Is Comorbidity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder Related to Greater Pathology and Impairment?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined whether patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have a more severe clinical profile than patients with either disorder without the other. METHOD: Outpatients with borderline personality disorder without PTSD (N=101), PTSD without borderline personality disorder (N=121), comorbid borderline personality disorder and PTSD (N=48), and major depression without PTSD or borderline personality disorder (N=469) were assessed with structured interviews for psychiatric disorders and for degree of impairment. RESULTS: Outpatients with diagnoses of comorbid borderline personality disorder and PTSD were not significantly different from outpatients with borderline personality disorder without PTSD, PTSD without borderline personality disorder, or major depression without PTSD or borderline personality disorder in severity of PTSD-related symptoms, borderline-related traits, or impairment. CONCLUSIONS: The additional diagnosis of PTSD or borderline personality disorder does little to augment the pathology or dysfunction of patients who have either disorder without the other.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and borderline personality disorder are DSM-IV diagnoses that are grounded independently in well-articulated theoretical and empirical frameworks. The more recent literature has suggested a possible relationship between these disorders. Comorbidity studies have shown a high frequency of PTSD among patients with borderline personality disorder (56%) (1) and a high frequency of borderline personality disorder among patients with PTSD (68%) (2). Among individuals in the community, it has been estimated that one-third of those with borderline personality disorder meet criteria for PTSD (3). In addition, it has been proposed that both disorders share a common pathogenesis, in that childhood sexual abuse has been found to have a strong association with both borderline personality disorder and PTSD (4, 5).

Trauma experts (e.g., Herman et al. [5]) have suggested that borderline personality disorder may be a complex variant of PTSD because many core borderline personality disorder features, such as affective instability, anger, dissociative symptoms, and impulsivity, are present in individuals with chronic PTSD. The concept that the effects of trauma can lead to personality disturbances is reflected in the provisional inclusion in the ICD-10 diagnostic system of the diagnosis of enduring personality changes after catastrophic stress.

A competing view is that the overlap between borderline personality disorder and PTSD is often the result of a premorbid borderline personality disorder, which increases vulnerability to the deleterious effects of trauma exposure (6). This view postulates that a distinction between the symptoms of PTSD and the traits of borderline personality disorder can be drawn on the basis of long-standing developmental processes. Thus, the literature suggests that PTSD and borderline personality disorder share common features but that there remains some controversy regarding the origins of these features. Additionally, there is limited knowledge regarding the impact of comorbid PTSD or borderline personality disorder on the clinical presentation of either disorder, despite the presumed link between borderline personality disorder and PTSD and the phenomenological interface between these disorders.

To our knowledge, only one study to date (7) has examined whether patients with a dual diagnosis of PTSD and borderline personality disorder represent a more impaired group than those with the single diagnosis of PTSD. In this study of female patients with PTSD and a history of childhood sexual abuse, no differences were found between women with and without borderline personality disorder in severity or frequency of PTSD symptoms, although the women with both disorders scored higher on measures of borderline traits (7). Limitations of this study include a small sample size and the lack of a comparison group of individuals with borderline personality disorder without PTSD.

To address some gaps in the literature, we present here a report from the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services project that examined whether the presence of a comorbid disorder (PTSD or borderline personality disorder) is associated with greater pathology and dysfunction than PTSD without borderline personality disorder or borderline personality disorder without PTSD. More specifically, we compared four groups of treatment-seeking outpatients (those with comorbid PTSD and borderline personality disorder, PTSD without borderline personality disorder, borderline personality disorder without PTSD, and major depression without PTSD or borderline personality disorder) along dimensions that are considered markers of borderline personality disorder and/or PTSD, as well as several other indices of impairment.

Method

Semistructured diagnostic interviews were administered to 1,500 outpatients seeking treatment at a general hospital private practice. Exclusion criteria for the study were age less than 18 years, a history of a developmental disability, or difficulty with the English language.

Trained diagnostic raters administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (8) and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (9). All raters achieved adequate interrater reliability before independently administering the interviews (10). The interrater kappa coefficient for 47 SCID-based PTSD diagnoses was 0.91.

Disorders were considered current if patients met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the disorder at the evaluation. The hospital’s institutional review committee approved the research protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Ninety participants were not given the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality and were excluded from the analyses. From the remaining 1,410 participants, 739 met criteria for one of the four targeted diagnostic groups and were included in the analyses: comorbid current PTSD and borderline personality disorder (N=48), borderline personality disorder without current PTSD (N=101), current PTSD without borderline personality disorder (N=121), and current major depression without current PTSD or borderline personality disorder (N=469).

Besides comparing the four groups on severity or frequency of PTSD symptoms and borderline personality disorder traits, we also examined whether a specific cluster of borderline personality disorder traits (affective instability, anger, dissociative symptoms, and impulsivity) identified by experts as characteristic of both disorders (5, 6) was more likely to be associated with borderline personality disorder than PTSD.

The four diagnostic groups were compared along several measures of impairment. Patients were interviewed about the number of times they had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons and history of suicide attempts. Items from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (11) were used to assess social and work impairment, including number of days out of work due to emotional or psychiatric problems and social functioning in the last 5 years.

Results

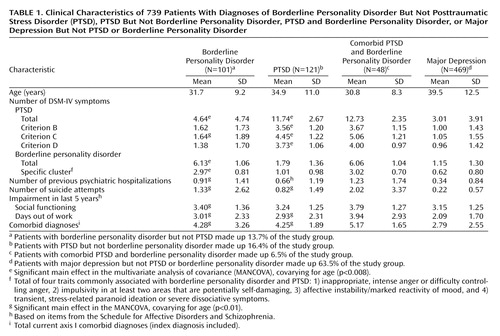

Most participants were women (N=497, 67.3%), white (N=638, 86.3%), unmarried (N=448, 60.6%), and had completed high school (N=594, 80.4%). The patients’ mean age was 37.1 (SD=12.1); mean age significantly differed among the groups (F=20.18, df=3, 738, p<0.001) (Table 1). There were no other significant demographic differences.

We analyzed our data as a two-by-two factorial design, with presence versus absence of borderline personality disorder and presence versus absence of PTSD as the grouping factors. We performed two multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs), covarying for age in both. In one MANCOVA, the dependent variables were symptoms/criteria of PTSD and borderline personality disorder traits, and in the other the dependent measures were indices of impairment.

The combined dependent variables (symptoms/criteria of PTSD and borderline personality disorder traits) were significantly affected by PTSD status (Wilks’s lambda=0.58, F=105.57, df=5, 730, p<0.001), borderline personality disorder status (Wilks’s lambda=0.37, F=245.96, df=5, 730, p<0.001), and their interaction (Wilks’s lambda=0.98, F=2.35, df=5, 730, p=0.04, controlling for age).

With a Bonferroni correction of 0.008, between-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted. The ANOVAs showed that no variables were significant for the interaction. Total number of PTSD symptoms and symptoms in each criterion of PTSD were significant for the PTSD without borderline personality disorder group, and total number of PTSD symptoms, criterion C symptoms, borderline personality disorder traits, and borderline personality disorder cluster traits were significant for the borderline personality disorder without PTSD group (Table 1).

When the impairment indices were used as dependent variables, controlling for age, the interaction was not significant (Wilks’s lambda=1.00, F=0.57, df=5, 728, p=0.73). Significant main effects were found for the PTSD without borderline personality disorder group (Wilks’s lambda=0.93, F=10.50, df=5, 728, p<0.001) and the borderline personality disorder without PTSD group (Wilks’s lambda=0.88, F=19.64, df=5, 728, p<0.001). Between-subjects analyses of covariance revealed that all variables except social functioning were significant for both groups, with a Bonferroni correction of 0.01 (Table 1).

A power analysis using an alpha level of 0.05 showed that, for a study group of 192, the power of 1.0, as defined by Cohen (12), was acceptable for a large effect to be detected.

Discussion

The present report found that outpatients with comorbid PTSD and borderline personality disorder did not have a more severe clinical profile than outpatients with PTSD without borderline personality disorder or those with borderline personality disorder without PTSD. More specifically, comorbidity of PTSD and borderline personality disorder was not significantly associated with greater or less severity of PTSD symptoms, borderline personality disorder traits, symptoms in each of the PTSD clusters, borderline personality disorder traits associated with PTSD and borderline personality disorder, or overall impairment.

Our findings confirm and expand on previous research showing that patients with comorbid PTSD and borderline personality disorder have a similar pattern of PTSD symptoms as those with PTSD and no borderline personality disorder (7). These results suggest that the additional diagnosis of PTSD or borderline personality disorder does little to exacerbate existing pathology or dysfunction. Perhaps there is little interaction between the clinical difficulties associated with each disorder; treatment that targets one disorder may not affect the other. Obviously, longitudinal, prospective research will elucidate whether these two disorders covary with one another.

The level of impairment found among the group of patients with comorbid PTSD and borderline personality disorder may have been unaffected by either diagnosis in this study because both disorders are chronic conditions that have severe effects on impairment (13, 14), and, therefore, the presence of a comorbid disorder did little to augment the level of existing dysfunction.

Another finding of this report was that patients with borderline personality disorder and PTSD reported a greater number of PTSD symptoms and criterion C symptoms (avoidant cluster) than PTSD patients without borderline personality disorder. A possible explanation for these findings is that PTSD has been conceptualized as a disorder of affect dysregulation (15), a prominent area of dysfunction among patients with borderline personality disorder (16). The avoidant cluster of PTSD incorporates dimensions that tap aspects of affect dysregulation and dissociation, such as restrictions in affect and in relationships, which play a principal role in borderline personality disorder.

In contrast, we found that PTSD patients without borderline personality disorder did not have higher levels of borderline personality disorder traits or traits related to both PTSD and borderline personality disorder than patients without PTSD, which suggests that associated features of PTSD may not include borderline traits, as previously postulated (5). Future research needs to examine the etiological role of childhood sexual abuse in PTSD and borderline personality disorder, since the negative sequelae of childhood sexual abuse are strongly associated with borderline personality disorder and PTSD (4, 5) and may account for the presence of PTSD symptoms among patients with borderline personality disorder.

|

Received July 12, 2001; revisions received Nov. 7, 2001, and May 10, 2002; accepted June 3, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University and Butler Hospital; and the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence. Address reprint requests to Dr. Zlotnick, Butler Hospital, 345 Blackstone Blvd., Providence, RI 02906; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-56404 and MH-48732 (Dr. Zimmerman).

1. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1733-1739Link, Google Scholar

2. Shea MT, Zlotnick C, Weisberg RB: Commonality and specificity of personality disorder profiles in subjects with trauma histories. J Personal Disord 1999; 13:199-210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Swartz M, Blazer D, George L, Winfield I: Estimating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in the community. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:257-272Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Rowan AB, Foy DW, Rodriguez N, Ryan S: Posttraumatic stress disorder in a clinical sample of adults sexually abused as children. Child Abuse Negl 1994; 182:145-150Google Scholar

5. Herman JL, van der Kolk BA: Traumatic antecedents of BPD, in Psychological Trauma. Edited by van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987, pp 111-126Google Scholar

6. Gunderson JG, Sabo AN: The phenomenological and conceptual interface between borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:19-27Link, Google Scholar

7. Heffernan K, Cloitre M: A comparison of posttraumatic stress disorder with and without borderline personality disorder among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: etiological and clinical characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:589-595Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

9. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

10. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:420-428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837-844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

13. Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Foa E, Kessler RC, McFarlane AC, Shalev AY: Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:60-65Medline, Google Scholar

14. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Oldham JM: Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:276-283Link, Google Scholar

15. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA: Disorders of Affect Regulation: Alexithymia in Medical and Psychiatric Illness. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1997Google Scholar

16. Linehan MM, Kehrer CA: Borderline personality disorder, in Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Barlow DH. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 396-441Google Scholar