A Single Session With an Earthquake Simulator for Traumatic Stress in Earthquake Survivors

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the effectiveness of a single session of earthquake simulator-assisted exposure treatment of traumatic stress in earthquake survivors. METHOD: Ten earthquake survivors in Turkey were given one session of exposure to simulated earthquake tremors. Assessments were at pre- and postsession and at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks posttreatment. RESULTS: All measures showed significant improvement at all assessments. Eight patients were markedly and two slightly improved at follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: A single exposure session with an earthquake simulator appears to be effective in treating postearthquake traumatic stress. Controlled studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Although cognitive behavior therapy is known to be effective in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), its usefulness has not been examined in earthquake survivors. Cognitive behavior therapy is regarded as a brief form of psychotherapy, but it may not be brief enough in postdisaster cognitive behavior therapy settings, where hundreds of thousands of earthquake survivors may need urgent care. To our knowledge, no study has yet investigated whether it can be shortened further without compromising its effectiveness. The present report represents an effort to maximize the effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy in earthquake survivors and shorten it to one session by using an earthquake simulator. In an uncontrolled clinical trial, we examined whether a single session of earthquake simulator-assisted exposure caused significant improvement in earthquake-related PTSD symptoms.

Method

The present report originated from a project set up in September 1999 to develop brief and effective treatments for earthquake survivors in Turkey. The study involved 10 survivors consecutively referred for treatment between January and July 2001. Inclusion criteria were age 16 to 50 years, earthquake-related PTSD symptoms, and willingness to receive exposure treatment in an earthquake simulator. Survivors with predominating depression and a history of cardiovascular problems, psychotic illness, or substance dependence were excluded. The patients were given a detailed description of the treatment rationale and procedures. Only verbal consent was obtained because the treatment was given as part of a routine service delivery program and no control condition was used.

The treatment was conducted by using an earthquake simulator that consists of a small furnished house based on a shake table that can simulate earthquake tremors on nine intensity levels. The treatment consisted of a single 1-hour session. The patients controlled the tremors (using a mobile control switch in the earthquake simulator), stopping or starting it anytime they wanted and increasing the intensity whenever they felt ready for it. This was designed to help them gain a sense of control over the tremors and associated distress. Once the patients felt comfortable, they were encouraged to move one level up in intensity, but this decision was always left to them. The highest level ever attempted was level 5, which simulated tremors as strong as those of the 1999 earthquake (7.4 on the Richter scale). The session was terminated when the patients reported a substantial reduction in, and control over, their distress. No further self-exposure instructions were given after the session.

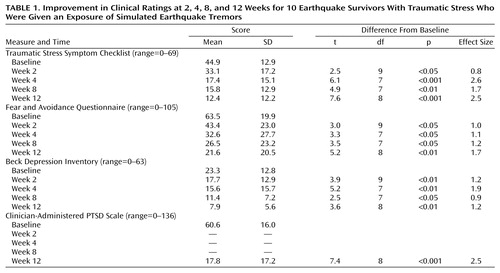

Assessments were conducted at pretreatment and 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks posttreatment. The measures included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (1), the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (2), the Traumatic Stress Symptom Checklist (3), the Beck Depression Inventory (4), and the Fear and Avoidance Questionnaire (5), which measures the intensity of fear and avoidance associated with 35 activities or trauma reminders (0=no fear/avoidance, 3=extreme fear/avoidance). Overall clinical improvement was measured by the Patients’ Global Impression of Improvement (6).

After the session, the patients rated the similarity between the earthquake simulator and real earthquake experience on a scale of 0 (none at all) to 4 (identical), presession to postsession change in distress associated with trauma-related memories rated on a 1–7 scale, and their satisfaction with the treatment (0=none at all, 3=very much). Paired t tests (two-tailed) were used to examine pre- to posttreatment change in the clinical ratings.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 36 years (SD=8); all were women and married. Five patients’ houses had collapsed, and three patients had been trapped under the rubble. The mean time since the earthquake was 20 months (SD=2). Eight patients met the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale diagnosis for PTSD, and four met the SCID diagnosis for major depression.

Eight patients rated the earthquake simulator experience as “identical” or “very similar” to a real earthquake. All of the patients reported “much/very much” reduction in associated distress and were “much/very much” satisfied with the treatment at postsession and at all follow-up assessments.

The mean scores on clinical ratings at baseline and follow-up appear in Table 1. Significant reduction was noted on all measures at all assessments. According to the Patients’ Global Impression of Improvement, three patients were “much/very much” improved at week 2, four at week 4, six at week 8, and eight at week 12. Although the scores showed a steady decline until week 12, treatment effect sizes began to reach clinically significant levels (one or more) by week 4.

Discussion

Our results are based on a small group, and the lack of control subjects precludes definitive conclusions on the effectiveness of earthquake simulator-assisted exposure treatment. The effect sizes at week 12, however, are comparable to those in a controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy of PTSD (7), which showed that exposure was superior to placebo (relaxation). Nevertheless, a controlled study is needed to verify these findings.

The potency of our treatment might in part be explained by exposure to a simulated unconditioned stimulus (i.e., earthquake tremors) and an opportunity to habituate to both the psychologically and physiologically aversive experience of shaking. In addition, relative to exposure to trauma reminders, this method may more effectively activate trauma-related fear and memories, a process that may be critical in the emotional processing of trauma (8). Furthermore, critical treatment parameters, such as the duration, grading, speed of exposure, and sense of control over tremors, could be more easily manipulated in our treatment.

Both the earthquake simulator and the treatment session were designed in ways to enhance the patients’ sense of control over their fear and other traumatic stress problems. The patients’ ability to control the earthquake simulator seemed to confer certain advantages. Gaining a sense of control over the tremors might have contributed to the reduction in the patients’ fear of earthquakes. In addition, the controllability element seemed to increase the patients’ motivation for and compliance during the treatment and helped them keep their anxiety within manageable limits. These treatment procedures seemed to contribute to the patients’ high satisfaction ratings.

The earthquake simulator-assisted treatment may also have a potential use in increasing psychological preparedness for earthquakes. Some anecdotal evidence suggests that habituation to tremors has a protective effect. For example, some sailors who reported minimal distress during the earthquakes attributed this to being used to the rocking and shaking sensations at sea. A successfully treated survivor stated that she did not rush out of her prefabricated house in a panic during an aftershock, as she used to do on similar occasions before treatment. Clearly, the resilience-building potential of earthquake simulator-assisted exposure deserves further study.

In conclusion, earthquake simulator-assisted exposure appears to be a promising behavioral intervention for earthquake survivors. It offers the possibility of an effective and cost-effective treatment for PTSD symptoms. It may be a useful adjunct to training programs designed to teach people how to protect themselves during earthquakes. Its fear-reducing effects may be useful in preventing debilitating panic during earthquakes so that people can practice their coping skills. Future controlled research needs to verify its usefulness in both the prevention and treatment of PTSD symptoms.

|

Received Nov. 1, 2001; revision received Aug. 6, 2002; accepted Dec. 2, 2002. From the Istanbul Center for Behavior Research and Therapy (Davranış Bilimleri Araştırma ve Tedavi Merkezi) as a project site of the Section of Trauma Studies, Divisíon of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, University of London. Address reprint requests to Dr. Başoğlu, Section of Trauma Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, 38 Carver Rd., London SE24 9LT, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Spunk Fund, Inc.

1. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP), version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

2. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM: A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist 1990; 13:187-188Google Scholar

3. Başoğlu M, Şalcıoğlu E, Livanou M, Özeren M, Aker T, Kılıç C, Mestçioğlu Ö: A study of the validity of a screening instrument for traumatic stress in earthquake survivors in Turkey. J Trauma Stress 2001; 14:491-509Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Beck AT, Rial WY, Rickels R: Short form of depression inventory: cross validation. Psychol Rep 1974; 34:1184-1186Medline, Google Scholar

5. Başoğlu M, Livanou M, Şalcıoğlu E, Kalender D: A brief behavioural treatment of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder in earthquake survivors: results from an open clinical trial. Psychol Med 2003; 33:1-8Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Marks IM: Principles of psychological treatment, in Fears, Phobias, and Rituals. New York, Oxford University Press, 1987, pp 458-494Google Scholar

7. Marks IM, Lovell K, Noshirvani H, Livanou M, Thrasher S: Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder by exposure and/or cognitive restructuring: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:317-325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Foa EB, Kozak MJ: Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull 1986; 99:20-35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar