MRI Assessment of Children With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder or Tics Associated With Streptococcal Infection

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed selective basal ganglia involvement in a subgroup of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or tics believed to be associated with streptococcal infection. METHOD: Using computer-assisted morphometric techniques, they analyzed the cerebral magnetic resonance images of 34 children with presumed streptococcus-associated OCD and/or tics and 82 healthy comparison children who were matched for age and sex. RESULTS: The average sizes of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus, but not of the thalamus or total cerebrum, were significantly greater in the group of children with streptococcus-associated OCD and/or tics than in the healthy children. The differences were similar to those found previously for subjects with Sydenham’s chorea compared with normal subjects. CONCLUSIONS: These results support the hypothesis that there is a distinct subgroup of subjects with OCD and/or tics who have enlarged basal ganglia. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis of an autoimmune response to streptococcal infection.

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) occur in a newly described subgroup of children who are hypothesized to develop obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or tic disorders, or have symptom exacerbations, following infection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (1). A proposed pathophysiology is that antibodies directed toward the group A beta-hemolytic streptococci bacteria cross-react with the basal ganglia of genetically susceptible hosts, leading to OCD and/or tics.

A single case study of an adolescent with PANDAS showed a relationship among basal ganglia size, symptom severity, and treatment with plasmapheresis (2) and led to the present investigation. We compared the cerebral magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of 34 children in whom we found an apparent relationship between neuropsychiatric symptom exacerbations and streptococcal infection with those of 82 healthy comparison children.

METHOD

For the clinical group, children with acute-onset or striking exacerbations of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and/or tics were sought through national recruitment. No mention of an infectious trigger was included in the advertisements. Screening evaluations were conducted by at least two physicians and included a clinical interview of the child and parents and a review of the child’s medical records. Children with a history of Sydenham’s chorea, rheumatic fever, an autoimmune disorder, or a cardiac examination consistent with previous rheumatic carditis were excluded from study.

From 270 telephone screening interviews and 109 in-person screening interviews, 50 children met criteria for membership in the PANDAS subgroup; these 50 children have been described previously (1). Forty received at least one MRI scan, and 34 of these were of sufficient quality to permit basal ganglia quantification. These scans serve as the basis for this report. There were 24 boys and 10 girls in this clinical group; 18 had a primary diagnosis of OCD, and 16 had a primary diagnosis of a tic disorder. Thirty subjects had some obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and 25 had some motor tics.

For all participants, written assent from the child and consent from the parents were obtained. The protocols were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Institutional Review Board.

Based on age and sex, 82 comparison subjects were chosen from a group of 186 healthy children participating in an ongoing study of brain development being conducted by the Child Psychiatry Branch of NIMH. Details of the screening process and exclusion criteria for this group, in which only one of six initial contacts was accepted for the study, have been presented elsewhere (3).

All children were scanned on the same General Electric 1.5-tesla Signa scanner with the same imaging sequences (three-dimensional spoiled gradient recalled echo in the steady state imaging, echo time=5 msec, time to repeat=24 msec, flip angle=45˚, acquisition matrix=192 × 256, number of excitations=1, and field of view=24 cm). T1-weighted images with slice thickness of 1.5 mm in the axial plane and 2.0 mm in the coronal plane were obtained.

Children were scanned in the evening to promote their falling asleep during the scan. Younger children were allowed to bring blankets or stuffed animals into the scanner and have their parents read to them. No sedation was used for comparison subjects. Ten children with PANDAS required sedation with oral lorazepam (2 mg) or chloral hydrate (2 g).

All scans were judged clinically unremarkable by a neuroradiologist. Images were analyzed blind to any subject characteristics. Total cerebral volume was quantified by using a semiautomated technique that models the brain as an active surface template, which then conforms to the individual brain through a series of energy minimization functions (4). Quantifications of the caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, and thalamus were done by hand tracing as described previously (3). Thalamic area was obtained from a single mid-sagittal slice because we were not able to obtain reliable measures of thalamic volume.

Intraclass correlation coefficients were used to assess intrarater reliability of measurements. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with diagnosis as a between-subjects factor was used to assess group differences in age, caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus, and total brain volume. Group differences in symmetry of these structures were assessed with a repeated measure ANOVA in which diagnosis was a between-subjects factor and side (left versus right) was a within-subject factor and the significance of the diagnosis-by-side interaction was assessed.

RESULTS

Intraclass correlations (ICCs) of intrarater reliability were as follows: caudate ICC=0.85, putamen ICC=0.82, globus pallidus ICC=0.80, thalamus ICC=0.78, total brain volume ICC=0.99.

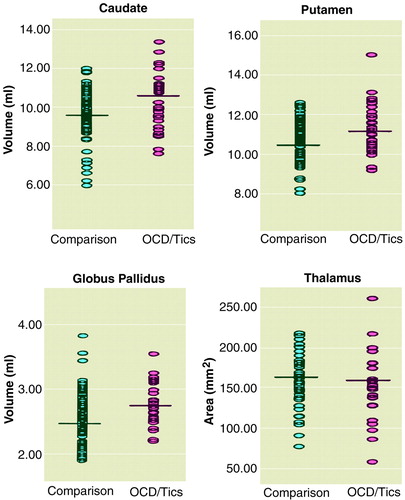

Average sizes of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus were all larger in the PANDAS group than in the comparison group. The mean caudate volume in the children with PANDAS was 10.5 ml (SD=1.4), compared with 9.8 ml (SD=1.2) in the healthy children (F=8.7, df=1, 114, p=0.004). The mean putamen volume in the children with PANDAS was 11.2 ml (SD=1.2), compared with 10.8 ml (SD=0.91) for the healthy children (F=6.2, df=1, 114, p=0.02). The mean globus pallidus volume in the children with PANDAS was 2.8 ml (SD=0.3), compared with 2.6 ml (SD=0.4) in the healthy children (F=6.1, df=1, 114, p=0.02) (figure 1). Mean differences were approximately 8% for the caudate, 5% for the putamen, and 7% for the globus pallidus. In contrast, there were no significant differences between groups in the thalamic area or total brain volume. The mean thalamic area volume of the children with PANDAS was 153.2 mm2 (SD=41.6), compared with 156.5 mm2 (SD=32.9) in the healthy children (F=0.1, df=1, 114, p=0.72). The mean total brain volume of the children with PANDAS was 1158.4 ml (SD=146.9), compared with 1145.9 ml (SD=109.9) for the healthy children (F=0.14, df=1, 114, p=0.71).

In the group of children with PANDAS, there were no significant correlations between basal ganglia size and symptom severity or duration between onset of symptoms and scan. There were also no differences in basal ganglia size between the children with a primary diagnosis of OCD and those with a tic disorder. There were no diagnosis-by-side (left versus right) interactions for any of the structures examined.

DISCUSSION

The basal ganglia enlargements we found among the children with PANDAS are similar those found in patients with Sydenham’s chorea (5) and are consistent with a hypothesis of a selective cross-reactive antibody-mediated inflammation of the basal ganglia underlying the development of poststreptococcal OCD or tics in some individuals. However, as in Sydenham’s chorea, the lack of correlation between basal ganglia size and symptom severity indicates that the relationship between basal ganglia size and pathophysiology is not direct.

Because of poor sensitivity and specificity of the MRI findings, an MRI scan is not warranted for the diagnosis or clinical monitoring of children with poststreptococcal OCD or tics.

Received Aug. 10, 1998; revision received May 27, 1999; accepted June 4, 1999. From the Child Psychiatry and Pediatrics and Developmental Neuropsychiatry Branch of NIMH. Address reprint requests to Dr. Giedd, Child Psychiatry Branch, NIMH, 10 Center Dr., MSC 1367, Bldg. 10, Rm. 4C110, Bethesda, MD 20892-1600; [email protected] (e-mail)

figure 1. Scatterplots of Basal Ganglia Volume and Thalamus Area of 34 Children With Poststreptococcal OCD or Tics and 82 Healthy Comparison Children Matched for Age and Sex

1. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perlmutter S, Lougee L, Dow S, Zamkoff J, Dubbert BK: Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:264–271Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Leonard HL, Richter D, Swedo SE: Case study: acute basal ganglia enlargement and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in an adolescent boy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:913–915Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Giedd JN, Snell JW, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Casey BJ, Kozuch PL, Vaituzis AC, Vauss YC, Hamburger SD, Kaysen D, Rapoport JL: Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of human brain development: ages 4–18. Cereb Cortex 1996; 6:551–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Snell JW, Merickel MB, Ortega JM, Goble JC, Brookeman JR, Kassell NF: Model-based boundary estimation of complex objects using hierarchical active surface templates. Pattern Recognition 1995; 28:1599–1609Google Scholar

5. Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Kruesi MJP, Parker C, Schapiro MB, Allen AJ, Leonard HL, Kaysen D, Dickstein DP, Marsh WL, Kozuch PL, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger S, Swedo SE: Sydenham’s chorea: magnetic resonance imaging of the basal ganglia. Neurology 1995, 45:2199–2202Google Scholar