Factor Analysis of the DSM-III-R Borderline Personality Disorder Criteria in Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The goal of this study was to examine the factor structure of the DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder in young adult psychiatric inpatients. METHOD: The authors assessed 141 acutely ill inpatients with the Personality Disorder Examination, a semistructured diagnostic interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders. They used correlational analyses to examine the associations among the different criteria for borderline personality disorder and performed an exploratory factor analysis. RESULTS: Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the borderline personality disorder criteria was 0.69. A principal components factor analysis with a varimax rotation accounted for 57.2% of the variance and revealed three homogeneous factors. These factors were disturbed relatedness (unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness); behavioral dysregulation (impulsivity and suicidal/self-mutilative behavior); and affective dysregulation (affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment). CONCLUSIONS: Exploratory factor analysis revealed three homogeneous components of borderline personality disorder that may represent personality, behavioral, and affective features central to the disorder. Recognition of these components may inform treatment plans.

Borderline personality disorder was first distinguished from the broader construct of borderline personality by Spitzer et al. (1), who clarified what soon after became DSM-III criteria. Recognizing that the term “borderline” had been used as an adjective to modify a large number of terms (including “condition,” “syndrome,” “personality,” “state,” “character,” “pattern,” “organization,” and “schizophrenia”), the Spitzer group distilled the range of uses into the two major ways that the term had been used most often. The first referred to “a constellation of relatively enduring personality features of instability and vulnerability with important treatment and outcome correlates” (1, p. 17). This conceptualization was consistent with the work of Gunderson and Singer (2), among others, and became the basis for DSM-III borderline personality disorder.

The second way the term was often used, according to the Spitzer group, was to “describe certain psychopathological characteristics, usually stable over time, and assumed to be genetically related to a spectrum of disorders including chronic schizophrenia” (1, p. 17). Use of the term in this manner is consistent with the use by Kety et al. in the Danish adoption studies (3, 4) and became the basis for DSM-III schizotypal personality disorder.

The DSM-III division of the borderline construct into borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder reduced the heterogeneity of the construct, but only to some extent. Patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder rarely meet the criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, thus reducing heterogeneity, but subjects diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder often meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder (5–8). Therefore, it is unclear whether the DSM-III divisions reduced heterogeneity or merely shifted the fuzzy boundaries from one construct to another. DSM-III-R increased the coverage of the diagnoses in DSM-III but also increased the diagnostic overlap (9).

One way to probe the fuzzy boundaries of diagnostic criteria is to use factor analysis to empirically identify meaningful components of the disorder. We were able to locate only three relevant factor analytic studies of borderline personality disorder criteria, one for DSM-III (6), one for DSM-III-R (10), and one for DSM-IV (11).

Rosenberger and Miller’s factor analysis of DSM-III criteria for borderline personality disorder (6), based on structured clinical interviews with 106 college undergraduates, revealed two factors. The first factor consisted primarily of interpersonal and identity criteria, and the second factor consisted of the regulation of behavior and affect. Subjects in the Rosenberger and Miller study were nonclinical, not necessarily in great distress, and limited in age range.

The factor analysis of DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder by Clarkin et al. (10), based on a study group of 75 women hospitalized on an inpatient borderline treatment unit, identified three factors. The first factor included the borderline patient’s problematic interpersonal relationships and identity; the second was an affective dimension including suicidality; and the third was impulsivity. This analysis was limited by including only patients who met a sufficient number of criteria for the diagnosis. To discriminate which criteria are essentially borderline, it is important to include patients exhibiting a full range of borderline personality disorder criteria.

More recently, Fossati et al. (11) tested whether borderline personality disorder is a unitary construct using confirmatory factor analysis on DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a study group that included both inpatients and outpatients. In contrast to the two earlier factor analytic studies of borderline personality disorder criteria (6, 10), the analysis by Fossati et al., who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, was generally consistent with the concept that borderline personality disorder reflects a unidimensional construct. Although Fossati et al. observed some variability from the rank ordering of borderline personality disorder criteria as listed by DSM-IV, their results were reasonably parsimonious with the borderline personality disorder category. Nonetheless, they correctly noted that “diagnostic homogeneity does not imply the absence of natural subgroups” of patients with borderline personality disorder (11, p. 77). Indeed, there were hints of a possible dimensional gradient involving impulsivity and anger dyscontrol apart from the borderline personality disorder categorical construct.

The Fossati et al. findings (11), coupled with the previous factor analytic studies suggesting heterogeneity (6, 10), highlight the need for continued work in this area. In the current study, we probed DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder for homogeneous elements. Using a study group of psychiatric inpatients, we examined the internal consistency of borderline personality disorder and performed an exploratory factor analysis to identify a meaningful latent structure in the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were drawn from adult inpatients hospitalized between 1986 and 1990 at the Yale Psychiatric Institute, a private, not-for-profit, acute-care facility. There were 142 such adults (117 were consecutively admitted), representing nearly all of the adult inpatient admissions during this time period (12). For this report, we used all adult inpatients for whom there were complete data on borderline personality disorder (N=141); no other selection criteria were applied. Of the 141 subjects, 75 (53%) were men. They ranged in age from 18 to 39 years (mean=22.4, SD=4.7). Most of the subjects were Caucasian (N=126, 89%), and most fell in the middle-class range (classes II–IV) on the Hollingshead-Redlich scale (13). After complete explanation of the study procedures, and before starting the interviews, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Procedure

All subjects received a systematic diagnostic evaluation, including the Personality Disorder Examination (14), a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses for the presence of all 11 recognized DSM-III-R personality disorders. Items and diagnoses on the Personality Disorder Examination are scored as 0 (absent), 1 (probable), and 2 (definite). In adult subjects, traits must have been pervasive and persistent for a minimum of 5 years, and criteria are generally stringent; therefore, a score of 1 (probable) represents a clinical level of pathology (14).

Interviews were performed by a trained and monitored research evaluation team who functioned independently of the clinical team. Interrater reliability of Personality Disorder Examination diagnoses was assessed by independent, simultaneous ratings by pairs of raters on 26 patients from the overall study group. The kappa coefficient (15) for ratings of borderline personality disorder was 0.77; kappas ranged from 0.65 for paranoid personality disorder to 1.0 for histrionic, avoidant, and passive-aggressive personality disorders (mean kappa=0.84). Final research diagnoses were assigned at an evaluation research conference approximately 4 weeks after admission. Research diagnoses were established by the best-estimate method on the basis of the semistructured interviews and any additional relevant data from the clinical record, following the longitudinal, expert, all-data (LEAD) standard (16, 17). The Personality Disorder Examination and best-estimate research diagnoses concurred in more than 85% of the cases.

Results

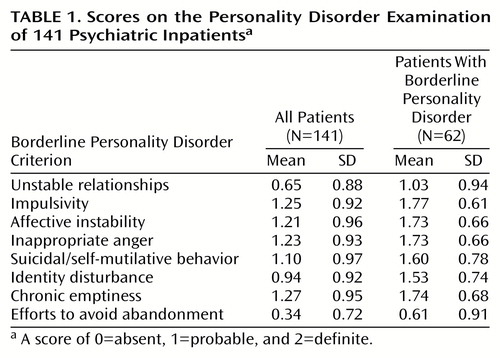

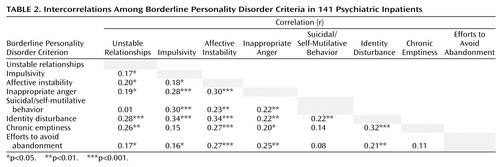

Sixty-two (44%) of the 141 participants met criteria for borderline personality disorder. Table 1 shows the mean scores on the Personality Disorder Examination of all patients as well as those who met criteria for borderline personality disorder. Noteworthy is the low rate of endorsement for the criterion of efforts to avoid abandonment. Cronbach’s alpha (18) for the borderline personality disorder criteria set was 0.69, suggesting adequate internal consistency. Table 2 shows the intercorrelations among the borderline personality disorder criteria. Overall, the internal consistency of the criteria was further supported by the strength of the relationships among the items. Of note, affective instability and identity disturbance were significantly correlated with the entire set of borderline personality disorder criteria.

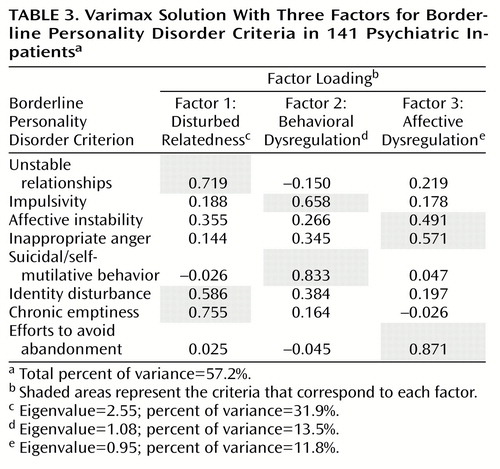

A principal components factor analysis (19) was conducted on all of the borderline personality disorder criteria. The results of this analysis indicated that the most appropriate solution involved three factors. A varimax (orthogonal) rotation specifying a three-factor solution accounted for 57.2% of the variance. We repeated the analyses using principal-axis factoring, and the two solutions were nearly identical (Tucker’s coefficient of congruence [20] ranged from 0.97 to 0.99 for the three factors).

Table 3 summarizes the results from the varimax rotation for the three-factor solution. The first factor, disturbed relatedness, consisted of the unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness criteria. The second factor, behavioral dysregulation, consisted of the impulsivity and suicidal/self-mutilative behavior criteria. The third factor, affective dysregulation, consisted of the affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment criteria.

The relative magnitude of the contribution made by each factor to explaining the presence of borderline personality disorder was also examined. Effect sizes (21) were computed by using the F value for factor scores pertaining to each factor to independently predict group membership (absent, probable, or definite borderline personality disorder diagnosis). All of the effect sizes were large in magnitude, ranging from 0.74 to 0.88.

Discussion

Using a reliably administered diagnostic instrument, we conducted a factor study of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in a group of young adult psychiatric inpatients. Overall, borderline personality disorder items appeared to demonstrate adequate internal consistency, as suggested by the criteria intercorrelations and by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.69. Two criteria, affective instability and identity disturbance, were significantly correlated with the entire borderline personality disorder criteria set, suggesting that these two items are core features of the disorder in this study group. In an exploratory factor analysis of the items, a three-factor solution appeared most appropriate, both empirically (i.e., on the basis of the interpretation of the principal components analysis) and theoretically (i.e., on the basis of the conceptual quality of the factors). The three-factor model accounted for 57.2% of the variance, and effect sizes based on the variance in the borderline personality disorder diagnosis explained by the factors were all large in magnitude, suggesting that each represents an important component of the disorder.

The three identified factors hold conceptual appeal. The first factor, disturbed relatedness, consists of the criteria of unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness. This factor reflects a deficit in the sense of self and inability to relate to others, something that might have been historically termed “anaclitic.” In many ways, this factor can be viewed as a core personality aspect of borderline personality disorder in that the disturbed and incomplete sense of self is an underpinning of much of the symptomatic interpersonal behavior seen in individuals with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. In addition, identity disturbance was correlated with the remaining borderline personality disorder criteria (Table 2).

The second factor, behavioral dysregulation, consists of the impulsivity and suicidality/self-mutilative behavior criteria. This factor captures the most treatment-relevant symptomatic behavior of an individual with borderline personality disorder. It is different from the other factors and criteria in the sense that these are behaviors as opposed to symptoms, character traits, or temperaments. For our group of acutely disturbed psychiatric inpatients, in all likelihood these are the criteria that called attention to the disorder and led to hospitalization.

The third factor, affective dysregulation, consists of the criteria of affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment. This factor might reflect the hypothesized physiological temperament of borderline personality disorder (22, 23) or, more specifically, may express how effectively individuals with core borderline personality disorder moderate their response to stress. At first blush, the finding that efforts to avoid abandonment loads heavily on this factor might appear to be an anomaly; however, one can imagine that abandonment concerns plus poor affective dysregulation may translate directly into typical “borderline” behavioral manifestations (for example, refusing to leave a therapist’s office—an event with typically highly charged affect). On the other hand, this finding could be a statistical artifact of the low base rate of endorsement of this item (Table 1) and therefore specific to our study group.

Rosenberger and Miller’s factor analysis of DSM-III borderline personality disorder with college undergraduates (6) produced two factors. One factor consisted of the identity disturbance, efforts to avoid abandonment, emptiness, and unstable relationships criteria. The second factor consisted of the affective instability, impulsivity, self-damaging acts, and inappropriate anger criteria. In contrast, the results from the present study appear to parse out the impulsive behavior criteria from the unstable affect criteria. The criteria that make up our behavioral dysregulation factor are qualitatively different from other borderline personality disorder criteria in that they reflect symptomatic behaviors as opposed to symptoms, temperaments, or traits. In fact, the behavioral dysregulation factor may involve the most pernicious (and potentially lethal) criteria for the clinician to consider when treating a patient with borderline personality disorder (24). The independence of this factor is also consistent with results from the longitudinal stability study of borderline personality disorder criteria conducted by Links et al. (25), who demonstrated the stability of the borderline personality disorder impulsiveness criterion, suggesting that it is a key feature of borderline personality disorder. Links et al. also pointed out that targeting the impulsive behaviors may be the best way to have a positive impact on the prognosis of the disorder.

The factor analysis of DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in female inpatients by Clarkin et al. (10) identified three factors. The first factor consisted of emptiness/boredom, identity disturbance, efforts to avoid abandonment, and unstable relationships. Unstable relationships also loaded to a smaller degree on the second factor, along with suicidality, anger, and labile affect. Their third factor consisted of the impulsivity criterion alone, although labile affect loaded negatively on this factor. In contrast, our results appear to be divided more into factors broadly reflecting personality, behavior, and affect. Perhaps this derives from our more heterogeneous study group, which included both men and women and patients with and without borderline personality disorder, thus providing a broader range of phenomenological variation.

The study by Fossati et al. (11) tested the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder as a diagnostic category. Their main results were supportive of ours, although exploratory latent class analyses suggested a dimensional subcategory of inappropriate anger and impulsivity. This dimension appears related to our second factor of behavioral dysregulation insofar as they share elements of impulsivity and aggression. In our patients the aggression appears to be expressed in self-directed form (suicidal/self-mutilative), and in the study group of Fossati et al. it appears more generic (inappropriate anger).

Our study has certain strengths and limitations. Our borderline personality disorder symptom data were obtained by means of the reliable use of the Personality Disorder Examination (14) by highly trained and monitored clinicians. Our results were based on DSM-III-R, however, and thus have limited applicability to DSM-IV; it will be important to determine if the same patterning of components holds for the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder diagnosis in future studies. Although the fact that our patients were acutely ill may influence the endorsement of criteria and the assignment of diagnosis of personality disorders (26), the conservative duration criterion specified by the Personality Disorder Examination (14) may have minimized such state-trait artifacts (27). In addition, our assessment procedures were implemented a few weeks after admission, thus eliminating acute decompensation and the potential effects of substance withdrawal. Because our study group was composed of acutely ill psychiatric patients requiring inpatient level treatment, our findings may not be generalizable to outpatients or community samples.

To summarize, our exploratory factor analysis suggests that there may be homogeneous domains of borderline personality disorder criteria and that some of these domains reflect symptoms, others reflect traits, and still others reflect symptomatic behaviors (28). These findings may help to outline central components of the disorder and can also inform treatment plans by identifying subsets of criteria that may be more or less responsive to different treatment interventions. For instance, treatment plans may specify medication to target the affective dysregulation factor, cognitive behavior treatment could be used to target the behavioral dysregulation factor, and longer-term psychotherapy may be necessary for the disturbed relatedness factor.

Our factor model should be tested in another group of subjects by using confirmatory factor analysis with particular attention paid to the class of criteria (e.g., behavioral, temperament, personality). Additional tests of factor analytic models are also needed in more broadly based groups of subjects. Finally, temporal stability of the factors should be examined in longitudinal studies. It may be that some factors are stable (such as our disturbed relatedness and affective dysregulation factors) but that others appear only when an individual is severely stressed (such as our behavioral dysregulation factor).

|

|

|

Received July 28, 1999; revisions received Feb. 16 and May 5, 2000; accepted May 22, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Sanislow, Yale Psychiatric Research, P. O. Box 208038, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520-8038; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-01654 (Dr. McGlashan).The authors thank William Edell, Ph.D., for support in the development of the Yale Psychiatric Institute Evaluation Unit and Leslie C. Morey, Ph.D., for statistical advice.

1.. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M: Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: the development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:17–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2.. Gunderson JG, Singer MT: Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:1–10Link, Google Scholar

3.. Kety SS, Rosenthal D, Wender PH, Schulsinger F: Mental illness in the biological and adoptive families of adopted schizophrenics. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 128:302–306Link, Google Scholar

4.. Rosenthal D, Wender PH, Kety SS, Welner J, Schulsinger F: The adopted-away offspring of schizophrenics. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 128:307–311Link, Google Scholar

5.. Nurnberg HG, Raskin M, Levine PE, Pollack S, Siegel O, Prince R: The comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and other DSM-III-R axis II personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1371–1377Google Scholar

6.. Rosenberger PH, Miller GA: Comparing borderline definitions: DSM-III borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1983; 98:161–169Crossref, Google Scholar

7.. Stuart S, Pfohl B, Battaglia M, Bellodi L, Grove W, Cadoret R: The cooccurrence of DSM-III-R personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1998; 12:302–315Crossref, Google Scholar

8.. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V: Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1998; 39:296–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9.. Morey LC: Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R: convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:573–577Link, Google Scholar

10.. Clarkin JF, Hull JW, Hurt SW: Factor structure of borderline personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:137–143Crossref, Google Scholar

11.. Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Donati D, Caterina N, Novella L: Latent structure analysis of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:72–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12.. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Quinlan DM, Walker ML, Greenfeld D, Edell WS: Frequency of personality disorders in two age cohorts of psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:140–142Link, Google Scholar

13.. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1958Google Scholar

14.. Loranger AW, Susman VL, Oldham JM, Russakoff M: The Personality Disorder Examination (PDE) Manual. Yonkers, NY, DV Communications, 1988Google Scholar

15.. Cohen J: A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychol Measurement 1960; 20:37–46Crossref, Google Scholar

16.. Pilkonis PA, Heape CL, Ruddy J, Serrao P: Validity in the diagnosis of personality disorders: the use of the LEAD standard. Psychol Assessment 1991; 3:46–54Crossref, Google Scholar

17.. Spitzer RL: Psychiatric diagnoses: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry 1983; 24:399–411Google Scholar

18.. Cronbach LJ: Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951; 16:297–334Crossref, Google Scholar

19.. Norusis MJ: SPSS for Windows: Base System User’s Guide and Advanced Statistics, Release 6.1. Chicago, SPSS 1994Google Scholar

20.. Harman HH: Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1976Google Scholar

21.. Cohen J: Statistical Power for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, Academic Press, 1977Google Scholar

22.. Stone MH: Toward a psychobiological theory of borderline conditions. Dissociation 1988; 1:1–15Google Scholar

23.. Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR: A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:975–990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24.. Linehan M: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

25.. Links PS, Heslegrave R, van Reekum R: Impulsivity: core aspect of borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1999; 13:1–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26.. Zimmerman M: Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:225–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27.. Loranger AW, Lenzenweger MF, Gartner AF, Susman VL, Herzig J, Zammit GK, Gartner JD: Trait-state artifacts and the diagnosis of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:720–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28.. Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH: Treatment outcome of personality disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1998; 43:237–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar