized that 1) subjects with schizophrenia would perform less well on measures of decision-making capacity than would those with HIV; and 2) both within and across groups, decision-making capacity would be strongly associated with level of cognitive functioning and moderately associated with severity of psychiatric symptoms.

Method

This study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent before participation after all procedures had been fully explained.

Subjects

All subjects were between the ages of 18 and 55 in order to avoid the confounding effects of aging. The first patient group consisted of 25 individuals (four women and 21 men; 17 inpatients and eight outpatients) who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia. These subjects were recruited from the Mental Health Clinical Research Center (N=21) and the inpatient psychiatry unit (N=4) at the University of Iowa. All available and potentially eligible subjects were invited to participate in the study, regardless of the severity of their illness, whether or not they had participated in previous research, or the apparent likelihood that they would be able to provide consent. Eighteen patients were receiving antipsychotic medication (novel antipsychotics: N=15; conventional antipsychotics: N=3); seven patients were receiving no antipsychotic treatment.

The second patient group consisted of 25 individuals who were HIV positive (six women and 19 men; one inpatient and 24 outpatients), had no history of psychotic disorder, and were recruited from the HIV Program in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Iowa. Fifteen subjects in the HIV-positive group had been diagnosed with AIDS, the median CD4 count at the time of the study was 366/mm3 (range=16–1562), and the median lowest ever known CD4 count was 124/mm3 (range=5–815). The normal CD4 range for a healthy adult is 263–2045/mm3; HIV-positive status and a CD4 count below 200/mm3 meets Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for an AIDS diagnosis. Twenty-two subjects were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy or were taking other HIV medications. Medical records revealed that eight had previously been diagnosed with major depressive disorder, two with dysthymic disorder, and one with social phobia. Fifteen were taking psychotropic medication, primarily antidepressants, at the time of study; none was taking antipsychotic medication.

Two subjects in the schizophrenia group and one in the HIV-positive group opted to withdraw from the study after their participation had begun. These three subjects were replaced. Five subjects with schizophrenia and three with HIV declined invitations to participate.

Assessment of Decisional Capacity

Each subject was asked to pretend that he or she was a potential candidate for a research study. Each subject then read, together with the examiner, a detailed informed consent form from a hypothetical 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a cognition-enhancing agent called Synaptoclear. The hypothetical study and its consent form were similar to those used in actual research and included multiple hospital visits and blood draws, physical examination, psychiatric and neuropsychological assessment, and other typical procedures; risks (including medication side effects); and benefits. The examiner then administered the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (9), a structured interview that was customized for the hypothetical study. This 21-item instrument allowed the examiner to rate, on a 3-point scale (0=inadequate, 1=partial, 2=adequate), four dimensions of the subject’s decisional capacity: understanding (13 items, score range=0–26), appreciation (three items, score range=0–6), reasoning (four items, score range=0–8), and ability to express a choice (one item, score range=0–2). The examiner also administered the Evaluation to Sign Consent (10), a much briefer questionnaire designed to assess the adequacy of subjects’ understanding of disclosed information. This is the instrument we currently use in our research and, unlike the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, the Evaluation to Sign Consent includes specific cutoffs to define adequacy of understanding of informed consent disclosures.

The Evaluation to Sign Consent was also used during the initial, actual consent process to determine whether subjects had an adequate understanding of the research, and none of them failed this assessment. It is important to note that the hypothetical drug study we developed was much more complex in its methods and potential risks and benefits than the actual informed consent research study in which the subjects were participating. Therefore, subjects who were able to provide informed consent to participate in the actual study were not necessarily able to do so within the context of the hypothetical study. In this manner, the potential confound of “studying only competent subjects” was minimized.

Neuropsychiatric Assessment

Form A of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (11) was administered to assess overall level of neuropsychological functioning and performance in five specific domains: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional ability, language, attention, and delayed memory. The reading subtest of the Wide-Range Achievement Test 3 (WRAT-3) (12) was administered to obtain a gross estimate of premorbid cognitive functioning. Finally, the Vocabulary, Letter-Number Sequencing, and Matrix Reasoning subtests from the WAIS-III (13) were administered to assess vocabulary skills, working memory, and reasoning/problem-solving, respectively.

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (14), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (15), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (16), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (17), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (18). The SANS and SAPS allowed for the specific assessment of negative symptoms (alogia, affective flattening, anhedonia/asociality, avolition/apathy), psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions), and disorganized symptoms (inappropriate affect, thought disorder, bizarre behavior).

Statistical Analyses

Demographic variables, neuropsychological scores, psychiatric symptom scores, and scores on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for the two patient groups were compared by using t tests; alpha level was set at 0.05. Within the schizophrenia group, scores of inpatients and outpatients on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool were also compared by using t tests; alpha level was set at 0.05.

To determine the overall association between psychiatric symptoms, neuropsychological functioning, and decisional capacity across both patient groups, three multiple regression analyses were conducted. In each of them, age and group were entered as the first block of independent variables, followed by a second block that included BPRS total score and total scale score on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Each of the three analyses had a single decisional capacity measure (understanding, appreciation, and, finally, reasoning) as the dependent variable. Subsequently, the groups were separated and these three regression analyses were conducted on each.

Last, relationships were examined among cognition, specific schizophrenia symptoms, and decisional capacity. This was accomplished by conducting age-controlled correlations among the following variables: total scale score and domain scores from the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status, the three WAIS-III subtest scores, the WRAT-3 reading scores, and scores on the decisional capacity measures of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool. Correlations were also calculated among SANS/SAPS variables and scores on the decisional capacity measures.

Results

The two groups were very similar in terms of education (schizophrenia group: mean=13.24 years, SD=2.61; HIV-positive group: mean=13.04 years, SD=2.11). The HIV-positive group was, on average, 5.84 years older than the schizophrenia group (schizophrenia group: mean=31.56 years, SD=9.77; HIV-positive group: mean=37.40 years, SD=7.76) (t=2.34, df=48, p<0.03), but age was not significantly correlated with any of the scores on the decisional capacity measures of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool.

With regard to the following results, it should be noted that higher scores indicate better functioning on the neuropsychological measures (Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status, WRAT-3, WAIS-III subtests) and the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, whereas lower scores indicate better functioning on the BPRS, SANS/SAPS, and Hamilton scales.

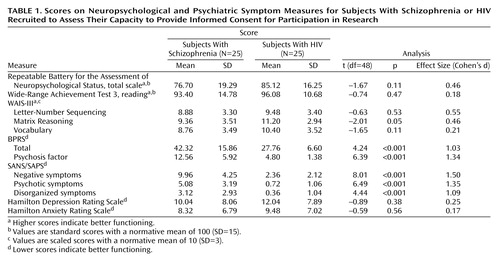

As shown in Table 1, the schizophrenia group performed more poorly than the HIV-positive group on almost all neuropsychological measures. Although effect sizes showed that group means differed by approximately 0.5 SD in overall neuropsychological functioning (Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status total scale score), working memory (Letter-Number Sequencing), and complex problem solving (Matrix Reasoning), these differences did not reach statistical significance. The schizophrenia group had higher mean scores on a measure of general psychiatric distress (BPRS), overall psychotic symptoms (BPRS psychosis factor), and on measures of negative, disorganized, and psychotic symptoms from the SANS/SAPS. Depression and anxiety scores were very similar between the groups.

On the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, schizophrenia subjects had lower mean scores than the HIV-positive group on all four elements of competency, but this reached statistical significance only for understanding and appreciation (Table 2). Within the schizophrenia group, there were no significant differences between inpatients and outpatients in scores on the decisional capacity measures. When assessed with the Evaluation to Sign Consent, 20 subjects (80%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.59–0.93) in the schizophrenia group and 24 subjects (96%; 95% CI=0.79–0.99) in the HIV-positive group demonstrated adequate understanding to provide consent to the hypothetical study. Five of the six subjects who “failed” the Evaluation to Sign Consent had understanding scores below 15, and the other scored exactly 15. The significance of this is elaborated in the Discussion section. An additional four subjects in the schizophrenia group and five in the HIV-positive group earned less than half of the possible points on the decisional capacity measures of appreciation or reasoning.

Across both groups, total scores for the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS together were associated with a significant amount of variance in the decisional capacity measures of understanding (R2 change=0.36; F=14.07, df=2, 45, p<0.001) and appreciation (R2 change=0.34; F=13.53, df=2, 45, p<0.001) when entered into the regression after age and illness had already been entered, but this was not the case with regard to reasoning (R2 change=0.08; F=2.07, df=2, 45, p<0.14). Partial correlations revealed that total scores for both the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS were significantly and independently associated with the decisional capacity measures of understanding and appreciation (Table 3).

When these analyses were conducted on the groups separately, results were much the same for the schizophrenia group. Specifically, total scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS were associated with a significant portion of variance in the decisional capacity measures of understanding (R2 change=0.45; F=9.05, df=2, 21, p=0.001) and appreciation (R2 change=0.49; F=10.63, df=2, 21, p=0.001) but not reasoning (R2 change=0.15; F=2.08, df=2, 21, p=0.15). Again, total scores for both the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS were significantly and independently associated with the decisional capacity measures of understanding (r=0.51, p<0.02, and r=–0.48, p<0.03, respectively) and appreciation (r=0.57, p=0.005, and r=–0.47, p<0.03). Pearson correlations among SANS/SAPS, neuropsychological, and MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool scores, controlling for age, are shown in Table 4.

In the HIV-positive group, total scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS were associated with MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool scores in the expected directions, but these associations did not reach statistical significance. Specifically, after we controlled for age, total scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status and the BPRS were associated with nearly 23% of the variance in the decisional capacity measure of understanding (R2 change=0.23; F=3.16, df=2, 21, p<0.07) and much smaller portions of variance for appreciation (R2 change=0.09; F=1.11, df=2, 21, p<0.35) and reasoning (R2 change=0.02; F=0.21, df=2, 21, p<0.82).

Discussion

The data presented here clearly support our first hypothesis and provide partial support for the second. As assessed by the Evaluation to Sign Consent, the vast majority of subjects in both the schizophrenia (80%) and the HIV-positive (96%) groups demonstrated adequate understanding to provide consent for the hypothetical research study. This is certainly an encouraging finding, made even more so by recently published data (8) suggesting that some or all of the subjects who failed the Evaluation to Sign Consent may have shown significantly improved performance if given a remedial intervention. As anticipated, the schizophrenia group did show weaker performance than the HIV-positive group on all four elements of decisional capacity, as measured by the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research. This difference reached statistical significance for the measures of understanding and appreciation but not for reasoning and ability to express a choice.

In the schizophrenia group, cognitive ability was found to be strongly associated with decisional capacity. Indeed, all 10 cognitive variables analyzed were significantly correlated with the decisional capacity measures of understanding and appreciation, and the WAIS-III Matrix Reasoning score was significantly correlated with the reasoning measure from the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool. This strong relationship is important to recognize, particularly because cognitive dysfunction is hardly unique to schizophrenia but occurs with many forms of psychiatric and general medical illness.

Analysis of specific schizophrenia symptoms and MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool scores clearly showed that negative and disorganized symptoms (e.g., avolition, apathy, inappropriate affect, etc.) were significantly associated with diminished decisional capacity, while psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions) were not. This may not be particularly surprising to schizophrenia researchers, given the evidence in the literature that negative and disorganized symptoms are more strongly related to cognitive functioning than are psychotic symptoms (19–23). However, the finding deserves emphasis, since people with schizophrenia may be viewed by the lay public as being completely out of touch with reality (8) because of the presence of hallucinations and delusions. This inaccurate impression could naturally lead to the false conclusion that most of these individuals are “incompetent.” Furthermore, like cognitive dysfunction, symptoms such as avolition, apathy, and anhedonia may be commonly seen in many other forms of illness. The fact that such symptoms are significantly related to decisional capacity underscores the fact that biomedical researchers need to be concerned about each subject’s capacity for informed consent, regardless of the specific patient population being studied.

With regard to the HIV-positive group, cognition and psychiatric symptom severity were correlated with decisional capacity in the expected directions, but these results did not reach statistical significance. This is most likely due to the fact that the HIV-positive group performed quite well on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, and the resulting range of values was somewhat restricted because of ceiling effects.

Across both groups, the six subjects who failed the Evaluation to Sign Consent were the same six who had the lowest scores (range=2–15) on the understanding measure of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool. Although there is no specific cutoff score for “incompetency,” a current National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored clinical trial (the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness [http://www.catie.unc.edu]) has stipulated that an understanding score below 15 indicates that a given subject is clearly in need of remediation. The fact that the Evaluation to Sign Consent identified such individuals raises the question of whether it is necessary for researchers to go to the effort of customizing the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool to their particular study and spending approximately 15 minutes on its administration when the briefer Evaluation to Sign Consent may provide them with similar results. The answer to this question lies in the fact that the Evaluation to Sign Consent assesses understanding of consent form information but not appreciation, reasoning, or the ability to express a choice. Administration of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool can guide the remediation process, since it provides the examiner with detailed information about all four of the specific elements of consent and which of these may be causing the subject difficulty. Furthermore, the goal of the consent process should not be to raise the subject to some minimal standard of competency but to provide information, assess the degree to which it is being adequately processed, and then to maximize this ability through further discussion and other remedial efforts on the basis of a given subject’s particular areas of difficulty. The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool is clearly more useful in such a process than the Evaluation to Sign Consent.

In addition to those subjects with scores of 15 or less on the understanding measure, an additional four subjects in the schizophrenia group and five in the HIV-positive group scored less than half of the possible points for the decisional capacity measures of appreciation and reasoning. As with the understanding domain, there are not specific cutoff scores for appreciation or reasoning to indicate what constitutes significant impairment. Nonetheless, earning less than half of the possible points in these domains should, at the very least, raise concern that a given subject may require remediation.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool scores of the schizophrenia group suggest that these subjects, on average, had adequate decisional capacity. It is noteworthy that these scores were considerably higher than those reported in a similar study conducted at the University of Maryland (8) and were, in fact, much more similar to the scores of the healthy comparison group in that study. It appears that there are several reasons for this. First, the schizophrenia group in our study was, on average, more than 8 years younger and had 1 more year of education than the group in the University of Maryland study. Second, the cognitive scores earned by our schizophrenia group were considerably higher than those in the University of Maryland study, with differences on several of the variables being approximately one normative standard deviation. Given their strong association, it would only follow that a group with higher cognitive scores would have higher MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool scores. Regarding psychiatric symptoms, in our study group BPRS total score was slightly lower, while BPRS psychosis factor score was slightly higher, although these differences were quite small. Finally, the presentation of consent form information must be considered. In the present study, the examiner, together with the subject, read through the hypothetical study consent form for approximately 15 minutes and then went through the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool structured interview, which involves detailed presentation, discussion, and questioning regarding all of the consent form information. Therefore, the subjects in the present study had an enriched exposure to the consent form information, which may be considered as a sort of pre-consent remediation.

A limitation of this study is that it did not include a remedial intervention and, thus, it cannot be determined how many of those few who performed poorly on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool and Evaluation to Sign Consent were potentially “competent.” Furthermore, each subject’s decisional capacity, cognition, and psychiatric symptoms were assessed within a 3-hour period. Ideally, both in research and clinical work, informed consent should be an ongoing process rather than a discrete event. It is also noteworthy that our subjects were obtained from a large research-oriented university hospital. While previous participation in research was not a consideration in sampling, it is likely that our subjects, as a group, had more experience with research participation than subjects in other settings. Finally, the use of a hypothetical study scenario raises the possibility that subjects behaved differently than they would have if being considered for a real drug trial. However, the benefits of being able to control consent form content and complexity through the creation of a hypothetical study were determined to outweigh the potential drawbacks of this method.

Taken together, our findings suggest that the majority of subjects who are recruited and willing to participate in schizophrenia or HIV research will have adequate capacity to provide consent, despite having serious forms of illness that affect cognitive and psychiatric status. Furthermore, the factors most strongly associated with impaired decisional capacity in the schizophrenia group were cognitive dysfunction and symptoms such as avolition and apathy, all of which can occur across a wide range of psychiatric and general medical conditions. This underscores the need for researchers to be concerned about each subject’s decisional capacity, regardless of his or her specific diagnosis. However, the extent to which additional procedures are indicated to ensure decision-making competence (e.g., formal assessment of capacity) will vary according to the likely impairment of each subject group as well as the degree of risk to which they are exposed (24).

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 22, 2001; revision received Jan. 10, 2002; accepted Feb. 26, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health Clinical Research Center, and the HIV Program, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa College of Medicine; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester. Address reprint requests to Dr. Moser, Department of Psychiatry, JPP2880, University of Iowa College of Medicine, 200 Hawkins Dr., Iowa City, IA 52240; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Nellie Ball Trust Research Fund to Dr. Moser. The authors thank Jack Stapleton, M.D., for his assistance with this study.

1. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity, volume I: Report and Recommendations of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, Dec 1998. http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/nbac/pubs.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. Carpenter WT, Vasi H: NBAC process and recommendations: a critique from clinician investigators. Biolaw 1999; 2:S412-S416Google Scholar

3. Carpenter WT, Conley RR: Sense and nonsense: an essay on schizophrenia research ethics. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:219-225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Oldham JM, Haimowitz S, Delano SJ: Protection of persons with mental disorders from research risk: a response to the report of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:688-693Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi, C: The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415-1419Link, Google Scholar

6. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: The MacArthur treatment competence study, III: abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:149-174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Mintz J: Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1508-1511Link, Google Scholar

8. Carpenter WT, Gold JM, Lahti AC, Queern CA, Conley RR, Bartko JJ, Kovnick J, Appelbaum PS: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:533-538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Sarasota, Fla, Professional Resource Press, 2001Google Scholar

10. DeRenzo EG, Conley RR, Love R: Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyond. J Health Care Law Policy 1998; 1:66-87Medline, Google Scholar

11. Randolph C: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1998Google Scholar

12. Wilkinson GS: Wide-Range Achievement Test 3: Administration Manual. Wilmington, Del, Wide Range, 1993Google Scholar

13. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Third Edition. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt), 1997Google Scholar

14. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50-55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799-812Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

18. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

19. O’Leary DS, Flaum M, Kesler ML, Flashman LA, Arndt S, Andreasen NC: Cognitive correlates of the negative, disorganized, and psychotic symptom dimensions of schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 12:4-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Bilder RM, Mukherjee S, Rieder RO: Symptomatic and neuropsychological components of defect states. Schizophr Bull 1985; 11:409-419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Liddle PF, Morris D: Schizophrenic syndromes and frontal lobe performance. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:340-345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Frith CD, Leary J, Cahill C, Johnstone EC: Performance on psychological tests: demographic and clinical correlates of these results. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1991; 13:26-29Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cuesta MJ, Peralta V: Cognitive disorders in the positive, negative and disorganization syndromes of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1995; 58:227-235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Appelbaum PS: Missing the boat: competence and consent in psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1486-1488Link, Google Scholar