Adult Outcomes of Child- and Adolescent-Onset Schizophrenia: Diagnostic Stability and Predictive Validity

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The goal of the study was to establish the predictive validity of a diagnosis of schizophrenia in childhood and early adolescence by examining diagnostic continuity into adult life and comparing social and symptomatic outcomes of child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia with those of nonschizophrenic psychoses. METHOD: A total of 110 consecutive patients with first-episode child- or adolescent-onset psychosis (mean age at onset=14.2 years) presenting to the Maudsley Hospital in London between 1973 and 1991 were followed up an average of 11.5 years after first contact. Ninety-three (84.5%) of 110 patients were successfully followed-up, 51 with a first-episode diagnosis of DSM-III-R schizophrenia and 42 with nonschizophrenic psychoses. Consensus best-estimate DSM-III-R diagnoses were made at follow-up, and course and outcome were assessed blind to first-episode diagnosis. RESULTS: Diagnostic stability was high for child- and adolescent-onset DSM-III-R schizophrenia (positive predictive value=80%) and affective psychoses (positive predictive value=83%) but much lower for schizoaffective and atypical psychoses. Compared with other psychoses, child- or adolescent-onset schizophrenia was associated with significantly worse symptomatic and social outcomes, which were characterized by a chronic illness course and severe impairments in social relationships and independent living. CONCLUSIONS: The diagnosis of DSM-III-R schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence has good predictive validity. The high level of diagnostic stability suggests etiological continuity with adult schizophrenia, with onset in childhood and adolescence associated with a particularly malignant course and outcome.

Since the publication of DSM-III in 1980, schizophrenia has been diagnosed in children and adolescents by using unmodified “adult” criteria. Although compelling evidence suggests that schizophrenia can be reliably identified in children as young as age 7 by using adult diagnostic criteria (1, 2), there remains uncertainty about the diagnostic stability and predictive validity of schizophrenia in childhood and early adolescence. Misdiagnosis may occur because the symptoms of other disorders overlap with schizophrenia. Affective psychoses (3–6) and developmental disorders with psychotic episodes (2, 7) can mimic schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence leading to false-positive diagnostic errors. Developmental variation could also mean that phenotypic variants of schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence may be missed by adult diagnostic criteria leading to false-negative diagnostic errors (7).

In the absence of specific biological markers, careful longitudinal follow-up remains a crucial method for determining the validity of psychiatric diagnoses. Robins and Guze (8) included outcome and stability of diagnosis over time as two of the five criteria for establishing diagnostic validity. Kraepelin distinguished the poor outcome of dementia praecox from the more benign outcome and episodic course of manic-depressive psychosis. Evidence of diagnostic stability is also important for validation because it is likely to reflect a stable underlying psychopathological process (9). In adults, definitions of schizophrenia that include duration criteria (e.g., DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and Feighner criteria) have higher levels of diagnostic stability (10, 11) and better predictive validity (11–14) than definitions of schizophrenia based on Schneiderian first-rank symptoms.

There is a widely held view that a valid diagnostic distinction cannot be made between schizophrenia and affective psychosis in childhood and adolescence. This view has been supported by several follow-up studies of child-and adolescent-onset psychoses showing a high degree of diagnostic instability (6, 15). In a study of patients who presented both as children and adults to the Maudsley Hospital in London, adolescents with a diagnosis of affective psychosis were just as likely to receive an adult diagnosis of schizophrenia as those who were first described as having schizophrenia were to follow a bipolar course (15). Werry et al. (6) examined the stability of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a follow-up study of adolescent-onset psychoses and found that 25% of first-episode diagnoses of schizophrenia were changed to bipolar disorder after 5 years and 50% of patients with bipolar disorder were initially diagnosed as having schizophrenia. A recent follow-up study of DSM-IV-defined adolescent-onset schizophrenia and affective psychoses found a higher degree of diagnostic stability with 90% diagnostic agreement over a 2-year period, although follow-up assessment was not blind to the initial diagnosis (16).

To establish predictive validity and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, follow-up studies of child- and adolescent-onset psychoses must include a nonschizophrenia comparison group. There is a lack of consensus among the few studies that meet this criterion, with some reporting no differences in outcome between schizophrenia and affective psychoses (17, 18) and others suggesting a poorer outcome for schizophrenia compared to other psychoses (19, 20). These later studies have significant methodological limitations, including a low follow-up rate (19) and outcome comparisons made on the basis of adult follow-up diagnoses rather than the first-episode diagnoses (20). Hence, inconsistent findings, together with important methodological limitations, make it very difficult to draw any secure conclusions about the diagnostic stability and predictive validity of child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia.

The purpose of the study reported here was to test the predictive validity of DSM-III-R schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence by examining whether the diagnosis showed stability into adult life and predicted a worse outcome compared to other psychoses. The design aimed to avoid the methodological limitations that have beset previous follow-up studies of psychoses in this age group. Although the age at onset of psychosis in the followed-up sample ranged from 10 to 17 years, the shorthand term “adolescent-onset” will be used here. Fifty-one patients with DSM-III-R schizophrenia and 42 with nonschizophrenic psychoses were retrospectively ascertained and followed up in adult life an average of 11 years after their first psychotic episode. The primary outcomes of the study were indices of diagnostic stability (sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio, and positive predictive value) and measures of social disability and symptomatic functioning in adult life.

Method

Subjects

Initial psychosis screen

A retrospective psychosis screen was applied to the records of all patients under 18 years of age who had attended the Maudsley Hospital in South London between 1973 and 1991. At the Maudsley Hospital Children’s Department, data from clinical assessments are combined through standard coding of specified symptoms, and the symptom codes are recorded on standardized clinical data summaries (“item sheets”) and stored on a computer (21). Item sheets were completed on more than 95% of all patients during the study period, during which the format of the item sheets remained constant. Patients who screened positive for psychosis were identified from the item sheets if at least one of the following criteria were met: 1) an ICD-9 diagnosis of schizophrenia (295.0–295.9), affective psychosis (296.0–296.9), paranoid state (297.0–297.9), or other nonorganic psychosis (298.0–298.9) (equivalent ICD-8 codes were used from 1973 to 1977), or 2) one or more of the symptoms of hallucinations, delusions, or ideas of reference was definitely present. Patients attending the Maudsley Hospital Adult Department were also included in the screened-positive group if they were under age 18 at the baseline assessment and had an ICD-9 psychotic diagnosis (ICD-8 codes were used from 1973 to 1977). A total of 196 patients screened positive for psychosis.

Baseline study group

At the second stage of the study, a detailed chart review was conducted for the 196 screened-positive patients. The selection criterion was unequivocal evidence of one or more of the following Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) psychotic symptoms (22) occurring in clear consciousness and lasting for at least 2 weeks: prominent hallucinations, delusions, or incoherence/loosening of associations. The records of 23 of the initial 196 patients who screened positive had missing case notes or not enough clinical details to confidently determine the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms, 58 patients were confirmed as nonpsychotic after their case records were examined, and five had a diagnosis of autism in the absence of an RDC psychotic symptom. The remaining 110 patients constituted the baseline adolescent-onset psychosis sample and were eligible for follow-up.

Success of the follow-up

Adequate follow-up data were obtained on 93 (84.5%) of the 110 patients over a 2-year period. These 93 patients will be referred to as the followed-up sample. Subjects were located by using a variety of methods, including searches of the U.K. National Health Service Central Register and records of local U.K. Family Health Service Authorities. Information recorded in the patients’ medical records at the first admission was also used to contact subjects’ parents, family doctors, and consultant psychiatrists. After subjects had been traced, they received a letter introducing the study. Finally, subjects were visited by the author to explain the purposes of the study and to seek their consent. After complete description of the study to subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Seventeen subjects (15.4%) were excluded from the final followed-up sample because of inadequate data. Seven subjects refused to be interviewed, and sufficient clinical information for these subjects was not available from other sources. Four subjects could not be traced, and nine had died. However, for three of the deceased subjects, there were enough detailed clinical data to include them in the followed-up sample. Seventy-four (80%) of the followed-up sample were assessed in face-to-face interviews. For a further 19 subjects, high-quality information was available from relatives, professionals, and case records. There were no significant differences between the followed-up sample (N=93) and those not followed-up (N=17) in age at onset, gender, ethnicity, place of residence, and DSM-III-R baseline diagnoses.

Adolescent Baseline Assessment

Procedure

Baseline information was extracted from patients’ medical records by using a structured coding procedure specifically designed for the study. The quality of case note information recorded by Maudsley Hospital psychiatry trainees was uniformly high and followed the guidelines on obtaining and recording clinical information produced by the Maudsley Hospital and Institute of Psychiatry. To minimize potential bias and to avoid inferential impressions, items were rated only if the case notes contained explicit positive statements concerning the patient’s status. All baseline ratings were made blind to adult outcome status. The mean age of subjects at baseline assessment was 14.9 years (SD=1.5, range=11–17). The mean duration from onset of psychotic symptoms to baseline assessment was 5.3 months (SD=7.1, range=0.2–36).

Measures

Data on psychopathological characteristics at baseline from medical records were rated by using the OPCRIT checklist for psychotic illness, version 3.31 (23). OPCRIT comprises a checklist of 90 items constructed from operational criteria for the major psychiatric classifications (ICD, RDC, DSM-III-R, etc.) and a suite of computer programs that allows psychopathological data to be entered and edited and diagnoses to be generated according to each set of diagnostic criteria. OPCRIT has been shown to have good reliability for DSM-III-R diagnoses made by using the 90-item checklist (kappa=0.73) (24). The concurrent validity of OPCRIT DSM-III-R diagnoses has been established in analyses showing good to excellent agreement with consensus best-estimate diagnoses (25).

Of the 93 subjects in the followed-up sample, 51 (55%) had a DSM-III-R diagnosis (OPCRIT derived) of schizophrenia at baseline, 12 (13%) had a schizoaffective psychosis, 23 (25%) had an affective psychosis (unipolar major depressive and bipolar psychoses), and seven (8%) had an atypical psychosis (unspecified functional psychosis). Data for all patients with nonschizophrenic psychoses (N=42) were combined for further analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 51 patients with schizophrenia and the 42 patients with nonschizophrenic psychoses. Both groups were similar in age at onset, duration of follow-up, gender ratio, referral source (local area versus elsewhere), socioeconomic status, and ethnicity.

Adult Follow-Up Assessment

Procedure

All assessments were done by raters who were blind to baseline diagnosis, as the OPCRIT data were not analyzed until all follow-up interviews had been completed. Although the main emphasis in the adult follow-up assessment was on direct interviewing of subjects, where possible multiple sources of information (medical records and interviews with health professionals and relatives) were used to corroborate or supplement information from subject interviews. A median of two sources of information was obtained per subject. After all available sources of information were combined, adult best-estimate DSM-III-R diagnoses were made. The mean length of follow-up (time from baseline) for the 93 subjects in the followed-up sample was 11.5 years (SD=5.2, range=4–22). The mean age at follow-up assessment for the sample was 27.2 years (SD=5.2, range=17–39).

Measures

Interviews to determine adult lifetime diagnosis were conducted with a modified version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (26). Coverage was broadened to include diagnoses not covered in the original schedule (27) and some additional questions specifying precise DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for psychoses. The author, who conducted the SADS-L interviews, obtained training from experienced interviewers at the Institute of Psychiatry.

Although no “gold standard” exists to measure lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, the currently accepted standard procedure involves consensus best-estimate diagnosis on the basis of all available data by two or more clinicians (28). Diagnostic data were extracted and rated independently on a random sample of 25 patients by a second experienced psychiatrist who trained at the Maudsley Hospital. There was a 100% concordance for DSM-III-R diagnoses for the 25 patients rated by two psychiatrists.

Cross-sectional symptomatic and social outcome were measured with several instruments. Cross-sectional measures of psychopathology were obtained by using the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (29), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (30), and the Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale (31). The total SAPS score represented the sum of scores on all 35 items (maximum score=170). The total SANS score represented the sum of scores on all 24 items (maximum score=120). The Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale rates severity of symptoms in the past month on an ordinal scale from 1 (most severe) to 90 (no symptoms). Cross-sectional social outcome/disability was measured with the Global Assessment of Functioning disability scale (31) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Disability Assessment Schedule (32). The Global Assessment of Functioning disability scale rates severity of disability in the past month on an ordinal scale from 1 (most severe) to 90 (no disability).

Course of illness and disability was assessed by using a slightly modified version of the Life Chart instrument from the WHO Multi-Centre Study on the Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia (31). The Life Chart assesses course of illness according to quality of remission, course type, and severity of symptoms, each with clear definitions. Two varieties of remission are distinguished: 1) complete remission, in which the subject is virtually symptom-free and shows his/her usual premorbid personality, and 2) incomplete remission, in which the subject is no longer psychotic but shows any combination of residual symptoms, nonpsychotic symptoms, or personality change. Course type characterizes the entire follow-up period in one of four ways: 1) continuous course, in which the patient was psychotic over most of the period and any remissions that occurred were brief (none longer than 6 months), 2) episodic course, in which discrete psychotic episodes (none longer than 6 months) occurred with clear periods of remission between episodes and at least one period of remission lasting 6 months or more, 3) mixed course, which had characteristics other than those of an episodic or continuous course (e.g., the longest psychotic episode lasted 12 months, and longest remission lasted 9 months), and 4) not psychotic, in which the patient was never actively psychotic during follow-up. Severity of symptoms during the majority of the follow-up period was characterized by four levels: 1) severe, in which the patient could not carry on a coherent conversation, could not work without close supervision, or required constant care; 2) moderate, in which the patient consistently showed signs of health despite marked psychotic symptoms, e.g., could speak with reasonable clarity on some occasions or could work or care for others to some extent; 3) mild, in which the patient’s behavior was generally normal and illness was not immediately obvious in conversation, although definite psychotic symptoms persisted; and 4) recovered, in which the patient experienced no psychotic symptoms or only residual symptoms.

The Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale range expressed the variability in levels of symptoms during the follow-up period and was defined as the difference between the highest and lowest Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale score for each subject. Variables measuring time were expressed as the proportion (percentage) of the individual follow-up period. The definition of employment included any time spent in full-time education or vocational training (or full-time child care). Independent adult living was defined as living either alone or with friends/partner or with parents and receiving no more support than would be received by the majority of individuals at a similar age.

Statistical Analysis

The stability of child and adolescent psychotic diagnoses was assessed by using the following indices: sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio, positive predictive value, and kappa coefficient of diagnostic agreement. Categorical data were analyzed with the chi-square test with Yates’s correction for continuity. Categorical r-by-two tables with ordered categories were analyzed with the chi-square test for linear trend. Fisher’s exact test was used when expected cell numbers were less than 5. For continuous variables, independent t tests were used when assumptions of normality and homogeneity were met. When appropriate, continuous variables were either transformed so assumptions were better met or analyzed with nonparametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test (corrected for ties). All reported tests of significance are two-tailed. Multiple linear regression was used to determine the extent of confounding by demographic variables (ethnicity, social class, area of residence, and gender) in the relationship between adolescent-onset diagnosis and outcome (Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale score).

Results

Stability of Adolescent-Onset Diagnoses

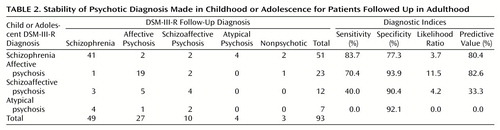

Table 2 shows the continuities between adolescent and adult follow-up DSM-III-R psychotic diagnoses. Among the 51 patients given a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia in adolescence, 41 received the same diagnosis as adults (positive predictive value=80%). Among the 23 patients given a diagnosis of affective psychosis in adolescence, 19 received the same diagnosis as adults (positive predictive value=83%). In contrast, schizoaffective psychosis had a positive predictive value of only 33% (only four of 12 patients received the same diagnosis as adults), and none of the seven patients diagnosed with atypical psychosis in adolescence received the same diagnosis at adult follow-up.

Although the sensitivity of the adolescent diagnoses for schizophrenia and affective psychosis were high (84% and 70%, respectively), sensitivity was low for schizoaffective psychosis (40%) and zero for atypical psychosis. The low number of false-positive diagnoses of adolescent affective psychosis contributed to a high specificity (94%) and the high likelihood ratio (11.5). In contrast, the likelihood ratio for schizophrenia was only 3.7. However, the higher rate of schizophrenia, relative to affective psychoses, in the sample resulted in very similar positive predictive values for adolescent diagnoses of schizophrenia and affective psychoses.

The overall diagnostic agreement (kappa) between adolescent-onset and adult DSM-III-R diagnoses were as follows: schizophrenia, kappa=0.61 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.45–0.77); affective psychosis, kappa=0.67 (95% CI=0.50–0.84); schizoaffective psychosis, kappa=0.28 (95% CI=–0.06–0.62); and atypical psychosis, kappa=–0.10 (95% CI=–0.40–0.20).

Predictive Validity of Adolescent-Onset Diagnosis

Prediction of clinical course and outcome

Table 3 shows the results of the comparison between the clinical course of adolescent-onset schizophrenia and other psychoses on measures adapted from the WHO Life Chart (31). The results indicate that an adolescent diagnosis of schizophrenia predicted a greater likelihood of a severe, unremitting illness course. Only 12% (N=6) of patients given a diagnosis of schizophrenia in adolescence were in complete remission for most of the follow-up, compared to 52% (N=22) of those with nonschizophrenic psychoses. Subjects with a diagnosis of adolescent-onset schizophrenia were psychotic for a greater proportion of the follow-up (N=46; median 84.0% of follow-up, interquartile range [IQR]=33.7–100) than were those with other psychoses (N=42; median 15.5%, IQR=8.3–39.0) (Mann-Whitney U, z=–4.49, p<0.0001).

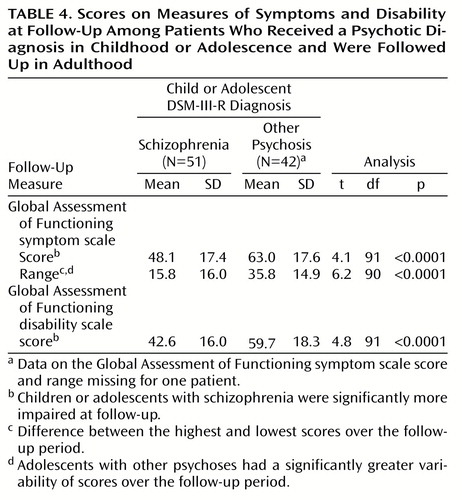

Table 4 shows that subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia were significantly more impaired at outcome than those with other psychoses. Compared to subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia, subjects with nonschizophrenic psychoses had greater symptom variability over the course of follow-up. At outcome, subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia had more negative symptoms (N=37, median total SANS score=30 of the maximum score of 120, IQR=13–49) than subjects with other psychoses (N=39, median total SANS score=4 of the 120 maximum score, IQR=0–25) (Mann-Whitney U, z=–4.14, p<0.0001) and more positive symptoms (median total SAPS score=14 of the maximum score of 170, IQR=3–21 for subjects with schizophrenia [N=48] versus median total SAPS score=0 of the 170 maximum score, IQR=0–12 for subjects with other psychoses [N=42]) (Mann-Whitney U, z=–3.12, p=0.002).

Independent adult living

Subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia spent less time living independently (N=50, median time independent <1 year, <1% of follow-up period) than subjects with nonschizophrenic psychoses (N=42, median time independent=5.9 years, 74% of follow-up period) (Mann-Whitney U, z=–4.5, p<0.0005). Twenty percent (N=10) of the subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia were living independently (nine of these 10 were still living with parents), compared to 50% (N=21) of subjects with other psychoses (10 of 21 were living with friends or partners). Thirty-two percent (N=16) of the subjects with schizophrenia had spent the majority of the follow-up period in long-stay residential or psychiatric hospital care, compared to only 17% (N=7) of subjects with other psychoses. There was a significant linear association between adolescent-onset schizophrenia and nonindependent adult living (χ2=10.8, df=5, p=0.001).

Education and employment

Sixty percent (N=30 of 50) of the subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia left school with no formal qualifications and undertook no further postschool training. Despite this overall low level of educational achievement, it is notable that 22% (N=11) achieved passes on the “GCSE” (General Certificate of Standard Education, the U.K. national scholastic examination for 16-year-olds) or the “A level” (U.K. national scholastic examination for 18-year-olds) after the onset of psychosis. Educational achievement was significantly better for those with nonschizophrenic psychoses, with only 33% (N=14) without any formal qualification or training, while 38% (N=16) achieved GCSE or higher qualifications. There was a significant linear association between the diagnosis of schizophrenia and low educational achievement (χ2=6.9, df=5, p<0.01).

Subjects with an adolescent diagnosis of schizophrenia spent significantly less time in employment over the follow-up period (N=50, median=0%, IQR=0%–18.0%) than subjects with nonschizophrenic psychoses (N=42, median=32.4%, IQR=5.0%–63.6%) (Mann-Whitney U, z=–3.73, p=0.0002).

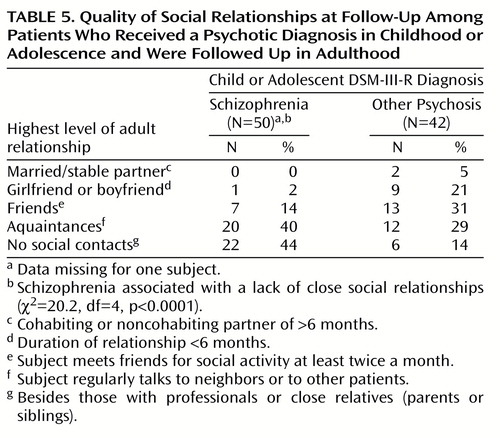

Social relationships in adult life

Table 5 indicates that adolescent-onset schizophrenia predicts impoverished social relationships in adult life. Almost half of subjects with adolescent-onset schizophrenia (N=22, 44%) had no social contacts other than with professionals or close relatives. Only 14% socialized with a friend or friends, only one subject had had a reciprocal love relationship, and none had married or had a stable partner. Subjects with an adolescent diagnosis of nonschizophrenic psychoses were much less socially impaired, with more than half (N=24, 57%) having either a regular friendship or love relationship.

The effect of demographic confounding on outcome

To estimate the magnitude of confounding in the association between diagnosis and symptomatic outcome, the Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale score was regressed on DSM-III-R adolescent-onset diagnostic category (schizophrenia versus nonschizophrenic psychosis) and the following variables were then added to the model: gender, social class, location (area of residence), and ethnicity. The unadjusted regression coefficient (Beta) for diagnosis was 14.9, and the fully adjusted regression coefficient (Beta) was 13.4. Overall, adjusting for demographic confounding had a minor effect (about 10%) on the association between diagnosis and symptomatic outcome.

Discussion

Methods

This study examined the predictive validity of a diagnosis of adolescent-onset DSM-III-R schizophrenia by measuring diagnostic stability and comparing course and outcome with those of other adolescent-onset psychoses. The study has significant strengths and represents the largest longitudinal follow-up of adolescent-onset schizophrenia we are aware of that was free from diagnostic bias and that included a nonschizophrenic comparison group. A high follow-up rate (84%) reduced the opportunity for attrition bias, and a mean duration of follow-up of more than 11 years ensured that the subjects had entered well into adult life. Furthermore, the complete follow-up group was representative of the local catchment area subgroup, which reduced the potential for significant referral bias. Hence, the diagnostic comparisons are likely to be valid and generalizable to other populations of adolescents with psychotic disorders. Observer bias could not have affected baseline assessments as they were conducted blind to outcome. Outcome assessments were also conducted blind to baseline diagnosis. A single interviewer at outcome obviated the issue of interrater reliability. The fact that a second experienced psychiatrist achieved 100% concordance for outcome diagnoses with the initial rater suggests that there was very little observer error. Demographic confounding (gender, ethnicity, social class, and area of residence) accounted for no more than 10% of the variability in outcome score (Global Assessment of Functioning symptom scale) due to diagnosis. It is possible that differences in the quality and approach to treatment may have affected outcome. However, this seems an unlikely explanation for the outcome differences, as equal proportions of patients with schizophrenia and with nonschizophrenic psychoses received their follow-up care at the Maudsley Hospital.

The main weakness of the design was the retrospective case ascertainment and the reliance on case note ratings of psychopathology. However, the OPCRIT rating method is well suited to rating case notes and has good demonstrated reliability and validity. Although the Maudsley case records were extremely detailed, the secondary rating of chart data collected by a large number of different examining psychiatrists is likely to have introduced considerable random error. Given this caveat, the observed continuity and predictive validity of diagnoses was impressive and may in fact underestimate true effects.

Stability of Diagnoses

Diagnostic stability was high for the adolescent DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia (positive predictive value=80%) and affective psychoses (positive predictive value=83%). In contrast, the positive predictive value was only 33% for schizoaffective psychosis and 0% for atypical psychosis. There was moderate diagnostic agreement between adolescent and adult follow-up diagnoses for schizophrenia and affective psychosis (kappa statistic), and agreement for schizoaffective and atypical psychoses was no better than chance. The results suggest that operationalized DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia and affective psychoses have substantial predictive validity when applied to a sample of adolescent-onset psychotic patients. However, the likelihood ratio for schizophrenia of 3.7 suggests lower predictive values would occur in samples with a lower prevalence of schizophrenia (i.e., among adolescents from community mental health settings rather than specialist centers).

The results of the study reported here challenge the widely held belief that diagnoses of adolescent schizophrenia and affective psychoses are unstable and are of doubtful validity (6, 15). The findings confirm the higher levels of diagnostic stability reported in some previous follow-up studies of adolescent-onset schizophrenia (19, 20, 33) and avoid the methodological limitations of these studies. Unlike the findings of Werry et al. (6), the results of the present study did not suggest that bipolar disorder was commonly preceded by an adolescent diagnosis of schizophrenia. There was also little evidence that schizophrenia commonly presents in the guise of affective or atypical psychoses in adolescence. Finally, the level of diagnostic stability for schizophrenia in this study was broadly similar to the level reported in studies of adult-onset schizophrenia that used DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria (11).

Predictive Validity of Adolescent-Onset Diagnoses

The psychiatric and social outcomes of adolescent-onset schizophrenia were significantly worse, across a broad range of clinical and social outcome measures, than the outcomes of nonschizophrenic psychoses. An adolescent diagnosis of schizophrenia predicted less independence, poorer educational achievement, less likelihood of employment or access to further education, and higher global disability scores. The most striking finding among the subjects with schizophrenia was the poverty of their social relationships in adult life. The chronic illness course and very poor outcome described here support findings from previous follow-up studies of child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia (6, 19, 20, 33) and suggest that schizophrenia with a very early onset predicts a more severe and unremitting illness course than the adult-onset form of the disorder (34, 35).

In summary, the results demonstrate a high degree of diagnostic stability and good predictive validity for DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia and affective psychoses in childhood and adolescence. In contrast, the diagnostic instability of schizoaffective and atypical psychoses highlights their uncertain nosological status. The high degree of longitudinal diagnostic stability for schizophrenia and affective psychoses provides compelling evidence of diagnostic validity because it suggests that outcome differences do not simply reflect good and poor prognosis extremes within a single disorder, but rather separate diagnostic groupings. The phenotypic continuity of schizophrenia from adolescence into adult life suggests that whereas child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia is clinically a more severe variant of the adult form of the disorder, it is likely to share a common etiology and neurobiology (7).

These findings should give clinicians greater confidence in making an early diagnosis of schizophrenia in children and adolescents. The very poor prognosis described here for child- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia suggests that early and aggressive treatment, special education, and support for families should begin as soon as possible after onset of psychosis. The similarity between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV diagnostic criteria suggests that the results of this study are likely to apply equally to DSM-IV diagnoses.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 7, 1999; revision received Apr. 24, 2000; accepted May 3, 2000. From the Division of Psychiatry, University of Nottingham. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hollis at the Section of Developmental Psychiatry, Division of Psychiatry, University of Nottingham, South Block, E Floor, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail).This study was supported by a Research Training Fellowship from the U.K. Medical Research Council. The author thanks Prof. Eric Taylor, Dr. Karmen Slaveska, Kate Garrett, and Pam Remon for their help with the study.

1.. Green W, Padron-Gayol M, Hardesty A, Bassiri M: Schizophrenia with childhood onset: a phenomenological study of 38 cases. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 35:968–976Crossref, Google Scholar

2.. McKenna K, Gordon C, Lenane M, Kaysen D, Fahey K, Rapoport J: Looking for childhood onset schizophrenia: the first 71 cases screened. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:616–635Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3.. Carlson GA, Strober M: Manic depressive illness in early adolescence: a study of clinical and diagnostic characteristics in six cases. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1978; 2:511–525Google Scholar

4.. Ballenger JC, Reus VI, Post RM: The “atypical” clinical picture of adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:602–606Link, Google Scholar

5.. Joyce PR: Age of onset in bipolar affective disorder and misdiagnosis as schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1984; 14:145–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6.. Werry JS, McClellan JM, Chard L: Childhood and adolescent schizophrenia, bipolar and schizoaffective disorders: a clinical and outcome study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:457–465Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7.. Jacobsen L, Rapoport J: Research update: childhood-onset schizophrenia: implications for clinical and neurobiological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1988; 39:101–113Crossref, Google Scholar

8.. Robins E, Guze SB: Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1970; 126:983–987Link, Google Scholar

9.. Fennig S, Kovaszany B, Rich C, Ram R, Pato C, Miller A, Rubenstein J, Carlson G, Schwartz JE, Phelan J, Lavelle J, Craig T, Bromet E: Six-month stability of psychiatric diagnoses in first-admission patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1200–1208Google Scholar

10.. Tsuang MT, Woolson RF, Winokur G, Crowe RR: Stability of psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia and affective disorders followed-up over a 30- to 40-year period. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:535–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11.. Mason P, Harrison G, Croudace T, Glazebrook C, Medley I: The predictive validity of a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:321–327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12.. Helzer JE, Brockington IF, Kendell RE: Predictive validity of DSM-III and Feighner definitions of schizophrenia: a comparison with research diagnosis criteria and CATEGO. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:791–797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13.. Helzer JE, Kendell RE, Brockington IF: Contribution of the six-month criterion to the predictive validity of the DSM-III definition of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1277–1280Google Scholar

14.. McGlashan TH: Testing four diagnostic systems for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:141–144Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15.. Zeitlin H: The Natural History of Psychiatric Disorder in Children: Institute of Psychiatry Maudsley Monograph 29. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1986Google Scholar

16.. McClellan J, McCurry C: Early onset psychotic disorders: diagnostic stability and clinical characteristics. Eur Child Adol Psychiatry 1999; 8(suppl 1):13–19Google Scholar

17.. Kydd RR, Werry JS: Schizophrenia in children under 16 years. J Autism Dev Disord 1982; 12:348–357Crossref, Google Scholar

18.. Gillberg CI, Hellgren L, Gillberg C: Psychotic disorders diagnosed in adolescence: outcome at age 30 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:1173–1185Google Scholar

19.. Cawthron P, James A, Dell J, Seagroatt V: Adolescent onset psychosis: a clinical and outcome study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:1321–1332Google Scholar

20.. Maziade M, Gingras N, Rodrigue C, Bouchard S, Cardinal A, Gauthier B, Tremblay G, Cote S, Fournier C, Boutin P, Hamel M, Roy M, Martinez M, Merette C: Long-term stability of diagnosis and symptom dimensions in a systematic sample of patients with onset of schizophrenia in childhood and early adolescence, I: nosology, sex and age of onset. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:361–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21.. Thorley G: The Bethlem Royal and Maudsley Hospitals’ clinical data register for children and adolescents. J Adolesc 1982; 5:179–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22.. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23.. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in psychotic illness: development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:764–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24.. Williams J, Farmer AE, Ackenheil M, Kaufmann CA, McGuffin P: A multicentre inter-rater reliability study using the OPCRIT computerized diagnostic system. Psychol Med 1996; 26:775–783Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25.. Craddock N, Asherson P, Owen MJ, Williams J, McGuffin P, Farmer A: Concurrent validity of the OPCRIT diagnostic system: comparison of OPCRIT diagnoses with consensus best-estimate lifetime diagnoses. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:58–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26.. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

27.. Harrington R, Fudge H, Rutter M, Fudge H, Hill J: Adult outcomes of child and adolescent depression, I: psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:465–473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28.. Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM: Best estimate lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:879–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29.. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

30.. Andreasen NC: Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

31.. World Health Organization: WHO Coordinated Multi-Centre Study on the Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia. Geneva, WHO, 1992Google Scholar

32.. Jablensky A, Schwartz R, Tomov T: WHO Collaborative Study of Impairments and Disabilities Associated With Schizophrenic Disorders: a preliminary communication: objective and methods. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1980; 285:152–163Crossref, Google Scholar

33.. Schmidt M, Blanz B, Dippe A, Koppe T, Lay B: Course of patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia during first episode occurring under age 18 years. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 245:93–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34.. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I, Smeeton N: The natural history of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl 1989; 15:1–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35.. Ram R, Bromet EJ, Eaton WW, Pato C, Schwartz JE: The natural course of schizophrenia: a review of first-admission studies. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:185–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar