Anxiety in Major Depression: Relationship to Suicide Attempts

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was an examination of the relationship of lifetime panic disorder and anxiety symptoms at index hospitalization to a history of a suicide attempt in patients with a major depressive episode. METHOD: A total of 272 inpatients with at least one major depressive episode, with or without a history of a suicide attempt, were entered into the study. They were given structured diagnostic interviews for axis I and axis II disorders. Suicide attempt history, current psychopathology, and traits of aggression and impulsivity were also assessed. RESULTS: The rates of panic disorder did not differ in the suicide attempters and nonattempters. Agitation, psychic anxiety, and hypochondriasis were more severe in the nonattempter group. A multivariate analysis confirmed that this effect was independent of aggression and impulsivity. CONCLUSIONS: Comorbid panic disorder in patients with major depression does not seem to increase the risk for lifetime suicide attempt. The presence of greater anxiety in the nonattempters warrants further investigation.

Panic disorder and anxiety symptoms are hypothesized risk factors for suicidal behavior. However, studies of the relationship of suicidal acts to anxiety in either the presence or absence of major depression have yielded conflicting results.

Some studies have indicated that patients with panic disorder have the same rates of suicide as patients with major depression (1, 2). Others have shown a lower incidence of suicide in “pure” panic disorder (3–5). One reason for the discrepancy among results in the literature may lie in the failure of studies with smaller, convenience samples to take into account other factors that predispose patients to suicidal behavior. Such factors include comorbid mood disorders, traits of aggressivity and impulsivity, a family history of suicidal acts, and comorbid substance abuse or alcoholism. For example, in a study of patients with panic disorder (6), patients with a history of depression had a higher rate of attempted suicide than the patients without depression (70.6% versus 29.4%). However, this study did not evaluate other putative risk factors, such as axis II disorders and lifetime traits such as aggression and impulsivity.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether panic disorder or anxiety symptoms are associated with a history of suicidal behavior in depressed inpatients, by using both a categorical diagnosis and dimensional measures of anxiety. To this end, structured clinical interviews were used to determine axis I and II diagnoses. Moreover, lifetime aggression and impulsivity, known correlates of suicidal behavior (7), were also measured.

Method

Subjects

The study participants were 272 patients aged 17–72 years who were admitted to a university psychiatric hospital for the treatment of mood disorders. All patients gave written informed consent as approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Each patient had a history of at least one major depressive episode and met the DSM-III-R criteria for major depression or bipolar disorder. The patients had no active medical or neurological problems or current alcohol or substance abuse.

Measures

DSM-III-R axis I and II disorders were diagnosed by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) for axis I (8) and axis II (9) disorders. Psychiatric symptoms were rated with the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (10), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (11), and the Beck Depression Inventory (12). The items for agitation, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, and hypochondriasis from the Hamilton depression scale and the items for anxiety, somatic concern, and tension from the BPRS were used to measure the presence of anxiety symptoms. Lifetime aggression and impulsivity were rated by using the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Inventory (13) and the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (14), respectively.

A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act carried out with at least some intent to end one’s life. The Scale for Suicidal Ideation (15) was used to measure suicidal ideation during the 2 weeks before hospitalization. The subject’s intent to die at the time of the attempt was assessed by using the Suicide Intent Scale (16). The lethality or medical damage inflicted by suicide attempts was measured with the Medical Damage Rating Scale (16).

The raters each had a master’s or doctorate degree and had met our previously reported criteria for reliability (7).

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square analyses and Student’s t tests were used to contrast attempters and nonattempters. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the rates of panic disorder and borderline personality disorder diagnoses in the two groups when the expected counts in some cells were not sufficiently high. A multivariate analysis of variance for Hamilton depression scale anxiety symptoms and BPRS anxiety symptoms by attempter status was performed. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Of the total subjects, 143 (52.6%) had attempted suicide and 129 (47.4%) had not. The two subgroups did not differ on demographic characteristics (data available on request). The mean age of the entire study group was 35.2 years (SD=11.7); 42.6% were male (N=116), and 77.9% were Caucasian (N=212).

One-third of the subjects (34.2%, N=93)—more than one-half of the attempter group—had made multiple suicide attempts. At least one comorbid diagnosis was identified in 42.6% of the study group (N=116). The suicide attempters and nonattempters differed significantly in the numbers with axis I and axis II comorbid disorders; both were more common among the attempters (Table 1).

Panic disorder was present in 26 subjects (9.6%; four men and 22 women). The attempters did not differ significantly from the nonattempters in lifetime rate of panic disorder (Table 1).

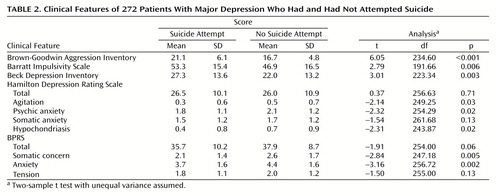

The attempters scored higher on subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory) than the nonattempters, but they did not differ in severity of objective depression (Hamilton depression scale total) or general psychopathology (BPRS total) (Table 2).

The mean score for anxiety items on the Hamilton depression scale was higher in the nonattempter group, and there were significant differences for agitation, psychic anxiety, and hypochondriasis (Table 2). The BPRS mean score for anxiety was also higher in the nonattempter group, and there were significant differences for the somatic concern and anxiety items (Table 2). A Hotelling T2 test multivariate comparison of the attempters and nonattempters indicated significant differences between groups for the Hamilton scale anxiety symptoms (F=2.78, df=4, 260, p=0.03), the BPRS anxiety symptoms (F=5.03, df=3, 255, p=0.002), and the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory scores (F=18.70, df=2, 202, p=0.001). Thus, the mean scores for anxiety and the combination of aggressivity and subjective depression were significantly different in the attempters and nonattempters (also see Table 2).

After adjustment for panic disorder and anxiety measures, a logistic regression of suicide attempter status on aggressivity showed that aggressivity was still highly predictive of attempter status (likelihood ratio test: χ2=28.71, df=1, p<0.001). Using a likelihood ratio test based on a logistic regression, we found that panic disorder and anxiety measures together, with adjustment for aggression, were significant predictors of attempter status (likelihood ratio test: χ2=30.70, df=16, p=0.001). But it was higher anxiety in the nonattempters that explained the finding.

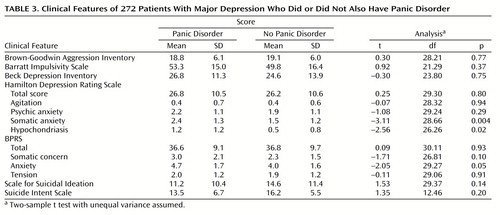

The patients with panic disorder had higher mean scores on the somatic anxiety and hypochondriasis items of the Hamilton depression scale than the patients without panic disorder (Table 3). The patients with panic disorder did not significantly differ from those without panic disorder on the measures of aggression and impulsivity or on the total scores on the Hamilton depression scale, BPRS, or Beck Depression Inventory (Table 3). There was also no difference in lethality scores between the patients with and without panic disorder. No significant correlation between anxiety measures and lethality was found.

Discussion

The major results of this study are that a lifetime history of a suicide attempt in patients with a major depressive episode is unrelated to a history of panic disorder and is associated with less severe symptoms of agitation and anxiety.

To our knowledge, only one previous study (17) compared the incidence of suicide attempts among depressed patients with and without panic disorder. In that study there was a higher frequency of suicide attempts in patients with infrequent panic attacks than in those with panic disorder or with depression only. In 47% of the subjects the panic attacks began after the suicide attempt or were not present at the moment of the attempt. Thus, that study did not suggest that panic attacks directly increased the risk of suicide attempt. Female gender and a history of psychosis, but not panic attack history, significantly related to a history of suicidal behavior.

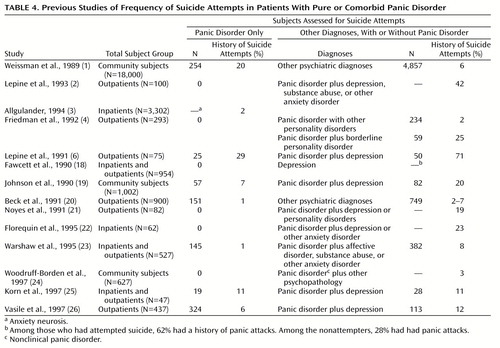

Other investigators (Table 4) studied patients with panic disorder and patients with comorbid panic disorder, reporting an incidence of suicide attempts from 1% to 29% in the patients with panic disorder alone (mean=9.6, median=6.5) and from 2% to 71% in the patients with comorbid panic disorder (mean=19.1, median=12.0). The variance of the values and the fact that the group with comorbid conditions had a median rate double that of the group with panic disorder alone suggest that comorbidity is an important factor in suicidal acts. The rate of suicide attempts in panic disorder alone may still be higher than in the general population.

Investigators in three studies (2, 21, 24) calculated the incidence of suicide attempts in a population of comorbid panic disorder patients, reporting rates of 42%, 19%, and 3%. The percentage of suicide attempters in our group of patients with comorbid panic disorder was 53.3%. Such different rates suggest that a major reason for variance in suicidal behavior is related to factors other than comorbid panic disorder. This conclusion is consistent with the report by Beck et al. (20) of a higher rate of suicide attempts in patients with a primary mood disorder and secondary panic disorder than in subjects with panic disorder and secondary mood disorder.

Borderline personality disorder and the traits of aggression and impulsivity have been found to be associated with suicide. In our study group, we found a significantly higher rate of borderline personality disorder in attempters than in nonattempters (27.2% versus 6.7%, respectively). Similarly, Friedman et al. (4) reported that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in a group of patients with borderline personality disorder and panic disorder was 25%, compared with 2% in patients with panic disorder only. Noyes et al. (21), in a 7-year follow-up study of patients with panic disorder, found completed suicide only in panic disorder patients with comorbid severe depression or personality disorder. This suggests that suicide is not related to panic disorder alone, a possibility that is consistent with our results.

Levels of aggression and impulsivity correlate with past suicidal behavior (7), but few studies have examined the relationship of aggression, impulsivity, and anxiety symptoms. We previously reported (7) that suicide attempters have more lifetime aggression and impulsivity than nonattempters and that aggression is greater in patients with cluster B personality disorder diagnoses. In this study, the relationship of aggression and impulsivity to history of suicidal acts was independent of the presence of anxiety symptoms or panic disorder (Table 2). Thus, aggression and impulsivity should be assessed in studying suicidal behavior in order to avoid confounding results.

We found that nonattempters had significantly higher scores on the Hamilton and BPRS anxiety items than attempters. A study of anxiety measures in suicidal adolescents (27) showed higher state and trait anxiety levels in attempters than in nonattempters. The disagreement between these results and ours could be partially explained by differences between subject groups.

In a group of adults, Fawcett et al. (18) found a higher rate of psychic anxiety in patients with acute suicide risk (suicide in less than 1 year from the time of interview); however, the suicidal patients had higher alcohol abuse ratings than the comparison groups. The link between suicidal behavior and anxiety symptoms observed by some authors could be explained by the presence of substance abuse in patients with high anxiety levels.

In our study group, greater anxiety was present in the nonattempters. Anxiety may be protective if it is associated with fear of death or illnesses. These results need confirmation because the implications for the use of antianxiety medications in patients with major depression and anxiety symptoms are profound. Such agents may increase the risk of suicide attempts and suicide. In a Swedish study (28) it was found that many depressed persons who committed suicide had received anxiolytics instead of antidepressants shortly before death. Perhaps their physicians were responding to the anxiety symptoms of depression, thereby not only failing to treat the depression but possibly facilitating suicide by reducing anxiety.

Our study has the following limitations. Because our study group included only inpatients, the severity of psychopathology was not representative of the general population. Furthermore, although we did not find a relationship between a history of panic disorder and suicide attempts, we did not have information about the relationship between onset of panic disorder and suicide attempts. In addition, we based our analyses on seven anxiety items from the Hamilton depression scale and BPRS, rather than from a scale specifically designed to measure anxiety.

In conclusion, the presence of panic disorder in the context of a major depressive episode does not seem to be associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior in this inpatient population. Furthermore, higher levels of anxiety, agitation, and hypochondriasis appear to represent putative protective factors for suicidal behavior among such patients. We could infer that anxiety might restrain patients with suicidal ideation from acting on their suicidal impulses. However, sufficiently severe suicidal ideation and hopelessness, combined with impulsivity, could override anxiety and lead the patient to attempt suicide.

|

|

|

|

Received July 19, 1999; revisions received Nov. 16, 1999, and Feb. 18, 2000; accepted May 12, 2000. From the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mann, Department of Neuroscience, Box 42, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-46745 and MH-48514.The authors thank Maura Boldrini, M.D., for assistance in the revision of this article.

1.. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Markowitz JS, Ouellette R: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1209–1214Google Scholar

2.. Lepine JP, Chignon JM, Teherani M: Suicide attempts in patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:144–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3.. Allgulander C: Suicide and mortality patterns in anxiety neurosis and depressive neurosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:708–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4.. Friedman S, Jones JC, Chernen L, Barlow DH: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among patients with panic disorder: a survey of two outpatient clinics. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:680–685Link, Google Scholar

5.. Noyes R Jr: Suicide and panic disorder: a review. J Affect Disord 1991; 22:1–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6.. Lepine J-P, Chignon J-M, Teherani M: Suicidal behavior and onset of panic disorder (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:668–669Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7.. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

8.. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

9.. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

10.. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11.. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

12.. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13.. Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF: Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979; 1:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14.. Barratt ES: Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychol Rep 1965; 16:547–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15.. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16.. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors, I: quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

17.. King MK, Schmaling KB, Cowley DS, Dunner DL: Suicide attempt history in depressed patients with and without a history of panic attacks. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:25–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18.. Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1189–1194Google Scholar

19.. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Panic disorder, comorbidity, and suicide attempts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:805–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20.. Beck AT, Steer RA, Sanderson WC, Skeie TM: Panic disorder and suicidal ideation and behavior: discrepant findings in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1195–1199Google Scholar

21.. Noyes R Jr, Christiansen J, Clancy J, Garvey MJ, Suelzer M, Anderson DJ: Predictors of serious suicide attempts among patients with panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1991; 32:261–267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22.. Florequin C, Hardy P, Messiah A, Ellrodt A, Féline A: Tentatives de suicide et trouble panique: étude de 62 suicidants hospitalisés. L’Encéphale 1995; 21:87–92Medline, Google Scholar

23.. Warshaw MG, Massion AO, Peterson LG, Pratt LA, Keller MB: Suicidal behavior in patients with panic disorder: retrospective and prospective data. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:235–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24.. Woodruff-Borden J, Stanley MA, Lister SC, Tabacchi MR: Nonclinical panic and suicidality: prevalence and psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 1997; 35:109–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25.. Korn ML, Plutchik R, Van Praag HM: Panic-associated suicidal and aggressive ideation and behavior. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31:481–487Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26.. Vasile RG, Goldenberg I, Reich J, Goisman RM, Lavori PW, Keller MB: Panic disorder versus panic disorder with major depression: defining and understanding differences in psychiatric morbidity. Depress Anxiety 1997; 5:12–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27.. Ohring R, Apter A, Ratzoni G, Weizman R, Tyano S, Plutchik R: State and trait anxiety in adolescent suicide attempts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:154–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28.. Isacsson G, Boëthius G, Bergman U: Low level of antidepressant prescription for people who later commit suicide:15 years of experience from a population-based drug database in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:444–448Google Scholar