Relationship of Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy With Criminal Arrest and Hospitalization for Substance Abuse in Male and Female Adult Offspring

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Maternal prenatal smoking has been found to be related to externalizing behavior problems in male offspring, but this relationship has rarely been examined in female offspring. Preliminary evidence suggests that maternal prenatal smoking may be particularly related to antisocial behavior outcomes in male offspring and substance abuse problems in female offspring. This study attempted to replicate these findings in a large-scale, longitudinal community cohort study. METHOD: Subjects were a birth cohort of 4,169 male and 3,943 female offspring born between 1959 and 1961 in Copenhagen, Denmark. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the subjects’ mothers self-reported the number of cigarettes smoked on a daily basis. When the offspring were adults, their criminal arrest histories and psychiatric hospitalizations for substance abuse were checked in national registers. Additional data were collected concerning maternal rejection of the infant, socioeconomic status, maternal age, pregnancy and delivery complications, use of drugs in pregnancy, paternal criminal history, and parental psychiatric hospitalization. RESULTS: Results indicate a dose-response relationship between the amount of maternal prenatal smoking and both criminal arrest and psychiatric hospitalization for substance abuse in male and female offspring. These relationships remained significant after potential demographic, parental, and perinatal risk confounds were controlled. Hospitalization of offspring for substance abuse mediated the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and criminal arrest for female but not for male offspring. CONCLUSIONS: Maternal prenatal smoking is related to criminal and substance abuse outcomes in male and female offspring. Higher rates of index arrests for female offspring may be related to their substance abuse problems.

Maternal prenatal smoking has been found to predict childhood externalizing problems, such as conduct disorder (1), delinquency (2), fighting (3), and hyperactivity (4). In addition, recent studies have linked maternal prenatal smoking to criminal offending by offspring in adulthood. Rantakallio and colleagues (2) found that male subjects whose mothers smoked during pregnancy were twice as likely as age-matched comparison subjects to have a criminal record at age 22. Similarly, an examination of the cohort that is the focus of the current study found a dose-dependent relationship between maternal smoking during the third trimester of pregnancy and arrests for violent and nonviolent crimes among male offspring. This relationship remained significant even after the analysis controlled for socioeconomic status, maternal rejection of the infant, maternal age, pregnancy and delivery complications, use of drugs during pregnancy, paternal criminal history, and parental psychiatric hospitalization (5).

The vast majority of studies of prenatal smoking and externalizing behavior problems of which we are aware (including our previous study) have focused exclusively on male offspring. We could find only four studies that examined the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and externalizing behavior problems separately for male and female offspring. These studies produced somewhat inconsistent results. For example, in their study of outcomes for toddler twins, Orlebeke and colleagues (6) found that the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and child externalizing behavior problems—particularly aggression—did not differ for boys and girls. Similarly, Gibson et al. (7) suggested that the effect size of the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and police contact with offspring was small to moderate for both genders. In contrast, a separate large-scale, prospective study (8) found that maternal prenatal smoking was related to adolescent conduct disorder and that this relationship was stronger for male than for female subjects. Although maternal prenatal smoking was initially found to be related to substance abuse outcomes in this study, the relationship was no longer significant when parental criminal history, parental substance abuse, child rearing practices, pregnancy problems, and demographic factors were controlled. Unfortunately this study did not report gender-specific tests of the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and child substance abuse.

In the only study we are aware of that examined both externalizing and substance abuse outcomes separately for male and female offspring, Weissman et al. (9) found that maternal prenatal smoking predicted conduct disorder in male but not in female offspring and predicted drug dependence in female but not in male offspring. The statistical control of parental psychiatric diagnoses (including antisocial personality disorder in the father), family risk factors, and a variety of pregnancy and delivery complications showed that these variables did not account for their findings. Unfortunately, the results of this study are somewhat limited by the use of retrospective reports of maternal smoking, the small size of the study group, and clinic-based selection of subjects.

The relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and antisocial behavior and substance abuse in female versus male offspring remains unclear. In an attempt to clarify this relationship, we examined the association between maternal prenatal smoking and both hospitalization for substance abuse and criminal arrests in male and female offspring in a cohort of 8,112 individuals born between 1959 and 1961 in Denmark. This sample is large and population-based, allowing for control of a variety of potential confounds. In addition, the mothers’ reports of smoking were collected during pregnancy, rather than through retrospective reports, and perinatal data were recorded in a detailed, reliable manner by neurologists and obstetricians.

Previous results in this area are mixed, but we hypothesize that maternal prenatal smoking will predict criminal arrests in male but not in female offspring. In addition, based on the findings of Weissman et al. (9), we hypothesize that maternal prenatal smoking will predict substance abuse in female but not in male offspring. Finally, we hypothesize that each of these relationships will remain significant despite control of potential confounds, including socioeconomic status, maternal rejection of the infant, maternal age, pregnancy and delivery complications, use of drugs during pregnancy, paternal criminal history, and parental psychiatric hospitalization.

Method

Subjects

Subjects in this study were 4,169 male and 3,943 female offspring drawn from a birth cohort of all individuals born between September 1, 1959, and December 31, 1961, at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark. Excluded from the sample were 93 male and 62 female offspring whose mothers did not provide a self-report of smoking behavior during the third trimester of pregnancy. The relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult criminal outcomes has been examined previously for the male offspring in this cohort (5).

Predictor Variables

Maternal prenatal smoking

In prenatal and postnatal interviews, the mothers reported the number of cigarettes smoked daily in their third trimester of pregnancy. The reported rates were typical of the general population of Denmark at that time.

On the basis of self-reports about the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the mothers were placed in one of the following categories: no cigarettes (N=2,042 male offspring; N=1,855 female offspring), one or two cigarettes (N=289 male offspring; N=287 female offspring), three to 10 cigarettes (N=1,206 male offspring; N=1,247 female offspring), or more than 10 cigarettes (N=632 male offspring; N=554 female offspring) smoked daily. In our previous study the final category was divided into two categories (11–19 cigarettes and 20 or more cigarettes); however, in this study the categories were collapsed to obtain adequate power to examine the potential dose-dependent relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and hospitalization of the offspring for substance abuse.

Maternal prenatal prescription drug use

Self-reports of drug use in pregnancy (scored as yes or no) were obtained from the mothers during prenatal and postnatal interviews at the hospital. The following types of drugs were included in this self-report: antihistamines, diuretics, antiepileptics, psychopharmacological drugs (including barbiturates), antibiotics, analgesics, and hormone treatments. The mothers were not asked about alcohol or illicit drug use during pregnancy.

Pregnancy and delivery complications

Obstetricians and their assistants recorded data about pregnancy and delivery complications during prenatal visits and at the time of the delivery at Rigshospitalet. Weighted pregnancy and delivery complications scales were then constructed by a team of American and Danish obstetricians and pediatric neurologists. The pregnancy complications scale included items such as bleeding or illness during pregnancy, use of radiation during pregnancy, and preeclampsia. The delivery complications scale contained items such as breech delivery, transverse position, forceps extraction, umbilical cord prolapse, and long birth duration.

Demographic factors

Maternal age (in years) at the time of the birth of the child was obtained from the records at Rigshospitalet. Information about socioeconomic status was obtained from an interview with the mother when the child was 1 year old. The socioeconomic classification was based on information about the breadwinner’s occupation, breadwinner’s education, type of income (wage/salary), and quality of housing. Enough data for classification of socioeconomic status were available for only 7,153 of the 8,112 participants in the study. As per the recommendation of Cohen and Cohen (10), missing data were recoded to the mean, and a dummy coded variable (1=socioeconomic data missing, 0=socioeconomic data present) was included as a statistical control in the logistic regression analyses.

Parental psychiatric hospitalization and criminal history

The father’s criminal history (present or absent) was assessed by checking arrests for index crimes recorded by the Danish criminal register in 1972. This register search was completed in the context of a study focused specifically on paternal risk factors, and therefore no criminal history data were available for the mothers. The parents’ psychiatric hospitalization history (present or absent) was assessed by checking the Danish Psychiatric Register of the Institute for Psychiatric Demography in August 1999. All hospitalizations for psychiatric illness, including substance abuse and dependence, are included in this register. The register provided data on discharge diagnoses according to the ICD system, with ICD-8 categories used through 1993 and ICD-10 categories used thereafter. Our analyses included statistical controls for parents’ psychiatric hospitalization history (present or absent), as well as parental psychiatric hospitalization for alcohol abuse or dependence (yes or no) and drug abuse or dependence (yes or no).

Maternal rejection

The mother’s rejection of the infant (high or low) was measured prenatally and when the child was 1 year old by means of data collected in interviews with the mother. This variable has been found to interact with delivery complications in the prediction of violent offending in this sample (11).

Offspring Outcome Variables

Criminal arrest

Offspring in the cohort were identified as either criminal (N=1,272 male offspring; N=396 female offspring) or noncriminal (N=2,897 male offspring; N=3,547 female offspring) on the basis of their index arrest histories. Arrest histories were obtained from the Danish criminal register in 1994. The following criminal index offenses were examined in this study: murder, attempted murder, robbery, rape, assault (including domestic assault), illegal possession of a weapon, theft, breaking and entering, fraud, forgery, blackmail, embezzlement, vandalism, prostitution, pimping, and narcotics offenses. (Inclusion or exclusion of narcotics offenses did not change the results in this study.) Because of the low number of female violent offenders, it was not possible to examine the effects of prenatal maternal smoking on arrests for violence for the female offspring in this cohort. Complete analyses of maternal prenatal smoking and violent criminal outcomes for the male offspring in this cohort have been published previously and are not repeated here (5).

Hospitalization for substance abuse

Offspring in the cohort were identified either as having a history of hospitalization for substance abuse (N=197 male offspring; N=93 female offspring) or not (N=3,972 male offspring; N=3,850 female offspring) on the basis of lifetime psychiatric hospitalization records obtained from the Institute for Psychiatric Demography in Aarhus, Denmark, in August 1999. Hospitalization for substance abuse was operationalized as the presence of any recorded hospitalization with the following ICD-8 or ICD-10 discharge diagnoses: psychoses due to alcohol or drugs, and alcohol/drug intoxication, withdrawal, abuse, or dependence.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed separately for male and female offspring. Bartholomew’s tests for order (trend tests) were used to examine the relationship between the amount of maternal smoking in pregnancy and the outcomes of arrest for index crimes and hospitalization for substance abuse (12). Logistic regression analyses were used to control for the potential confounds of socioeconomic status, maternal age, pregnancy and delivery complications, use of drugs in pregnancy, maternal rejection of the infant, paternal criminal history, and parental psychiatric hospitalization in the relationship between maternal smoking in pregnancy and offspring criminal and substance abuse outcomes. The alpha level was set at 0.05.

Results

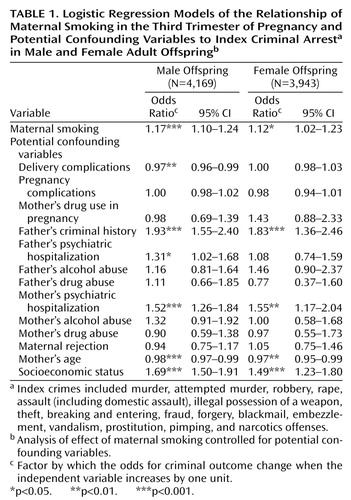

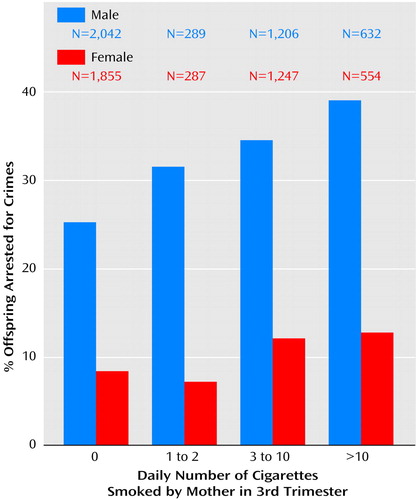

Offspring Criminal Outcome

As in previously published results (5), chi-square analyses revealed a significant relationship between the amount of maternal smoking in the third trimester of pregnancy and a history of criminal arrest in male offspring (Bartholomew χ2=59.86, df=3, N=4,169, p<0.001). There appears to be a dose-response relationship between index crime rates for male offspring and maternal prenatal smoking (Figure 1). The relationship between maternal smoking and criminal arrest in offspring was also significant for the female offspring in our sample (Bartholomew χ2=12.99, df=3, N=3,943, p<0.001). The percentage of female index offenders was positively related to the amount of cigarettes their mothers smoked on a daily basis in the third trimester of pregnancy, although the dose-response effect was somewhat less evident in female than in male offspring (Figure 1).

Logistic regression analyses revealed that the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and offspring criminal outcome remained significant when relevant demographic, parental, and perinatal risk confounds were controlled (males: χ2=25.50, df=1, N=4,169, p<0.0001; females: χ2=5.42, df=1, N=3,943, p<0.05) (Table 1). It is noteworthy that the odds ratios for the maternal smoking variable reflect the multiplicative increase in risk at each increasing level of amount smoked. Compared to male offspring whose mothers did not smoke during the third trimester, male offspring whose mothers smoked more than 10 cigarettes daily in the third trimester were 1.6 times (1.17×1.17×1.17) as likely to be arrested for an index crime. The respective odds ratio for female offspring was 1.4 (1.12×1.12×1.12).

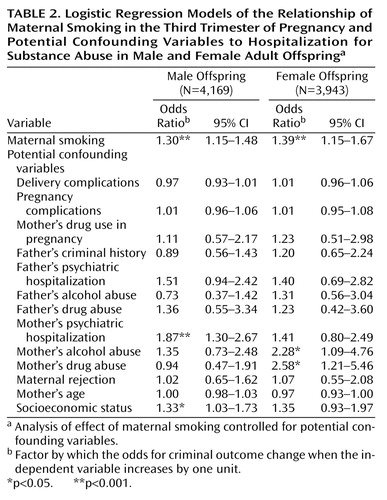

Offspring Substance Abuse Outcome

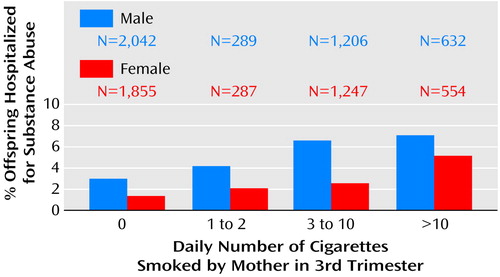

Chi-square analyses were also performed to test for a relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and hospitalization for substance abuse. Maternal smoking during the third trimester was related to higher rates of hospitalization for substance abuse in both male (Bartholomew χ2=32.44, df=3, N=4,169, p<0.001) and female offspring (Bartholomew χ2=27.30, df=3, N=3,943, p<0.001). There appeared to be a dose-response relationship between the amount of cigarettes the mother smoked and the rate of hospitalization for substance abuse in the offspring (Figure 2).

Logistic regression analyses also revealed that the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and offspring hospitalization for substance abuse remained significant when relevant demographic, parental, and perinatal risk confounds were controlled (males: χ2=17.44, df=1, N=4,169, p<0.0001; females: χ2=11.83, df=1, N=3,943, p<0.001) (Table 2). Compared to male offspring whose mothers did not smoke during the third trimester, male offspring whose mothers smoked more than 10 cigarettes daily in the third trimester were 2.2 times (1.30×1.30×1.30) as likely to be hospitalized for substance abuse. The respective odds ratio for female offspring was 2.7 (1.39×1.39×1.39).

Specificity of Substance Abuse Effect

We examined whether maternal prenatal smoking was related to offspring psychiatric hospitalization in general or whether this effect was specific to hospitalization for substance abuse. For these analyses we excluded data for the hospitalized individuals who had received substance abuse diagnoses. Logistic regression analyses were performed to test the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and psychiatric hospitalization (for non-substance-abuse-related diagnoses), controlling for relevant demographic, parental, and perinatal confounds. These results were nonsignificant for both male (χ2=0.37, df=1, N=3,944, p=0.54) and female offspring (χ2<0.01, df=1, N=3,829, p=0.97).

Offspring Criminal Arrest and Hospitalization for Substance Abuse

In this study, as in many others, criminal behavior and substance abuse were significantly related (male offspring: χ2=240.82, df=1, N=4,169, p<0.0001; female offspring: χ2=232.62, df=1, N=3,943, p<0.0001). Given this interrelationship, we explored whether criminal arrest would be related to maternal prenatal smoking when hospitalization for substance abuse was controlled and whether substance abuse would be related to maternal prenatal smoking when history of criminal arrest was controlled. These exploratory logistic regression analyses were undertaken while controlling for demographic, parental, and perinatal confounds. In both male and female offspring, maternal prenatal smoking was related to hospitalization for substance abuse when the analysis controlled for criminal arrest (male offspring: χ2=10.37, df=1, N=4,169, p<0.01; female offspring: χ2=8.48, df=1, N=3,943, p<0.01). In male offspring, but not in female offspring, maternal prenatal smoking was related to criminal arrest when the analysis controlled for hospitalization for substance abuse (male offspring: χ2=17.62, df=1, N=4,169, p<0.001; female offspring: χ2=2.61, df=1, N=3,943, p=0.11).

Discussion

The results of this study provided partial support for our gender-specific hypotheses concerning the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and offspring criminal and substance abuse outcomes. The relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and index criminal arrest was apparent for both male and female offspring. However, in female offspring this effect appeared to be explained by an increased risk for substance abuse outcomes, which, in turn, led to increased risk for arrest. The literature linking female criminal outcomes to maternal prenatal smoking is sparse. Our findings suggest that substance abuse should be considered as a potential mediator in any future examinations of this relationship.

Previously published findings on the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and externalizing behavior problems in female offspring have been mixed. Much of the research on aggression, conduct disorder, and crime in general has focused on male rather than female subjects. Researchers who have attempted to examine aggression in female subjects in more depth have noted that it may take a different form than aggression in male subjects (13). Specifically, female subjects may act aggressively through the manipulation of social and emotional relationships with others. This type of aggression would be less likely to lead to criminal arrest and would be better studied through peer reports or observational measures rather than official criminal records.

We found that maternal prenatal smoking was related to hospitalization for substance abuse for both male and female offspring. These relationships remained when demographic, perinatal, parental history, and offspring criminal history were controlled. This result contradicts the findings of other studies that have noted either that this relationship was no longer significant when relevant controls were applied (8) or that this relationship was specific to female offspring (9). Our measure of substance abuse differed from that used in both of these previous studies. We examined risk for substance abuse hospitalization through the age of 40, whereas the previous studies focused on adolescent outcomes. The children in the previous studies may not have passed through the age range for onset of substance abuse problems, and therefore relationships with potential risk factors such as maternal prenatal smoking may not have been fully assessed. Our study also used psychiatric hospitalization as a measure of substance abuse, whereas the others used interview measures. Our hospitalization measure captures only the subsample of individuals with the most severe substance abuse problems. These more severe substance abuse outcomes may be more specifically related to maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Such a finding would be consistent with what we noted about the relationship between male criminal offending and maternal prenatal smoking (5). We found that this relationship was apparent for more persistent records of offending and not for arrests limited to the adolescent years.

It does not appear that maternal smoking during pregnancy is related to increased risk for psychiatric hospitalization for disorders other than substance abuse. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have noted diagnosis-specific effects of maternal prenatal smoking (1, 8, 9).

Given the results of the research in this field, we believe there are several possible mechanisms or explanations for the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and offspring criminal and substance abuse outcomes. One possible explanation is that potential environmental or genetic confounds exist, but they have not been adequately assessed or controlled in the studies to date. As pointed out by Fergusson (14), the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and offspring antisocial outcomes could be accounted for by inherited genotypes passed down from the mother to the child. Although we controlled for paternal criminal history and parental hospitalization for substance abuse, our study could not fully assess potential contributing genetic factors.

Another potential confound that could not be controlled in our study was the teratogenic effect of the mother’s alcohol or illicit drug use during pregnancy. Data were not collected on these maternal behaviors because they were believed to be quite rare in Denmark at the time that this cohort was established. A recent study has suggested that maternal prenatal alcohol use may be a confound in this research area (15). It should be noted, however, that several other studies that have statistically controlled for maternal alcohol and illicit drug use in pregnancy have found that these variables do not account for the effects of maternal prenatal cigarette smoking on child outcomes (1, 4). Nevertheless, all of these studies used self-reports of maternal substance use; because of social desirability concerns, the mothers may have been more likely to report cigarette smoking than alcohol or illicit drug use. Therefore, we believe that the question of the potential confounding effects of maternal prenatal alcohol or illicit drug use on the relationship between maternal smoking and child antisocial outcome remains unanswered.

Maternal prenatal smoking may serve as a marker for other environmental effects that increase the risk of aggressive and substance abuse outcomes in children. For example, maternal prenatal smoking may be an indicator of a passive, neglectful parenting style. It may not reflect abuse or overt parental hostility but rather a subtle disruption in the parent-child relationship that in turn increases the risk for negative child outcomes. Controls for overt maternal rejection (the measure used as a control in this study) or overt parent-child discord (the measure used as a control in the study by Weissman et al. [9]) may be inadequate to account for this more subtle parenting effect.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may also be a marker of a stressful environment in general. Early environmental stressors can have a potent effect on the central nervous system of the developing child. In fact, nicotine exposure can also be considered an environmental stressor in itself. Such environmental stressors can affect the developing fetal and infant brain in a variety of ways (16). Specifically, animal studies have revealed that prenatal nicotine exposure is related to increased levels of testosterone in males, changes in serotonin receptor sites, and alterations in the vasopressin system. Of particular relevance to this study, these physiological changes have, in turn, been linked to aggressive behavior and substance abuse outcomes in animals and humans. Maternal cigarette smoking may set off a chain of transactional biological and environmental factors that act together to increase risk for deleterious child outcomes. Knowledge about these specific transactional processes will be useful in directing and implementing intervention or prevention programs aimed at reducing criminal behavior and substance abuse.

Our data were prospective in nature and did not rely on the mother’s retrospective reports of prenatal smoking obtained later in the life of the child. Nevertheless, our maternal self-report measure of smoking was limited in several respects. Specifically, it did not include information on specific nicotine doses, smoking during first and second trimesters, paternal smoking, or parental smoking after the birth of the child. Therefore, we were unable to complete more fine-grained analyses of the specific effects of nicotine, specific trimester effects, or the relative impact of prenatal versus postnatal exposure to maternal smoking. It should be noted that the Weissman study found that the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and adolescent conduct disorder and substance dependence remained significant when maternal postnatal smoking was controlled. In addition, an Australian cohort study with measures of maternal smoking during pregnancy and during the postnatal period found that prenatal, rather than postnatal, smoking was the best predictor of child externalizing behavior problems (17).

Not all children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy will become criminals or substance abusers. In fact, our results suggest that the vast majority of these children will not be arrested or admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Future studies aimed at assessing the potential protective factors in this process would also be useful in designing prevention and intervention programs. A public health approach to criminal behavior and substance abuse calls for prevention and intervention strategies designed to reduce the known risk factors for these outcomes. Smoking cessation programs for pregnant women (18), even low-intensity counseling interventions by general practitioners (19), have been found to reduce or eliminate maternal smoking during pregnancy. Our study suggests that prenatal smoking cessation programs may have the potential to reduce not only negative physical health outcomes, but also negative behavioral health outcomes, in future generations of children.

|

|

Received Jan. 17, 2001; revisions received June 15 and Aug. 6, 2001; accepted Aug. 16, 2001. From Emory University; Institute of Preventive Medicine, Copenhagen; and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Address reprint request to Dr. Brennan, Department of Psychology, Emory University, 532 N. Kilgo Cir., Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). This article was completed during the first author’s fellowship year at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, Calif., with financial support provided by grant 034 248 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and NIH grant BCS 960 1236. This research was also supported by an NIH Research Scientist Award (Dr. Mednick) and Danish Research Council grant 9700093 and the National Board of Health grant 1406/2-4-1997 (Dr. Mortensen).

Figure 1. Rates of Index Criminal Arresta in Male and Female Adult Offspring, by the Number of Cigarettes Smoked Per Day by Mothers in the Third Trimester of Pregnancy

aIndex crimes included murder, attempted murder, robbery, rape, assault (including domestic assault), illegal possession of a weapon, theft, breaking and entering, fraud, forgery, blackmail, embezzlement, vandalism, prostitution, pimping, and narcotics offenses.

Figure 2. Rates of Hospitalization for Substance Abuse in Male and Female Adult Offspring, by the Number of Cigarettes Smoked Per Day by Mothers in the Third Trimester of Pregnancy

1. Wakschlag LS, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Green SM, Gordon R, Leventhal BL: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of conduct disorder in boys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:670-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rantakallio P, Laara E, Isohanni M, Moilanen I: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and delinquency of the offspring: an association without causation? Int J Epidemiol 1992; 21:1106-1113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bagley C: Maternal smoking and deviant behaviour in 16-year-olds: a personality hypothesis. Pers Individ Dif 1992; 13:377-378Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A: Maternal smoking and behavioral problems of children. Pediatrics 1992; 90:342-349Medline, Google Scholar

5. Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mednick S: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult male criminal outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:215-219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Orlebeke JF, Knol DL, Verhulst FC: Increase in child behavior problems resulting from maternal smoking during pregnancy. Arch Environ Health 1997; 52:317-321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Gibson CL, Piquero AR, Tibbetts SG: Assessing the relationship between maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and age at first police contact. Justice Q 2000; 17:519-542Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood J: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:721-727Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne PJ, Kandel DB: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychopathology in offspring followed to adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:892-899Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cohen J, Cohen P: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1975Google Scholar

11. Raine A, Brennan PA, Mednick SA: Birth complications combined with early maternal rejection at age 1 year predispose to violent crime at age 18 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:984-988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fleiss JL: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1981Google Scholar

13. Crick NR, Grotpeter JK: Relational aggression, gender and social psychological adjustment. Child Dev 1995; 66:710-722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fergusson DM: Prenatal smoking and antisocial behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:223-224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hill SY, Lowers L, Locke-Wellman J, Shen SA: Maternal smoking and drinking during pregnancy and the risk for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. J Stud Alcohol 2000; 61:661-668Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. King JA: Perinatal stress and impairment of the stress response: possible link to nonoptimal behavior. Ann NY Acad Sci 1996; 794:104-112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Williams GM, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Bor W, Andersen MJ, Richards D: Maternal cigarette smoking and child psychiatric morbidity: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics 1998; 102:e11Google Scholar

18. Ford RP, Cowan SF, Schluter PJ, Richardson AK, Wells JE: SmokeChange for changing smoking in pregnancy. NZ Med J 2001; 114:107-110Medline, Google Scholar

19. Melvin CL, Dolan-Mullen P, Windsor RA, Whiteside HP, Goldenberg RL: Recommended cessation counseling for pregnant women who smoke: a review of the evidence. Tob Control 2000; 9:11180-11184Google Scholar